Introduction

Listening, reading, speaking, and writing are essential skills to develop when learning a second or foreign language. However, another ability is as crucial as the four others: vocabulary (Mehring, 2006). Despite its importance in language learning, vocabulary skills are frequently overlooked in language learning. The ability to acquire a second/foreign language requires vocabulary knowledge, and a lack of vocabulary knowledge is a barrier to learning a language. Vocabulary mastery is an important component of the four language abilities, and it should be considered one of the required components of language.

In Today's 21st-century classrooms, digital technology must coexist with traditional tools (Hassan & Hashim, 2021). Folse (2004) suggested that if vocabulary lists were utilized in moderation to learn L2, they could be effective tools for learning new words. It has been shown to improve students' vocabulary skills (Hung, 2015; Yamamoto, 2014). On the other hand, considerable research has concluded that vocabulary lists are ineffective and inefficient for learning (Pennington, 2015), since they do not indicate how the words are used in context (Harmer, 1991). Another tool that has gained popularity in recent years is using an online interactive response system, such as Socrative. This software has been implemented in English classrooms to assist students in improving their vocabulary learning (Alharbi & Meccawy, 2020; Pham, 2018). This platform is capable of delivering quizzes with intriguing animations. As a result, it has been used to increase student engagement (Dakka, 2015; Lim, 2017).

Literature Review

Importance of vocabulary skills

Vocabulary is a significant aspect of language learning, being considered just as crucial as the primary language skills of reading, writing, listening, and speaking (Mehring, 2006). An essential aspect of learning a foreign language is the development of vocabulary because the meanings of new vocabulary are significantly emphasized (Alqahtani, 2015). Nonetheless, vocabulary acquisition is often ignored. (Cetinkaya & Sutcu, 2019). Therefore, there is an urgent need to thoughtfully integrate vocabulary in foreign language learning (Folse, 2004). Students need encouragement to have a good command of vocabulary and language use. According to several studies, a considerable amount of vocabulary is necessary for learners to function effectively in the four language skills of listening, speaking, reading, and writing (Subon, 2013). Learners should be able to use at least 2000 high-frequency words in order to function fairly well in the second language. Most researchers suggest a minimum vocabulary of at least 3000 families of words (Thornbury, 2002).

Vocabulary lists

Lists of vocabulary words are commonly used in many English as a Foreign Language (EFL) contexts (Folse, 2004). A common practice among L2 learners is the use of word cards or vocabulary lists to actively learn lexical subjects and meanings, either on a piece of paper or a series of double-sided cards (Hung, 2015). In Asian contexts, most teachers and students use vocabulary lists in teaching and learning English vocabulary (Lessard-Clouston, 2013). There are several different teaching resources that a teacher can use to reinforce the chances of success for their students by offering frequent access to vocabulary items, e.g., in a reading passage or a vocabulary list in the English textbook that the students see at the back of each unit (Wilcox & Morrison, 2013). According to direct acquisition studies, dictionaries and vocabulary lists, which put the learners' attention into immediate contact with the form and meaning of words, can be utilized to learn vocabulary.

Meara (1995) believed that using vocabulary lists in acquiring L2 vocabulary was one of the most efficient methods. Vocabulary lists are useful for assisting students in focusing on structure and context for repeated retrieval (Hung, 2015). Thornbury (2002) pointed out that the importance of learning vocabulary through vocabulary lists may have been underestimated, and numerous approaches for using vocabulary lists in the classroom were proposed. Vocabulary retention is much higher than that of article reading, according to the study on this topic (Lu, 2004). Similarly, research studies in different countries have indicated that using vocabulary lists has increased vocabulary retention significantly more than contextualized vocabulary learning (Laufer & Shmueli, 1997; Qian, 1996). Yamamoto (2014) examined how EFL Japanese university students used vocabulary lists in their out-of-class vocabulary learning and found that their use contributed to vocabulary development. Along with their vocabulary list self-study, the students reported using and integrating a variety of learning strategies, the most essential of which were memorization and repetition. They would repeatedly look at, write down, or read aloud the words to improve their rote learning of vocabulary items. Furthermore, the students' learning outcomes were positive, as they improved both their receptive and productive vocabulary sizes.

