Competency-Based Education

Competency-based education (CBE) is surging in popularity as schools around the world scramble to implement their own versions of competency-based curricula (cf. Ash, 2012; Mulder, Eppin, & Akkermans, 2011; Nederstigt & Mulder, n.d.; Wong, 2008). What is behind this newfound popularity and what does it really mean for foreign language teachers, classrooms, and students?

Competency-based education has its roots firmly in the Behaviorist tradition popularized in the United States during the 1950s by educators such as Benjamin Bloom. CBE became popular in the U.S. during the 1970s where it was used in vocational training programs. The approach spread to Europe in the 1980sand by the 1990s, it was being used in Australia to measure professional-skills. Throughout its evolution, CBE has been known by a variety of names including performance-based learning, criterion-referenced learning, and capabilities-driven instruction (Bowden, 2004).

Because there is no conclusive evidence showing a link between knowledge about a subject and the ability to use that information in context, CBE expressly focuses on what learners can do rather than on what they know (Smith & Patterson, 1998). The basic idea is to focus on objective and observable outcomes which can be easily measured. CBE requires that students demonstrate value-added skills which are assessed by looking at outcomes rather than process (Bowden, 2004; Guskey, 2005).

Competency-Based Language Teaching

Competency-based language teaching (CBLT) is an application of the principles of CBE to a language setting (Richards & Rodgers, 2001). Its earliest applications were probably in adult survival-language programs for immigrants. By the 1990s, the approach had become so widely accepted in the U.S. that refugees wishing to receive federal assistance were required to attend some kind of competency-based ESL program to learn the skills necessary to function in society (Auerbach, 1986; Grognet & Crandall, 1982).

CBLT demands that language be connected to a social context rather than being taught in isolation. CBLT requires learners to demonstrate that they can use the language to communicate effectively (Paul, 2008;Richards & Rodgers, 2001;Wong, 2008). According to Docking (1994), CBLT:

…is designed not around the notion of subject knowledge but around the notion of competency. The focus moves from what students know about language to what they can do with it. The focus on competencies or learning outcomes underpins the curriculum framework and syllabus specification, teaching strategies, assessment and reporting. Instead of norm-referencing assessment, criterion-based assessment procedures are used in which learners are assessed according to how well they can perform on specific learning tasks. (p.16)

Competencies

A competency refers to "critical work functions" or tasks in a defined setting (Learning DesignsInc., 2011; Richards & Rogers, 2001).Successful completion of each specific task involves a set of skills and knowledge which must be accurately applied. In CBLT, a competency can be understood as the final task specified at the end of a learning module. For example, the Ministry of Education in Mexico (i.e., Secretaría de Educación Pública, SEP) identifies several competencies including “write notes to describe the components of different human body systems in a chart” , “understand and write instructions to face an environmental emergency”, and “express oral complaints about a health service” (SEP, 2011). These are the final tasks that each student is expected to do in order to have mastered the specified competencies.

In CBLT, students learn to use the language in authentic situations likely to be encountered outside the classroom. For instance, a student might have to fill out an application form, provide a personal medical history, or give directions on how to complete a specific task. Although students must practice in order to become competent, competencies are not practice activities. Competencies are not activities done for the sake of giving a student a grade,nor are they done only to allow a student to become better at a task. Competencies are practical applications of language in context.

Well-designed competencies include several components. First, they describe the specific knowledge and skills that can be applied to novel and complexsituations. Theknowledge and skills must have value beyond the classroom because if you teach the principles and how to learn, that knowledge will be useful for a student’s whole lifetime. For example, the ability to understand emergency instructions is important outside of the classroom and that knowledge will be useful for years in the future. Next, each competency must have clear performance criteria that allow students to know where they are and what they need to work on to improve. Each task requires its own specific rubric identifying specific weaknessesand strengths. Finally, the competency must be personalized (Sturgis, 2012). Poorly designed, non-explicit criteria and tasks will likely lead to probable failure since it would be difficult or even impossible to specify what needs to be done and to determine whether or not such competencies have been achieved.

