Introduction

Identity, which once was researched in neighboring disciplines, especially psychology, anthropology, and sociology, became an intriguing topic of research among applied linguistics researchers after Peirce (1995) conducted her pivotal research on five adult immigrant language learners in Canada. This research caused a shift in second language acquisition (SLA) from predominantly psycholinguistic approaches to second language (L2) learning to sociological and anthropological aspects of language learning (Douglas Fir Group, 2016; Norton, 2013a).

Norton's (1997; 2000; 2001; Peirce, 1995) research on identity in L2 learning led to the creation of some new concepts including language learner's imagined communities (ICs) and a learner's investment in language learning. The three closely interrelated ideas of identity, investment, and ICs can be helpful in addressing numerous questions to extend our understandings of language learners’ experiences (Norton, 2019).

ICs of practice are communities in which the imagination of individuals helps them feel they belong to communities which are not immediately reachable (Wenger, 2010). This is in agreement with the wider ‘social turn’ in SLA that questions the idea of L2 learning as an essentially psychological practice and sees learners as part of a social world (Tajeddin et al., 2021).

As Norton and Toohey (2011) stated, people have direct interaction with individuals of various communities; however, Wenger (1998) noted that this direct engagement with community practices and investment in real relationships is not the only way individuals feel they belong to a community and form identities since they also show affiliation with communities that develop beyond the learners’ immediate environments and social networks. Therefore engagement and participation in the activities of these communities exist in the learners’ imagination.

In the field of SLA, the relevance of the construct of ICs is that the learners do not only have interaction with their concrete learning contexts, but also imagine sites which provide learning opportunities as influential as and “no less real than the ones in which they have daily engagement” (Norton, 2013b, p.8). According to Norton (2001), there is a direct relationship between the students’ ICs and their participation in the practices of the class. Thus, if the learners feel that there is a marked difference between their projected identity in ICs and their perceived identity expectations determined by others, they will not participate in the practices of the classroom (Norton, 2000).

In Norton's view (Norton, 2000; 2001; 2016; 2019; Norton & Pavlenko, 2019), the learner's ICs/identities and hopes for the future can strongly influence their agency, motivation, investment in language and literacy practices used in a classroom, resistance to language learning, and consequent progress in language learning. Learners invest in activities which enable them to have access to their ICs and multiple identities (Tajeddin et al., 2021). Therefore, when a learning context does not let the learners belong to their ICs, they invest less in such a context and may engage in practices which are not advantageous to their language learning or act to make changes in their learning context (Trentman, 2013). However, if a learning context helps the language learners belong to their ICs, they have more investment in learning (Norton, 2001; Norton & McKinney, 2011).

Due to the significance of language learners' ICs in the process of language learning, researchers should pay much more attention to the topic of a present or future imagined self (Dawson, 2017). The necessity of doing research on this construct is also recommended due to today’s heightened mobility. English is associated with a global community (Ryan, 2006) and has provided unparalleled amounts of symbolic capital for many learners (Bourdieu, 1991). Furthermore, in the 21st century, learners are able to participate in limitless spaces for socialization and learning due to the availability of digital innovations, mobility, and superdiversity (Darvin & Norton, 2015). These factors are influential in the range of ICs and what language learners can possibly imagine (Kanno & Norton, 2003). Hence, SLA researchers should explore the relationship between language learning, imagination, and identity more deeply to reveal the impacts of the learners' ICs on their identity construction and participation in learning (Dawson, 2017).

Literature Review

Imagined communities and language learning

The present study draws on the concept of ‘imagination’ to better understand the way English as a Foreign Language (EFL) learners approach learning English. Imagination can affect individuals' present (anticipatory) and future (anticipated) emotions. In fact, its significance lies in the emotions that are activated by imagining future states (MacIntyre & Gregersen, 2012). It provides hope for a better future and is a force for action (Appadurai, 1996). The focus on the future reflects considerable attention to the importance of imagination in learning and teaching (Norton & Kamal, 2003). Imagination should not be considered the same as fantasy. As Simon (1992) notes, there is a marked difference between “wishes,” in which no possibility exists for action, and “hopeful imagination,” in which action is essential in the fulfillment of hopes and desires and, subsequently, produces attempt for the desired future.

The construct of ICs was originally coined by Anderson (1991) and was used to represent the construction of a nation state. Anderson described nations as ICs because, ‘‘the members of even the smallest nation will never know most of their fellow-members, meet them, or even hear of them, yet in the minds of each lives the image of their communion’’ (p. 6).

Wenger's (1998) perspective of imagination as a way of involvement in communities of practice, or situated learning theory, extends Anderson’s framework of ICs to any community of practice a person desires to enter. Wenger argues that imagination is a unique mode of belonging to a specific community of practice via which people place themselves and other individuals in the world and bring to their identities “other meanings, other possibilities, other perspectives” (Wenger, 1998, p. 178).

Anderson's (1991) concept of imagined community was applied and connected to SLA by Norton (2000, 2001). In her research, Norton (2001) found that the desired community of two adult immigrant language learners was something more than the book and four walls of the classroom, not only spatially but also temporally. For these two learners, the classroom experiences did not improve their capability to belong to their ICs. The mismatch between their imaginations and reality caused these learners to give less effort in the class as a language learning experience and eventually withdraw from participation. This finding indicates that although the learners participate in a similar learning context, they may imagine multiple coexisting ICs which shape their attempts and engagement to learn another language (Teng & Bui, 2018).

According to Norton (2016), learners sitting in a classroom can envisage the world different from the existing realities and their identities are formed both by their real experiences and their investment in the tangible world and in the imaginable worlds. Muir et al. (2021) also maintained that "even when students do not or are not able to travel, teaching materials and other resources can help learners develop imagined transnational networks and identities, through imagining themselves engaging in communication with communities worldwide" (p. 5).

Learners' investment in particular ICs can be a remarkable force affecting the learners’ identity construction and driving language learning since the sense of being a member in an imagined global community of English users induces most language learners to show significant efforts into language learning (Norton, 2001; Ryan, 2006). It is assumed that having a vision of their ideal self as a foreign language speaker can be an influential force motivating learners to learn the language (Murray, 2013).

