Situating our Work within the Socio-historical Framework

In the study of English language programs research is frequently focused on test scores as representations of linguistic competence, on the phenomenological experiences of teachers and learners, on teacher training programs, and on the curricular development for successful programs. Due to the scarcity of educational programs in the area of Education Leadership, particularly for administrators of English Language Teaching (ELT) programs, most administrators in charge of institutes, university programs, and teacher education programs are self-taught. As a result, the voice of the language program administrator is rarely heard. In this study, we look at a particular type of administrator – leaders of state ELT programs at the primary school level in local contexts. Another factor that complicates the study of state administrators in Federal PNIEB programs is their position within unique instances in the state (Richards, 2000) Ministry of Education (Secretaría de Educación Pública – SEP) hierarchy. As a result, little research into ELT program administrators exists and even less that focuses on the experiences of state PNIEB administrators.

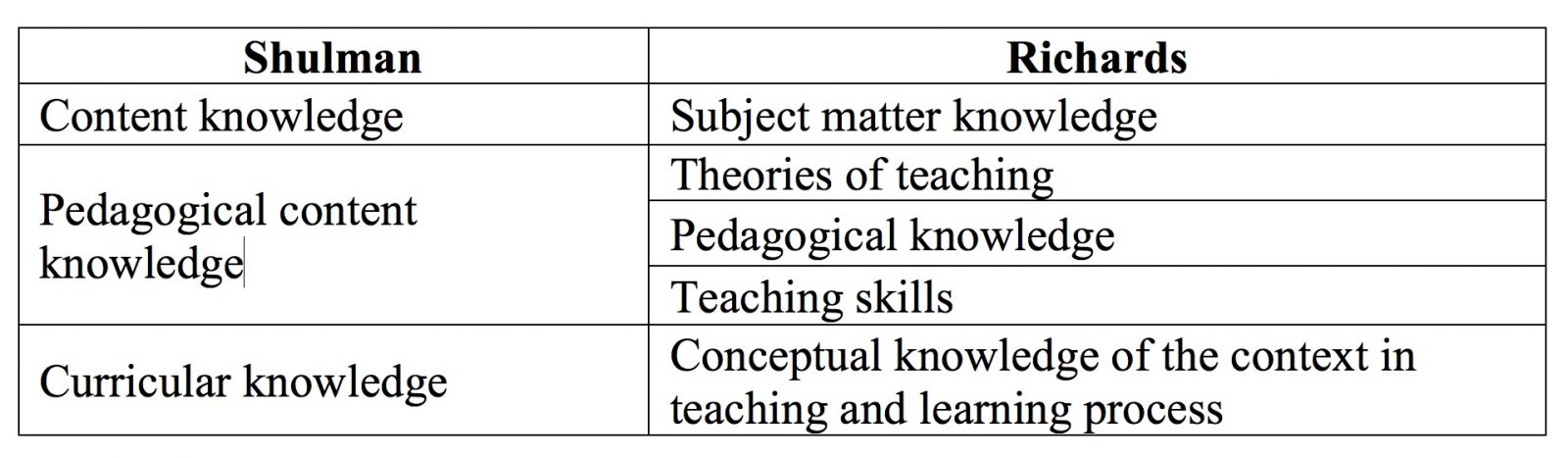

This article seeks to examine the feelings, views, and observations of one PNIEB program administrator through a teacher knowledge lens. In other words, based on the work of Shulman (1986) and Richards (2000), which describes what teachers should know, one administrator discusses the aspects of teacher knowledge as they saw them in the PNIEB program.