CBLT requires a new approach to teaching, although not one that is necessarily new to most of the language educators(Online Learning Insights, 2012). Classes must be student-centered with a focus on what students can do. The ability to recite grammar rules or to identify errors in a written practice is not sufficient to measure competence. Students must demonstrate that they can accomplish specific tasks that are likely to be encountered in the real-world using the target-language.

Instead of being knowledge-focused, competency-based courses are built around the skills necessary to carry out specified tasks. Suppose the specific competency is to “make a telephone call to an office to complain about a service”.What skills would be needed to complete such a task? Several come immediately to mind, including:

- the ability to read and understand telephone numbers;

- the ability to identify oneself when answering or calling;

- the ability to ask to speak to someone;

- the ability to respond to a request to holdthe line;

- the ability to give a message or respond to an offer to take a message;

- the ability to express opinions politely following the target language conventional cultural norms;

- the ability to use past tenses; and

- the ability to provide relevant information.

In this example, daily lessons would be planned around information and activities that addressed these individual subcomponents. At each step along the way, students would receive information providing feedback about their individual progress toward mastering the competency.

Role of the Teacher

The role of the teacher changes from one of being an information-giver to that of a facilitator (Organization of American States, 2006; Sturgis & Patrick, 2010). This does not mean that teachers no longer give information, but that they give different types of information and deliver it in different ways. Teachers provide the materials, the activities, and the practice opportunities to their students (Paul, 2008). The quality and authenticity of these materials are central to the success of class.

Planning becomes a central part of the teaching process. First, each competency must be identified. Each competency must be subdivided into the relevant skills. Modules must then be developed which allow students the opportunity to learn and practice those skills. Teachers must determine exactly what and how well students must perform in order to master the competency. Specific rubrics assessing each competency must be developed and made public to the students from the beginning of the lesson (Auerbach, 1986; Richards & Rogers, 2001).

Teachers will have to devote large amounts of time to creating activities related to the specific skills necessary to fulfill the competency requirements. Significant time will also be required to assess students and provide specific, directed, and personalized feedback (Richards & Rogers, 2001).

Role of the Student

The role of the student must also change. Students will no longer be able to rely only on the teacher and the classroom to be the primary sources of information. Instead, students become apprentices. Their role will be to integrate, produce, and extend knowledge (Jones et al., 1994). Students take an active part in their own learning and work toward being autonomous learners. They learn to think critically and to adapt and transfer knowledge across a variety of settings. Because expectations and standards are clear and precise, students have to be committed to continuing to work on each competency, mastering it, and then progressing to another(Richards & Rogers, 2001; Sturgis, 2012).

Students may be resistant to this approach in the beginning, especially if they do not see any real need for learning the language. Successful classroom interaction depends on student participation. Students need to find ways to motivate themselves and find ways to apply information to their own lives and to integrate it into the classroom. Students must be willing to challenge, to question, and to initiate in the CBLT classroom (Marcellino, 2005).

Activities, Materials, and Syllabus

Although teachers are free to develop the strategies and tactics most likely to work in a given educational setting, the design of a CBLT syllabus is different from those of more traditional classes. Rather than being organized around specific language topics, CBLT courses are developed around competencies and the skills necessary for mastery. Each day and each unit focus on the skills necessary to move students along the path toward mastery. Syllabi must include performance activities that allow the student to practice the requisite skills (Griffith & Lim, 2010; Richards & Rogers, 2001; Wong, 2008).

This may require a shift in both thinking and organization. In many traditional classes, lessons are likely to be organized by topics such as present tense, past tense, irregular past tense, future tense with be going to, and so on. While these topics will still be taught, they will not drive the lesson nor will they be the focus. Instead, if a specific competency requires a student to use the past tense, then teachers will introduce that form and the vocabulary necessary for the specific task. The tense would be taught as an integral part of the lesson, along with relevant vocabulary, register, pronunciation, and so on. This suggests that, rather than being taught as a unit, the past tense may be introduced in multiple units depending on need. This allows modules to build on each other and students to practice skills learned earlier.

