Introduction

Research interest in the use of strategies by students was prominent in the 1970s when ‘good language learners’ studies identified characteristics inherent to successful language learners (Naiman, Frohlich, Stern & Todesco 1978; Rubin 1975; Stern 1975). These studies generated interest in exploring the successful strategies that these ‘good’ learners use in their language learning process. This information is beneficial for less successful learners so that they may be able to use these successful strategies in their learning process.

Although the study of strategies has received much attention in recent decades, there have been few studies on this topic carried out in the Mexican context. A group of researchers from the Universidad de Quintana Roo (UQROO) conducted research in 2006, in which students from the BA in ELT in Chetumal were trained in the use of selected strategies in the four skills according to their level of language proficiency. The results were positive and students expressed the need for this kind of training in an open questionnaire given at the end of the workshops provided for these students (see Méndez & Marín 2007).

Consequently, the research team at UQROO decided to further explore which strategies were currently used by students in BAs in ELT in other Mexican public universities. UQROO also wanted to develop a framework for future strategy training in their BA ELT. In order to validate this framework it was important to know what strategies were used by BA ELT students in other public universities. Students from five public universities were interviewed in order to find out which strategies were used and at which proficiency levels they were using these strategies.

This article will report on the study conducted in the following Mexican universities which offer degree programs in ELT: Universidad Autónoma de Yucatán (UADY), Universidad Autónoma del Estado de México (UAEM), Universidad Autónoma del Carmen (UNACAR), Universidad Autónoma de Chiapas (UNACH), and Universidad Veracruzana (UV). These five universities were selected for this small scale project because of their geographical location in the southeast of Mexico. The students from the above universities were interviewed at the end of 2007, in order to find out what strategies in the four skills they used for their language learning. In this article I will only report on the strategies used for speaking in the five universities. It should be mentioned that the original study carried out by QROO (see Appendix 1) was used as a basis to design the questionnaire for the five universities.

Language Learning Strategies

Strategy research has led to a distinction between strategies employed for different purposes such as communication, performing in the language, retrieving information and the processes of speaking, listening, reading and writing, to name only a few. Cohen (1998) categorises strategies into two areas: those for the use of language, and those for learning the language:

Second language learning strategies encompass both second language learning and second language use strategies. Taken together they constitute the steps or actions consciously selected by learners either to improve the learning, the use of it or both. (p. 5)

A number of studies (O’Malley & Chamot 1990; Oxford 1990: Rubin 1981) led to the introduction and development of diverse taxonomies. Rubin’s research (1981) includes the following categories of strategies: clarification/verification, guessing/inductive inferencing, deductive reasoning, practice, memorization and monitoring. O’Malley and Chamot (1990) divide strategies into three dimensions: metacognitive strategies, cognitive strategies and social-affective strategies. Oxford (1990) developed a taxonomy that divides strategies into direct and indirect strategies: direct strategies are those “that directly involve the target language” (p. 37), while indirect strategies “provide indirect support for language learning through focusing, planning, evaluating, seeking opportunities, controlling anxiety, increasing cooperation and empathy and other means” (p. 151). Direct strategies include memory, cognitive and compensation strategies, and indirect strategies include metacognitive, affective and social strategies.

According to Tudor (1996), an area of strategy research which has attracted a great deal of attention is learner training. It is defined as the following:

the process by which learners are helped to deepen their understanding of the nature of language learning, and to acquire the knowledge and skills they need in order to pursue their learning goals in an informed and self-directive manner. (p.37)

Learner training has been of interest to language teachers because it can be applied to different situations and contexts in the ELT world. Thus, a range of books to help students acquire language learning strategies has been published (see Ellis & Sinclair, 1989; O’Malley & Chamot 1990; Oxford 1990). Studies from a number of countries have reported a significant increase in the use of strategies by students, as well as an improvement in their language proficiency (see Chen 2007; Issitt 2008; Méndez & Marín 2007).