Pertinent Literature

Teacher knowledge

Up until the late 1980s, teacher performance was discussed and theorized in terms of teacher effectiveness. Teacher effectiveness referred to how good the teacher was at doing his or her job. It was not until Shulman’s 1986 address to the American Education Research Association (AERA) that teacher performance began to be examined in terms of teacher knowledge or what teachers need to know to do their job. Shulman distinguished between different types of content knowledge as that which grows in the minds of teachers; he suggested three types of knowledge: content knowledge, pedagogical content knowledge, and curricular knowledge. Shulman’s work provided a different way of looking at what teachers should know to be able to do their jobs. He described teacher knowledge in the following manner:

- Content knowledge refers to the subject area knowledge that the English as a Foreign Language (EFL) teacher possesses and how this knowledge is organized. Frequently this type of knowledge is referred to as linguistic competence and is broken down into knowledge of phonology, morphology, syntax, semantics, pragmatics, and discourse.

- Pedagogical content knowledge combines subject area knowledge with teaching skills or the knowledge of how to teach.

- Curricular knowledge is the understanding of how the subject area fits with the educational program in which it is taught.

This manner of looking at ‘good’ or ‘effective’ teaching is important because it served as a pre-cursor to Richards’ work that is described below. Whereas Shulman does not focus on any particular content area, other theorists began to put forth ideas that were specific to the teaching of English as a second or foreign language. One example that is pertinent to this study is the application of Shulman’s concepts to the area of second language teaching. This is our particular area of interest – foreign language teaching; Jack Richards (2000) put forth a similar and seemingly overlapping taxonomy of teacher knowledge in his Domains of Foreign Language teaching. These domains include theories of teaching or how teachers understand classroom practices, teaching skills, pedagogical reasoning, subject matter knowledge, and conceptual knowledge of the context in the teaching and learning process. In the authors’ estimation, Shulman and Richards’ taxonomies are related in the following manner:

From the late 1980s to 2000, there were many teacher educators that began to examine second and foreign language teaching and learning within multiple frameworks (Freeman & Richards 1996); (Freeman & Johnson 1998). The researchers in this study recognize the dynamic nature of language teacher education during that timeframe. We chose to use Richards’ taxonomy because of its particular appropriateness to our study. We chose a pedagogical framework because both of the researchers in this study recognize their socio-historical identity development defines them as teachers, not researchers. In part, they believe this is due to their lack of formal education in the area of teacher leadership and program administration.

Leadership models

Language program administration fits within a larger group of literature that focuses on the management literature (Pennington & Hoekje, 2010). As early as the 1980s, this field looked at leadership as the study of traits, styles, and skills of leaders. These traits usually include supervisory ability, which includes planning, organizing, directing, and controlling the work of others. A good leader is expected to balance his or her responsibility and desire for success with not trying to “do it all” and delegating tasks to others.

Leadership functions include decision-making and problem solving on a daily basis. Leaders are expected to be intelligent and self-assured, but a leader is not expected to be a genius and they must be careful that the self-assuredness required in their administrative role is not interpreted as egocentrism or obstinacy by the people they supervise in the program for which they are responsible (Pennington & Hoekje, 2010).

In short, there is no fixed definition of a good leader in general, much less a good leader in the area of English language programs. Program administrators in the public education sector are frequently people who have experience in education as teachers, or are recognized as exemplary teachers but are not trained administrators. Due to this lack of experience as administrators, there are tensions between the expectations of the program administrator and their constituents, such as the teachers, learners, parents and local school authorities. As we previously mentioned, most school leaders in Mexico are self-taught through their experience as administrators, particularly in the public sector. Those people who are recognized as exceptional or “born” leaders can be assigned administrative roles in educational programs, but the myriad of political factors that exist in the public system, oftentimes drive the challenges that school administrators face. These individuals frequently acquire administrative abilities and subsequently improve on their individual characteristics to become a good leader. This lack of definition of the position of administrator as well as the diversity of each individual PNIEB administrator’s educational and professional background leads to a dearth of cases on which to base an examination of the program administrator. As a result, this study looks at the work of a PNIEB program administrator; it does not seek to pronounce judgment on the leadership skills or traits of the program administrator, but seeks to provide insight into the particular experience of one PNIEB administrator.

