Introduction

In the last few years, specialized academic genres have become a subject of scholarly interest in Mexico. Many publications have focused on the description of student genres in Spanish from the perspective of Systemic Functional-Linguistics (Castro Azuara & Sánchez Camargo, 2013; Ignatieva, 2014; Zamudio, 2016). Others have focused on student and expert genres written in L2 English (Englander, 2006; the studies in Perales-Escudero, 2010). Within this general line of inquiry, a few studies have also examined academic writing contrastively in English and Spanish. This research area is relevant because, as stated by García Landa (2006), English is an important language for Mexican academics to make their work known to an international audience.

Furthermore, it appears that there are important differences across scientific discourse in English and Spanish. On the one hand, Anglophone scientific prose has been characterized by high levels of rhetorical involvement and self-promotion by a number of empirical studies that have analyzed English scientific discourse across several disciplines (e.g. Hyland, 2000, 2005). On the other, Spanish-language scientific prose is held by some style manuals to be impersonal and objective (Regueiro Rodríguez & Sáez Rivera, 2013) despite some findings that suggest Spanish language papers in some disciplines tend to present results with greater confidence and commitment than English-language ones (Perales-Escudero & Swales, 2011). The picture therefore is not yet clear, and the contrast between the prescriptions of Spanish-language manuals and the findings of empirical studies suggests that further empirical research is warranted.

Against this backdrop, contrastive studies can shed light on the existence, nature, and extent of divergences in scientific prose across languages, and thus yield meaningful information for teachers of English for Academic Purposes (EAP) to better train learners to write in academic genres in English in a manner that meets the expectations of the international scientific community. This may in turn, increase the chances that their papers will be accepted, read, and even cited in high-impact journals. In addition, contrastive studies can contribute to translator training by providing trainers and trainees with valuable information about discipline-specific equivalences and differences across languages (Perales-Escudero & Swales, 2011).

Among Mexican contrastive studies, Crawford (2010) focuses on student essays and finds a trend for Mexican essays to be more convoluted than British ones, which he attributes to the values of Nahuatl rhetoric. Rodríguez-Vergara (2017) investigates variations in theme structure in a translated medicine article and finds differences related to the use of the reflexive passive se in Spanish and “we” in English. Contrastive studies focusing specifically on abstracts are Sandoval Cruz (2015) and (2016), which examined research article abstracts in applied linguistics and pharmacology, respectively. The author found differences in the abstracts’ move structures and degree of informativity: abstracts in international journals tend to include more moves and more information than abstracts in Mexican journals. Among the two moves that show strong differences are the gap move, and the results and discussion moves. Mexican publications tend to omit these two moves, perhaps because Mexican authors often assume readers’ knowledge of the problems, needs or lacunae that motivate their studies and, therefore, do not state in the abstract how their research meets them.

In that regard, Mexican abstracts in applied linguistics and pharmacology show similarities to abstracts written by Spanish nationals in other disciplines (Burgess & Martín-Martín 2010; Lorés, 2004; Lorés-Sanz, 2009; Martín-Martín, 2003) and to those written in other Romance languages, such as Italian (Bondi, 2016). Abstracts written in English overwhelmingly include both the gap move, and the results and discussion move. They also include other features, such as hedging (i.e., use of words that weaken or modulate claims) and boosting (i.e., use of words that strengthen claims), that are less common in abstracts in other languages. Bondi (2016) has attributed those differences to insufficient training in academic writing in countries where Romance languages are spoken, but also to a growing trend in English-language publications towards self-promotion due to scientists’ need to make their work stand out in today’s highly competitive knowledge market. Another factor that could explain these differences is the country of publication. Non-English publications often appear in national or regional journals. These are aimed at restricted, national audiences. In contrast, English-language publications are geared toward an international scientific audience, which is likely to hold papers to different discursive and rhetorical standards.

Focusing specifically on economics, a handful of studies have examined L1 economics discourse in a non-contrastive manner, as McCloskey (1998) did with English and Stagnaro (2015) and Martínez Serrano (2016) did with Spanish. Other studies (e.g. Sala, 2016; Bondi, 2016; Okamura & Shaw, 2016) have also focused on L1-English economics discourse but have sought to contrast it with that of other disciplines rather than other languages. Taken together, these studies paint a picture of economics as an interpretive discipline whose discourse in English maximizes efforts to appear inclusive and objective. This is achieved linguistically via the use of “we” to create a sense of reader involvement, and the use of impersonal expressions to frame knowledge (i.e., “this article found,” “the results show”). The discourse of economics in English also seeks to persuade readers with the use of modal verbs as hedges (e.g., “may”) and evaluative adjectives (e.g., “new”). For Spanish, the work of Martínez Serrano (2016) shows that economics discourse tries to appear objective via the use of nominalizations and passive and pseudo-passive constructions that hide individual agency. However, to the best of my knowledge, the discourse of economics in general, and of economics abstracts in particular, has not been investigated contrastively across English and Spanish. To address this gap, this study compares international, English-language economics research article abstracts (RAABs) with Mexican, Spanish-language economics RAABs.