Speaking Strategies

An important component of language learning strategy training is that of speaking strategies. Oral strategies are referred to in the literature as communicative strategies, communication strategies, conversation skills or oral communication strategies; for the purpose of this article speaking strategies are those devices used by students to solve any communication problem when speaking in English. According to O’Malley and Chamot (1990), speaking strategies are crucial because they help foreign language learners “in negotiating meaning where either linguistic structures or sociolinguistic rules are not shared between a second language learner and a speaker of the target language” (p.43).

One goal of a language learner may be to speak the foreign language in different oral exchanges and ultimately to be a competent speaker. For Hedge (2000), a competent speaker knows how to make use of speaking strategies. Hedge (ibid) comments that: “These strategies come into play when learners are unable to express what they want to say because they lack the resources to do so successfully” (p. 52). These verbal and non-verbal strategies (e.g. verbal circumlocution, clarification, non-verbal mimicry, gestures, etc.) may be used to compensate for a breakdown in communication or for unknown words or topics, and they may also be used to enhance effective communication.

Speaking strategies are essential, since they provide foreign language learners with valuable tools to communicate in the target language in diverse situations. However, there is disagreement as to whether or not to teach speaking strategies. Kellerman (1991) advocates against such training and believes that learners can transfer these strategies naturally from their native language to the target language. On the other hand, Canale (1983) encourages training in speaking strategies because:

learners must be shown how such a strategy can be implemented in the second language... Furthermore, learners must be encouraged to use such strategies (rather than remain silent...) and must be given the opportunity to use them. (p.11)

It is my belief that students should be given this kind of training in language classes because they do not necessarily transfer L1 (first language) skills to the L2 (second language). In a previous study (Méndez 2007), I argue that learners tend to remain silent or rely on the teacher to compensate for unknown vocabulary or grammar structures. In this same study, when ten learners were audio-recorded performing speaking tasks before training, only two made use of a speaking strategy, thus indicating that learners may not always transfer L1 knowledge to L2. A study carried out in the Mexican context by Mugford (2007) reveals that learners and even teachers are not prepared to deal with some not-so-pleasant communicative exchanges, including rudeness, disrespect, and impoliteness. Although this could be considered an unrelated topic, Mugford argues that students should be taught speaking strategies so that they may be able to communicate realistically when interacting in English.

In a recent study Nakatani (2005) showed that students who were taught speaking strategies made a significant improvement in their oral tests. The teaching of speaking strategies could complement teaching a foreign language and ELT training; however, in practice it seems that the teaching of speaking strategies may not be given enough importance. In order to support my argument, I will now analyze three research studies in the area of speaking strategies in different ELT contexts; all present positive results.

Three Studies on Speaking Strategies

The first study that I will present was carried out by Issitt (2008) in a UK university during a ten-week pre-semester program of English for academic purposes, which prepared students for the speaking test of the International English Language Testing System (IELTS). This preparation consisted of three aspects: 1) developing students’ confidence with an emphasis on reducing exam anxiety and on offering exam practice, 2) providing students with the IELTS regulations so as to better inform the students as to what the speaking test was about, and 3) making students aware of the marking of the IELTS exam criteria and helping them to adjust their speaking performance to match these criteria. In this course 35 students participated; however only 13 took the IELTS exam because the other 22 had already entered their respective university departments. The results showed that the training of these students in strategic performance aided them in passing the test with the required scores for university entrance. Although the sample was small, the preparation of students in the use of strategies made them better prepared to tackle tasks in foreign language learning. According to Issitt (2008), “Encouraging students to use a variety of perspectives may also help motivate them to study independently and to consider different theoretical positions” (p. 136). This aspect of learner training is important, because one of the desired goals of education is to help learners to think critically so that they are in charge of their learning process. Learner training allows students to transfer these strategies to other aspects of the learning process.