Narrative Inquiry

The study of the experience as portrayed in a story is the essence of narrative inquiry (Connelly and Clandinin, 1990). Both the ways of knowing (epistemic) and the ways of being (ontological) are depicted through the co-construction of the participants’ stories in this type of research. Researchers have engaged in this type of research as a means of telling the story of the participants’ shared understandings from living in a particular community. In relation to this particular research, which is focused on ELT as the educational goal, we refer to the way Huber, Caine & Huber (2013) explained Clandinin’s and Connelly (1998) view of narrative inquiry as a means to remake life in classrooms, schools and beyond:

We see living an educated life as an ongoing process. People’s lives are composed over time: biographies or life stories are lived and told, retold and relived. For us, education is interwoven with living and with the possibility of retelling our life stories. As we think about our own lives and the lives of teachers and children with whom we engage, we see possibilities for growth and change. As we learn to tell, to listen and to respond to teachers’ and children’s stories, we imagine significant educational consequences for children and teachers in schools and for faculty members in universities through more mutual relations between schools and universities. No one, and no institution, would leave this imagined future unchanged. (p. 246)

This quote illustrates the researchers’ view of how narrative inquiry provides a venue for stories to provide insight into teaching and learning; in this case, the story evidences the administration of an educational program (PNIEB) that seeks to provide teaching and learning for young English learners in Mexico.

The narrative process is reflective; it allows us to have insights into how our participant’s life can shed light on a particular phenomenon. Narratives are accounts of social practice as co-constructed by the participants in the narrative. This methodology is best described by Koven (2012) where she explains “narrating event”. She refers to the interview or conversation, in this case electronically mediated through participation on the cloud site, as the place where the stories are told. In this case, data was gathered for this study through the use of an electronic dialogue journal.

The final story or the narrated speech event (Koven, 2012) is the story we present in this article. Although each of this article’s author-researchers have had experience in an administrative position in an English in Primary Schools program and these researchers have worked together and shared some academic decisions in a local ELT program in the past, the principal investigator (PI) no longer works with the PNIEB or in the SEP. The co-researcher who held the administrative position in the PNIEB program still works in the Ministry of Education in another capacity. The researchers both view the importance of putting forth the voice of this program administrator and as a result they agreed to work together to provide this story of leadership in a public school ELT program. The primary purpose of the study is to provide insight into one PNIEB administrator’s understanding of their work as program leader and decision maker as situated within their understanding of English language teaching.

Research design

To achieve our narrative goal, the researchers worked together in the manner that the following story tells:

Lucia and Amy met to discuss the importance of finding a way of putting forth Lucia’s voice as the program administrator in the local state program and how she worked to integrate the state program into a federally funded program when the time came. After extensive discussion a plan was developed and a means to implement this plan was designed. Lucia was particularly concerned that her thoughts and ideas be kept confidential because she still works in the Ministry of Education and because of the sensitive nature of the decisions she had to make as the program administrator. Amy suggested that perhaps the identities of the researchers could be kept confidential through the use of pseudonyms by the authors in the final publication. This idea was broached to the MEXTESOL Journal editors and accepted as a means of keeping the identities of the researchers, the state and the program confidential.

As theoretical framework, both researchers agreed that the study could be viewed through Richards’ (2000) taxonomy of teacher knowledge as explained in his teaching domains. They agreed to provide historical data regarding the development of these domains by mentioning Shulman’s (1986) work. Because Lucia and Amy live in distant geographic locations, it was agreed that Amy would post specific questions to an electronic journal for Lucia to answer. At this point, both researchers had equal opportunity to access the electronic journal and could contribute as they saw fit; Lucia chose to write a considerable manuscript that addressed her initial thoughts. This electronic document became the basis for further questions and answers in the dialogue journal. Over a period of several months, Lucia and Amy posted questions and responses to the electronic journal. This document then became the primary source of data for the construction of this narrative.