According to Mexico’s National Council for Science and Technology (Consejo Nacional de Ciencia y Tecnología, Conacyt [2015]), economics is the Mexican scientific discipline with the strongest growth in number of international publications in the past few years. This is probably the result of Mexican economists’ growing awareness of the importance of publication in reputable international journals (Castañeda, 2015). However, Conacyt (2015) also shows that economics is one of the Mexican disciplines with the weakest international impact as measured by number of citations in international journals. While content quality surely exerts the strongest influence on a paper’s impact, the quality of the abstract may also play a role. This is because the abstract is usually the first contact between the paper and the reader. Therefore, it forms the basis upon which the reader may decide whether to read and/or cite the paper (Swales & Feak, 2009). Moreover, some potential readers often judge the quality of a paper by its abstract (Paul & Charney, 1995). It is therefore important for economists and translators to maximize the rhetorical force of English-language economics abstracts in order to increase the likelihood that Mexican economics papers will be read and cited. Applied linguistics can provide insights to guide the design of specialized EAP courses for students and professionals of economics and for translators as well.

In order to address this gap, this study compares international, English-language economics RAABs with English-language, Mexican economics RAABs (translated abstracts) and their Spanish-language source texts. The goals of the paper are to identify and describe areas of difference, and to derive pedagogical implications. It uses Systemic-Functional Linguistics (SFL) as its theoretical and interpretive background, and corpus linguistics methods to examine the corpora in focus. The following research questions are addressed:

- What areas of difference exist between translated Mexican economics abstracts and English-language international economics abstracts as determined by a corpus-linguistics keyword search?

- If any differences arise in the translated abstracts, are they also present in the source texts (i.e., a corpus of untranslated, Spanish-language Mexican economics abstracts)?

The findings point to differences in the interpersonal metafunction (the textual expression of readers’ and writers’ identities and their interaction), with international abstracts using a discrete set of interpersonal features and functions much more frequently than Mexican ones. Conversely, Mexican abstracts show higher frequencies of impersonal features. These differences point to divergent textualizations of the writer, the reader, and writer-reader interaction across the two corpora.

A few words on translation

One of the problems confronting translators of specialized genres concerns the differences in genres across cultural contexts. As decades of contrastive genre analysis have shown, there are real differences in the realization of genres across both national and disciplinary cultures. As stated by House (2006), these differences tend to be connected to the interpersonal metafunction of SFL. A translator can choose to adapt the source text to the cultural conventions and expectations of the target culture, or to preserve those of the source culture. According to Venuti (1995), the first type of translation may be called idiomatic or “domesticated,” whereas the second may be called “foreignized.” Following House (2006), the textual signals of writer-reader interaction may be one area where translators need to make these choices.

Writer-reader interaction: two Systemic-Functional views

At present, it is common to view academic written texts as part of an extended dialogue between the writer and readers within a target discourse community. A number of theoretical frameworks have attempted to capture the ways that such dialogue is textualized[1]in written language. This section presents two SFL perspectives on the issue: the engagement system (White, 2003; Martin & White, 2005) and the interpersonal management system (Thompson & Thetela. 1995).

The engagement system network is part of a broader framework, Appraisal Theory (Martin & White, 2005), which models evaluation within SFL. Engagement is inspired by the work of Russian literary theorist Mikhail Bakhtin. Among Bakhtin’s central insights is the realization that all written utterances respond to previous utterances of others. Some sentences make this fact more-or-less clear with their vocabulary and grammar. Others do not. I will exemplify this phenomenon with a passage from Ur (2009, 10):

In the classroom, it is the teacher’s job to promote these three learning processes by the use of appropriate teaching acts… This is not, of course, the only way people learn a language in the classroom. They may absorb new material unconsciously… Through such mediation, however, the teacher can provide a framework for organized, conscious learning.

From the Bakhtinian perspective of dialogic engagement, the second sentence is advanced as a response to a potential argument from a dissenting reader, namely that students learn even without teachers’ explicit promotion of the learning processes described by Ur. This is indicated by the use of “of course.” In Martin and White’s (2005) engagement system, this kind of sentence is labelled as an instance of CONCEDE (capital letters are used to follow SFL conventions that name different types of textual engagement). The following sentence extends this CONCEDE move by presenting one such argument, namely, that students “may absorb new material unconsciously.” The use of “may” is important here because it makes room for other opinions and possibilities (which other readers or the author may hold) instead of presenting the proposition as a fact. Therefore, this kind of sentence is said to ENTERTAIN the proposition instead of asserting it. The last sentence, beginning with “however,” is used by Ur to COUNTER the objections of dissenting readers that she just textualized.

These three sentences carry words that signal the presence of opinions or perspectives that are not the author’s. They are thus said to textualize the voices of the readers who would hold those perspectives. In SFL, they are called “heteroglossic utterances” and are said to be instances of heteroglossia, or the presence of multiple perspectives (i.e., the utterances of others) within an utterance. Heteroglossia is a word derived from the Greek words heteros (“distinct in kind”) and glossa (“tongue, language, speech”). It contrasts with monoglossia (from monos=one), which in the engagement system is the exclusion of other perspectives from an utterance. The first sentence in the excerpt above (“… it is the teacher’s job to promote these three learning processes…”) is monoglossic because none of its words acknowledges other perspectives. It simply asserts the author’s view as a truth. These monoglossic utterances are also called “bare assertions.”

Heteroglossic utterances can be contractive or expansive. Contractive ones seek to align the reader with the author’s positions and thus contract dialogic space. COUNTERS, or statements that oppose or rebut a previous statement, typically signaled with contrastive conjunctives such as but or however, are a kind of heteroglossic contractive option. By contrast, expansive utterances give the reader room to dissent with the author and thus expand dialogic space. One way that dialogic space is expanded is by calibrating the objectivity, truthfulness of generalizability of propositions with the use of modal verbs, epistemic verbs, and other resources (Martin & White, 2005). By using these resources, the authorial voice recognizes that alternative positions and interpretations are possible and/or acceptable. Then, propositions incorporating such recognition are said to be entertained, i.e., are considered instances of the systemic option ENTERTAIN.