Class materials must be oriented to doing rather than knowing. There should be few exercises that require students to fill in the blank, circle the right answer, or specifically test only grammar. Rather, each task should be developed around a real-world situation requiring the use of some or all of the components of the specified competency. For example, if the competency is “giving personal information”, then tasks must require students to use knowledge about self to produce such information. Students mightpractice by creating a family tree, talking about favorite pastimes, or describing what they did over the weekend. Notice that the student is required to do something with the language (Richard & Rogers, 2001). Each of these activities requires the student to present knowledge about self.

The activities in the CBLT classroom must be oriented toward the ability to successfully complete a real-world task. The most effective materials will be authentic sample texts related to a specific competency (e.g., completed job applications; recordings of a complaint about a service). The materials help provide students with the essential skills, knowledge, attitudes, and behaviors required to meet the competency standards.

Assessments

Assessments can take one of two forms: formative or summative. Formative assessments are used to determine how well a student is progressing along the path to competency. Formative assessments must be frequent and specific. Because their goal is to assess progress and provide information about strengths and weaknesses, they are rarely graded. In CBE, the majority of assessments will be formative. Summative assessments, on the other hand, are designed to determine whether or not the student has mastered the competency. Therefore, summative assessments are typically administered at the end of each module as the final test. A student failing a summative assessment cannot move on to the next competency(Online Learning Insights, 2012; Richards & Rogers, 2001). Instead, the student must repeat the unit until mastery is achieved. Summative assessments are performance-based and may include a variety of measurement tools. Paper-and-pencil tests cannot be used to assess a competency except perhaps unless one is assessing a writing competency. True-false, fill-in-the-blank, and multiple choice tests are forever banished from the CBLT classroom as final competency assessments (Richards & Rogers, 2001; Sturgis, 2012; Sturgis & Patrick, 2010).

Assessments, like activities, must be authentic. Wiggins (1990) suggests that to be truly authentic, assessments must consider the task, the context, and the evaluation criteria. Authentic tasks require the use of knowledge and skills to complete a task. Similarly, authentic assessments require the measurement of real-world tasks. For instance, giving students a series of mathematics problems to solve on a test is not a good real world activity. Measuring how many correct answers a student got is not an authentic assessment. In the real world, who is randomly given a sheet with a series of math problems to solve for no reason other than getting a grade? On the other hand, asking students to figure out how much paint is required to paint a house, would be a good example. An assessment that determined whether or not the student had purchased the correct amount of paint for the job would be an authentic assessment that in fact measured the ability to complete the job.

For a language class, having students draw a poster or chart describing the human body and identifying the major systems (e.g., nervous system, digestive system) would not be a good real-world assessment choice. Very few people in the world would be required to draw such a chart simply for the purpose of drawing a chart. Having students describea medical problem would be a better choice. People are often required in daily life to provide a description of pain, where it hurts, what makes it hurt, and so on. It is clear that knowledge about the language (e.g., the parts of the human body, present tense) is required to complete the specific competency (i.e., explaining a medical problem to a doctor) but the assessment measures the ability to use that knowledge in context.