The unique manner of data collection described above in the previous story provides a clear picture of how the narrating event, as it is termed by Koven (2012), is a reflective process that is co-constructed by the researchers and participants in the narrative. Although narrative inquiry is frequently co-constructed between a researcher the participant(s) who provide the data that forms the story, this research study is different because of the professional and personal relationship of the researchers. One of the researchers, Amy, guided and directed the research design, data collection and analysis process, whereas Lucia provided the bulk of the description of the program administrator’s viewpoints, ideas, experiences and understandings of this experience. However, it should be noted that because of her experience in the public school system, Amy holds strong opinions about how the PNIEB program was developed from a local to state program. Notwithstanding, Amy worked to constantly bracket her personal experiences from the depiction of Lucia’s experiences. In her process of epoché (Patton, 2002), Amy became aware that her academic experiences as a program administrator for the state program allowed her a more complete understanding of Lucia’s struggle with the passage of the program from state to federal. As a result, although it is not Amy’s story that is being told in this narrative research, it is undeniable that as one of the researchers, Amy is a tool in the process of qualitative interpretative research.

After the data was collected and the researchers agreed that saturation was achieved, the electronic journal was uploaded as a data source to Nvivo for analysis. Nvivo is a qualitative research data analysis tool that is used to identify, save and later use themes and categories as they were presented by the participant(s) in the data. These themes were later used in the writing of the narrative. Amy was responsible for the in-depth examination of the text and the identification of themes. As previously mentioned, Richards’ domains of language teaching was used as a framework to categorize concepts and ideas expressed into the like concepts that are used as the basis for the narrative.

Lucia’s story

The narrative account has been separated into three segments: 1) Socio-historical background of public primary school English language teaching, 2) Teacher knowledge as outlined by Richards’ Domains and 3) State policy and political discourse on English language teaching.

Socio-historical background of public primary school English language teaching

Why English language instruction was implemented

In the late 1980’s, the Mexican government became concerned with its role in an increasingly globalized world. As a result, different states began to examine the teaching of English at the primary school level. In her reading, Lucia came upon this quote by Giddens (as cited in Block, 2008, p. 31) as a way to express her thoughts “the intensification of worldwide social relations which link distant localities in such a way that local happenings are shaped by events occurring many miles away and vice versa”. In other words, Lucia saw what was happening in the Mexican educational system as being impacted by things that were happening in other countries. The Mexican Government chose to respond to this educational need within ‘la Reforma Integral de la Educación Básica del 2009’ with the creation of the Programa Nacional de Inglés en Educación Básica (PNIEB). The government described the program’s goal as seeking to bring diverse social practices into the life of the primary school student through the use of English as a communicative language and to raise consciousness of other cultures. The local economy in the state where Lucia resides has been focused on small industry since the beginning of the 1980s when transnational industry moved to the area. As a result, English language learning became part of the local political discourse and policy as early as 1990. With that interest in mind, there were initiatives in different schools to provide English classes in some primary schools as early as 1995. These sporadic classes came to the attention of the SEP in approximately 1997 and in 2000 the Ministry of Education initiated a statewide English in Primary School Project.

How the state program became the federal program

Before 2009, it was federally mandated that students in Mexican public schools begin to study English at the secondary level in 7th grade. In spite of this curricular policy, some states had local English teaching initiatives that were funded by state governments. When the PNIEB program in Lucia’s state was still administrated by the local state government, management of the program was shared between the program director or administrator and the administrative offices, which were a part of the local state ministry. The number of schools and students that received English language classes was determined by the amount of money in the state budget that was allocated to the program each year. When the program began, classes started with first grade and each subsequent school year as the program grew, another grade level was added in the schools that had already established programs until students in grades one to six received English language classes in some of the state’s public schools. This strategy was continued in schools throughout Lucia’s state until 2009 with the integration of this state program into the Federal program. With the move to the Federal program, pre-school students began to study English.

In order to gain information about English language teaching in public primary students throughout the republic, federal authorities contacted states that had had local experience with the creation of an ELT program at primary level. At the same time, the Federal Government commissioned a group of people to design the PNIEB curriculum, as it is presently known. In order to become part of the federal initiative or PNIEB, the state English language teaching programs were requested to align themselves with the national program and implement the PNIEB curriculum locally.