Some researchers, on the other hand, believe that learners need to acquire words in meaningful situations. In his article, Pennington (2011) argued that not all vocabulary instruction in the classrooms is effective or efficient. For instance, weekly vocabulary lists assigned to students to learn and later be assessed are ineffective and inefficient. Harmer (1991) stated that memorizing the lists of words was one of the most traditional methods for learning vocabulary. Although there are some benefits of using this method, it does not necessarily mean that learners learn these words completely. Learners do not only need to know what words mean, but also they need to know how the words are used in context. Shen (2003) argued that the contextual and consolidating (2C) dimensions and dynamics of acquiring vocabulary should be explored.

Socrative and vocabulary skills

Socrative is a technology-based tool that offers many features to create tasks, such as question-giving and answering-receiving tasks (Méndez-Coca & Slisko, 2013). It is an intelligent student response device that allows teachers to discover or analyze what students have learned in real-time (Kaya & Balta, 2016). Teachers can create and give students a simple quiz using Socrative and set time limits. Socrative also allows short answer questions, but teachers have to check them manually. After a quiz session, teachers receive a report that shows each student's answers for each question and their total points. Hence, teachers can monitor the extent of students' understanding of the material they are learning. Lim (2017) reported that students had a positive learning experience with using Socrative.

Socrative has been used to improve vocabulary skills in several studies. Nurhasanah (2020) did a study to see if it could be used to teach high school students vocabulary, and found a substantial difference between the treatment and control groups. The group that used Socrative got better results than the group that did not. Another study also found that the platform was positively perceived by students, and they recognized that it improved their vocabulary skills (Widyastuti, 2016). Yarahmadzehi and Goodarzi (2020) investigated the effect of Socrative on pre-intermediate students’ vocabulary skills and found a significant improvement. The platform was also utilized to teach vocabulary, particularly phrasal verbs, to higher English proficiency level students, CEFR B2, C1, and C2. The study reported students’ positive attitudes towards the use of Socrative (Vurdien, 2021) and also stated that the site could be viewed as a dependable instructional tool for improving language acquisition. In addition to students’ positive attitudes and perceptions and improved learning achievement, Socrative was also reported to give teachers and students more autonomy in their teaching and learning of English vocabulary (Velayutham et al., 2017).

Though benefits were reported, several issues with the platform were found. Rofiah and Waluyo (2020) studied the limitations of Socrative when it was used to give vocabulary tests and reported that most students found it easy to cheat during Socrative tests. Students also preferred doing the vocabulary test using Socrative on paper because it made it more convenient for them to cheat. Similar cases were found in other studies (Florenthal, 2018; Saraçoğlu & Kocabatmaz, 2019) where Socrative was used.

Research questions

It is interesting to observe how vocabulary lists and interactive response systems can complement each other to assist students in learning vocabulary. The vocabulary lists can be used as an independent learning assignment, while the quiz can be used to practice using the words in context. Hence, the objectives of this research study are as follows.

- How do vocabulary lists and Socrative affect students’ vocabulary skills?

- How do students perceive the use of vocabulary lists?

- How do students perceive the use of Socrative?