Broadly speaking, heteroglossic options tend to construct a potentially dissenting reader that needs to be persuaded, whereas bare assertions construct a reader already convinced of the author’s positions. The use of bare assertions has been characterized as a disengaged style as no attempt is made to engage with skeptical, uninformed or dissenting readers (Pérez-Llantada, 2012; White, 2003).

While engagement is a valuable tool, it is not specifically concerned with writers’ explicit representations of themselves and readers in the text. Thompson and Thetela’s (1995) system of interpersonal management is a useful tool to explore such representation. This system models the linguistic resources used by writers to manage more-or-less explicit interactions with readers, as opposed to the management of the flow of information by text-structuring signals. One category of interpersonal management is the projection of roles, or the writer’s or reader’s presence in the text, with the use of, for example, personal pronouns, possessive adjectives, vocatives or group nouns. As stated by the authors (p. 108):

Projected roles are those which are assigned by the speaker/writer by means of the overt labelling of the two participants involved in the language event. The labelling is done by the choice of terms used to address or name the two participants and by the roles ascribed to them in the processes referred to in the clause. Projected roles depend on explicit reference in the text to the two participants: the speaker/writer can therefore choose not to project roles.

According to the authors, there is a cline from more to less visibility of the writer-reader presence that goes from vocatives to pronouns to possessives to group nouns. Vocatives provide maximal visibility. Group nouns such as company names decrease such visibility. Although Thompson and Thetela (1995) do not consider this feature (likely because their analysis is based on a corpus of advertisements), references to the text in sentences where the text itself is a subject or an object in the structure of the clause (e.g. “this paper presents…”) are another way in which the authorial presence is represented, albeit less visibly. Such references are clearly a way to label one of the participants in the language event: the writer(s). Thus, in this paper, they are considered to be authorial interpersonal projections at the least visible end of the cline. Other studies have combined interpersonal management with Appraisal (e.g. Lee, 2008). Together, the interpersonal management system and the engagement system provide a comprehensive way of examining discursive aspects of SFL’s interpersonal metafunction, or the way that language represents the interactants’ identities and roles.

Methods

This is a corpus-assisted study that combines the use of computerized tools with manual SFL analysis. The main type of automated analysis used was keyword search, which is explained below. The SFL analyses were grounded in the framework outlined above.

The corpora

This study compared three corpora: a corpus of Mexican Economics Abstracts in Spanish (hereafter MexEconSp), a corpus of translated Mexican Economics Abstracts in English (hereafter MexEconEng, containing exclusively the translated versions of the abstracts in MexEconSp), and a corpus of International Economics Abstracts in English (hereafter IntEconEng). MexEconEng is comprised of 163 abstracts and 18,575 words. MexEconSp contains 163 abstracts and 20,306 words. IntEconEng consists of 1,327 abstracts and 174,305 words. Each corpus contains all the abstracts from three different journals published between the years of 2010 and 2016.

The journals were chosen on the basis of three criteria: 1) they needed to be inclusive journals, accepting papers written from both orthodox and heterodox perspectives in economics; this is because adherence to these schools of thought within the discipline have been found to influence the move structure of abstracts in Spanish (Stagnaro, 2015) and may thus influence other discursive variables; 2) they needed to be indexed in the RePec database, which is one of the most prestigious and comprehensive in economics (Castañeda, 2015). The Mexican journals in the sample are Estudios Económicos, Economía: Teoría y Práctica, and Ensayos: Revista de Economía. The international, Anglophone journals are American Economic Review, Economic Inquiry and the Cambridge Journal of Economics. To apply criterion 1 above, I enlisted the help of a Mexican informant with a doctorate in economics who is a member of Mexico’s Sistema Nacional de Investigadores and who publishes in both Mexican and international journals. By following these two criteria for selection, I made sure that the two corpora would share a common set of features, or tertium comparationis (Connor & Moreno, 2005), so that the comparison would be valid. Having a tertium comparationis is one of the main criteria of validity in contrastive rhetoric studies such as this one.

Readers will notice that MexEconEng and MexEconSp are smaller corpora than IntEconEng. This is due to two simple facts: 1) fewer Mexican journals are included in RePec and, 2) the Mexican journals in MexEconEng publish fewer papers per issue and fewer issues per year than the international journals in IntEconEng. I could have decided to expand the size of MexEconEng by including more years. However, this would have affected the comparability of the corpora because of the possibility of diachronic language changes (Goh, 2011). One may also notice that variations in the size of the corpora to be compared are relatively unimportant in comparisons of specialized corpora consisting of texts written in the same genre (Flowerdew, 2004; Gabrielatos & Marchi, 2011, 2012; Goh, 2011). As stated by Sinclair (2001, xii) when discussing the use of small, specialized corpora: “comparison uncovers difference almost regardless of size.”

Procedures

Each online abstract was typed into an individual, plain text (.txt) file and named with a code consisting of the journal’s initials, the year of publication, a serial number, and the language of publication. My data analysis procedure combined corpus linguistics tools with SFL, an increasingly common approach in academic discourse studies. It is necessary to keep in mind that corpus linguistics is lexically driven (i.e., it focuses and depends on the presence of specific linguistic exponents), whereas SFL analysis is grammar- and function-driven (Hunston, 2012). Nonetheless, they are compatible and complementary if combined judiciously (Hunston, 2013; Thompson & Hunston, 2006). My approach was data-driven and similar to that of Lancaster (2014) and Bondi (2016). I started by analyzing inductively a randomly selected sample of 20 papers from each corpus. This analysis suggested that there were significant differences pertaining to writer-reader interaction, particularly along the lines of heterogloss and monogloss statements and explicit writer textualization.