The participation of learners in their ICs reflects their agency (Dawson, 2017; Przymus, 2016; Sung, 2019). This happens since in ICs learners are enabled to keep a level of control and have the potential to reconstruct their identities and claim more powerful positions (Norton, 2020). Through their membership in these ICs, the learners can heighten their current and future aspirations and decisions and create a revelatory and evaluative context for such decisions, expectations, and their consequences (i.e., identity reconstruction) (Tajeddin et al., 2021). Since in ICs, the learners’ needs, desires, expectations, hopes for the future, and imagined identities are negotiated (Norton, 2020; Przymus, 2016; Sung, 2019), the learners can negotiate new investments and identities (Tajeddin et al., 2021).

One significant point about ICs is that their effects on the learners’ current identities, concomitant actions (and identity co-construction), and investment may be as strong as the communities in which they have regular involvement and even have a stronger effect on the learners’ investment (Kanno & Norton, 2003). Moreover, these desired communities can offer learners certain imagined identity options (Norton & McKinney, 2011) and expand L2 learners’ range of possible selves (Wenger, 1998). When students learn a language and imagine who they and their communities may be, in fact, they are focusing on the future (Norton & Toohey, 2011). This emphasis is a motivating source for their present activities (Kanno & Norton, 2003).

According to Kharchenko (2014), the learners' participation in some ICs can make the power available to alter existing real communities of participation or to replace a future imagined community instead of a real one. The important point is that a newly imagined community may not always be the best one. However, the argument is that the learners' non-participation in certain language practices can be determined through their investment in special ICs (Norton, 2000, 2001). As Song (2018) argues, the nonparticipation of language learners seems to reflect a kind of resistance to their marginalization in the contexts of learning which are not similar to their ICs.

Various studies (e.g., Dawson 2017; Norton, 2019, 2020; Przymus 2016; Sung, 2019) have demonstrated that it is necessary for teachers and teacher trainers to be cognizant of the learners’ access to ICs; otherwise, learners’ non-participation in language classrooms might increase. Although Norton (2001) states that teachers may worsen the learners' non-participation if they do not acknowledge the language learners' ICs in the language classrooms, she also notes that it may be very challenging for the teacher to acknowledge this community unconditionally. She proposes that the learners' desires, images, and memories should be the basis for radical renewal, and that language learners must be stimulated to say why they wish for what they want, and if these desires are in harmony with a vision of future possibility. They should also be asked to what extent such investments can be productive for their engagement in the broader target language community.

Przymus et al. (2020) proposed ways in which teachers may be enabled to facilitate learners’ engagement in ICs. First, they should try to know the learners and gain information about their interests. Then, they should make a connection among learners with similar interests. Next, they should establish physical and ideological third spaces (blended affinity spaces) for the learners to interact and meet (in person or online). Finally, they can contact the group and discuss the resources required and conduct action research regarding the learners’ perspectives on the effectiveness of blended affinity spaces.

Previous research on imagined communities

Imagined communities was the topic of the special issue of the Journal of Language, Identity, and Education in 2003 and the Journal of Language, Discourse, and Society in 2017. In these two issues, numerous researchers investigated the significance of the construct of ICs in language learning. For example, Blackledge (2003), who used the concept of ICs in examining racial discourses available in educational documents in the UK, criticized how Asian minorities were racialized in British schools. He employed critical discourse analysis to examine how school minorities were not permitted to have access to their heritage community. He found that the cultural practices of Asian minorities who visited their heritage countries regularly were marginalized due to the authorities’ imagination of a monocultural and monolingual community. Minority children were kept away from their home heritage culture because the British educational system believed access to the heritage culture could harm the imagined community that a language learner should develop to be successful.

Fourteen years later Dawson (2017) investigated the relationship between identities and ICs for two adult English language learners in a New Zealand university. Through naturally-occurring conversational data and a discourse analytic approach, Dawson explored how the two learners sought to construct the identities they individually considered as valuable in their particular ICs. The findings indicated that similarly-labeled ICs may give rise to dissimilar instances of language learners' identities and investments. Dawson found that the two learners’ individual imaginations of the specific identities necessary to attain membership in community were different, and this difference was considerably influential in their investments.

The concept of ICs has also been productive in other research sites. For instance, Kendrick and Jones (2008) did their research in Uganda and aimed to examine photographs and drawings provided by primary and secondary girls. They employed multimodal methods to examine the girls’ insights about their participation in local literacy practices. The girls’ visual images represented their ICs. In these communities, mastery of English and access to education was obtainable. Providing chances for these girls to reflect their worlds via alternatives ways of communication served as a pedagogical approach with substantial potential; it prepared the ground for having dialogue about gender inequities and representing ICs where those inequities were not available.

Trentman's (2013) study examined the imagined community of study abroad in the Middle East to which American students studying in Egypt wished to belong and compared it to the reality of the communities of practice (Lave & Wenger, 1991; Wenger, 1998) with which they engaged while abroad. In the Middle East, the students envisaged belonging to an imagined community of study abroad. As members of that imagined community, they could connect others dedicated to enhancing mutual understanding between East and West. To belong to this community, it was necessary for them to reveal the identities of a dedicated language learner and cross-cultural mediator. Being a member in this imagined community was essential for the students to reach their goals using the Arabic language. It was demonstrated that the degree of alignments and misalignments between their imagination and the realities they encountered impacted how much the students invested in their study abroad as a language learning experience.

Sung (2019) investigated a Hong Kong undergraduate student’s experiences in various situations, in and outside the classroom on a university campus and in their workplace while studying abroad. The results showed the close connection of the learner's differential L2 investments across various contexts and their different identities constructed in particular situations. What formed the learner’s strategic L2 investments was the strong desire to be in an imagined global community and have an imagined identity connected to a cosmopolitan way of life in the projected future.