Method

Research Design

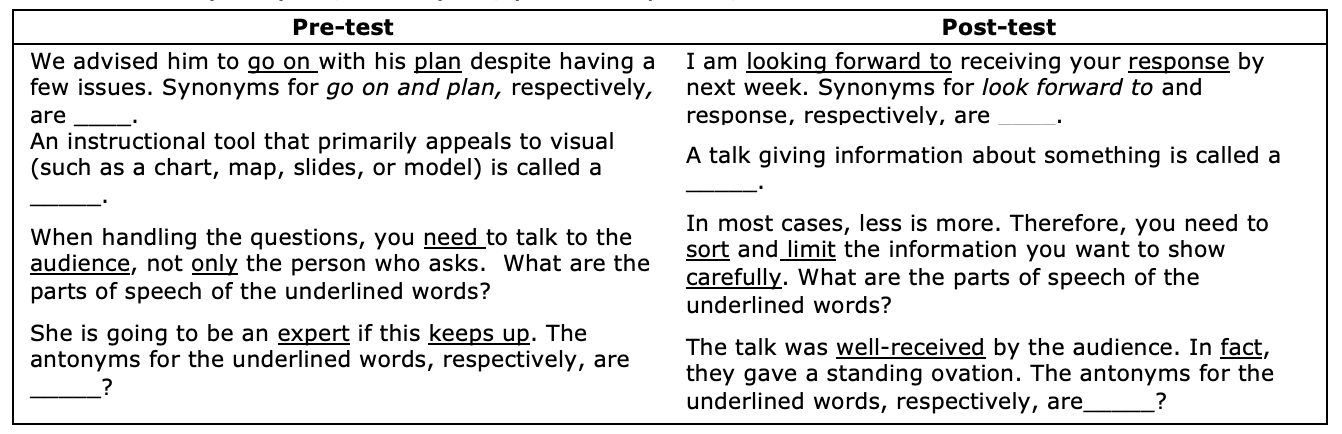

To investigate how vocabulary lists and Socrative affect students’ vocabulary skills, this study utilized a mixed-method research design which combines collection and analysis of both quantitative and qualitative data. The first research question (RQ) was answered by gathering and analyzing quantitative data while the second and third heavily relied on qualitative data. To answer RQ 1, this study compared the scores of students’ vocabulary pre-test and post-test. Three TEFL specialists analyzed and evaluated both the pre-test and post-test for quality and comparability. Each test contained 20 vocabulary questions. The vocabulary questions consisted of synonyms, antonyms, parts of speech, and definitions.

Table 1: Sample questions in the vocabulary quiz

To answer RQ 2 and 3, focused group discussions and in-depth interviews were chosen to answer the second question. There were only two sessions of focused group discussions due to the conflicting schedules of volunteering students, but several in-depth interviews were done face-to-face and others were done via voice call. Both focused-group discussion and in-depth interviews were semi-structured.

Participants

This study was conducted at Walailak University, Thailand, during the Academic Year of 2018-2019 and used convenience sampling. The participants consisted of 189 first-year students from various majors (144 females and 45 males) taking a General English course entitled English Presentation in Sciences and Technology (GEN61-127) offered by the School of Languages and General Education, Walailak University, Thailand . Their age ranged from 18 to 20 years old. Their English proficiency level tests indicated that 50 students were in level A1; 41 were in level A2; 50 were in level B1; 48 were in level B2. Before the study began, all participants were given a written consent form.

Course design

The highlighted subject in this study was the General English (GE) course described above. Based on the course description given in the TQF (Thai Qualifications Framework) for Higher Education form, this course focuses on developing the four essential English skills: listening, speaking, reading and writing while emphasizing essential expressions, structures and English vocabulary specific to the scientific presentation. It also equips students with the necessary skills for effective presentation with ICT integration inside and outside the classroom.

A pre-test was conducted in the first week of the term before lectures were delivered. The lectures started on Week 2 and were completed by Week 11. Meanwhile, students were assigned to complete writing the sentence examples for 50 words mentioned in the vocabulary lists weekly. There were ten sets of vocabulary lists for the students to complete before the in-class vocabulary tests in the textbook. Each week students did one vocabulary quiz using Socrative from Week 2 to Week 11 (10 weeks). Every week before the class started, students took the in-class vocabulary test using Socrative. They took the vocabulary post-test at the end of the term (Week 13).

