Introduction

The COVID-19 pandemic took a very short time to grasp the whole world with its cruelty forcing individuals and institutions to work from home in order to keep social distance. The government of Bangladesh followed the guidelines and closed all educational institutions on 16 March 2020. In the meantime, the University Grants Commission (UGC) urged all universities to start online education instead of traditional classes (UGC urges univs to continue classes online, 2020).

Online PBL (Project-Based Learning), Flip classroom, e-learning, distant learning, online classes, open online courses, and various online platforms were not new, but their application as an alternative to a physical classroom was not the type of study introduced by researchers (Sarker et al., 2019; Karim et al., 2019). The tertiary-level learners in Bangladesh were familiar with e-learning and learning through the support of technologies in a physical classroom. However, an online classroom, especially an English language learning classroom over a traditional classroom, was a new door in the learning sphere. Dudeney and Hockly (2007) proposed a guideline for three different dimensional courses on online language learning, which are

Course 1: A 100% online language learning course

Course 2: A blended language learning course

Course 3: A face-to-face course with additional online materials (p. 138-139).

This study examines the possibilities and challenges of the dimension of ‘Course 1’ but not as an independent language learning course. This study specifically focuses on those online ELL courses which generally stage in a traditional physical classroom as a part of an undergraduate program. It considers a complete version of a language classroom without direct contact between the teachers and learners but fulfills everything a traditional classroom offers. In a pandemic like COVID-19, where social distance was essential to restrict the spread of the disease and staying and working from home was a required guideline, an alternate classroom was a necessity that could replicate the traditional one without hampering the learning flow. This led the researcher to find the answer to the following two research questions,

- What are the possibilities of online English language learning classrooms to replace traditional classrooms during COVID-19?

- What challenges are associated with establishing such classrooms?

Literature Review

Are We Ready for the Next G? The Platform for Online Classroom as a Traditional Alternative

A significant difference between the previous century and this one is a radical shift in the form of communication. The development of human civilization has accelerated because of technology-based communication. “The rapid development of modern communication technologies has changed the areas of life including language teaching, language learning and language use” (Anh et al., 2019, p. 52). The change is evident as over 50% of the population access Internet-based forms of learning (The second half of humanity is joining the internet, 2019). These internet-based learning platforms are the byproducts of technology-based communication. It has been enhancing and augmenting communicative activities in a classroom through computer (Balcikanli, 2009). Online-based learning (e.g., MOOCs) has worldwide acceptance (Bonk et al., 2015). As a developing country, Bangladesh has a better chance of developing such learning as Zhang et al. (2020) found wider acceptance in developing countries where many people pursue their higher education through MOOC platforms. A MOOC platform has a higher possibility as Open Educational Resources (OERs) have various characteristics, including “openness, free access, and use and repurposing of the resources” (Motzo & Proudfoot, 2017, p. 86). These features can help to build ubiquitous learning networks to reduce the knowledge divide which separates societies (McGreal, 2013). Moreover, “the user acceptance of a specific e-learning platform is regarded as one of the essential factors to achieve institutional goals such as knowledge sharing, knowledge creation” (Amin et al., 2016, p. 11). Bangladeshi Universities followed a common objective of providing quality education and developed and used several online learning platforms, including Moodle, Google Classroom, VUES (Virtual University Expert System), and the like. (Amin et al.). These online versions of classrooms explore opportunities for reaching more teachers in different geographical locations (Guler, 2020).

Online Classroom: Possibilities and Opportunities

In order to establish an online classroom, the first thing needed is an internet-enabled operating device. A computer, laptop, or other smart devices would be acceptable for a successful online classroom. These devices are very common and handy to students. In their study, Bebell and Kay (2010) found students carrying and utilizing laptops or handheld tablets daily. Islam (2019) also found a similar situation in Bangladesh where “students like to use gadgets both in and outside the classroom” (p. 59). He also mentioned university students’ preference for mobile phones and other advanced media, especially smartphones, which can be more capable than laptops or computers. These internet-connected devices named this generation the “net generation” who grew up with the 21st Century technologies (Islam, 2019). The availability of smart devices and portable gadgets opens a new window for this generation of language learners. As of February 2020, Bangladesh had 166.114 million Mobile Phone subscribers in total (Mobile phone subscribers in Bangladesh, 2020), where there are 31.0 million smartphone users (Turner, 2020). Hossain (2018) claimed that the key portion among those smartphone users is that university students are very pertinent in applying technology in learning. The participants of Hossain (2018) claimed that the key portion among those smartphone users are the university students who are very pertinent in applying technology in learning. He also mentioned that Bangladeshi university learners have made the best use of smartphones to learn English.

Surely our language classrooms are becoming borderless with the expanded opportunities for the learners brought by technology (McDonough & Shaw, 2012). The internet is the most significant innovation that greatly impacts on the language learning platform. Internet-facilitated activity is the top-rated feather to current online technologies (McDonough & Shaw). Web-based platforms like Virtual Learning Environments (VLE) or Learner Management Systems (LMS) have the scope of storing course content that learners can access through the internet. The learners “can not only see course content, such as documents, audio, and video lectures, but also do activities such as quizzes, questionnaires, and tests, or use communication tools like discussion forums or text and audio chat” (Dudeney & Hockly, 2007, p. 137). Some VLEs, such as Blackboard and First Class, are not free, but Google Classroom, introduced by Google in 2014, has provided all the facilities without charging any fee.