For the state governments that had been fully responsible for the development and implementation of the local programs, the federal money that was infused into the state budget for the local English language teaching programs allowed them to count on a regular allocation to support the program. Previously, each state determined how many schools could be served at the state level based on the amount of money they had to invest in this program.

When the state program was morphed into a Federal program, the SEP determined the number of schools and students to be served in each of the states that adopted the federal ELT methodology, curriculum and teaching materials. When the individual states became part of the national program, they were asked to select a general coordinator who would be responsible for the overall administration and leadership of the local program.

Lucia was selected to be the Program Administrator for her local state PNIEB program. Because of her experience within the local state program, she became responsible for the financial decision making process; she had to make decisions regarding how the Federal resources were spent. Lucia was faced with managing the Federal budget, this time within the administrative procedures established by the local state system. Lucia explained that she had had no experience with managing the finances in the state program because previously, under the state system, the financial aspects of the program had been managed by one of the Administrative Departments within the state system. The fact that Lucia did not have to do this previously as the administrator of the state program made it even more challenging when she became administrator of the federal program.

Balancing teacher knowledge

Lucia’s challenges in balancing pedagogical and content knowledge

Some of the most challenging decisions Lucia was forced to make were those surrounding the ongoing education and training of teachers. The teacher candidates that applied for the teaching positions in Lucia’s state program came to her as the administrator – “the boss”-- with either pedagogical knowledge or subject area knowledge but rarely with both. In other words, they were either good teachers with sound teaching skills and methodology or they had strong English skills. After extended contemplation, Lucia had to decide which of these two aspects were more important. She decided that it would be easier teach the candidates with a good knowledge of the English language to teach than it would be to teach good teachers the English language. In other words, Lucia believed that teaching to teach would be easier than teaching English. From the beginning Lucia clearly saw the need for the state program and later on for the PNIEB teachers to possess both pedagogical knowledge and English language knowledge to be successful teachers.

Based on her decision to hire teachers with good skills English, Lucia worked extensively with well-known institutions to provide courses for her teachers that strengthened the teachers’ pedagogical knowledge focusing on specific topics such as lesson planning, classroom management and teaching materials. When there was not enough money in the budget to provide teacher training through specialized institutions outside of the state Ministry of Education, Lucia relied on her local teacher training team to development opportunities to focus on particular, specific aspects of teacher learning. More specifically, this meant that Lucia’s local team of teacher supervisors created and implemented courses that attended to the pedagogical aspect of teacher knowledge.

The development of teaching skills was of ongoing concern for Lucia in her role as program administrator but she was aware that her teachers needed curricular knowledge to be successful educators. In keeping with Richards’ definition of curriculum as the conceptual knowledge of the context in the teaching and learning process, she lamented that her teachers came to the program with knowledge of English, but not necessarily with the knowledge of how to teach curriculum within the local context. Lucia explained that one of the biggest challenges that needed to be address through teacher training was the fact that the classroom where the PNIEB teacher worked was arranged according to the needs of the Primary school teacher (maestro titular). In this classroom, the students became accustomed to the teaching routines and teaching methodology of the Spanish teacher. As a result, for the 50-minute English class, the teacher had to learn how to adapt to the local Spanish teaching context while not losing emphasis on the appropriate English language teaching methodology. Lucia explicated that in addition, the English teacher, because she or he is usually assigned to more than one grade or school, had to understand that it was their responsibility to interpret the contextual understanding of teaching and learning within the local setting at multiple sites. Lucia saw it as her responsibility to address this very complicated aspect of teacher learning in the professional development of her teachers. In the teacher training that she planned she had to provide methodologies for the teachers to be able to create socio-culturally authentic and natural learning environments that the PNIEB curriculum demands within the context of each individual primary school.