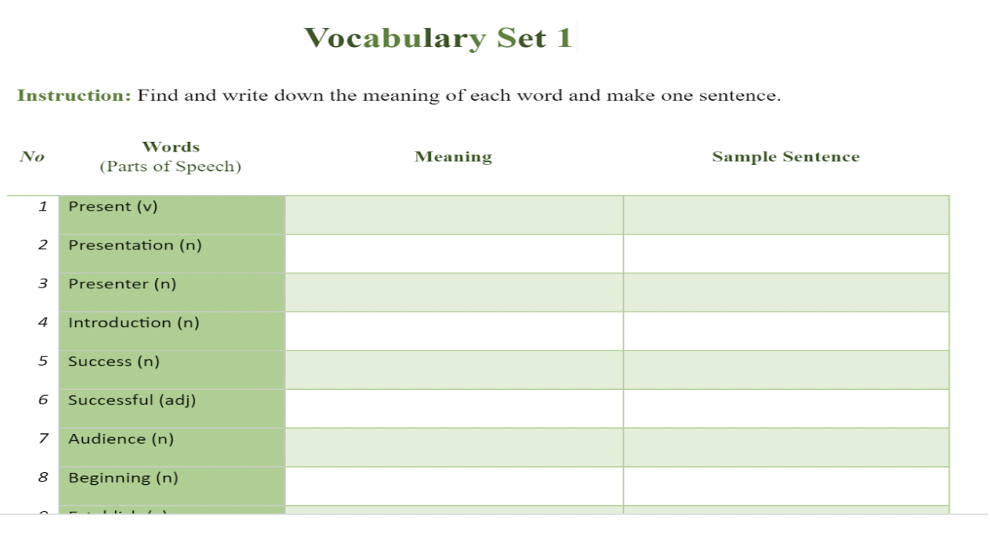

Vocabulary list

Ten vocabulary sets consisted of 500 words and were made based on the coursebook. Each set had 50 words of A2-B2 CEFR levels. Students were assigned to find the definition of each word and write a sample sentence. They were expected to have learned the words before the in-class quiz (Sanaoi, 1995). Figure 1 and Table 1 are examples of the vocabulary sets.

Figure 1: Example of the vocabulary set in the textbook used in this study

Table 2: Sample of weekly vocabulary list

Preparation

Each quiz was made based on a vocabulary set. There were 10 to 15 words chosen per set. The gamified quiz using Socrative was administered in the first 15 minutes of the class. Students were given a context or a sentence and were asked to identify the meaning, synonym, antonym, or parts of speech.

In-class application

The teacher ran the quiz by clicking "launch" and selected the available adjustments, as shown in Figures 2 and 3. In this study, the quizzes were run in the instant feedback mode. This mode enables the delivery of immediate feedback, which is beneficial for students learning (Brookhart, 2017). Students would be notified whether their answers were correct or wrong before moving on to the next question. While the students were working on the quiz, the teacher observed the live result table.

Figure 2: Launching a quiz

Figure 3: Real-time observation of students' progress and results

After the lesson

The teacher could access a comprehensive report consisting of the whole class or individual student's results as part of a reflection to decide who needed more guidance. Reflection is essential for improving the educational process (Fendler, 2003). Students who scored less than 60% on each test were provided further consultation or lessons at the teacher's office in this study.

Figure 4: Accessing the report

Data analysis

The pre-test and post-test quantitative data were examined using descriptive and inferential statistics to answer the first research question. The effect of the treatment on students' vocabulary skills was investigated using a paired-samples t-test. In addition, the students' pre-test and post-test scores were compared to their CEFR levels. This analysis was done to provide more detailed results.

The acquired qualitative data were subjected to content analysis (Hsieh & Shannon, 2005) and categorized according to the themes developed from the analysis to answer the second research question. The data obtained from the focus groups and in-depth interviews complemented each other and led to a thorough analysis.

Research Results

Effect of vocabulary lists and Socrative on students’ vocabulary skills

The paired-sample t-test demonstrated a significant difference between the pre-test and post-test scores of students (t(188)=-19.86), p < 0.00. The mean of post-test (M = 14.22, SD = 4.37) was significantly higher than pre-test (M = 9.43, SD = 2.64) by 4.79. This implies that the effectiveness of the treatment to improve students' vocabulary was high.

Table 3: Paired samples statistics

![]()

Table 4: Paired samples correlations

To investigate further, the students’ pre-test and post-test scores were compared based on their CEFR levels as indicated in their English proficiency test results. Table 3 shows that the pretest scores of each group are lower than posttest. The A1 group’s mean difference was 4.38; The A2 was 5.26; The B1 was 3.08; The B2 was 6.56. The numbers indicate the improvement in the vocabulary skills of each group. Students in levels B2 and A2 showed bigger improvement than those in B1 and A1. Meanwhile, the difference between A1 and A2 was not far; that of B1 and B2 was noticeable.

Table 5: Descriptives – CEFR levels

Students’ perceptions of vocabulary lists

From the results of the focused group and in-depth interviews, students' perceptions of vocabulary lists were sorted into two groups, namely benefits and drawbacks.