Moreover, Google Docs, Drive, Calendar, and Forms can be integrated with it for more interactive learning and teaching (Islam, 2019). Google Classroom can be used on a laptop, desktop, or smartphone by installing its app version. These applications are compatible with portable gadgets and give users a new mode of experience during learning. Zilber (2013) referred to smartphone apps as a solid platform for English language learners in the modern days. Islam (2019) found Google Classroom as a medium that can be used to learn the four basic skills of English in a very innovative way. Al-Jarf’s (2019) student participants also found the online reading course was “a new way of improving their reading ability in English and a new way of doing homework” (p. 70). These technological inventive “open avenues for people to exchange knowledge, participate in online meetings, and undertake discussions in real-time, which were impossible hitherto for a learning environment.” These technological innovations motivated learners to share information and exchange knowledge in an online learning context (Shih, 2013).

One of the challenges of traditional classrooms is classroom management. A teacher needs much time to manage his/her class. The web 2.0 tools and classroom applications came to sort this out in the e-learning platform. A VLE or LMS can track learners’ presence and activities; accessing documents and forums can be monitored by the online instructor during course delivery (Dudeney & Hockly, 2007). Islam (2019) considered Google Classroom to have an exclusive design for teachers and students. Japar et al. (2019) identified many advantages for tutors regarding class management:

As for lecturers, Google Classroom can be used as a medium to share assignments and materials to be conveyed, besides this Google Classroom can also facilitate lecturers to monitor student discipline, because, with Google Classroom, lecturers can manage the time of collected each task, lecturers can find out where students are disciplined and lack discipline, of course with the consequence of reducing the value for those who are not disciplined. The discipline can be seen through the date of collection of tasks. (p. 508)

Iftakhar (2016) also considered Google Classroom as a medium for helping teachers to create and collect students’ assignments with the help of other Google services. She also explainedf that the teachers can also prepare their classes in advance. Even for evaluating the learners, these tools and applications are more convenient because of the automatically graded activities and tutor assessment (Dudeney & Hockly, 2007).

The wide range of e-learning tools not only covers web applications, blogs or video sharing sites but also grips the social networking sites namely Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, or LinkedIn (Lin, 2010). The popularity of these social networking sites can be used to make a classroom interactive. Many researchers worldwide have used Facebook for interaction, collaboration, and discussion. Moir (2010) acknowledged Facebook as an interactive tool and Mahmud and Ching (2012) also identified it as interactive and collaborative tool.

Karim et al. (2019) considered Facebook ‘live’ option as a tool for the frequent interaction between mentors and students. Facebook is such a dominating medium that it has been used as the connector to a wide range of language learners’ community (Kasuma & Wray, 2015). It surely can be a very effective and meaningful medium in an online EFL or ESL context (Kabilan et al., 2010). Klein et al. (2018) observed that the social networking application, WhatsApp helped to uphold the unity of an online class and minimized the space between students and teachers by establishing interaction. Simpson (2017) also found such social networking site beneficial for English language learners. The ESL or EFL educators can also integrate social networking sites to bring variation in learning modes (Lin et al., 2016).

With all such amenities and variations, an online classroom can be a convenient and flexible option for both learners and teachers. It is an attractive platform because of its flexibility (Lee, 2016) in time and place. Guler (2020) stated that “Online classes, unlike face-to-face ones, do not require teachers to be in one place at a certain time and utilize many learning tools, such as discussion boards (DBs), online assignment uploads, and blogs” (pp. 2-3). For students, online learning affords “greater flexibility and convenience than traditional learning” (Lee, 2017, p. 26). In addition, online classes can be uploaded on YouTube. The students “who miss the live class can be privileged by watching them later from YouTube. Coupled with this, learners who participate in the live class can also watch the classes later with a view to attain more mastery” (Karim et al., 2019, p. 255). Furthermore, they can easily be informed about assignments and collect the materials used in the classrooms and other information relating to their topics or courses (Japar et al., 2019). Even while submitting assignments and write-ups, an online classroom is hassle-free as it saves time, money, and paper(Islam, 2019). Finally, teachers and learners can access and continue these online classes whenever and wherever they want through their portable or smart devices (Muhaemin, 2019).

The internet is an open world for resources that can be used in language learning. Popular and established ELT methodologies emphasize interaction and engagement among the learners through meaningful and authentic texts and tasks. The use of web-based media “allows the use of more varied content, ranging from electronic books (e-books), learning videos, and podcasts, to the use of interactive multimedia” (Muhaemin, 2019, p. 69). Internet-based applications help learners access pronunciation to practice language skills which can be browsed from any computer to portable gadgets. The teacher can initiate Project-based tasks and activities, which are promising pedagogy as “students are expected to contribute to the shared outcome” through collaboration (Sampurna et al., 2018, p. 74).

Success in online learning: Bangladesh and beyond

The success of online classrooms is not abstract. The enormous studies on e-learning and online platform-based learning, the development of technologies, the popularity of social sites, and most importantly, the increasing demand for distance learning with minimum effort make the online classroom a successful mode of pedagogy. In their study, Karim et al. (2019) exhibit the success of “10 Minute School”, a Facebook platform-based online classroom that produced over 4,000 videos to educate more than 150,000 students free of cost. The founder Ayman Sadiq designed that classroom emphasizing the practical usage of English along with spoken English, business English, presentation and communication skills, interview skills, and CV writing skills in such a format that anyone can learn anything, at any time, from anywhere (Karim et al., 2019). It is fascinating to learn about Islam’s (2019) study; he claimed that Daffodil International University “is the first in Bangladesh to make the use of Google Classroom compulsory for teaching and learning in each and every department” (p. 58). Latifa et al. (2019) concluded their study with a successful story as they developed the English-speaking skill of their participants, who are from Daffodil International University.