Next, I sought to confirm or disconfirm these findings by using the concordance software AntConc (Anthony, 2011) to look for keywords across the two corpora. Keywords are words “whose frequency is unusually high in comparison with some norm” (Scott, 2008, 135). Keywords possess “keyness,” a property of some words that occur in one corpus much more often than they do in another one. It is not just frequency, but high frequency in one corpus in connection with low frequency in a reference corpus. Keyword search is a common starting point in corpus studies to identify quantitatively areas of maximal difference, and from there researchers can proceed to finer, more interpretive analyses (Hunston, 2012). The norm for comparison is usually that of a reference corpus, or a corpus that serves as a benchmark or point of comparison for a study corpus in order to know what words are distinctive in the study corpus (Baker, 1995). In this contrastive study, each corpus worked as both a study corpus and a reference corpus for its counterpart since it was my interest to know what distinguished one from the other. First I searched for keywords that would distinguish IntEconEng (i.e., words that are more common in this corpus) from MexEconEng. The resulting keywords (e.g. “may”, “we,” and “I”) appeared to confirm my initial analysis that certain heteroglossic and interactional features were much more common in IntEconEng than in MexEconEng.

However, because it could be the case that MexEconEng simply used different lexis to perform the engagement and interactional functions that appeared to vary from the results of the previous analysis, I conducted two additional procedures. I ran a second keyword search, this time with MexEconEng as the study corpus and IntEconEng as the reference corpus, and examined the keyword list looking for different words that would perform the same/similar functions (e.g. “could,” “us,” “the author”). Following Lancaster (2014), I also manually analyzed a randomly chosen sample comprising 20% of the papers of each corpus in order to a) further rule out the possibility that different lexis may be performing the discursive functions in focus, and b) determine whether the lexis in focus in MexEconEng was translated literally from MexEconSp. This last step was necessary in order to answer research question 2.

Results

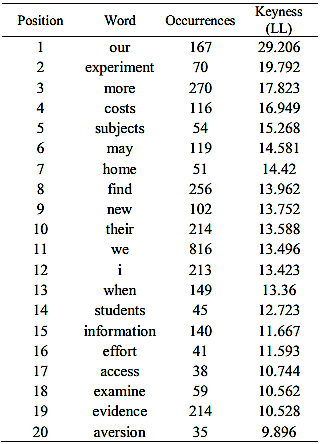

My first manual analysis suggested that engagement options, specifically ENTERTAIN, and writer projection with personal pronouns were more common in IntEconEng than in MexEconEng. This was confirmed by a keyword search with AntConc using IntEconEng as the study corpus and MexEconEng as the reference corpus. Table 1 presents the first twenty keywords yielded by AntConc, organized from the highest keyness value expressed as log-likelihood (LL). All these values are significant (p<.01) as LL values above 6.63 meet and exceed this cut-off point (Gabrielatos & Marchi, 2011, 2012).

Table 1. First twenty keywords in IntEconEng vs. MexEconEng.

As shown in Table 1, several of the words with higher keyness perform authorial projection (“our,” “we,” “I”). One of them, “may,” is a modal verb that works to present propositions as entertained and is thus dialogically expansive, which means that it gives readers room to disagree and thus textualizes a potentially skeptical or dissenting reader. Some examples of the use of these resources are below:

Example 1. However, we underpredict some of the correlation patterns; search frictions may play a role in explaining the discrepancy. (AER_2010_5)

Example 2. With this definition, additional questions arise as to who should appropriate the surplus or receive a portion of it. I contend that each, irrespective of their role in production, should have the capability to appropriate surplus (CJE_2015_23).

Example 3. Our results reveal that, on average, countries have adopted technologies 45 years after their invention. (AER_2010_53)

Example 4. The changes may cause long-run distortions in the economy, reducing long-term economic growth. (EI_2015_70).

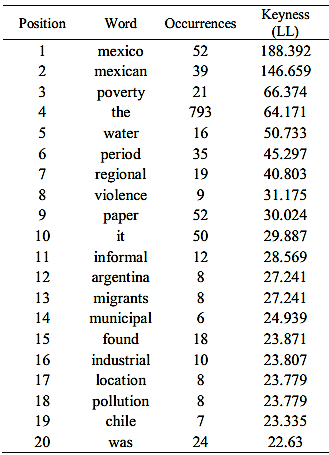

A search for keywords using MexEconEng as the study corpus and IntEconEng as the reference corpus showed that the words distinguishing the former from the latter are almost exclusively content words connected to the topics and geographical context of the abstracts (Table 2). The exceptions are words to refer to the paper: “paper” and “it.” The fact these are keywords further shows the impersonal nature of the abstracts in MexEconEng in contrast to the more personal nature of those in IntEconEng.

Table 2. First twenty keywords in MexEconEng vs. IntEconEng.

My manual search of the AntConc-generated keyword list for lexis performing authorial presence and heteroglossic entertainment yielded only one result: “could,” with 12 occurrences and a keyness value of 5.154. There were no personal pronouns, possessive adjectives or other references to the reader or the writer.

My manual examination of 20% of the abstracts in MexEconIng andMexEconSp (33 pairs of abstracts) somewhat confirmed the findings from the keyword search. Of all the papers in the sample, 22 (63.6%) were fully monoglossic, that is, all the clauses were presented as bare assertions. An example of a fully monoglossic abstract is below. Readers should note that this and all other examples are presented verbatim; no grammatical, lexical or punctuation infelicities were corrected.