Benefits of vocabulary lists

There were several benefits of vocabulary lists conveyed by the students. One was preparing them for the upcoming Socrative tests. Students from four CEFR levels, A1, A2, B1, and B2, agreed that completing the vocabulary lists before the tests helped them prepare better for the tests. An A2 student stated, “I think my score is high because I completed the vocabulary list.” A B1 student commented, “One time I was very busy and did not complete the vocabulary list, and my Socrative test score was low.” Another benefit was learning new vocabulary. All students from all levels agreed that they learned new words and how to use them in sentences by completing the vocabulary lists. A B2 student said, “The vocabulary set makes me learn new vocabulary every week.” Another student (B1) stated, “There are new words in the list, so I have to search on Google and find their meaning. Then, I can make sentences.” The next benefit was memory retention. Students revealed that looking for each word’s meaning and creating a sentence with the word helped them memorize the vocabulary for a long time. A student (B1) commented, “I did everything by myself, including the sentences. I still remember most of the words.” Another student (A2) revealed, “It makes me practice using the words. It helps me remember more.” The other benefit was knowing the parts of speech of the words. The majority of A1 and A2 students expressed that they did not know much about parts of speech before. The B1 and B2 mentioned that they knew about them, but did not know parts of speech of all vocabulary words, so they still had to learn some of them. Since it is a part of the test, they had to familiarize themselves with the parts of speech. Since the vocabulary lists show the parts of speech of each word, it was beneficial. A student (B1) mentioned, “Sometimes there is one word with more than one part of speech, and the meaning is different. That is why it is important to learn if it is a noun or verb or others.” Another interviewee (A1) said, “The vocabulary list is very easy to use. I can see them there easily.”

Drawbacks of vocabulary lists

Students conveyed several drawbacks of the vocabulary lists. The B1 and B2 students were concerned about the format. They mentioned that the spaces were not big enough, so they wrote only simple sentences. They revealed that they would practice more if the columns were bigger. A student said, “I hope the teacher enlarges the columns in the future because I want to write more.” Another drawback is related to the amount of homework. Students revealed that they received assignments from all courses and that they were overwhelmed. The vocabulary lists added to their workload at home and sometimes stressed them out. An A1 student mentioned, “I have a lot of homework, teacher. It (vocabulary list) gives me a headache.” A B1 student conveyed that he requested the instructor to reduce the number of words assigned to him. Several students agreed with him and mentioned that 20 or 10 words a week was a more appropriate assignment. The next drawback was the students’ indifference. Several students from all CEFR levels confirmed that some of the friends copied others’ work in the in-depth interviews. They also simply rewrote sentences from the internet instead of making their own. An A1 student mentioned, “a person sometimes copies homework because they are lazy.” A B2 student revealed, “some of my friends do the vocabulary list one hour before the class in front of the classroom. They also usually copy their friends’ homework.”

Students’ perceptions of Socrative

Students’ perceptions were sorted into two groups, benefits and drawbacks.

Benefits of Socrative

Most of the students' responses were related to accomplishment. They agreed that Socrative helped them practice some words they had previously studied at home. An A2 student said, “It is not easy, but I learn words little by little every week. Thanks, Socrative.” A B1 student mentioned, “The weekly tests are good and help me learn more vocabulary”. A B2 stated, “There are some words that I already knew, but I learned that those words have more than one part of speech.” The second category is convenience. The students from all CEFR levels expressed that using Socrative was convenient, user-friendly and, most importantly free. An A1 student stated, “It is very easy. I can use it on my phone.” An A2 student shared, “My smartphone is old, but I can use Socrative.” In the in-depth interview, a B2 student said that she can access the platform very easily as long as the internet connection is strong. The final category was engagement. Several students conveyed that the use of Socrative made them awake, more engaged, and ready for the lesson. A few discussed the timing for the Socrative test. They pointed out that putting it in the first 15 minutes of the lesson was the right choice because it would encourage them not to come late to class and be ready for the lesson. A B1 student said that when the teacher used the Space Race Mode, it was very engaging.