Tajeddin et al. (2021) examined ICs of practice in the context of English as an International Language (EIL). These researchers used a mixed-methods design to investigate English language learners’ outlook on their imagined community of practice for employing English in the context of EIL. e A questionnaire about imagined communities of practice was completed by 592 respondents and 64 participants were interviewed. The findings from the questionnaire and interview data indicated that the participants found ICs of practice could create opportunities for English language users to (a) mould their language learning identity, (b) communicate globally, (c) preserve values connecting English language users, (d) gain learner agency, and (e) practice synergy and coordination in their ICs.

Language learning and teaching are typically considered to take place in face-to-face communities of practice. Hence, the connection between learning and the learner’s participation in a wider imagined world has not been explored as it deserves (Block, 2007). In contrast to communities of practice, previous research on ICs of practice is limited yet illuminating (Tajeddin et al., 2021). Taken together, these studies indicate that ICs play a key role in the language learners’ engagement in learning (Norton, 2019; Przymus, 2016; Tajeddin et al., 2021).The study of language learners' ICs is a growing field. Although the literature is rich in the effect of ICs in English as a second language (ESL) and EFL contexts, to date, there are insufficient published accounts on this construct in the Iranian EFL context. In addition, the previous research on ICs has mainly considered the issue in question from a qualitative standpoint (Tajeddin et al., 2021). Sociolinguistic researchers generally prefer to utilize qualitative approaches in their studies since through these approaches it is possible to provide detailed accounts of individuals (Gao et al., 2015). However, the major criticisms leveled against them are that they are time-consuming, costly for administration and scoring (Khatib & Rezaei, 2013a), and less generalizable due to the existence of usually less than ten participants in studies using qualitative approaches (Rezaei, 2017). These potential problems of qualitative approaches justify the use of quantitative approaches since they can help researchers tackle the problems inherent in qualitative approaches and provide the ground for ongoing research and reaching more generalizability (Khatib & Rezaei, 2013a).

A quick review of the literature indicates that many researchers have ignored quantitative research methods in their studies on ICs. The present study aims to explore the EFL learners' investment in their ICs to fill this void in the literature through the use of a validated questionnaire in the Iranian context, where the number of EFL learners is on the increase and the growing preoccupation with foreign language competence is constantly noticeable.

Purpose of the Study

The present study aimed to survey English language learners’ ICs in the Iranian context. Its distinctive feature was that it sought to overcome the common researchers' extreme attention to essentially qualitative approaches in research on language learners' ICs by employing a valid questionnaire to obtain a more tangible and generalizable image of this construct.

ICs in this study is primarily known as the learner's imaginations and thoughts in the process of language learning in the classroom or outside and consists of eight components of "imagination and the learners' desires for belonging and recognition, expanding one's range of possible selves by ICs, marginalization, non-participation, and resistance in language classroom or outside, trying to attain a legitimate membership (moving from peripherality to legitimacy), gender, power, and material inequalities, access to different capitals (economic, cultural, social, and symbolic), identity construction and promotion, and finally language learner's agency" ( Soltanian et al., 2020, p. 167). What constitutes language learner's ICs in this study is operationalized via a model and actualized in a questionnaire developed and validated by authors and colleagues.

One concern which stimulated the present research was the approach employed by researchers in their studies on language learner's ICs. They most commonly were conducted via qualitative approaches˗ particularly interviews˗ and as a result, quantitative and mixed-methods approaches have not been widely used by the researchers. Since identity research was initially done by researchers in the neighboring fields of psychology, anthropology, and sociology, a review of research in these disciplines shows that these researchers have generally employed quantitative approaches or mixed-methods measures for exploring identity issues (Khatib & Rezaei, 2013a). Moreover, considering many complex constructs in applied linguistics, e.g., language motivation, language competence, language anxiety, language identity, and recently, investment in language learning, have been researched with quantitative measures, research on ICs can similarly be done with quantitative or mixed-methods research tools.

Since the role of the learners' demographic characteristics has not been considered in their ICs, the present research also included the impact of the learners' gender, age, and language proficiency on ICs. Considering the foregoing, the following research questions were addressed in this study:

1. To what extent do Iranian EFL learners invest in their ICs/identities?

2. Are there any significant differences between Iranian EFL learners’ extent of investment in ICs/identities and the demographic features including gender, age, and English language proficiency level?

Materials and Methods

Participants

This study used stratified random sampling together with cluster sampling. Eight provinces were included as the strata and the institutes and universities were chosen as the clusters. A total of 945 Iranian EFL learners filled out the questionnaire. These participants were male and female with different academic degrees and belonged to different age groups and language proficiency levels. Their lengths of language learning experience differed (ranging from 3 to 144 months with a mean of 39 months). They were mostly enrolled in 90-mintute non-compulsory English classes in the language colleges at the universities or the private language institutes. Their courses varied from A1 to C2 based on the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR). The reason for this diverse selection of the participants was to get better generalizability of findings.

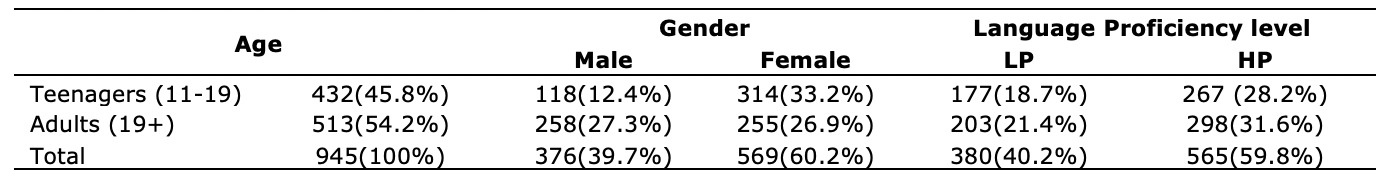

The descriptive statistics for the participants’ age, gender, and language proficiency level are displayed in Table 1 below. In this study, the participants self-reported their language proficiency level based on the textbooks they studied at their colleges or institutes. To facilitate data analyses and reports, the participants were divided into two groups in terms of age and language proficiency. Regarding language proficiency, two different classifications were considered: low proficiency (LP) (which included basic, elementary, and pre-intermediate levels) and high proficiency (HP) (which included intermediate, high intermediate, and advanced levels). The authors also classified the participants’ age into two categories: teenagers (11-19 years old) and adults (+19 years old).