Example 5a. This article discusses the economic reform of the People's Republic of China, adopting a historical perspective and considering the political and institutional factors that support it; special emphasis is placed in the dependence of export led growth on global processes, in terms of transfer of technology, investment and markets. In the second part, the focus is on macroeconomic imbalances caused by accelerated export development, exacerbated by changes in the global processes. As a conclusion some key changes in economic strategy are discussed and evaluated. [ETP_2016_3_ENG]

An examination of the source texts of these 22 translated abstracts showed that almost all the source texts were also fully monoglossic, as in Example 5b:

Example 5b. La reforma económica en la República Popular China es analizada desde una perspectiva histórica y considerando los factores político-institucionales que la sostienen; se hace hincapié en el rol crítico jugado por la economía global a través de la transferencia de tecnología, la inversión extranjera directa y la demanda externa. Se destacan, por otro lado, los desequilibrios macroeconómicos provocados por el acelerado desarrollo exportador y agudizados por el cambio de tendencia de los procesos globales. Como conclusión, se revisan y evalúan algunos cambios clave en la estrategia económica. (ETP_2016_03_SP) / This article discusses the economic reform of the People's Republic of China, adopting a historical perspective and considering the political and institutional factors that support it; special emphasis is placed in the dependence of export led growth on global processes, in terms of transfer of technology, investment and markets. In the second part, the focus is on macroeconomic imbalances caused by accelerated export development, exacerbated by changes in the global processes. As a conclusion some key changes in economic strategy are discussed and evaluated. (ETP_2016_3_ENG)

The one exception is shown in example 6 below. The comparison of the paired abstracts shows that a COUNTER clause in the source text (“sin embargo…” which means “however”) was translated as a prepositional phrase that is part of a bare assertion (“without finding…”).

Example 6. Moreover, the causal relationship between these two series is studied using a more robust Granger causality test, without finding any directional causality between them (ERE_2017_7_ ENG) / Además, la relación causal entre estas dos series es estudiada mediante una prueba más sólida que la de Granger, sin embargo, no encontramos ninguna dirección de causalidad entre las series. (ERE_2017_7_SP).

Of the remaining nine papers, four contained instances of ENTERTAIN, three of which used epistemic verbs (examples 7 and 8) and one of which included “could” with an ability meaning, which is not an ENTERTAIN but a bare assertion (example 9). The other five papers contained at least one COUNTER clause each (example 10). As seen from a comparison with the source texts in MexEconSp, these are literal translations that keep the same values of engagement as in the source text encoded with equivalent lexis.

Example 7. Results indicate that the general competitiveness effect is positive but not robust, given the considerable level of aggregation of the data used (ERE_2011_8_ENG) / Los resultados indican que el efecto del nivel general de competitividad es positivo pero no robusto, debido al nivel considerable de agregación de los datos utilizados (ERE_2011_8_SP).

Example 8. The results suggest that there was not capital mobility until 1982 (EE_2011_6_ENG) / Los resultados indican que no había movilidad del capital hasta 1982 (EE_2011_6_SP).

Example 9. It is presented a case study for the Laguna Metropolitan Area however the methodology could be applied to any other region. (ERE_2010_2_ENG) / La metodología se aplica al caso particular de la Zona Metropolitana de La Laguna, pero se puede aplicar en cualquier otra región (ERE_2010_2_SP).

Example 10. Second, migrants are younger and less female than suggested by the U.S. census, but older and more female than suggested by the Mexican census. (ERE_2013_5_ENG) / Segunda, los migrantes representan una mayor cantidad de jóvenes y una menor cantidad de mujeres, que lo sugerido por los datos de los Estados Unidos; pero son menos los adultos mayores y también más mujeres, que los sugeridos por el censo de México (ERE_2013_5_SP)

As for personal projection, five papers in MexEconEng included self-mentions with “we.” (examples 11 and 12). No instances of “I” were found in the sample.

Example 11. In addition, we propose a classification for ninis that could be used for the design of public policies (E_C_2015_6_ENG) / Asimismo, [este artículo] propone una clasificación de ninis para focalizar el diseño de políticas públicas.

Example 12. Methodologically we show that analysis of technology classes with network theory is a good tool for the analysis and determination of patent thicket (ETP_2014_4_ENG) / Metodológicamente, se muestra que analizar clases tecnológicas mediante la teoría de redes es un buen instrumento para el análisis y la determinación del fenómeno de patentes traslapadas (ETP_2014_4_ESP).

It is interesting that in these examples “we” is actually a divergence from the source texts. In those, either a reference to the text (“este artículo”) or the reflexive pseudopassive “se” was used. This was the case in another two of the manually analyzed papers. Only one of the papers used “we” as a literal translation of a Spanish verb inflected for the second person plural “nosotros”:

Example 13. We propose a critical analysis of the conception of the State in the evolutionary theory of Carlota Pérez [ETP_2012_10_ENG] / Proponemos un análisis crítico de la concepción del Estado en la teoría evolucionista de Carlota Pérez [ETP_2012_10_SP]

This data suggests that the translators of some of these abstracts were aware of the acceptability of “we” in English academic prose and chose to transpose the translated message by using this pronoun instead of carrying out a literal translation. Others, however, chose to preserve the least personal projection, which consists of references to the text. This was already apparent from the fact that “paper” is a keyword in MexEconIng (Table 2) and was confirmed by the manual analysis. There were twenty-one instances of authorial projection using “paper” (Examples 14 and 15). In fifteen cases, this was a literal translation of the Spanish words artículo or documento. In six cases, “paper” was used to translate the Spanish reflexive pseudopassive se (example 15). The remaining five of the 33 manually analyzed papers did not contain any authorial projections.