The second study analyzed was carried out by Mugford (2007), who interviewed 84 EFL (English as a Foreign Language) users in Mexico in order to identify impolite interactional situations experienced by Mexican students and teachers. Mugford (2007) argues that rudeness is a part of everyday language usage and should be included in language classes in order to prepare learners to interact in impolite situations. Due to the results of the study, Mugford argues for the inclusion of activities to prepare students to deal with this type of communicative exchange. Although he does not specifically refer to these practices as speaking strategies, he does advocate strategy training as a tool to better prepare learners for real life speaking exchanges.

The third study was conducted by Gallagher-Brett (2007), who applied a questionnaire to elicit information concerning learners’ beliefs aboutspeaking a foreign language. The students surveyed were in their final year at a secondary school in South East England, and were learning German. The questionnaire consisted of statements with a rating scale from one to five (one is 'strongly disagree' and five is 'strongly agree'). Students had to identify to what extent they agreed or disagreed with the statements. Students were also asked to answer open-ended questions in order to find out the strategies used while speaking in the foreign language. According to Gallagher-Brett (2007), the three strategies used most by students were practicing, revising, and repetition at home after revision. Although the results were from a very small number of participants, they reveal that the participants used strategies when speaking a foreign language. An interesting feature of the findings was the acknowledgement by students of failure due to individual factors related to their actions, efforts and feelings. This refers to the participants’ awareness of themselves as learners and of their responsibility for their own learning actions and outcomes. The two main themes emerging from this study are: awareness of strategy use by students, and the role of affective factors such as confidence, mood and anxiety when speaking a foreign language.

The students stated that practice and revision are the most important activities conducive to successful speaking of a foreign language. These two strategies are metacognitive and although they are important, my main argument in this article is the need to train students in the use of speaking strategies to help them better their performance when interacting in English.

Purpose of the Study

In order to find out which speaking strategies were being used by BA ELT students in the five Mexican universities, the following research questions were formulated:

1. Which speaking strategies are most used by UQROO BA ELT students?

2. Which speaking strategies are used by BA ELT students in five Mexican universities to overcome problems when speaking in English?

First Stage of the Study

This study consisted of two main stages. In the first stage, students from UQROO answered an open-ended questionnaire (see Appendix 1) concerning the strategies they used when facing four specific constraints while speaking in English:

-unknown vocabulary or structures,

-words or phrases not heard clearly,

-taking time to think, and

-not understanding the received message.

This questionnaire was answered by 142 students (88 beginners, 36 intermediate, 18 advanced students). In addition, the students’ teachers were asked to complete a checklist of the strategies they observed their students use while speaking in their English classroom. The checklist was based on Dörnyei and Scott’s (1995) classification of communication strategies into direct, interactional and indirect strategies. Due to limited space in this article, this checklist is not included. Next, a series of structured observations were carried out to allow the researcher to corroborate reports from the students and teachers.

The students’ questionnaires revealed 162 speaking strategies, which were then categorised and contrasted with the results of the teachers’ checklists and the researcher’s observations. Finally, the 162 strategies were collapsed into a set of 20, as many of the strategies overlapped. After more in-depth analysis and discussion among the five researchers from UQROO, those strategies were collapsed into the following 14 speaking strategies:

1. If I do not know how to say a word or phrase, I ask a classmate or my teacher.

2. I use the dictionary to prepare a role play or communicative activity in class.

3. If I do not know how to say a word, I use a synonym or describe what I want to say.

4. If I do not know how to say a word in English, I say it in Spanish.

5. If I do not know how to say a word or phrase, I use gestures and my hands.

6. I ask my speaking partner to repeat a word or phrase if I do not hear it clearly.

7. If I do not hear a word or phrase clearly, I relate it to the part of the conversation that I understood.

8. I use known words and phrases when I do not know how to say something.

9. I structure some ideas in my mind before speaking.

10. To gain time, I use fillers such as: and, well, etc.

11. I repeat the last word or phrase I said to gain time.

12. I do not think too much before speaking so that ideas can flow in English.

13. I ask my speaking partner to repeat or explain in different words what I did not understand.

14. I tell my speaking partner when I do not understand something.

These 14 strategies were eventually included in the Strategy Language Learning Questionnaire (SLLQ; see Appendix 2).