Table 1: Participants' age, gender, and language proficiency level

According to the results shown in Table 1, the number of teenagers (45.8%) was less than that of the adults (54.2%). The Table also shows that females make up the greatest number of participants (60.2%) followed by males with 39.7%. Moreover, Table 1 shows that 40.2% of the participants belonged to the LP group and 59.8% were in the HP group.

Instrument

The instrument employed in the present study was a survey questionnaire of language learner's ICs developed and validated by Soltanian et al. (2020). Generally, the reason for using questionnaires is that they can tap into the learners’ views, preferences for specific practices, and values (i.e., preferences for ‘life goals’ and ‘ways of life’) and can be employed to describe the usefulness and importance of particular activities (Dörnyei & Taguchi, 2010).

The questionnaire used in this study explored the respondents’ imaginations and ICs while learning English language. It was developed based on a hypothesized model of a language learner's ICs with eight components (mentioned previously in the Purpose of the Study) and validated through confirmatory factor analysis. Its reliability index was 0.95 which is a high index of Cronbach alpha. The questionnaire contained 57 items including all the eight components of language learner's ICs. Each item in the questionnaire was based on a six-point Likert-type scale including strongly agree, agree, slightly agree, slightly disagree, disagree, and strongly disagree. It contained a demographic section inquiring about the participants’ gender, age, English language proficiency level, English accent preferred, educational background, place of residence, and length of language learning experience.

Data collection procedure

To collect data, the questionnaire was administered to 1357 English language learners across Iran, however, only 1103 learners returned it. They filled it out either online through Telegram, WhatsApp, or email (84%) or by hand (16%) in their classrooms at institutes or universities. In order to increase the return rate, the researchers had also translated the items into Persian language so that the participants who belonged to lower language proficiency levels could complete the questionnaire easily. All the participants were free to participate. While administering the questionnaire, they were informed that their participation was voluntary and that they could withdraw at any time they liked.

Data analysis

After data collection, descriptive statistics and t-tests were run using SPSS as the main statistical methods. The questionnaire data were examined for missing data, and of the 1103 questionnaires collected, 158 ones did not provide sufficient data and were deleted from the final data analysis. Eventually, the questionnaires returned by 945 respondents were considered in this study.

Results

The first research question: EFL learners’ investment in their ICs/identities

To determine the students’ investments in their IC identities, the authors calculated the scores from the questionnaire. The scales were arranged from 1 to 6 with strongly disagree at one end of the scale with 1 point and strongly agree at the other end with 6 points. Consequently, the minimum score possible was 57 and the maximum was 342. Before running the SPSS, some items were reverse-coded since they were negatively keyed.

The mean and standard deviation of the whole questionnaire were calculated to classify the scores statistically. The scores which fell one standard deviation below and above the mean were taken as low and high scores, respectively, and the scores falling between these two were considered to belong to the moderate zone. The scores were interpreted in this way: the higher the scores were, the more the participants showed investment in their ICs/identities.

The findings showed that the mean score and the standard deviation gained from the questionnaire were 280.42 and 54.22, respectively. Consequently, the scores between 226.20 and 334.64 were taken as moderate and those below 226.20 and above 334.64 belonged to the participants who showed low and high extents of investment in ICs/identities, respectively. The findings indicated that the majority of the respondents demonstrated a moderate level of investment in ICs/identities. More specifically, 60.3 % belonged to those who moderately invested in their ICs/identities and 14.8% and 24.9% were those who showed low and high extents of investment in their ICs/identities, respectively.

The second research question: Iranian EFL learners’ extent of investment in ICs/identities and their demographic features

The second research question of the study had three sub-questions, It was broken down into three distinct null hypotheses to facilitate data analyses and make results easier to understand.

H01: There is no statistically significant difference between male and female participants and the extent of their investment in ICs/identities.

H02: There is no statistically significant difference between teenagers and adults and the extent of their investment in ICs/identities.

H03: There is no statistically significant difference between the low- and high-proficiency learners and the extent of their investment in ICs/identities.

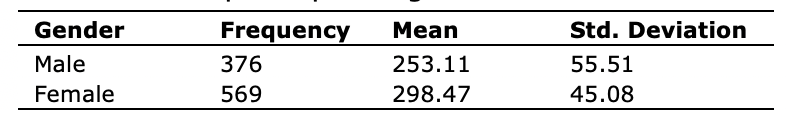

To test the first null hypothesis, a t-test was run to compare the scores of the male and female participants and conclude which group enjoyed a higher level of investment in ICs/identities. Table 2 presents the descriptive statistics for the participants' gender.

Table 2: Descriptive statistics for male and female participants

The results in Table 2 show that the mean for the female participants was greater than the mean of the male (male= 253.11, and female= 298.47). However, an independent samples t-test was run to ensure the difference was significant. The results of this comparison are shown in Table 3.

Table 3: Independent samples T-test for gender

As the results in Table 3 show, t(945) =-13.789, p=0.00. This finding indicates that there was a significant difference between the extent of investment in ICs/identities in male and female groups. Therefore, the first null hypothesis is rejected and it is concluded that Iranian male and female EFL learners show different levels of investment in ICs/identities in this study.