Example 14. This paper reviews the current status of the international fight against money laundering and the financing of terrorism (ETP_2016_1_ENG) / Este documento examina el estado actual de la lucha internacional contra el lavado de dinero y el financiamiento del terrorismo (ETP_2016_1_SP)

Example 15. Based on case study analysis this paper is an effort to identify the process by which firms are venturing into this Global Value Chain (ETP_2015_7_ENG) / Mediante estudios de caso se identifica el proceso mediante el cual las empresas de software se han podido insertar en la cadena de las TI (ETP_2015_7_SP).

Conclusions

This paper adds to a growing number of studies of the discourse of economics from a contrastive perspective. From the viewpoint of English, it confirms the findings of previous studies showing that the discourse of this discipline contains personal projections with “I” and “we” and opens dialogic space for dissenting readers by using ENTERTAIN options instead of bare assertions. This latter use has been characterized as heteroglossically engaged, deferential and respectful toward a questioning “disciplinary audience” (Pérez-Llantada, 2012, p. 103). It is valued by professional academic readers in Anglophone contexts (Thaiss & Zawacki, 2006).

By contrast, the data for Spanish show that the discourse of Mexican economics abstracts tends to be monoglossic. Most of the abstracts do not incorporate other perspectives in any way. Drawing on Pérez-Llantada (2012) and White (2003), this mode of expression can be characterized as a disengaged style, one that does not attempt to engage a questioning or dissenting reader. Further, the Mexican abstracts tend to refrain from the use of overt authorial projections and prefer the less visible one: references to the paper. In this regard, though, there is an important divergence between the source texts and the target texts. This difference is that the Spanish-language texts tend to be more impersonal. By contrast, the English-language texts are more personal. They bear the mark of the translators’ use of personalization strategies that render source-text references to the paper or passive constructions as “we” in the target texts.

In general, the findings show that the abstracts in MexEconEng incorporate some of the language use expected in the target culture context and preserve some of the conventions of the source culture that do match those of the target culture. In this case, the accommodation of target culture expectations appears to happen, albeit not extensively, in the area of personal projection. Several of the translators clearly chose to project the authors’ presence with “we” or the least visible option “paper” in places where the Spanish-language source text used se or the passive voice. This also shows that the Spanish-language abstracts are largely impersonal, which matches the description of Spanish academic style in Regueiro Rodríguez and Sáez Rivera (2013).

Such impersonality extends to the general absence of engagement resources in the Mexican abstracts in both languages. Thus, engagement is an area where the conventions of the source culture were preserved and there was no accommodation to the pragmatic expectations of the target culture. This absence of engagement in the source texts means that Mexican economists tend to write without attention to a skeptical or dissenting audience. Perhaps they prefer to let the rigor of their methods speak for itself, and thus use a rhetoric of justification rather than one of persuasion. A rhetoric of justification relies on methodological soundness as a source of rhetorical force, whereas a rhetoric of persuasion uses discursive devices to achieve rhetorical effects (Jiménez-Aleixandre & Erdurán, 2008). Clearly, English-speaking economists deploy both kinds of rhetoric, whereas Spanish-speaking economists and translators tend to rely more on a rhetoric of justification and make little use of a rhetoric of persuasion.

We cannot conclude that the low rates of citation of Mexican economics papers are a result of the rhetorical and discursive differences outlined above. Nevertheless, their potential impact cannot be ruled out in light of findings suggesting that some Anglophone readers react to the discursive devices and organization of abstracts when deciding what papers to read in full (Paul & Charney, 1995). Therefore, it would be advisable to design and implement EAP curricula with the goal of teaching authors and translators about the discursive conventions expected in international, English-language publications. Indeed, lack of training in writing has been suggested as one of the causes of the limited engagement with readers found in abstracts in other languages. It may well be the case that the absence of adaptation to international engagement practices in the translated abstracts is not due to a conscious decision, but to insufficient knowledge and skill on the part of the translators. This possibility deserves further exploration.

Some limitations of this paper include the lack of manual analysis of engagement patterns in all three corpora. Although manual engagement analysis of a limited sample is acceptable in combination with automated analyses of the whole (Lancaster, 2014), an engagement analysis of the whole corpus might yield somewhat different results. Nevertheless, the finding that Mexican economics abstracts are predominantly monoglossic is consistent with the findings of other studies of Mexican academic prose (Zamudio Jasso, 2017; Valerdi Zárate, 2014), a fact which lends credibility to the results of this paper. However, future studies should explore this issue and the possible impact of teaching interventions on the use of engagement resources by Mexican academic writers. Moreover, future studies should also explore other areas of difference revealed by the keyword analysis, such as the higher frequency of past tense verbs (e.g. “found” vs. “find”) in MexEconEng. The presence of grammatical errors in the translations, which I have presented in the examples but not discussed, is also an area that merits further attention.

References

Anthony, L. (2011). AntConc (Version 3.2.2) [Computer Software]. Tokyo, Japan: Waseda University. Available from http://www.antlab.sci.waseda.ac.jp/

Baker, M. (1995). Corpora in translation Studies. An overview and suggestions for future research. Target Online, 7(2). 223-243. doi: 10.1075/target.7.2.03bak

Bondi, M. (2016). Changing voices: authorial voice in abstracts. In M. Bondi & R. Lorés-Sanz (Eds.), Abstracts in academic discourse: Variation and change (pp. 243-270). Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang.