The number of studies worldwide in the last decade confirms the success of online English language learning. The researchers also made it pictorial by proving them successful in English language learning. For example, in 2018 alone, MOOCs were reached to over 100 million learners registered in 11,400 MOOCs (Shah, 2019). Al-Shammari (2020) found that the students of Kuwait International Law School were positive about using social media to acquire English properly. He also disclosed their heavy dependence on social media during the COVID-19 pandemic to complete their academic year 2019-2020. Al-Jarf’s (2019) study on first-year Arabian EFL students proved online instruction “a powerful tool for improving students’ reading skills in English” (p. 71). Lee’s (2017) study on the ‘effectiveness of blogging’ settled that “blogging not only empowers students to be creative with the content, but also promotes attention to language forms” (p. 19). Sampurna et al. (2018) mentioned Chang’s (2017) study, where six Applied English students in Taiwan completed a project through Facebook by producing a contract, a thesis, and a presentation.

Online classroom is not a fairy tale: The challenges

All the success manifesto does not make an online classroom a fairy tale. The researchers find it challenging to involve their participants in this learning mode. They consider students’ motivation a prime concern for active participation in online platform-based learning. The learners need to be positive, enthusiastic, and motivated from the early stage of the course to maximize their benefit (Anh et al., 2019). Different researchers feel the adequacy of self-discipline and self-motivation to be involved in the learning process (Lee, 2016). Lee (2017) identified a degree of autonomy as prerequisite for students learning in online platforms. They need to be prompted through positive outcomes or consequences to learn. Sampurna et al. (2018), in their study, identified the lack of consequence behind the affected participation in chat tools. Al-Jarf (2019) also identified the absence of course grades hindering Saudi college students’ participation in online learning. However, only response or showcasing presence might not be enough. The learners need to be active to enhance participation. For example, the participants from Al Jarf’s study only “wrote thank you notes and compliments rather than real responses” (p. 71).

At the same time, teachers or instructors must also be active. Teachers must be present and “need to fine-tune their participation level depending on the teaching context, learners’ responses, and preferences” (Sampurna et al., 2018, p. 86). The dimension of teachers’ roles also changed to adapt to such classrooms. Their increased role “consists of three elements: instructional design and organization (e.g., setting curriculum, deadlines); facilitation of discourse (e.g., prompting discussions, encouraging, acknowledging, or reinforcing student contribution); and direct instructional activities (e.g., giving feedback, assessing student understanding)” (p. 76). When a teacher is competent enough to initiate these roles in his/her classroom, it is possible to replace a traditional class. Dixson (2010) drew three concluding lines refereeing to effective online instruction. They are “1) online instruction can be as effective as traditional instruction; 2) to do so, online courses need cooperative/collaborative (active) learning and 3) strong instructor presence” (p. 1).

Online language teaching and learning are very different from the traditional way. In order to initiate an online course, two major issues should be considered: 1) proper technological knowledge of both operating devices/gadgets and online tools or applications; 2) proper training to operate those devices/gadgets and online tools or applications (Al-Jarf, 2019; Anh et al., 2019; Compton, 2009; Islam, 2019; Muhaemin, 2019). Hockly and Dudeney (2018) explained that teachers who need proper training on applying technologies in teaching and learning might face many challenges. They also advise online tutors to take an online course as a learner before starting teaching (Dudeney & Hockly, 2007). Compton (2009) referred to skills that online language teachers should acquire. He divided online language teaching skills into three categories: “a) technology in online language teaching; b) pedagogy of online language teaching; and c) evaluation of online language teaching” (p. 92). He wanted online language teachers to educate themselves on technology, methodology, and evaluation.

The wide acceptance of online tools has been generated from social networking sites with various possibilities to connect and collaborate with learners. However, the question whether they are enough to replace a traditional classroom persists. Researchers studying different tools and applications have found different challenges in their studies. For instance, Sampurna et al. (2018) found chat tools such as WhatsApp and LINE practical but inadequate in encouraging learners’ participation. Islam (2019) found that providing slides in Google Classroom is not enough to compete with the conventional classroom in learning English. He felt the presence of face-to-face interaction through live lecturing, video chatting, and messaging was helpful teachers to identify the “problem of the students by eye contact which is not possible by Google Classroom” (p. 63).

However, the choices of online tools, applications, and operating devices also need to be specific. If the stakeholders find them unfamiliar, it will be challenging for all the parties to make the online classroom successful. Dudeney and Hockly (2007), Holzweiss et al. (2014), and Sampurna et al. (2018) identified the familiarity of online tools, software, and devices available, with the effectiveness of online learning, gaining confidence and affection at the participation level. Anh et al. (2019) referred that “unfamiliarity with blended learning can initially hold learners back” (p. 57). Islam (2019) found it challenging as some of his student participants did not know the basic functions of Google Classroom. The addition of the unfamiliar online tools can lead to low or no participation in online learning. Amin et al. (2016) called those technologies a waste of resources that the users did not widely appreciate. Holzweiss et al. (2014) believed that students with more experience in online courses benefit more than students who are new to distance education.

The traditional English language classroom has the environment to learn from peers. Peer correction or peer teaching can guide students work cooperatively (Ur, 1999). So, it is necessary to maintain engagement among peers. She also mentions group work and collaboration, where the students in a classroom must work together to have an interactive class (Ur, 1999). However, it is considered a challenge in an online classroom since the lack of peer interaction can discourage students’ participation (Park, 2015; Sampurna et al., 2018). Even for discussing educational material, learners are more comfortable discussing it with friends than with their teachers (Sarker et al., 2019). The learners refer to the tools or applications without this feature as inconvenient. The participants in Islam’s (2019) study consideredGoogle Classroom time-consuming, and a hindrance to privacy as learners cannot communicate with each other privately.