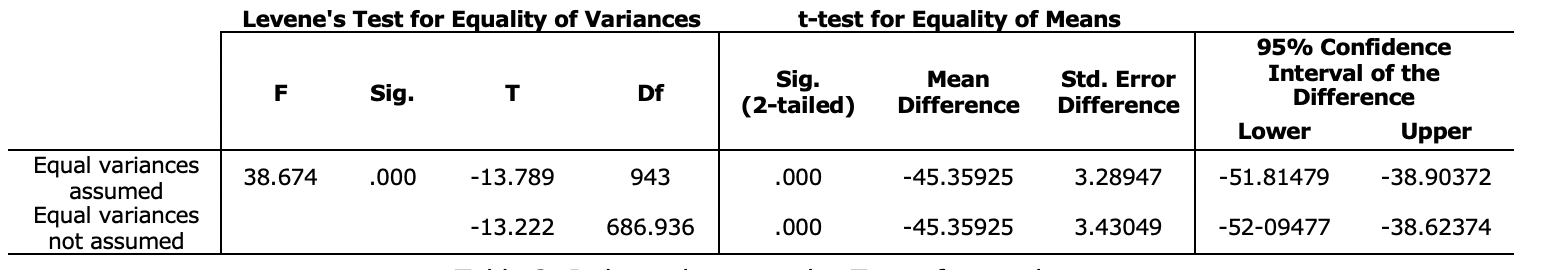

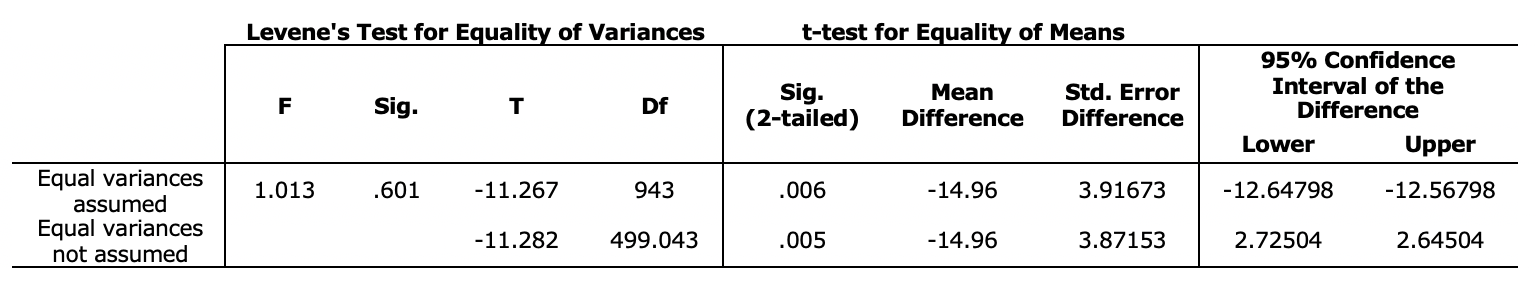

To test the second null hypothesis, another independent t-test was run to compare the extent of investment in ICs/identities in the teenagers with that of the adults. Table 4 presents the results of the descriptive statistics for the participants’ age.

Table 4: Descriptive statistics for different age groups

As Table 4 shows, the mean of the teenage group was higher than the mean of the adult group (teenagers= 286.51, and adults= 275.30). An independent t-test was again run to make sure this difference was significant. Table 5 reports the results of t-test for age.

Table 5: Independent samples T-test for age

Table 5 shows that t(945) = 3.180, p<.05. This finding indicates that the null hypothesis is rejected. It was concluded that there was a significant difference in the extent of investment in ICs/identities between the participants of these two age groups.

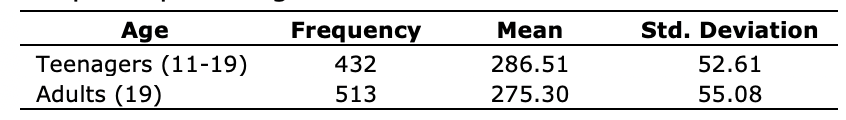

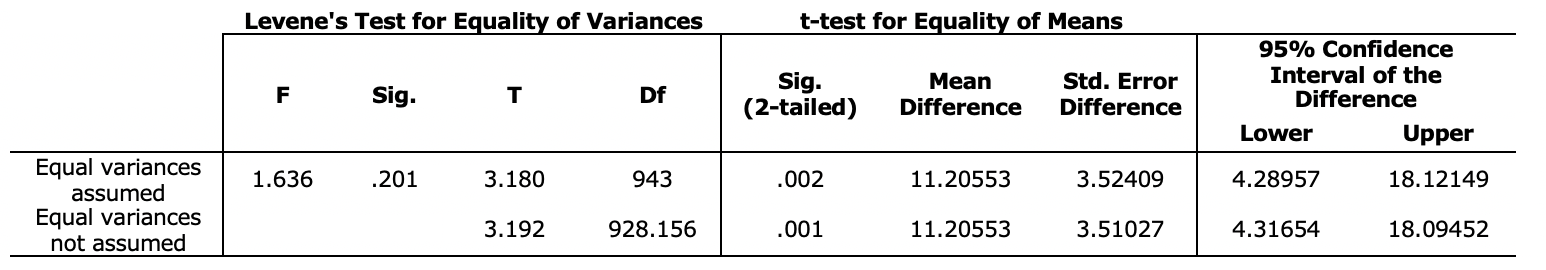

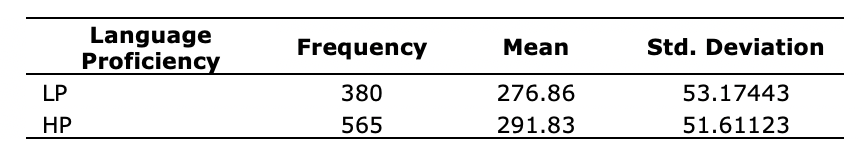

To test the third null hypothesis, the extent of investment in ICs/identities between the participants in the HP group and those in the LP group was compared. In Table 6, the descriptive statistics for this section can be seen.

Table 6: Descriptive statistics of the participants from different language proficiency levels

Table 6 indicates that the means for the LP and HP groups were 276.86 and 291.83, respectively. The latter group showed a higher mean; however, an independent t-test was run to make sure the difference was significant. Table 7 illustrates the results of t-test for language proficiency.

Table 7: Independent samples T-test for language proficiency

Based on Table 7, t(945) =-11.267, p<0.05. This result demonstrates that the third null hypothesis is rejected since there was a significant difference between the extent of investment in ICs/identities in the learners belonging to the LP and HP groups in this study.