Drawbacks of Socrative

Students mentioned several issues with Socrative. The major one was cheating. Several students (A1, B1, B2) stated in in-depth interviews that they felt it was sometimes unfair. Their classmates who did not prepare at home before the test got good results because they could use other applications to help them find answers. A student (B1) also revealed that several individuals would share their answers with their friends via messaging apps. Even though the questions and answers were randomized, by sharing screenshots, they were able to help each other. An A2 student confessed that she cheated one day during Socrative tests because she was not prepared and felt scared she would get a low score. Another problem was the internet connection. Several students relied on the university wi-fi. Nonetheless, the connection was sometimes unstable or slow. They stated that it affected their ability to access Socrative. An A2 student said, “I have to borrow my friend’s phone after he finishes.” A B1 student mentioned, “I once got 8 out of 15 because my internet connection was bad and I could not finish the test on time.” Several students also discussed getting their own internet data packages. Nonetheless, mixed reactions were observed. Several agreed and others disagreed. A B1 student said, “I think the university must improve the wi-fi.” An A2 student shared,” I am okay buying my own internet because I also use it outside the class.”

Discussion

The results of this study showed that using a vocabulary list and Socrative to improve students' vocabulary skills might be effective. To some extent, this study supported the finding of Yamamoto (2014) that using vocabulary lists is effective to improve students’ vocabulary skills. This finding also corroborated Meara (1995) that vocabulary lists are one of the most effective ways to learn L2. Since the participants of this study confirmed that doing the vocabulary list helped them learn the meaning, parts of speech, and how to use the words in sentences, this study also supported the finding of Hung (2015) that learners can use vocabulary lists to help them focus on structure and context for repeated retrieval. Moreover, in relation to memory retention, it was found that the vocabulary list helped students to remember the words more and prepared them for the tests. This finding was congruent with that of Lu (2004), who reported that the vocabulary list helps vocabulary retention. The vocabulary list used in this study enabled students to look for the meaning of each word by themselves and practice using the word in context by writing a sentence. As students mentioned, creating new sentences using the words assisted their memory retention.

In relation to Socrative, this study supported the findings of previous studies (Nurhasanah, 2020; Yarahmadzehi & Goodarzi, 2020) that the platform positively affects students’ learning achievement. The finding of this study was also congruent with those of Widyastuti (2016) and Vurdien (2021) that students positively perceive the utilization of Socrative. Although Socrative can benefit vocabulary learning, it was found that it also can increase the risk of cheating. This finding was in line with that of Florenthal (2018), Rofiah and Waluyo (2020), and Saraçoğlu and Kocabatmaz (2019). This study found that students cheated by opening translating, browsing, and messaging apps while doing the tests.

In relation to students’ CEFR levels, the treatment used in this study which combined vocabulary list and Socrativemight significantly improve the vocabulary skills of students from all English proficiency groups. This shows that the treatment benefits students of different CEFR levels. Also, in relation to their perspectives, students’ perceptions from various CEFR levels were not significantly different. The students in the focused group discussions and in-depth interviews mostly revealed similar themes. This study demonstrated that the majority of students at all CEFR levels have positive perceptions toward the treatment. This finding is congruent with that of Vurdien (2021) that students with higher CEFR levels have positive perceptions towards vocabulary learning with Socrative. Also, it supported that of Yarahmadzehi and Goodarzi (2020) that students with pre-intermediate English proficiency levels have positive attitudes towards vocabulary learning with Socrative.

Conclusions

Vocabulary is an essential element in language learning, including English. Therefore, it is crucial to promote vocabulary learning by utilizing effective methods. This study has coroborated that the utilization of vocabulary lists and Socrative could effectively enhance the vocabulary learning of students at various CEFR levels, A1, A2, B1, and B2. By working with the vocabulary lists, students can learn several words independently. This study suggests that by asking students to remember the words and make and write sentences using those words, they were able to practice using the vocabulary in context and remember the words longer. By providing an engaging and convenient platform for vocabulary practice during class, Socrative improved memory retention even further. Therefore, the two tools were a successful pair to improve students' vocabulary learning with various CEFR levels.