The UQROO research team developed the SLLQ after the results of the first stage of the study were analysed. For the second stage, the SLLQ was appliedto explore the use of the learning strategies among the students of the five participating institutions. This SLLQ consisted of five sections: listening, speaking, reading, writing and vocabulary. Each section asked students to report their strategy use using a four-point Likert scale: 1) ‘almost never’, 2) ‘sometimes’, 3) ‘quite frequently’, and 4) ‘almost always’. The items in the SLLQ were those that students at UQROO reported using the most in the first stage of the study. This article reports only the findings of the use of speaking strategies. Information regarding the other abilities is therefore not included.

Preliminary Results of the UQROO Students

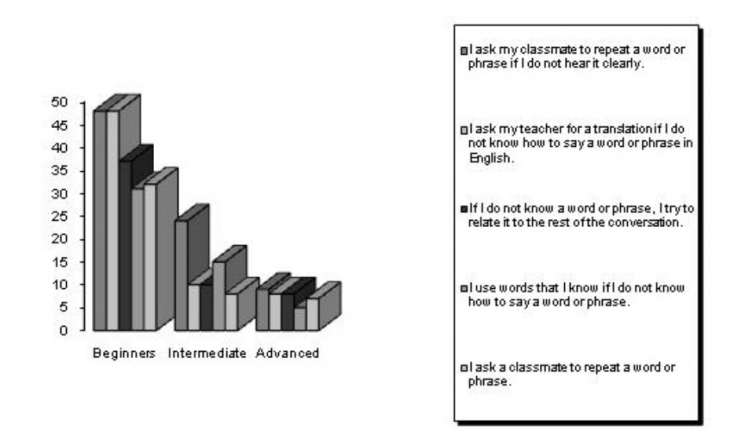

The first research question, which focused on finding out which speaking strategies were used by the UQROO students, yielded the 14 strategies above. This indicates that students were aware of speaking strategies and made use of them when interacting in English. Of the 14 strategies that UQROO students reported using, the five that they used the most are shown in Figure 1:

Figure 1: Speaking strategies most used by UQROO BA ELT students

Beginners stated resorting to their classmates for unknown vocabulary or structures. Although beginner students reported using all five strategies shown in Figure 1, their use was different from that of intermediate and advanced students. This is understandable, because beginner students have just started learning the language. Intermediate students reported the most varied use of strategies, and again this can be understood in terms of their level of proficiency, since they are in the process of acquiring more vocabulary and using more structures in their daily classes. Advanced students reported strategy use that was more complex than that of the other two groups. Advanced learners are more confident; they are already in the final stages of their degree programs, and they use strategies such as asking for repetition and clarification. Beginners and intermediate students choose to rely on their teachers, classmates and dictionaries for help when communicating in English. These preliminary results were encouraging, as they showed that students were making use of strategies on their own without any previous strategy training.

Second Stage of the Study

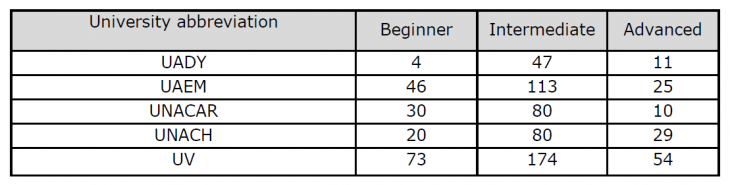

The second stage was the application of the Strategy Language Learning Questionnaire to the students in the other five participating universities. One researcher from UQROO was in charge of giving out the questionnaire to students in each of the five universities. A total of 796 students answered the SLLQ: 221 were identified as male, 570 as female and five did not answer the question on gender. Ages ranged from 17 to 54, and students were divided into three different levels: beginner, intermediate and advanced. The following is a breakdown of the levels and universities:

Table 1: The five universities and student levels

Students were asked how often they used the strategies using the same four-point Likert scale. The results obtained from this collection procedure were entered into a SPSS database (Statistical Package for the Social Sciences) for analysis.