Discussion

This quantitative study investigated Iranian English language learners' investment in their ICs/identities since little research on these communities had been conducted previously. The findings indicated that the majority of Iranian EFL learners possessed a moderate level of investment in their ICs/identities. Moreover, there was a significant difference between male and female participants in the extent of investment in their ICs/identities, females showing more investment in this regard. This significant difference was also true between the teenagers and adults since teenagers were more invested in their ICs/identities. The results also indicated that there was a significant difference between the LP and HP groups concerning their extent of investment in ICs/identities, with the second group being more invested in their ICs/identities.

A possisble reason why Iranian EFL learners showed a moderate level of investment in their ICs/identities could be the close dependence of identity, investment, and ICs among language learners (Kanno & Norton, 2003; Mohammadian Haghighi & Norton, 2017; Norton, 2000, 2001, 2015, 2016; Norton & Pavlenko, 2019). .These EFL learners possessed a moderate level of language identity (Rezaei et al., 2014) and investment in language learning (Soltanian et al., 2018). Hence, it is not surprising to see that these learners moderately invested in their ICs/identities. On the other hand, there can be various reasons why these learners demonstrated a moderate level of investment in their ICs and more in-depth research is needed to focus on an explanation of this issue. A more in depth study based on an ethnographic approach with a small group of language learners may be useful.

The male and female learners in this study were statistically different in the extent of investment in their ICs, perhaps explained by the idea that learning English may lead to different outcomes and provide diverse opportunities for individuals of different genders. In numerous situations, English may provide learners with the chance of imagining diverse gendered identity options (Norton & Pavlenko, 2019). Many women across the world consider learning English as a way to liberate themselves from the restrictions of a gender-based patriarchy (Kobayashi, 2002; Mohammadian Haghighi & Norton, 2017). Women in Iran could be experiencing a different context in English language classrooms (Mohammadian Haghighi & Norton, 2017), because compared to males, many young women in Iran have less mobility since they are marginalized from mainstream Iranian society, and English classes are considered as a particularly ideal type of recreation for them. Such classes, in comparison to classrooms for other subjects, may provide Iranian EFL learners in general and females, in particular, with a broader range of ICs/identities. By attending language classes, Iranian women could improve their knowledge of numerous cultures, socialize with their peers, and develop the range of imagined identities which could exist for them (Kanno & Norton, 2003; Norton, 2013b). Hence, learning English could provide Iranian women with opportunities to broaden their horizons and expand the range of opportunities available to them (Mohammadian Haghighi & Norton, 2017). English also could represent the opportunity to provide gender equity for them (Norton & Pavlenko, 2019).

The findings of this part of the study agree with those of Mohammadian Haghighi and Norton (2017). These researchers concluded that female learners showed more investment in language learning and their higher level of investment was effective in their imagined identities. The learners’ imagined identities were principally salient to their investment in the activities used in English classes. Iranian females, in general, may also have more investment in language learning (Soltanian et al., 2018). This higher level of investment may be influential in the females’ higher investment in ICs as indicated in this study.

The findings of the study suggested that although the number of teenagers was fewer than that of the adults, the first group possessed more investment in their ICs than the latter one. The reason may be because in comparison to teenage learners, adult learners have shaped their identity and it is not so easy for them to create imagined identities for themselves. Although they may have ICs for themselves, they are not as strong as the ones developed by the teenagers. Adolescence is considered as an important phase of human development which is closely connected with identity issues (Harklau & Moreno, 2019). Moreover, teenage English learners are developing and leaning English at a time when some societal changes such as transnationalism, globalization, and the rapidly developing digital age have led to a significantly different social and virtual environment (Harklau & Moreno, 2019). Being at the “forefront of globalization” (Fuligni & Tsai, 2015, p. 413), and crossing the broadest scopes of social contexts in the process of identity development and formation, adolescents are assumed to be different from children and adults (Yoon et al., 2017).

In this study, the EFL learners in the HP group were more invested in their ICs. This may be due to the perception that knowing English can affect their identities in noninteractive ways and that the language the individuals acquire determines the way they construct their vision of the world. Learning English allows learners to distance themselves from their own culture or singular cultural perspective (Kim, 2003). Seemingly, learners with a high level of language proficiency are more aware of other paradigms and do not limit themselves to their own native language's worldviews, so they can experience more complex imagined identities. In fact, a more reflective and critical attitude toward an individual's own culture accompanies knowledge of English (Kim, 2003). Another simple reason for demonstration of more investment in ICs on the part of the HP group may be the larger number of participants in the HP group in comparison to the LP group. Of course, this can be considered as one limitation in the present study and further studies are required with equal number of participants in each language proficiency group to see if this finding is confirmed.

The results obtained in this section are partly in line with those of Kim's (2003) study. Although Kim did not directly refer to ICs/identity in her research and used words such as transcending cultural boundaries and accessing other worldviews through proficiency in English language, the findings of her study can be compared with this part of the study. Both studies showed that higher proficiency in English can be effective in broadening minds and becoming aware of other possibilities in the future. This finding can also be compared with those of Khatib and Rezaei (2013b). In their study, they concluded that the learners in higher levels of proficiency show more enthusiasm about English language and culture and that their higher investment and construction of ICs can contribute to better development of L2. It can be argued that the sense of belonging to certain groups can be effective for language learners since through this feeling they attempt to approximate themselves to the L2 norms (Khatib & Rezaei, 2013b).

Conclusion

This study aimed to address the researchers’ excessive focus on qualitative approaches in research on language learners' ICs. To this end, the authors employed a valid questionnaire measuring the extent to which Iranian EFL learners were invested in their ICs. The current study, which has provided a general image of some Iranian EFL learners’ investment in their ICs/identities, can inform teachers about the nuances of language learners. It focuses on the improvement of teaching practices by altering fixed views about language learners because they have their own interpretation of themselves and the practices in which they are engaged. For example, in Iran the learners have many reasons for going to English classrooms and they do the language activities with goals in mind. Some language learners do classroom activities and limit limit themselves to the classroom context, while others imagine contexts outside the classroom where they might use that task. The future projections of the second group of language learners lets them fly out of the four walls of the classroom and envision the future applications of the activities.