Interestingly, even the learners’ positive attitudes towards participation and all the technological support may go in vain without a proper and stable internet connection. It is somehow possible to have distance learning through the support of different software and soft materials. However, having an online classroom without an internet connection is impossible. The internet is the nucleus of the online platform-based classroom. Anh et al. (2019) categorized internet connection as one of the disadvantages of an online English program. Al-Jarf (2019) considered the lack of internet connectivity responsible for hands-on practice. Islam’s (2019) participants from Bangladesh wanted offline services from online tools and applications as they found the internet costly. Until December 2019, the total number of recorded subscribers in Bangladesh was 99.428 million; interestingly, 93.681 million were mobile internet users (Number of internet subscribers reaches over 99 million, 2020). The population of Bangladesh also faced low-speed connections. Unfortunately, amid the coronavirus pandemic, the download speed in the country was the lowest among the 42 markets covered by a study conducted by Open signal, a Hong Kong-based international mobile analytics organization specializing in quantifying mobile network experience (Islam, 2020). According to that study, in Bangladesh, mobile internet download speed downgraded from 9.3 Mbps in the first week of February to 7.8 Mbps in the last week of March 2020. The students of Google Classroom in Islam’s (2019) study referred to the internet connection and speed as “terrible.” Moreover, this could be a severe issue as the university learners from different and remote places in Bangladesh went back to their hometowns amid the shutdown of educational institutions because of the COVID-19 pandemic. These learners can fall into a serious problem not only by joining online classes but also by participating in different tasks and activities and submitting assignments and write-ups.

Besides the internet connection and low data transfer speed, learners’ reluctance and lack of a positive attitude towards accommodating online culture can cause problems when establishing an online classroom. Xu et al. (2005) identified online learners passive towards their involvement in learning activities. Al-Jarf’s (2019) students were reluctant to use the internet because of cultural approbation, and some of her students were very dependent on the traditional book and instruction. In addition, Lai’s (2016) participants’ readiness impacted on group dynamics.

It can be a generalization that an online classroom helps online tutors save valuable time as the class can be conducted from anywhere. Interestingly, it is not the same in reality. Dudeney and Hockly (2007) considered online tutoring more time-consuming than face-to-face teaching. The tutors need more time “at the design, development stage and also during the tutoring stage” (p. 142). Moreover, replying to individual students and maintaining a relationship with the learners need additional time. Sometimes the learners have “unrealistic expectations of their tutors in terms of response time and availability” (p. 142).

Research Methodology

The core objective of this study is to evaluate the place of online English language learning as an alternative to traditional class at the tertiary level. Unfortunately, the Coronavirus epidemic left us no choice but to work from home and learn from home. Most of the universities in Bangladesh introduced basic and advanced English language learning courses in almost all disciplines, including English. To capture the core picture, teachers’ perception was also recorded. A quantitative research method was employed through descriptive design to investigate the possibilities and challenges of online classrooms (Watt, 2015).

Participants

Both teachers and students from different universities in Bangladesh participated in the study. The faculty members were selected based on convenience sampling, and the student participants were selected through snowball sampling (Creswell, 2012). However, the participants needed to fulfill two basic requirements: Experience learning/teaching online classes after the spread of the pandemic, COVID-19 and learning/teaching the English language in those classes. The researcher also addressed all the ethical concerns from both the students and the teachers under the research ethics guideline and data were collected after they provided their consent. A total of 114 participants from 12 universities across the country participated in the study. Among them, 29 were teachers, and 85 were students. Out of those 29 teachers, 18 were male, and 11 were female. All of them were part of the English department, and they held positions from Lecturer to Associate Professor with from 0 to 15 years or more of experience. Of the 85 student participants, 46 were male, and 39 were female. They were studying in different semesters of different disciplines across the universities, but all of them had taken English language learning online courses after the spread of the COVID-19 pandemic. It is also necessary to mention that only one was part of the Graduate program while the rest belonged to the Undergraduate program.

Instrument

Separate questionnaires were designed for the teacher and student participants to identify the possibilities and challenges of the online classroom as an alternative to the traditional classroom. All research questions were carefully designed based on the work of different researchers. Scaled questions were introduced to elicit opinions and synchronize the study’s objectives. Those questions followed a Likert scale of 5 choices ranging from strongly agree to strongly disagree with the options of neither agree nor disagree (McDonough & McDonough, 2014). A total of 16 questionnaires were designed for each category of participants (Appendix 1 and Appendix 2). Every questionnaire consists of four sections; the first section collected the participants’ profiles and experiences in the online classroom. The second section surveyed the possibilities of an online classroom (eight questions for the teachers and nine for the students). The third section surveyed the challenges of the online classroom (nine questions for the teachers and eight for the students). The final section gave the option to add additional comments for the participants and asked their opinions about the online classroom. It is necessary to mention that the students’ questionnaire was translated into the local language for better comprehension.

Data collection

A cross-sectional method was used to gather data from the participants (Watt, 2015). First, considering the shutdown caused by COVID-19, an electronic survey was created with Google Forms. Later the questionnaires were shared with the participants through email, Facebook Messenger, WhatsApp, and different teachers’ groups on Facebook.

Data analysis

The automatic data collection option from Google Forms was used producing a Google Spreadsheet that facilitated the data analysis. For a deeper analysis of the data, SPSS version 25 was used. In order to explore the possibilities and challenges of online English language learning classes instead of traditional physical classes, the data were analyzed based on the format of the questionnaires. The first section depicts the scope of online English language learning classes and the second section represents the challenges while establishing those classes. Figures representing the data have been designed into pie charts (Appendix 3 & Appendix 4). It is necessary to mention that the responses regarding ‘strongly agree’ and ‘agree’ are combined under the ‘agree’ category to portray a concrete outcome referred by the respondents.