As the program grew, things became more complicated. Lucia was concerned when she explained how, because the local state programs aligned themselves with the pedagogical framework of the federal program, some of the more innovative instructional aspects of the local state programs were lost because of the federal guidelines.

Perhaps the most difficult moment for Lucia in the transition between the state and federal program was the downsizing of the number of teachers that had worked in her state in the first year of the program. This happened because the state had been able to hire more English teachers than the first year of the PNIEB program’s budget permitted. This decision was very difficult for Lucia to make because she knew that some teachers would lose their jobs and their only source of income. In addition, as program administrator, the understanding among the teachers was that Lucia could somehow prevent this from happening. She stated emotionally, “If I could have, I would have; but I couldn’t”.

English as a foreign language

Lucia recognized another contextual challenge: the students that her program serves are situated within a Spanish speaking world; the only opportunity for most of them to speak English in a real world, authentic manner is in the ELT classroom. Her resulting interrogative was, “Is it possible for the young learners to truly learn English if the instructional time is limited to 50 minutes three times a week?” This comment pointed to the limited instructional time that the student had to engage with the language. However, another unfortunate reality in the public school system is the limitations of the local system, she mentioned that one must take into consideration the days, hours or minutes that are shaved off of the classroom time due to events in the school, early dismissals, and practice for sports or school events or national or local holidays. She noted that this loss of pedagogical time is particularly alarming due to the limited time allocated to the teaching of English.

Localized teacher learning

Lucia described how she was able to work with the local university in the English teacher education process. As a result, she explained that in order for the pedagogical and professional demands of the program to be met, PNIEB teachers must be educated and trained in Mexico. Lucia believed that for the teaching professional to clearly understand the demands of the local context in terms of teaching and learning, they must have worked in this setting as practicing teachers. In designing university programs that seek to educate English teachers, both pedagogical and content knowledge must be emphasized in these areas of study. Opportunities for undergraduate and graduate TEFL programs to grow and flourish must be provided to meet the demands that this program will create as it grows and expands. Lucia called upon local authorities to improve one area of opportunity that she felt has not been appropriately addressed; the formation of teachers within the local normal schools in her and other states. She explained that in order to create a successful program, the future reality must be a true and complete articulation of all levels of education in the process of teaching and learning English. Lucia affirmed that the challenge in her state is and will continue to be that teachers must learn to create a learning environment that is, “as close to reality as possible so that students can experiment with natural language, just as they do with their native language” within the classroom.

Policy and political discourse

With the integration into the PNIEB program, it became clear to Lucia that there must be an eventual articulation between English language teaching curriculum between preschool, primary and secondary levels. This initiative represented a new way of thinking within the state system. Lucia explained that previously the teaching and learning of English as a Foreign Language had always been seen as unimportant; she stated that the Ministry of Education mostly ignored it. Lucia explained, “I don’t know why this happened. It could be attributed to the fact that there were no ‘experts’ in ELT within SEP, as a result, ‘English as a subject was considered unimportant, and secondary school teachers received little or no professional development.’”

The ELT program that Lucia described existed within a very political domain. Lucia clarified the state’s policy when she explained that “When any program is created and implemented under the auspices of one political party or another, the number of students and the number of schools served are credited to the party in power and serve to increase the party’s favor with its constituents.” In other words, an educational program that teaches English to young learners is extremely important in the political sense. Frequently, parents view English as a tool to be used in advanced studies as well as key for future success in obtaining employment (Sayer and Ban, this issue). Having access to English education is interpreted by parents as essential for their children and the political party that provides it would gain favor in the eyes of its constituents. As the English language teaching program grew within the state; the local party sought to tell its citizens that the program they had developed was the best in the country. Lucia observed that whereas the local government was willing to take credit for things they did correctly, even though they did not fully understanding the underlying theories and premises of the development and implementation of this program, they were unwilling to accept the needs and demands of a growing program such as this one. In her opinion, the Mexican government in many cases, authorizes the design and implementation of programs that they describe as “very interesting” yet these policies are in Lucia’s own words, “concentrated in spectacular documents” that remain inoperable because they are not founded in the real economic and sociocultural context of the country. Lucia explained that in most cases, the federal and local authorities do not want to situate themselves in the existing reality of the classrooms, the teachers and the students, but in the superficial aspects of any innovative program. Lucia emphasized these difficulties when she said that as a result of this governmental attitude, “it is very difficult to provide appropriate leadership in an environment such as this; an atmosphere of words with no meaning, and significant differences, that sometimes seem irreconcilable, between theory and practice, between concepts and actions.”