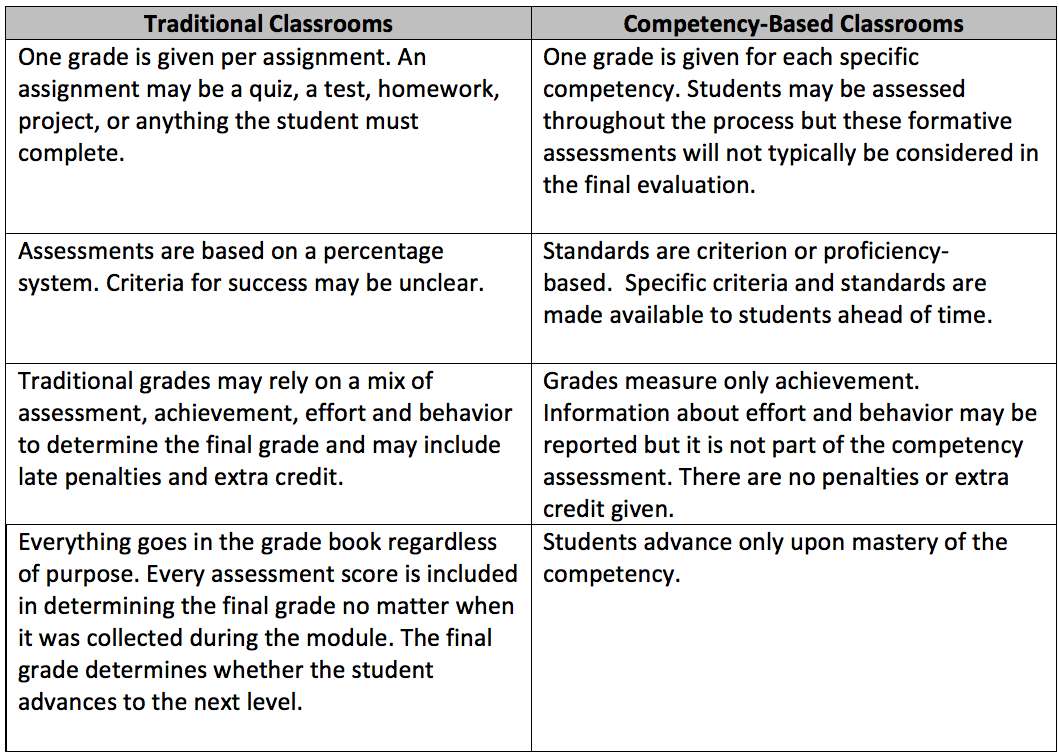

The followingtable, based on the work of O’Connor (2002), summarizes the differences between assessments and grades in traditional classes and those in competency-based classes.

Table 1: Traditional Versus Competency-Based Grading Style

Conclusion

In a competency-based curriculum, students are rewarded only for successful completion of authentic tasks. Ideally, at the beginning of a course, each student is given an initial assessment determining the level of proficiency. Students then proceed to learn the material, at their own pace, getting lots of informational feedback from the teachers. Students know, at every level of their work, where they are and what they need to do to meet the competency standards.

Some have criticized this approach saying it may be impossible or impractical to identify every necessary competency for specific situations (Richards & Rodgers, 2001; Tollefson, 1986). Supporters, however, argue that if students have clearly specified tasks and useful feedback, they are more likely to be able to learn to use the language in practical settings (Docking, 1994; Rylatt & Lohan, 1997).

Whatever your view, it is clear that competency-based education is more popular than ever. If it is to be successful, both students and teachers need to step out of their comfort zones and adopt new roles. In the short term, this unfamiliarity may create uncertainty and discomfort but as classes progress the benefits should become clear. If, however, students and teachers try to adopt a competency-based approach without making the necessary changes in their own behavior, the results are likely to be unsuccessful. On the other hand, if both embrace their new roles, they are likely to find learning becomes more effective and useful.

References

Ash, K. (2012). Competency-based schools embrace digital learning. Education Week, 6(1), 36-41. Retrieved 19 August 2014 from http://www.edweek.org/dd/articles/2012/10/17/01competency.h06.html

Auerbach, E. R. (1986). Competency-based ESL: One step forward or two steps back? TESOL Quarterly, 20(3), 411–415.

Bowden, J. A. (2004). Competency-based learning. In S. Stein & S. Farmer(Eds.), Connotative Learning: The Trainer’s Guide to Learning Theories and Their Practical Application to Training Design (pp. 91-100). Dubuque, IA: Kendall Hunt Publishing.

Docking, R. (1994). Competency-based curricula-The big picture. Prospect, 9(2), 8-17.

Griffith, W. I., & Lim, H.-Y. (2010). Making student-centered teaching work. MEXTESOL Journal, 34(1), 75-83.

Grognet, A. G., & Crandall, J. (1982). Competency-based curricula in adult ESL. ERIC/CLL New Bulletin, 6, 3-4.