Burgess, S., Martín-Martín, P. (2010). Interpersonal features of Spanish social sciences journal abstracts: A diachronic study. In R. Lorés-Sanz, P. Mur-Dueñas & E. Lafuente-Millán (Eds.), Constructing interpersonality: Multiple perspectives on written academic genres (pp. 99-115). Newcastle, UK: Cambridge Scholars Publishing.

Castañeda, G. (2015). ¿Se encuentra la ciencia económica en México en la vanguardia de la corriente dominante? El Trimestre Económico, 326, 433-483. Retrieved from: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=31342333007

Castro Azuara, M. & Sánchez Camargo, M. (2013). La expresión de opinión en textos académicos escritos por estudiantes universitarios. Revista Mexicana de Investigación Educativa, 18(57), 403-426. Retrieved from: http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=14025774008

Conacyt. (2015). Informe general sobre el estado de la ciencia, la tecnología y la innovación. México, D.F.: Conacyt. Retrieved from http://www.siicyt.gob.mx/index.php/transparencia/informes-conacyt/informe-general-del-estado-de-la-ciencia-tecnologia-e-innovacion/informe-general-2015/3814-informe-general-2015/file

Connor, U. & Moreno, A. (2005). Tertium comparationis: A vital component in contrastive rhetoric research. In P. Bruthiaux, D. Atkinson, W. G. Eggington, W. Grabe & V. Ramanathan (Eds.), Directions in applied linguistics: Essays in honor of Robert B. Kaplan (pp. 153-164). Clevendon, UK/Buffalo. NY/Toronto, Canada: Multilingual Matters.

Crawford, T. (2010). The cultural rhetoric of second language writing. In S. Santos (Ed.), EFL writing in Mexican universities: Research and experience (pp. 55-74). Tepic, Nayarit, Mexico: Universidad Autónoma de Nayarit.

Englander, K. (2006). Revision of scientific manuscripts by nonnative English-speaking scientists in response to journal editors’ language critiques. Journal of Applied Linguistics, 3(2), 129-161. doi : 10.1558/japl.v3i2.129

Flowerdew, L. (2004). The argument for using English specialized corpora to understand academic and professional language. In U. Connor & T. A. Upton (Eds.), Discourse in the professions: Perspectives from corpus linguistics (pp. 10-33). New York, NY and London, UK: Continuum.

Gabrielatos, C. & Marchi, A. (2011). Keyness: Matching metrics to definitions. Theoretical-methodological challenges in corpus approaches to discourse studies - and some ways of addressing them. University of Portsmouth, 5 November 2011. Retrieved from http://eprints.lancs.ac.uk/51449

Gabrielatos, C. & Marchi, A. (2012). Keyness: Appropriate metrics and practical issues. CADS International Conference, Bologna, Italy, 13-15 September 2012. Retrieved from http://repository.edgehill.ac.uk/4196

García Landa, L. G. (2006). Academic language barriers and language freedom. Current Issues in Language Planning, 7, 61-81. doi: 10.2167/cilp084.0.

Goh, G. Y. (2011). Choosing a reference corpus for keyword calculation. Linguistic Research, 28(1), 239-256. Retrieved from http://210.101.116.28/W_files/kiss10/82800375_pv.pdf

House J. (2006). Text and context in translation. Journal of Pragmatics, 38, 338-358. doi: 10.1016 / j.pragma.2005.06.021

Hunston, S. (2012). Afterword. In K. Hyland, C. M. Huat & M. Hartford (Eds.), Corpus applications in applied linguistics, pp. 242-248. London, UK and New York. NY: Continuum.

Hunston, S. (2013). Systemic functional linguistics, corpus linguistics and the ideology of science. Text & Talk, 33(4-5), 617-640. doi: 10.1515/text-2013-0028

Ignatieva, N. (2014). Participantes y proyección en los procesos verbales en español: un análisis sistémico de géneros académicos estudiantiles. Onomázein, número especial IX ALSFAL, 8-20. doi: 10.7764/onomazein.alsfal.7

Jiménez-Aleixandre, M. P., Erdurán, S. (2008). Argumentation in science education: An overview. In S. Erdurán & M. P. Jiménez-Aleixandre (Eds.). Argumentation in science education: Perspectives from classroom-based research. (pp.3–29). Dordrecht: Springer.

Lancaster, Z. (2014). Exploring valued patterns of stance in upper-level student writing in the disciplines. Written Communication, 31(1), 27-57. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/0741088313515170

Lee, S. H. (2008). An integrative framework for the analyses of argumentative/persuasive essays from an interpersonal perspective. Text & Talk, 28(2), 239-270. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/TEXT.2008.011

Lorés, R. (2004). On RA abstracts: From rhetorical structure to thematic organization. English for Specific Purposes, 23(3), 25-43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2003.06.001

Lorés-Sanz, R. (2009). Different worlds, different audiences: A contrastive analysis of research article abstracts. In E. Suomela-Salmi & F. Dervin (eds.), Cross-linguistic and Cross-cultural Perspectives on Academic Discourse (pp. 187-198). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins.

McCloskey, D. N. (1998). The rhetoric of economics. Madison, WI: University of Wisconsin Press.

Martín-Martín, P. (2003). A genre analysis of English and Spanish research paper abstracts in experimental social sciences. English for Specific Purposes, 22(1) 25-43. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-4906(01)00033-3.