Sociocultural realities of Lucia’s state

Lucia also highlighted challenges that she knew she could not change. She observed that one question that local authorities were hesitant to accept and address in their political discourse was that of the severe inequalities that exist in public education within the municipalities of her state. More specifically, the individual physical plant and the technological resources of each school, the culture and the educational level of the parents in the primary schools were very diverse throughout the state. As a result, when the federal program mandated curricular policy such as the fact that classes had to be comprised of students of different ages and grades and language abilities, the challenges that Lucia reported in the PNIEB program become immeasurable for most teachers. With a question that has haunted program administrators throughout the world, Lucia exhorted, “Is it possible to standardize all aspects of academia? Can standardization of a particular program automatically extend to the standardization of the young student brains that the program is directed to instruct?” With these questions in mind Lucia considered the possibility that all young learners in Mexico could learn a foreign language with equal aptitude, even within the sociocultural challenges of the environment.

Another aspect of inequality that Lucia observed within her state, and all states in the Mexican Republic is the access to equal nutritional resources for the families of all students. She pointed to this factor as the subject of innumerable studies in Mexico and other countries, but she could only come to the unhappy conclusion that there is no nutritional equality in the world and it does in fact impact the learning of young minds. She underscored this as one more example of the lack of standardization or equality with the program.

Because Lucia participated in periodic meetings of PNIEB program administrators, she was able to observe that the adoption of a national English teaching policy served to open the door to a variety of questions throughout the republic, such as does the program consider the sociocultural factors such as the marginalization of different social groups, the vast differences in the socioeconomic context, the demographic aspects of determining where English classes should be offered: in urban, suburban or rural environment, and finally, the obvious need to consider the physical condition of the individual schools? She lamented that when the program puts for a “one size fits all” approach to English language teaching, with the same methodology and curriculum, they do not consider the students’ first language, be it Spanish or an indigenous language. Lucia’s acerbic words observed, “If only the PNIEB program were to provide magic wands along with the other teaching materials to address this type of pedagogical challenge!”

What needs to be done

Lucia believes that for the PNIEB program to be successful within the local context, people who have had a long trajectory in EFL teaching and are within the SEP system must support it. She characterized these ‘experts’ as people who must truly understand the “pedagogical practices, the teaching skills that teachers have, and the teaching context within which these teachers work.” Lucia emphasized that educational research into the ongoing development and implementation of an ELT program that meets local needs must be conducted in conjunction with local and external ‘experts’. Lucia was clear when she reiterated that the English program needed support from both local and external experts, each providing insight into how to maintain and develop the program; she opined that only this type of real information through collaboration between local and outside experts would enable the local Ministry of Education to provide a program of ongoing renovation for preschool, primary and secondary school students in her state.

Lucia’s Final Comments

First, Lucia exuded pride when she stated, “for me, it was an incredibly enriching experience to be part of a group of administrators that were chosen to lead the state programs and participate in the ongoing implementation of PNIEB at the state level.” Her pride included this strong patriotic observation, “it gave me enormous pride that my country [Mexico] had assumed the responsibility included within the implementation of such a program.” Although she did not say so with the intention of referring to the domains of second language teaching that Richards put forth, she defined the program’s mission as inclusive of all aspects of pedagogical knowledge, content knowledge and curricular knowledge.