Guskey, T. (2005). Mapping the road to proficiency. Educational Leadership, 63(3), 32-38.

Jones, B., Valdez, G., Nowakowski, J., & Rasmussen, C. (1994). Designing Learning and Technology for Educational Reform. Oak Brook, IL: North Central Regional Educational Laboratory.

Learning DesignsInc.(2011). Competency-based Training. Retrieved 19 August 2014from http://www.learningdesigns.com/Competency-based-training.shtml

Marcellino, M. (2005). Competency-based language instruction in speaking classes: Its theory and implementation in Indonesian contexts.Indonesian Journal of English Language Teaching, 1(1), 33-44.

Mulder, M., Eppink, H., & Akkermans, L. (2011). Competence-Based Education as an Innovation in East-Africa. Retrieved 19 August 2014from http://www.mmulder.nl/PDF%20files/2011-08-24%20Paper%20MM%20ECER%202011.pdf

Nederstigt, W., & Mulder, M. (n.d.). Competence Based Education in Indonesia: Evaluating the Matrix of Competence-Based Education in Indonesian Higher Education.Retrieved 19 August 2014from http://edepot.wur.nl/193715

O’Connor, K.(2002). How to Grade for Learning: Linking Grades to Standards (2nd Ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Corwin Press.

Online Learning Insights.(2012, June 12). The next big disruptor: Competency-based learning.[Web log comment]. Retrieved 19 August 2014fromhttp://onlinelearninginsights.wordpress.com/2012/06/12/the-next-big-disruptor-competency-based-learning/

Organization of American States.(2006). A coordinator’s guide to implementing competency-based education (CBE) in schools. OAS HemisphericProject on School Management and Educational Certification for Training and Accreditation of Labour and Key Competencies in Secondary Education. Retrieved 19 August 2014from http://www.moe.gov.tt/Docs/ICIU/CompetencyBasedEducation.pdf

Paul, G. (2008, December 16). Competency-Based Language Teaching Report. [Web log comment]. Retrieved 19 August 2014fromhttp://glendapaul62.blogspot.com/2008/12/competency-based-language-teaching.html

Richards, J., & Rodgers, T. (2001). Approaches and Methods in Language Teaching. New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Rylatt, A. & Lohan, K. (1997). Creating Training Miracles. Sydney: Prentice Hall.

Secretaría de Educación Pública. (2011). National English Program in Basic Education: Syllabus 2011, Cycle 4, 1st, 2nd and 3rd Grades Secondary School (Preliminary Version). Mexico City: Secretaría de Educación Pública.

Smith, J., &Patterson, F. (1998). PositivelyBilingual: Classroom Strategies to Promote the Achievement of Bilingual Learners. Nottingham: Nottingham Education Authority.

Sturgis, C. (2012). The art and science of designing competencies.Competency Works Issue Brief.Retrieved 19 August 2014from http://www.nmefoundation.org/getmedia/64ec132d-7d12-482d-938f-ce9c4b26a93b/CompetencyWors-IssueBrief-DesignCompetencies-Aug-2012

Sturgis, C., & Patrick, S. (2010). When Success is the only Option: Designing Competency-Based Pathways for Next Generation Learning. International Association for K-12 Online Learning. Retrieved 19 August 2014from http://www.inacol.org/cms/wp-content/uploads/2012/09/iNACOL_SuccessOnlyOptn.pdf

Tollefson, J. (1986). Functional competencies in the U.S. refugee program: Theoretical and practical problems. TESOL Quarterly, 20(4), 649–664.

Wiggins, G. (1990). The Case for Authentic Assessment. Practical Assessment, Research & Evaluation, 2(2). Retrieved 19 August 2014from http://pareonline.net/getvn.asp?v=2&n=2

Wong, R. M. H. (2008). Competency-based English teaching and learning: Investigating pre-service teachers of Chinese’s learning experience. Porta Linguarum 9, 179-198. Retrieved 19 August 2014from http://www.ugr.es/~portalin/articulos/PL_numero9/13%20Ruth%20Ming.pdf