Martin, J. R. & White, P. R .R. (2005). The language of evaluation: Appraisal systems in English. New York, NY, and London, UK: Continuum.

Martínez Serrano, V. (2016). Una aproximación al discurso económico en textos periodísticos. In N. Ignatieva & D. Rodríguez Vergara (Eds.), Lingüística sistémico-funcional en México: aplicaciones e implicaciones (pp. 79-96). Ciudad de México, México: UNAM.

Okamura. A. & Shaw, P. (2016). Development of academic journal abstracts in relation to the demands of stakeholders. In M. Bondi & R. Lorés-Sanz (Eds.), Abstracts in academic discourse: Variation and change (pp. 287-318). Bern, Switzerland: Peter Lang.

Paul, D. & Charney, D. (1995). Introducing chaos (theory) into science and engineering: effects of rhetorical strategies on scientific readers. Written Communication 12(4), 396-438. doi: 10.1177/0741088395012004002

Perales-Escudero, M. D. (Ed.) (2010). Literacy in Mexican higher education: Texts and contexts. Puebla, México: Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla.

Perales-Escudero, M. D. & Swales, J. M. (2011). Tracing convergence and divergence in pairs of Spanish and English research article abstracts: The case of Ibérica. Ibérica: Revista de la Asociación Europea de Lenguas con Fines Específicos.21, 49-70. Retrieved from http://www.redalyc.org/articulo.oa?id=287023883004

Pérez-Llantada, C. (2012). Scientific discourse and the rhetoric of globalization: The impact of culture and language. London, UK, and New York, NY: Continuum.

Regueiro Rodríguez, M. L. & Sáez Rivera, D. M. (2013). El español académico. Guía práctica para la elaboración de textos académicos. Madrid, Spain: Arco/Libros.

Rodríguez-Vergara, D. (2017). A systemic-functional approach to the passive voice in English-into-Spanish translation: Thematic development in a medical research article. Open Linguistics, 3, 1-17. doi: 10.1515/opli-2017-0001

Sala, M. (2016). Research article abstracts as domain-specific epistemological indicators. A corpus-based Study. In M. Bondi & R. Lorés-Sanz (Eds.), Abstracts in academic discourse: Variation and change (pp. 243-270). Bern. Switzerland: Peter Lang.

Sandoval Cruz, R. I. (2015). Análisis contrastivo de movimientos retóricos en resúmenes de lingüística aplicada escritos en español mexicano e inglés norteamericano. In M. D. Perales Escudero & M. G. Méndez López (Eds.), Experiencias de docencia e investigación en lenguas modernas (pp. 20-31). Chetumal, México: Universidad de Quintana Roo.

Sandoval Cruz, R.I. (2016). A comparative analysis of research article abstracts in medicine: Implications for teaching. In M. C. G. Márquez Palazuelos, D. G. Toledo Sarracino & L. G. Márquez Escudero (Eds.), Experiencias en lenguas e investigación del siglo XXI (pp. 414-425). Mexicali: Universidad Autónoma de Baja California.

Scott, M. 2008. Oxford Wordsmith Tools 5.0. Liverpool, UK: Lexical Analysis Software.

Sinclair, J. Mch. (2001). Preface to Small corpus studies in ELT. In M. Ghadessy, A. Henry and R. Roseberry (Eds.), Small corpus studies in ELT (pp. vii-xv). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: John Benjamins.

Stagnaro, D. (2015). Configuraciones retórico-lingüísticas del resumen en artículos científicos de economía: Contrastes en el interior de la disciplina. Revista Signos. Estudios de Lingüística, 48(89), 425-444. doi: 10.4067/S0718-09342015000300007.

Swales, J. M. & Feak, C. B. (2009). Abstracts and the writing of abstracts. Ann Arbor, MI: The University of Michigan Press.

Thaiss, C. & Zawacki, T. (2006). Engaged writers and dynamic disciplines: Research on the academic writing life. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook Publishers.

Thompson. G. & Thetela, P. (1995). The sound of one hand clapping: The management of interaction in written discourse. Text & Talk, 15(1), 103-127. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/text.1.1995.15.1.103

Ur, P. (1991). A course in language teaching: Practice and theory. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Venuti, L. (1995). The Translator‘s Invisibility: A History of Translation. London, UK, and New York, NY: Routledge.

White, P.R.R. (2003). Beyond modality and hedging: a dialogic view of the language of intersubjective stance. Text & Talk, 23(2). 259-284. doi: https://doi.org/10.1515/text.2003.011

Zamudio, V. (2016). La expresión de opiniones y puntos de vista en textos académicos estudiantiles sobre literatura. Lenguaje, 44(1), 35-59. Retrieved from http://historiayespacio.univalle.edu.co/index.php/lenguaje/article/view/4629/6845

Zamudio Jasso, V. (2017). El estudiante ante el texto: caracterización de los recursos de posicionamiento del estudiante-escritor (Doctoral dissertation). Unpublished doctoral dissertation. UNAM, Mexico City.

Valerdi Zárate, J. (2014). La dimensión interpersonal del lenguaje académico en inglés como L2: análisis de la expresión de ACTITUD y COMPROMISO en el ensayo universitario sobre literatura (Unpublished master’s degree thesis). UNAM, Mexico City.

[1] “Textualize” is used a verb in SFL and other texts linguistics traditions. It highlights two facts: 1) not all writing is text, some is just isolated words; meaning that is textualized is made coherent with other meanings within a unity, 2) meaning pre-exists texts and individual meanings becomes textualized through a process of selection and integration with other meanings and with grammatical and lexical forms.