Lucia pointed to the need for pedagogical knowledge when she explained that the strongest factor in determining the local training plan was the need for training in the area of pedagogy for the teachers in the PNIEB program. She saw the need for teaching methodology more pressing for the teachers because of her choice to hire teachers that had no background in pedagogy. As Lucia strove to find people who knew English to work as teachers, she accentuated her belief that content knowledge or English knowledge was more important than pedagogical knowledge. She saw pedagogy or English teaching methodology as more readily learnable than learning English. When Lucia sought to plan training that facilitated the English teachers’ work in the Spanish educational context and physical space, she was referring to the development of the teachers’ curricular knowledge. It was clear for Lucia as program administrator that her teachers needed to balance pedagogical content and curricular knowledge as described by Richards.

Finally, Lucia’s advice to the state government to consider the local sociocultural aspects of nutrition, learning abilities, and the physical conditions of the local schools underlined the socio-political aspects of the Mexican public school system that routinely served to challenge the work of her English teachers.

Conclusion

The purpose of this study is not to generalize findings to all PNIEB administrators. We put forth the story of this administrator to examine how her understanding of what teachers should know, or teacher knowledge, was one aspect of her life as the leader of a state program. Particular challenges that were highlighted were the lack of contextual understanding of the classrooms, student learning and the teaching of ELT by the Ministry of Education, therefore the promises that were offered were unrealistic in the world of English teaching. There was no middle ground to meet the financial realities and local needs to provide teacher training or teaching materials that were needed by the program. In spite of these struggles, this administrator spoke with pride about the strides her country took to meet the educational needs of young English language learners who live in an increasingly globalized society. She valued her experiences and the knowledge she obtained through her work. Her story puts forth evidence of how a program strives to offer its constituents something they had never had before: English language learning in public primary schools.

Particular lessons that could be learned from this administrator’s story could include the development of educational leadership or similar programs in local universities that include the teaching and learning of administrative skills and knowledge for the public sector. If this is not possible or will not happen until the universities are able to meet this need, then training should be provided to support the teachers who are forced into the role of program administrators at the state level. As the local state administrators meet periodically to discuss aspects of program development and implementation, perhaps that is an appropriate time to examine the challenges of directing a program in the public school system. Finally, administrators of local PNIEB programs should be invited to engage in ongoing reflection into the reasons for making pedagogic, content and curricular decisions.

References

Block, D. (2008). Language Policy and Political Issues in Education. In N. Hornberger, M. Stephen, N. H. Hornberger, & S. May (Eds.). New York, NY, USA: Springer.

Connelly, M., & Clandinin, J. (1990). Stories of Experience and Narrative Inquiry. Educational Researcher, 2-14.

Clandinin, D. J., & Connelly, F. M. (1998). Asking questions about telling stories. In C. Kridel (Ed.), Writing educational biography: Explorations in qualitative research (pp. 245–253). New York, NY: Garland Publishing.

Freeman, D., & Richards, J. (Eds.). (1996). Teacher Learning in Language Teaching. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Freeman, D., & Johnson, K. (1998). Reconceptualizing the Knowledge-base of Language Teacher Education. TESOL Quarterly, 32(3), 397-417.

Huber, J., Caine, V., & Huber, M. S. (2013). Narrative Inquiry as Pedagogy in Education: An Extraordinary Potential of Living, Telling, Retelling and Reliving Stories of Experience. Review of Research in Education, 212-242.

Koven, M. (2012). Speaker Roles in Personal Narratives. In J. A. Holstein, & J. F. Gubrium, Varieties of Narrative Analysis (pp. 151-176). Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE.

Patton, M. Q. (2002). Qualitative Research and Evaluation Methods (3rd ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA, USA: SAGE.

Pennington, M., & Hoekje, B. (2010). Language Program Leadership in a Changing World: An Ecological Model. Binglley, UK: Emerald.

Richards, J. C. (2000). Beyond Training: perspectives on language teacher education. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Shulman, L. S. (1986). Those who understand: knowledge growth in teaching. Educational Researcher, 15(2), 4-14.