Results of Stage Two

In order to explore the patterns of strategy used by students from the five universities in the second stage of the research, the 14 strategies included in the SLLQ will be presented individually, beginning with the highest percentages of use on the Likert scale.

Speaking Strategy 1: If I do not know how to say a word or phrase, I ask a classmate or my teacher.

The results show that this strategy is widely used by students in the five universities. The highest percentage of reported use of this strategy was found at the ‘almost always’' point of the scale in all the three levels. A percentage of 54.9 of beginner students ‘almost always’ used this strategy, while for intermediate students it was 46.2%. It is understandable that the lowest percentage of use was among the advanced students (36.4%), because they should already have a solid command of the language. Beginner students make more use of this strategy because they are in the process of acquiring new language. Thus their level of proficiency could influence their use of this strategy, since they are not as confident in the use of the language as those students at other levels of proficiency.

Speaking Strategy 2: I use the dictionary to prepare a role play or communicative activity in class.

This strategy is ‘almost always’ used by 43.1% of beginner students. Although it may seem unusual to use a dictionary in a speaking activity, this strategy refers to classroom activities in which the students have time to use their dictionaries. A percentage of 32.8 of intermediate students ‘almost always’ use this strategy. The lowest percentage of use of this strategyis tobefound among advanced students, 16.3% of whom use this strategy ‘sometimes’. Again, their level of proficiency may influence their use of this strategy, as advanced students are less likely to be in need of a dictionary since they already have a good grasp of the language.

Speaking Strategy 3: If I do not know how to say a word, I use a synonym or describe what I want to say.

This strategy is used ‘almost always’ by 68.0% of advanced students, which indicates that it is in constant use. This strategy represents a tool which students can employ in order to maintain the flow of communication and to compensate for lack of knowledge. Although the highest percentage of use is among advanced students, 49.8% of intermediate students also reported using this strategy ‘almost always’. Beginner students also make use of this strategy but at a lower rate, with 36.6% using it ‘quite frequently’.

Speaking Strategy 4: If I do not know how to say a word in English, I say it in Spanish.

In general, students did not consider this strategy useful, since they only reported using this strategy ‘sometimes’. Percentages of 36.6 of beginner students and 35.3 of intermediate students used this strategy ‘sometimes’, as they may consider that it is important at this stage of their learning process not to resort to Spanish. Advanced students reported the highest percentage of 'almost never' use of this strategy, at 40.3%. Advanced students might not use this strategy much because they already have a good command of the language, while beginner and intermediate students may be inhibited by teachers’ rules on language use in the classroom. Perhaps students should be aware of this strategy as a tool to use in order to keep the flow of interaction when speaking in English.

Speaking Strategy 5: If I do not know how to say a word or phrase, I use gestures and my hands.

Students use this strategy ‘quite frequently’ at all three levels. Advanced students reported the highest percentage of use, with 37.2% indicating that they use it to compensate for unknown vocabulary. Percentages of 35.6 of intermediate students, and 34 of beginner students also use this strategy ‘quite frequently’, which indicates that students consider this strategy a useful one.

Speaking Strategy 6: I ask my speaking partner to repeat a word or phrase if I do not hear it clearly.

A percentage of 51.2 of advanced students stated using this strategy 'almost always' when interacting in English. In general it seems that this strategy is a resource that students of all three levels use when they do not clearly understand words or phrases. Percentages of 50.7 of intermediate students and 49.7 of beginner students reported the use of this strategy with ‘almost always’. As we can see, all three levels used this strategy ‘almost always’. This strategy may help students to sound natural and to continue their conversation.