Nevertheless, there are several implications from the reported drawbacks. Concerning the vocabulary lists, instructors need to ensure that students have sufficient space to write longer sentences in the list and that students do not simply copy their peer’s work. Furthermore, students’ vocabulary lists must be closely checked in order to avoid cheating since it is a significant issue with Socrative. Students can easily open dictionaries using their phones during tests. Hence, teachers must proctor each student during the test and give a proper time limit.

Even though this study was conducted in a university in Thailand, a similar intervention can be beneficial in other EFL contexts where similar challenges occur. However, there were several limitations of this study which open opportunities for future research. Although this study included students with different English proficiency levels, there was an absence of advanced English learners or those in CEFR levels C1 and C2. It didn’t represent all levels of EFL learners. Thus, further studies could focus on investigating how these two tools affect the students at the C1 and C2 levels (proficient users). It would also be advisable to investigate the utilization of weekly vocabulary lists and Socrativeusinga quantitative approach to see a different perspective. Although the current study had several limitations, the findings could be beneficial for language teachers to develop and discover tools that add values to teaching and learning in designing course learning materials and assessments. Also, it is suggested to encourage students to use different types of conventional and technological learning tools. As a result, traditional tools can still coexist with modern technology-based learning tools.

References

Alharbi, A. S., & Meccawy, Z. (2020). Introducing Socrative as a tool for formative assessment in Saudi EFL classrooms. Arab World English Journal, 11(3), 372-384. https://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol11no3.23

Alqahtani, M. (2015). The importance of vocabulary in language learning and how to be taught. International Journal of Teaching and Education, 3(3), 21-34. https://doi.org/10.52950/TE.2015.3.3.002

Brookhart, S. M. (2017). How to give effective feedback to your students. ASCD.

Cetinkaya, L., & Sutcu, S. S. (2019). Students’ success in English vocabulary acquisition through multimedia annotations sent via WhatsApp. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 20(4), 85-98. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.640517

Dakka, S. M. (2015). Using Socrative to enhance in-class student engagement and collaboration. International Journal on Integrating Technology in Education, 4(3), 13-19. http://dx.doi.org/10.5121/ijite.2015.4302

Fendler, L. (2003). Teacher reflection in a hall of mirrors: Historical influences and political reverberations. Educational Researcher, 32(3), 16-25. http://dx.doi.org/10.3102/0013189X032003016

Folse, K.S. (2004). Vocabulary myths: Applying second language research to classroom teaching. University of Michigan Press.

Florenthal, B. (2018). Student perceptions of and satisfaction with mobile polling technology: An exploratory study. Journal for Advancement of Marketing Education, 26(2), 44-57. https://www.mmaglobal.org/_files/ugd/3968ca_7abac5a9adfa4e1886b0f3b4dc65b0d6.pdf

Harmer, J. (1991). The Practice of English language teaching. Longman.

Hsieh, H.-F., & Shannon, S. E. (2005). Three approaches to qualitative content analysis. Qualitative Health Research, 15(9), 1277–1288. https://doi.org/10.1177/1049732305276687

Hung, H.-T. (2015). Flipping the classroom for English language learners to foster active learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 28(1), 81-96. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2014.967701

Kaya, A., & Balta, N. (2016). Taking advantages of technologies: Using the Socrative in English language teaching classes. International Journal of Social Sciences & Educational Studies, 2(3), 4-12. https://ijsses.tiu.edu.iq/wp-content/uploads/2017/12/Taking-Advantages-of-Technologies-Using-the-Socrative-in-English-Language-Teaching-Classes.pdf

Laufer, B., & Shmueli, K. (1997). Memorizing new words: Does teaching have anything to do with it?. RELC Journal, 28(1), 89–108. https://doi.org/10.1177/003368829702800106

Lessard-Clouston, M. (2013). Word lists for vocabulary learning and teaching. The CATESOL Journal, 24(1), 287-304. http://www.catesoljournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2014/06/cj24_lessard_clouston.pdf

Lim, W. N. (2017, April). Improving student engagement in higher education through mobile-based interactive teaching model using Socrative [Paper presentation]. Global Engineering Education Conference (EDUCON) 2017, Athens, Greece. https://core.ac.uk/reader/148366880

Lu, C. (2004). The effects of reading articles and memorizing word lists on EFL high school students’ reading and vocabulary abilities[Masters thesis], National Taiwan Normal University.