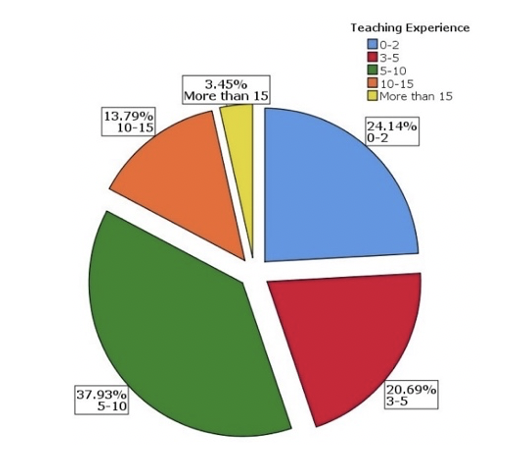

Figure1: Teaching experience

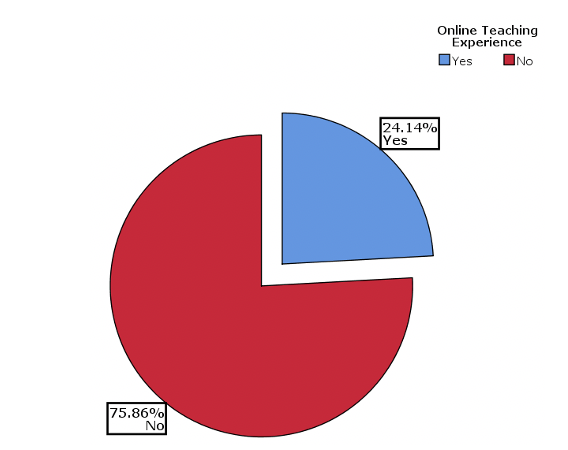

Figure 2: Experiences in teaching online English courses/classes before Covid-19.

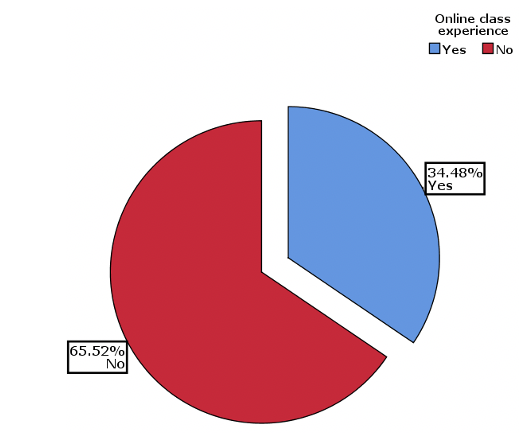

Figure 3: Experiences in participating in online courses/classes before Covid-19

Among the teachers (Figures 1, 2, and 3), a significant number (38%) had teaching experience of 5-10 years. However, it is interesting that only 24% had experience teaching online. Furthermore, another interesting finding was that more than 65% of the teachers needed to gain experience before in any online class or course

Students’ profile

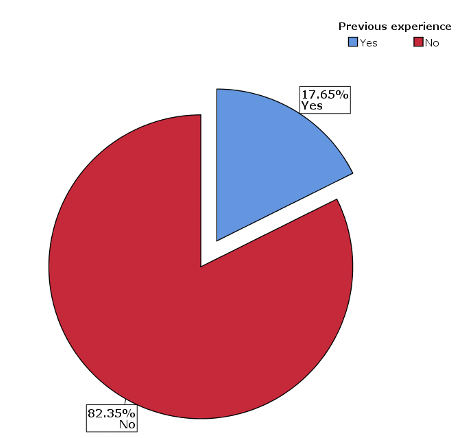

Figure 4: Experiences in participating in online courses/classes before Covid-19

Though most the students are from the English department, a significant portion is from other disciplines. Nevertheless, at the time of the study, all students were participating or had participated in at least one English language learning course after the spread of COVID-19. However, only 17% (Figure 4) participated in online English language classrooms before the COVID-19 era.