Considering the significant point that students invest in practices that provide the opportunity to gain access to their ICs/identities (Darvin & Norton, 2019), teachers should know about their students' social status, language and cultural background, commitment to learn another language, and their imaginations while language learning and value their aspirations, needs, and desires concerning their use of a foreign language. Hence, they should design activities through which the diversity of learners is appreciated and the numerous histories, identities, and imaginations that they have in the class are confirmed (Darvin & Norton, 2018). Through instruments such as interviews, surveys, classroom observation, and journal entries, teachers can identify the types of ICs their learners would desire to be connected to and the imagined identities they attempt to reconstruct (Tajeddin et al., 2021).

The present study suffers from some shortcomings. The most important of which is the data collection instrument. Questionnaires have many advantages for conducting research, for example they are appropriate instruments for ongoing research and large-scale surveys in a short time, meeting generalizability in results, being scored objectively, providing rich data, and making it possible to extrapolate data simply. However, in conducting research studies it is often better to combine quantitative approaches with qualitative ones to collect a more complete source of data (Rezaei, 2017).

Future research on ICs can explore how paying attention to language learners' ICs/identities within the class impact their investment in language learning and offer them chances for the future. Examining the effects of other variables, such as place of residence, economic status, and ethnicity on ICs is something which also requires further investigation. In addition, the participants in this study were learning English in private language institutes or language colleges. Other research studies can investigate learners’ ICs in state schools or universities. Another issue for future research is taking the contextual nature of constructs such as ICs into consideration, so future researchers could investigate this construct in other EFL contexts.

Finally, it is restated that in EFL classes, teachers should be aware of the learners’ ICs and discuss them in the class (Tajeddin et al., 2021) because undervaluing of these communities on the part of the teachers may serve as a roadblock to attaining required continuity for the language learners’ learning and the feeling of belonging to particular communities (Przymus et al., 2020). Hence, the teacher should seek to recognize what investments the learners may have in the classroom, what their imagined identities are, and how the teacher can assist them in navigating their experiences in the most enriching and satisfying ways possible (Soltanian & Ghapanchi, 2021).

References

Anderson, B. R. O. A. (1991). Imagined communities: Reflections on the origin and spread of nationalism. Verso.

Appadurai, A. (1996). Modernity at large: Cultural dimensions of globalization. University of Minnesota Press.

Blackledge, A. (2003). Imagining a monocultural community: Racialization of cultural practice in educational discourse. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 2(4), 331-347. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327701JLIE0204_7

Block, D. (2007). Second language identities. Continuum.

Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Harvard University Press.

Darvin, R., & Norton, B. (2015). Identity and a model of investment in applied linguistics. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 35, 36-56. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190514000191

Darvin, R., & Norton, B. (2018). Identity, investment, and TESOL. In J. I. Liontas & M. DelliCarpini (Eds.), The TESOL encyclopedia of English language teaching. Wiley.

Darvin, R., & Norton, B. (2019). Collaborative writing, academic socialization, and the negotiation of identity: Authors, mentors, and gatekeepers. In P. Habibie & K. Hyland (Eds.), Novice writers and scholarly publication: Authors, mentors, gatekeepers (pp. 177-194). Palgrave Macmillan.

Dawson, S. (2017). An investigation into the identity/imagined community relationship: A case study of two language learners in New Zealand. Language, Discourse & Society, 5(1), 15-33.

Dörnyei, Z., & Taguchi, T. (2010). Questionnaires in second language research: Construction, administration, and processing(2nd ed.). Rutledge.

Douglas Fir Group. (2016). A transdisciplinary framework for SLA in a multilingual world. The Modern Language Journal, 100(51), 19-47. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12301

Fuligni, A.J., & Tsai, K.M. (2015). Developmental flexibility in an age of globalization: Autonomy and identity development among immigrant adolescents. Annual Review of Psychology, 66(1), 411-431. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-010814-015111

Gao, Y., Jia, Z., & Zhou, Y. (2015). EFL learning and identity development: A longitudinal study in 5 universities in China. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 14(3), 137-158. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2015.1041338

Harklau, L. & Moreno, R. (2019). The adolescent English language learner: Identities lost and found. In X. Gao (Ed.), Second handbook of English language teaching (pp. 601-620). Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

Kanno, Y., & Norton, B. (2003). Imagined communities and educational possibilities: An introduction. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 2(4), 241-49. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327701JLIE0204_1

Kendrick, M. & Jones, S. (2008). Girls’ visual representations of literacy in a rural Ugandan community. Canadian Journal of Education, 31(2), 371-404. https://journals.sfu.ca/cje/index.php/cje-rce/article/view/3007/2295

Kharchenko, N. (2014). Imagined communities and teaching English as a second language. Journal of Foreign Languages, Cultures, and Civilizations, 2(1), 21-39. http://jflcc.com/journals/jflcc/Vol_2_No_1_June_2014/2.pdf

Khatib, M., & Rezaei, S. (2013a). A model and questionnaire of language identity in Iran: A structural equation modeling approach. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 34(7), 690-708. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2013.796958

Khatib, M., & Rezaei, S. (2013b). The portrait of an Iranian as an English language learner: A case of identity reconstruction.International Journal of Research Studies in Language Learning, 2(3), 81-93. https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrsll.2012.176

Kim, L. S. (2003). Multiple identities in a multicultural world: A Malaysian perspective. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 2(3), 137-158. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327701JLIE0203_1

Kobayashi, Y. (2002). The role of gender in foreign language learning attitudes: Japanese female students’ attitudes toward English learning. Gender and Education, 14(2), 181-197. https://doi.org/10.1080/09540250220133021

Lave, J., & Wenger, E. (1991). Situated learning: Legitimate peripheral participation. Cambridge University Press.