Speaking Strategy 7: If I do not hear a word or phrase clearly, I relate it to the part of the conversation that I understood.

At all three levels, the highest percentage of students' use of this strategy was found at the ‘quite frequently’ point of the scale. Fifty per cent of intermediate students reported use of this strategy when they failed to understand a word or phrase in English in exchanges. At lower rates, 40.3% of advanced students and 31% of beginner students also made use of this strategy. It seems that students are trying to maintain the conversational flow by not stopping it as soon as they face a comprehension problem.

Speaking Strategy 8: I use known words and phrases when I do not know how to say something.

The highest percentage of use was found at the ‘quite frequently’ point of the scale. A total of 48.5% of intermediate students stated using this strategy ‘quite frequently’, while 43.8% of advanced and 38.9% of beginner students also made use of the strategy ‘quite frequently’. Although this strategy is considered as a tool for not interrupting communication when interacting in English, it is not a resource used to its full potential by students at all three levels. Thus it is important to provide students with strategy training to enable them to compensate for unknown knowledge in order to keep their conversation going.

Speaking Strategy 9: I structure some ideas in my mind before speaking.

Students at all three levels make use of this strategy ‘quite frequently’. The highest percentage is among intermediate students, at 43.6%, while the lowest percentage of use is among beginner students, at 39.6, perhaps because beginners are in the process of acquiring vocabulary and structures. However, it is important to make students aware of the importance of giving some structure to their ideas from the beginner level.

Speaking Strategy 10: To gain time, I use fillers such as: and, well, etc.

A total of 46.5% of beginner students stated using this strategy ‘quite frequently’. Lower percentages at the same point of the scale were reported by intermediate students (43.6%) and advanced students (38.8%). It may be that students at intermediate and advanced levels have more resources to keep a conversation going so that they do not tend to use this strategy as frequently as beginner students. However, it is important to make students aware of the use of fillers in order to sound more natural. Students should also be introduced to a range of fillers in order not to limit their use to one or two.

Speaking Strategy 11: I repeat the last word or phrase I said to gain time.This strategy is not a prevalent one among students in the five universities, since most of them reported using it only ‘sometimes’ when speaking in English. The highest percentage of use was found at the ‘sometimes’ point of the scale by intermediate students (47.2%), followed by beginner students (45.5%) and advanced students (36.4%). Students should be trained to use this strategy as a tool to organise their ideas and gain time.

Speaking Strategy 12: I do not think too much before speaking so that ideas can flow in English.

This strategy seems not to be predominant among beginner (41.0%) and intermediate (36.3%) students, since they reported using it only ‘sometimes’ when interacting in English. In contrast, 37.5% of advanced students reported the use of this strategy ‘quite frequently’. Therefore it seems that beginner and intermediate students do not take time to prepare when speaking in English. Thus, it is necessary to train students from the lower levels to organise their ideas before actually speaking in class activities.

Speaking Strategy 13: I ask my speaking partner to repeat or explain with different words what I did not understand.

This strategy seems to be widely used by students at all three levels in the five public universities. The highest percentage of use is at the ‘almost always’ point of the scale among all three levels. A percentage of 42.6 of advanced students reported using this strategy ‘almost always’, followed by 42.4% of beginner students and 39% of intermediate students. Perhaps students use this strategy from the first levels of their language learning and it represents a useful tool, since they continue using it at higher levels.

Speaking Strategy 14: I tell my speaking partner when I do not understand something.

This strategy helps learners to keep the conversation going, but it is not widely used by students. The highest percentage of its use was found at the ‘quite frequently’ point of the scale among 34.2% of beginner students, followed by 32.7% of intermediate students. The highest percentage of use reported by advanced students was found at the ‘sometimes’ point of the scale, at 32.6%. Thus students at higher levels may not use this strategy frequently because they do not want to show their lack of proficiency in the language, or because they use other resources to aid comprehension.