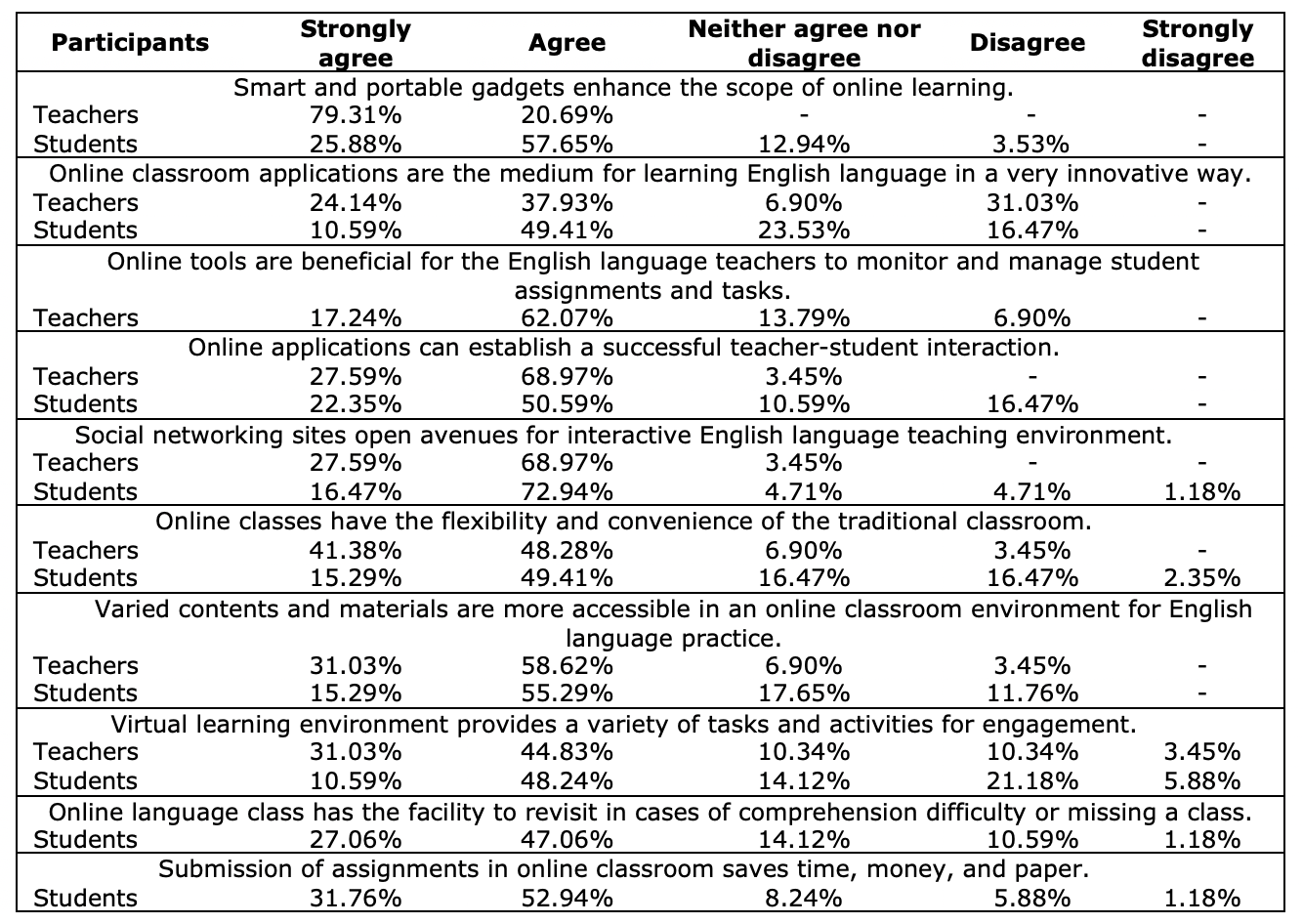

Possibilities of online classroom

Data analysis is presented following the participants’ responses to the possibilities of online English language classes. Several prompts were focused on measuring the scope of online English language classrooms as an alternative to traditional classrooms. Table 1 summarizes the record of the teachers’ and students’ responses and represents the data analysis. Pie charts are also illustrated in Appendix 3 for a more analytical visual representation.

Table 1: Possibilities of online English language classroom as an alternative

Online classrooms for learning the English language have been possible because of technological advancement which makes smart and portable gadgets available to the masses. All teachers and over 83% of students believe that smart and portable gadgets can enhance the scope of online platform-based learning. In response to the prompt, ‘Online classroom as a way to learn the English language innovatively,’ over 60% of teachers and students agreed. However, a significant portion of the teachers, above 30%, disagreed. Monitoring students’ performance and assessing assignments and class works is an arduous journey for teachers. However, almost 80% of online English language teachers found online tools beneficial in this journey. Table 1 discloses an exciting discovery regarding online applications’ ability and functions. Over 90% of teachers and more than 70% of students acknowledge that online applications can establish successful teacher-student interaction through live classroom facilities, lecturing, video chatting, and messaging with multiple students. However, the rapid growth of social networking sites, namely Facebook, Instagram, Twitter, LinkedIn, blogs, video sharing sites, and web applications, also develop an interactive English language teaching environment.

The ratio between the statements of “agree” and “disagree” is quite dramatic. Only 5.89% of students do not think that social networking sites can open avenues for interactive English language classes, compared to 96.56% of teachers and 89.41% of students who think that they could be useful. Unlike traditional classrooms, students and teachers can participate in an online classroom from almost any place and browse the contents for English language learning at any time of the day. Almost 90% of teachers and 65% of students found online English language classes more flexible and convenient than traditional EL classes. Less than 20% of students and 5% of teachers did not share that opinion. At the same time, the online classroom environment seemed to enhance English language practice opportunities for the learners as various contents and materials were more accessible there. Table 1 shows that 89.65% of teachers and more than 70% of students found the internet more accessible for additional English language practice than the physical language class. Though the teachers use different tasks and activities in their traditional classroom to engage their learners, the virtual world has more varieties than the traditional one. In response to the prompt, over 70% of the teachers and almost 60% of the students agreed, whereas less than 15% of teachers and just above 25% of students disagreed with this viewpoint. Only the students were prompted with the viewpoint, “Online language class has the facility to revisit in cases of comprehension difficulty or absences.” Over 70% of students responded positively. They also seemed in favor of online classes when it came to the submission of assignments or any written assignments. Responses in Table 1 suggested that online platform-based classrooms had created an opportunity for the 84.7% of students to submit their assignments within a shorter period of time and spending less money and paper when compared to the regular classroom.