Meara, P. (1995). The importance of early emphasis on L2 vocabulary. The Language Teacher, 19(2), 8-11.

Mehring, J. G. (2006). Developing vocabulary in second language acquisition: From theories to classroom (Working Paper No. 4). Hawaii Pacific University.

Méndez-Coca, D., & Slisko, J. (2013). Software Socrative and smartphones as tools for implementation of basic processes of active physics learning in classroom: An initial feasibility study with prospective teachers. European Journal of Physics Education, 4(2), 17-24. http://www.eu-journal.org/index.php/EJPE/article/view/86/83

Nurhasanah, F. (2020). The effectiveness of Socrative application for formative assessment in teaching vocabulary at SMA Muhammadiyah 1 Ponorogo [Undergraduate thesis]. IAIN Ponorogo.http://etheses.iainponorogo.ac.id/11252/1/SKRIPSI_210916060_FITRIANI%20NURHASANAH.pdf

Pennington, M. (2011, August 21). Why vocabulary word lists don’t work. Pennington Publishing Blog. https://blog.penningtonpublishing.com/reading/why-vocabulary-word-lists-dont-work

Pham, H. (2018). Integrating Quizlet and Socrative into teaching vocabulary. Issues in Language Instruction, 5(1), 27-28. https://doi.org/10.17161/ili.v5i1.7018

Qian, D. D. (1996). ESL vocabulary acquisition: Contextualization and decontextualization. The Canadian Modern Language Review, 53(1), 120–142. https://doi.org/10.3138/cmlr.53.1.120

Rofiah, N. L., & Waluyo, B. (2020). Using Socrative for vocabulary tests: Thai EFL learner acceptance and perceived risk of cheating. The Journal of Asia TEFL, 17(3), 966-982. http://dx.doi.org/10.18823/asiatefl.2020.17.3.14.966

Sanaoi, R. (1995). Adult learners' approaches to learning vocabulary in second languages. The Modern Language Journal, 79(1), 15-28. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1995.tb05410.x

Saraçoğlu, G., & Kocabatmaz, H. (2019). A study on Kahoot and Socrative in line with preservice teachers' views. Educational Policy Analysis and Strategic Research, 14(4), 31-46. https://doi.org/10.29329/epasr.2019.220.2

Shen, W. (2003). Current trends of vocabulary teaching and learning strategies for EFL Settings. Feng Chai Journal of Humanities and Social Science, 7, 187-224.

Subon, F. (2013). Vocabulary learning strategies employed by form 6 students. International Journal of Scientific and Research Publications, 3(6), 1-32. https://www.ijsrp.org/research-paper-0613.php?rp=P181368

Thornbury, S. (2002). How to Teach Vocabulary. Pearson.

Velayutham, V. A. P., Azman, M. A. B., Yunus, M. M., & Badusah, J. (2017). Sounds to words: Using Socrative to enhance English literacy. Creative innovation without boundaries: Selected papers from International Invention & Innovative Competition 2017 (pp. 188-192). MNNF. https://www.jflet.com/articles/using-socrative-student-response-system-to-learn-phrasal-verbs.pdf

Vurdien, R. (2021). Using Socrative student response system to learn phrasal verbs. Journal of Foreign Language Education and Technology, 6(1), 1-30. https://bit.ly/3jLVapY

Widyastuti, P. (2016). Using Socrative and smartphones as a tool to assess and evaluate students’ vocabulary knowledge Proceedings of the 3rd International Language and Language Teaching Conference, 2016 (pp. 39-45). Sanata Dharma University Press.

Wilcox, B., & Morrison, T.G. (2013). The four Es’ of effective vocabulary instruction. Journal of Reading Education, 38(2), 53-57.

Yamamoto, Y. (2014). Multidimensional vocabulary acquisition through deliberate vocabulary list learning. An International Journal of Educational Technology and Applied Linguistics 42(1), 232-243. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2013.12.005

Yarahmadzehi, N., & Goodarzi, M. (2020). Investigating the role of formative mobile based assessment in vocabulary learning of pre-Intermediate EFL learners in comparison with paper based assessment. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 21(1), 181-196. https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.690390