Based upon the above analysis, the strategies most often used by students of the three levels of proficiency are the following:

Beginners

1. If I do not know how to say a word or phrase, I ask a classmate or my teacher (‘almost always’).

2. I use the dictionary to prepare a role play or communicative activity in class(‘almost always’).

3. To gain time, I use fillers such as: and, well, etc. (‘quite frequently’).

4. I do not think too much before speaking so that ideas can flow in English (‘sometimes’).

5. I tell my speaking partner when I do not understand something (‘quite frequently’).

The strategy used most by beginners is asking a classmate or a teacher for the unknown vocabulary or structure, which is understandable because these students are starting to build a vocabulary corpus and to manage certain basic structures. Thus it is advisable to train beginner students in other strategies so as to provide them with other tools when speaking in English.

Intermediate

1. If I do not hear a word or phrase clearly, I relate it to the part of the conversation that I understood (‘quite frequently’).

2. I use known words and phrases when I do not know how to say something (‘quite frequently’).

3. I ask my speaking partner to repeat a word or phrase if I do not hear it clearly (‘almost always’).

4. I structure some ideas in my mind before speaking (‘quite frequently’).

5. I repeat the last word or phrase I said to gain time (‘sometimes’).

Intermediate students seem to make more use of their previous knowledge when engaged in interactional exchanges in English. These students appear to be more confident of their language knowledge, thus making more use of what they already know rather than asking a teacher or classmate.

Advanced

1. If I do not know how to say a word, I use a synonym or describe what I want to say (‘almost always’).

2. If I do not know how to say a word in English, I say it in Spanish (‘sometimes’).

3. If I do not know how to say a word or phrase, I use gestures and my hands (‘quite frequently’).

4. I ask my speaking partner to repeat a word or phrase if I do not hear it clearly (‘almost always’).

5. I ask my speaking partner to repeat or explain with different words what I did not understand (‘almost always’).

Advanced students use more complex strategies, as shown above. It seems that these students feel more confident in their language knowledge and use more interactional strategies that are present in real-life oral exchanges.

The results of the second stage of the study reported similar results to those obtained in the first stage with the UQROO students. Beginner students use speaking strategies to compensate for their lack of knowledge; intermediate students tend to make more use of their previously acquired knowledge, resorting to language that they already know; and advanced students seem to use more strategies that allow them to continue the conversation without interrupting the flow. These students appear to be using different strategies in accordance with their language proficiency. This is in line with results found in other studies such as Vandergrift (2003) and Griffiths (2003).

Conclusions

The purpose of the study was to find out which speaking strategies students of these five public universities were using the most. It is important to note that although students from all five universities tend to use a range of strategies during their degree years, it seems that they tend to use different strategies at specific levels of language proficiency. This does not imply that students of different levels do not use other strategies. Participants at the three levels of proficiency identified using all the strategies reported by UQROO students in the preliminary study, but at different rates of frequency. The results that emerged from students’ questionnaires support the observations made in existing literature. For instance, Griffiths (2003) found that advanced students tend to use more sophisticated and interactive strategies than lower-level students. The same result was found in Vandergrift’s (2003) study, where more proficient learners employed metacognitive strategies more frequently than less proficient learners. Thus, it seems that levels of proficiency influence the type of strategy employed by learners.

Students in this study from the five public universities seem to use a wide range of speaking strategies in their language classes. Students at UNACH and UNACAR appear to use more speaking strategies than students at the other universities. This study focused on student’ use of the SLLQ; thus there is no information on whether the teachers at these two institutions (UNACH and UNACAR) encouraged or trained students explicitly on the use of speaking strategies. The purpose of this study was to explore which strategies the students of the five universities used the most in order to develop a framework of strategy training for future use at UQROO. The results are encouraging, and provide us with valuable data that will allow teachers in the different BAs in ELT to analyse which strategies to introduce at the different English levels in order to give students the tools to maintain a natural flow in their spoken English. The three strategies used the most by students from the five universities are: asking for repetition, the use of paraphrasing or a synonym for unknown words, and asking for clarification of a message. The results will allow researchers to propose which strategies will be of more benefit for students at different language levels.