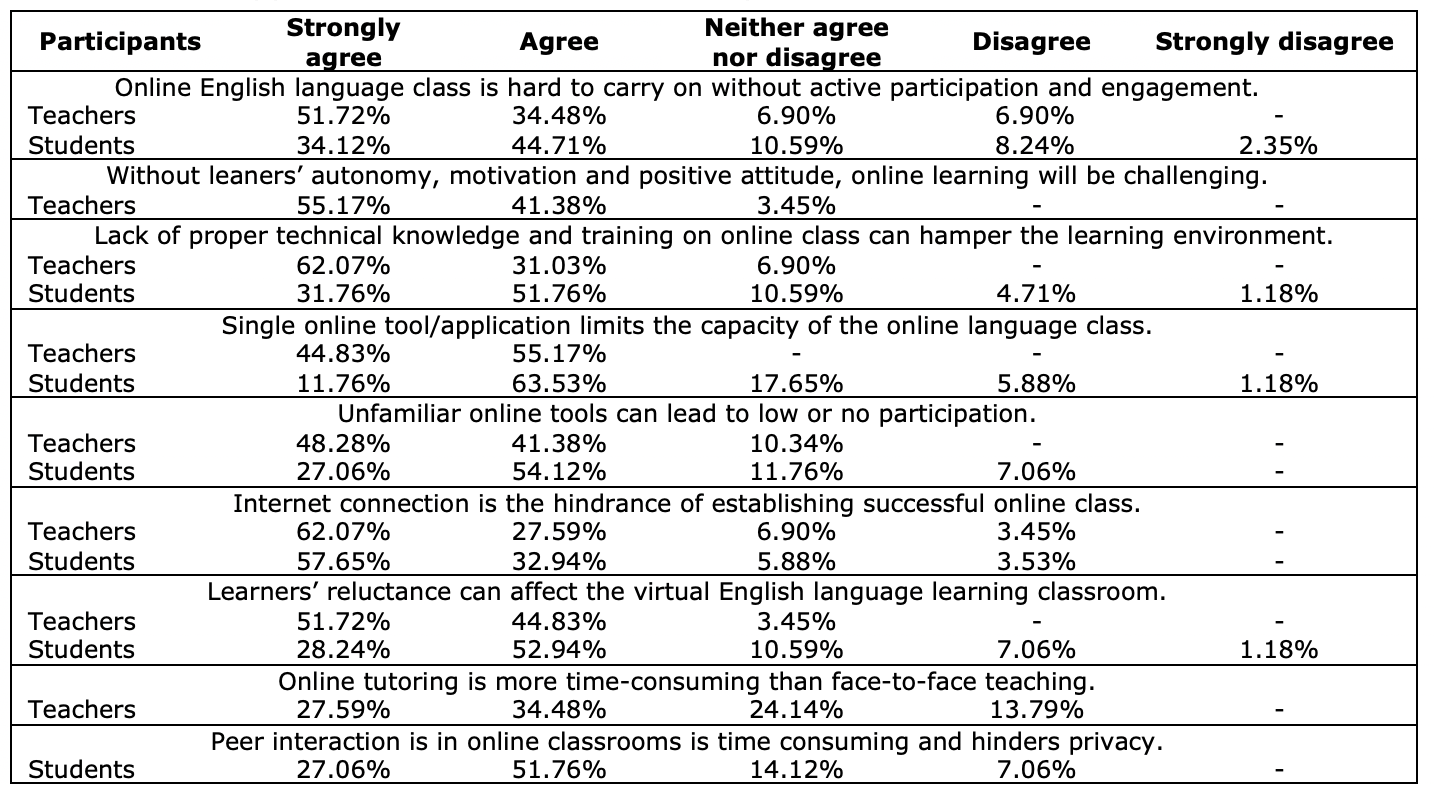

Challenges of the online classroom

Teachers’ and students’ opinions reflected the challenges of an online class. Table 2 summarizes the opinions depicting the challenges from both the teachers’ and learners’ points of view and supporting the data analysis. In addition, Appendix 4 illustrates the data in pie charts.

Table 2: Challenges of online language class as an alternative

Developing an online English language class is hard if the teachers and learners do not participate actively. Over 85% of teachers and 77% of students agreed with the statement, while less than 7% of teachers and just above 10% of students did not agree. At the same time, 96.55% of teachers agreed that the online language class would be challenging if the learners were not motivated, autonomous, and positively driven toward collaboration. No teacher opposed that idea. Modern technologies might not help in an online English language learning class if the participants do not know how to operate them. Teachers also agreed with the prompt that the lack of proper technical knowledge and training from experts about the application and function of online classrooms could hamper the learning environment. Table 2illustrates that over 94% of teachers and 83% of students considered it a challenge in the online English language classroom. Online tools function best when they work collaboratively. So using only one tool/application to make an online classroom successful is challenging. All the teachers and over 75% of the students agreed to consider it a challenge when learning English online.

Tools/applications also need to be familiar because unfamiliar online tools can lead to low or no participation in online language learning. Almost 90% of teachers and over 80% of students reported ‘unfamiliar online tools’ as a challenge for the online learning environment, only 7.06% of students disagreed, and none of the teachers disagreed. Table 2explicitly displays how far unavailability and slowness of the internet connection in remote areas and the high cost of the internet can be challenging for the stakeholders. Around 90% of the participants from both student and teacher categories considered internet connection to be a challenge. In response to the prompt where the learners’ reluctance was categorized as a challenge for the teachers in online platform-based teaching, more than 80% of learners accepted it as a challenge along with more than 95% of teachers. Many teachers found online English language learning classes more time-consuming than face-to-face classes. It can be seen that one-third of the total teachers have a similar viewpoint, while around 15% disagreed with it. Online classrooms do not give many options to communicate with peers; instead, they took time and limited privacy. Almost 80% of the students agreed and considered it a challenge for online platform-based learning.