MacIntyre, P., & Gregersen, T. (2012). Emotions that facilitate language learning: The positive-broadening power of the imagination. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 2(2), 193-213. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2012.2.2.4

Mohammadian Haghighi, F., & Norton, B. (2017). The role of English language institutes in Iran. TESOL Quarterly, 51(2), 428–438. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.338

Muir, C., Dörnyei, Z., & Adolphs, S. (2021). Role models in language learning: Results of a large-scale international survey.Applied Linguistics, 42(1), 1–23. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/amz056

Murray, G. (2013). Pedagogy of the possible: Imagination, autonomy, and space. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 3(3), 377-396. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2013.3.3.4

Norton, B. (1997). Language, identity, and the ownership of English. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 409- 429. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587831

Norton, B. (2000). Identity and language learning: Gender, ethnicity, and educational change. Pearson Education.

Norton, B. (2001). Non-participation, imagined communities, and the language classroom. In M. Breen (Ed.), Learner contributions to language learning: New directions in research (pp. 159-171). Pearson Education.

Norton, B. (2013a). Identity, literacy, and English language teaching. Iranian Journal of Language Teaching Research (IJLTR), 1(2), 85-98. https://ijltr.urmia.ac.ir/article_20443_7f04a7f219957f676cb246b0b0ceaa66.pdf

Norton, B. (2013b). Identity and language learning: Extending the conversation (2nd ed.). Multilingual Matters.

Norton, B. (2015). Identity, investment, and faces of English internationally. Chinese Journal of Applied Linguistics, 38(4), 375-391. https://doi.org/10.1515/cjal-2015-0025

Norton, B. (2016). Identity and language learning: Back to the future. TESOL Quarterly, 50(2), 475-479. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.293

Norton, B. (2019). Identity and language learning: A 2019 retrospective account. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 75(4), 299-307. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.2019-0287

Norton, B. (2020). Identity and second language acquisition. In C. A. Chapelle (Ed.), The concise encyclopedia of applied linguistics (pp. 561–570). Wiley.

Norton, B., & Kamal, F. (2003). The imagined communities of English language learners in a Pakistani school. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 2(4), 301-317. https://doi.org/10.1207/S15327701JLIE0204_5

Norton, B., & McKinney, C. (2011). An identity approach to second language acquisition. In D. Atkinson (Ed.), Alternative approaches to second language acquisition (pp. 73-94). Routledge.

Norton, B. & Pavlenko, A. (2019). Imagined communities, identity, and English language learning in a multilingual world. In X. Gao (Ed.), Second handbook of English language teaching (pp. 703-718). Springer Nature Switzerland AG.

Norton, B., & Toohey, K. (2011). Identity, language learning, and social change. Language Teaching, 44(4), 412-446.https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000309

Peirce, B. N. (1995). Social identity, investment, and language learning. TESOL Quarterly, 29(1), 9-31. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587803

Przymus, S. D. (2016). Imagining and moving beyond the ESL bubble: Facilitating communities of practice through the ELL Ambassadors Program. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 15(5), 265–279. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2016.1213133

Przymus, S. D., Lengeling, M. M., Mora-Pablo, I., & Serna-Gutiérrez., O. (2020). From DACA to Dark souls: MMORPGs as sanctuary, sites of language/identity development, and third-space translanguaging pedagogy for Los Otros dreamers. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 21(4), 248-264. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2020.1791711

Rezaei, S. (2017). Researching identity in language and education. In K. A. King, Y-J. Lai, & S. May (Eds.), Research methods in language and education (pp. 171-182). Springer.

Rezaei, S., Khatib, M., & Baleghizadeh, S. (2014). Language identity among Iranian English language learners: A nationwide survey. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 35(5), 527-536.https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2014.889140

Ryan, S. (2006). Language learning motivation within the context of globalization: An L2 self within an imagined global community. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 3(1), 23-45. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15427595cils0301_2

Simon, R. (1992). Teaching against the grain: Texts for a pedagogy of possibility. Bergin & Garvey.

Soltanian, N., & Ghapanchi, Z. (2021). Investment in language learning: an investigation of Iranian EFL learners’ perspectives. English Teaching & Learning, 45(3), 263-281. https://doi.org/10.1007/s42321-021-00089-z

Soltanian, N., Ghapanchi, Z., & Pishghadam, R. (2018). Investment in L2 learning among Iranian English language learners. Journal of Teaching Language Skills, 37(3), 131-168. https://doi.org/10.22099/jtls.2019.31876.2620

Soltanian, N., Ghapanchi, Z., & Pishghadam, R. (2020). Language learners’ imagined communities: Model and questionnaire development in the Iranian context. Applied Research on English Language, 9(2), 155-182.https://doi.org/10.22108/are.2019.115161.1418

Song, J. (2018). “She needs to be shy!”: Gender, culture, and nonparticipation among Saudi Arabian female students. TESOL Quarterly, 53(2), 405-429. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.488

Sung, C. C. M. (2019). Investments and identities across contexts: A case study of a Hong Kong undergraduate student’s L2 learning experiences. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 18(3), 190-203.https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2018.1552149

Tajeddin, Z., Mostafaei Alaei, M., & Moladoust, E. (2021). Learners’ perspectives on imagined community of practice in English as an international language. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development. 44(10), 893-907. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2021.1921784

Teng, M. F., & Bui, G. (2018). Thai university students studying in China: Identity, imagined communities, and communities of practice. Applied Linguistics Review, 11(2), 341-368. https://doi.org/10.1515/applirev-2017-0109

Trentman, E. (2013). Imagined communities and language learning during study abroad: Arabic learners in Egypt. Foreign Language Annals, 46(4), 545–564. https://doi.org/10.1111/flan.12054

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning, and identity. Cambridge University Press.

Wenger, E. (2010). Communities of practice and social learning systems: The career of a concept. In C. Blackmore (Ed.), Social learning systems and communities of practice (pp. 179–198). Springer.

Yoon, E., Adams, K., Clawson, A., Chang, H., Surya, S., & Jérémie-Brink, G. (2017). East Asian adolescents’ ethnic identity development and cultural integration: A qualitative investigation. Journal of Counseling Psychology, 64(1), 65-79. https://doi.org/10.1037/cou0000181