It is important to emphasise that teachers should implement strategy training in language courses. My suggestion is to intersperse speaking strategies in communicative activities designed by teachers, with some time devoted to demonstrating and to explaining the rationale behind each strategy. Thus, strategies should be presented and demonstrated first, with teachers then allowing time for practice of the strategy. Once a strategy has been practised for some time, a new strategy should be introduced. Next, teachers should encourage the use of those strategies already introduced in class activities so that students use as many strategies as possible in their learning process. Providing strategy training for students will hopefully help them to take better advantage of their learning.

References

Canale, M. (1983). From communicative competence to communicative language pedagogy. In J. C. Richards & R. W. Schmidt (Eds.), Language and Communication (2-27). Harlow, UK: Longman.

Chamot, A. U. (2005). Language learning strategy instruction: Current issues and research. Annual Review of applied Linguistics, 25, 112-130.

Chen, Y. (2007). Learning to learn: The impact of strategy training. ELT Journal, 61(1), 20-29.

Cohen, A. (1998).Strategies in Learning and Using a Second Language. New York: Longman.

Dörnyei, Z. & Scott, M. L. (1995). Communication strategies: An empirical analysis with retrospection. In J.S. Turley & K. Lusby (Eds.), Selected Papers from the Proceedings of the 21st Annual Symposium of the Deseret Language and Linguistics Society (155-168). Provo, UT: Brigham Young University.

Ellis, G. & Sinclair, B. (1989). Learning to Learn English. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Gallagher-Brett, A. (2007). What do learners’ beliefs about speaking reveal about their awareness of learning strategies? Language Learning Journal 35(1), 37-49.

Griffiths, C. (2003). Patterns of language learning strategy use. System 31, 367-383.

Hedge, T. (2000). Teaching and Learning in the Language Classroom. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Issitt, S. (2008). Improving scores in the IELTS speaking test. ELT Journal 62(2), 131-138.

Kellerman, E. (1991). Compensatory strategies in second language research: A critique, a revision, and some (non-) implications for the classroom. In R. Phillipson, L. Selinker, M. Sharwood Smith and M. Swain (Eds.), Foreign/Second Language Pedagogy Research (142-161). Clevendon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Méndez, M. (2007). Developing speaking strategies. In M. Méndez and A. Marín (Eds.), Effects of Strategy Training on the Development of Language Skills (73-102). Estado de México: Pomares-UQROO.

Méndez, M. and Marín, A. (2007). Effects of Strategy Training on the Development of Language Skills. Estado de México: Pomares-UQROO.

Mugford, G. (2007). How rude! Teaching impoliteness in the second-language classroom. ELT Journal, 62(4), 374-384.

Naiman, N., Frohlich, M., Stern, H. and Todesco, A. (1978). The Good Language Learner. Toronto: Ontario Institute for Studies in Education.

Nakatani, Y. (2005). The effects of awareness-raising training on oral communication strategy use. Modern Language Journal, 89 (1), 76-91.

O’Malley, J. M. and Chamot, A. U. (1990). Learning Strategies in Second Language Acquisition. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Oxford, R. L. (1990). Language Learning Strategies: What Every Teacher Should Know. Rowley: Newbury House.

Rubin, J. (1975). What the “good language learner” can teach us. TESOL Quarterly, 9, 41-51.

Rubin, J. (1981). The study of cognitive processes in second language learning. Applied Linguistics, 2, 117-131.

Stern, H. H. (1975). What can we learn from the good language learner? Canadian Modern Language Review, 31, 304-318.

Tudor, I. (1996). Learner-Centeredness as Language Education. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Vandergrift, L. (2003) Orchestrating strategy use: Towards a model of the skilled L2 listener. Language Learning, 53, 461-494.