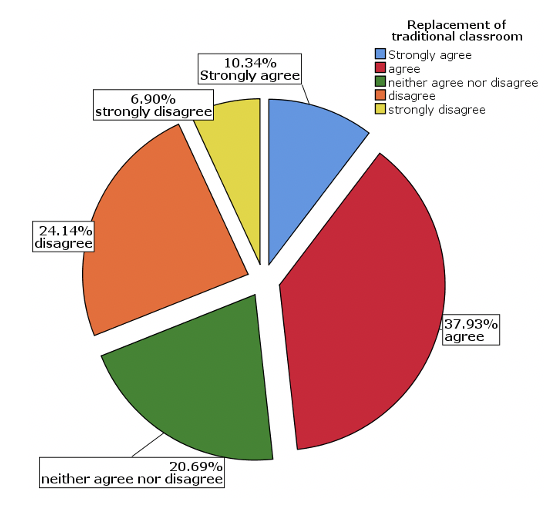

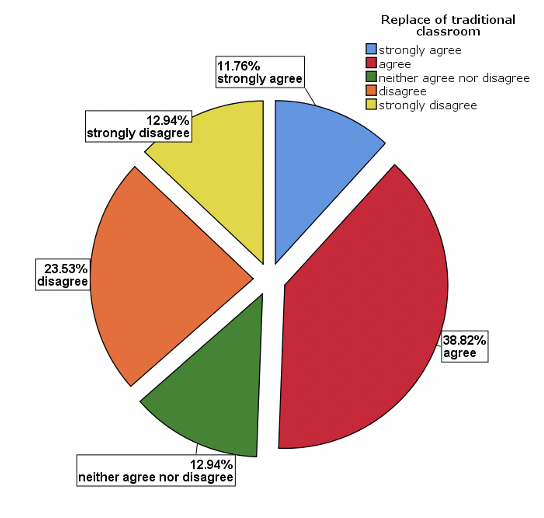

Attitude towards online classroom as an alternative

At the end of the questionnaires, a prompt was presented to identify the participants’ attitudes regarding the place of online English language classrooms as an alternative to traditional classrooms. Over 48% of teachers and more than 50% of students stated that online classrooms could replace the traditional classroom (Figures 5 & 6). However, 31% of teachers and 36% of students did not think that online English language classrooms could replace traditional classrooms in the near future.

Figure 5: Online classrooms can replace traditional classrooms in the future (Teachers)

Figure 6: Online classrooms can replace traditional classrooms in the future (Students)

Results

The data reflect the answers to the research questions. Based on the responses from the participants, the following possibilities and challenges of online English language classrooms can be acknowledged from both the teacher’s and learner’s perspectives.

Possibilities of online classrooms

The study by Martín-Monje and Barcena (2014) found that of 26 of the language learning MOOCs (Massive Open Online Courses) offered through universities, English and Spanish were the most popular languages. This statistic favors the prospect of online English language learning. Moreover, the data analyzed in the present study suggests that students and teachers have positive attitudes toward online teaching/learning, and the recently developed technologies can make online classes more interactive. The study shows that the availability of portable smart gadgets, the flexibility and convenience in terms of time and place of online classes, simple class management of both teachers’ and learners’ accounts, the unlimited access to varied contents, materials, and tasks, and most interestingly, the facility to revisit the course content were the most positive in favor of online English classes. Hockly’s (2015) evaluation based on almost similar factors, such as cost, convenience, learner expectations, developments in technology, and changing paradigms within education, made her refer to the fact that “online learning is here to stay” (p. 2).

Challenges of online classrooms

The data confirms that teachers and learners consider online classrooms a challenge when there is no active participation or engagement. Many researchers in their studies find it challenging to involve and engage the learners in an online platform-based ELL class (Al-Jarf, 2019; Lee, 2017; Sampurna et al., 2018). The present study also shows that teachers find it challenging to conduct an online language classroom if the learners’ autonomy, motivation, and positive attitudes are missing. Besides, it is a default requirement for teachers and learners to have proper training and knowledge of gadgets and applications related to English language learning. Hockly (2015) recommended effective teacher training for providing competent online courses, and appropriate tools and applications for learners’ engagement, adaptability, familiarity, and proper internet connections.

Recommendations

Based on the results, the following recommendations can be recommended:

Zhu and Bonk (2020) referred to three types of technologies for a successful online classroom, “(1) synchronous communication technologies (Google Hangouts and YouTube Live), (2) asynchronous communication technologies (discussion forums, blogs, Padlet, Slackbot, and various social media), and (3) feedback tools (learning analytic tools)” (pp. 41-42). The adoption of these technologies can help the teachers and learners to overcome the challenges they often face. Dixson (2010) also suggested that “multiple opportunities for communication may be more important than any particular channel” (p. 7).

The learners need to be motivated in order to be engaged in the classroom. Al-Jarf (2019) stated that instructors must prompt and motivate their learners to encourage students to participate in the online classroom. Furthermore, based on Dudeney and Hockly’s (2007) advice, teachers need to enroll in an online course even before starting teaching online. Overall, to take over a face-to-face classroom, the online classroom must pass the ‘TEA’ test (Training, Equipment, and Access) (Harmer, 2001), which will only be possible if there is proper training for teachers and learners on the new techniques and strategies along with the procedures, appropriateness of all technological equipment, and access to all sources through for immediate learning.

Conclusions

The present review has shown an optimistic future for the online language classroom as an alternative to the traditional classroom. Although there are still some challenges to resolve, with proper training and new technologies there is hope for the future. While there are still challenges of active participation, learners’ autonomy, unfamiliar online tools, internet speed and so on, there are many positive aspects as well, including the availability of smart and portable gadgets, innovation of teaching and learning strategies through online tools, advanced technology for student management, accessibility and communication through social network, varied contents and tasks and of course the flexibility in terms of time and place. At the same time, the positive attitude of the teachers and students towards online learning establishes a strong prospect of online English language learning class as an alternative to the traditional one in the coming future.

References

Al-Jarf, R. S. (2019). Teaching reading to EFL freshman Arabic students online. Arabistics of Eurasia, (8), 57-75. http://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED613084.pdf

Al-Shammari, A. H. (2020). Social media and English language learning during Covid-19: KILAW students' use, attitude, and prospective. Linguistics Journal, 14(1), 259-275.

Amin, M. K., Akter, A., & Azhar, A. (2016). Factors affecting private university students’ intention to adopt e-learning system in Bangladesh. Daffodil International University Journal of Business and Economics, 10(2), 10–25. http://hdl.handle.net/20.500.11948/1549

Anh, V. T. L., Hung, N. P., & Thao, N. T. P. (2019). Design and implementation of empower English program online (EEPO) for students and learners of Ho Chi Minh City University of Transport. European Journal of Engineering Research and Science, 4(9), 52–57. https://doi.org/10.24018/ejeng.2019.4.9.1513

Balcikanli, C. (2009). Long live, YouTube: L2 stories about YouTube in language learning. In A. Shafaei & M. Nejati (Eds.), Annals of Language and Learning: Proceedings of the 2009 International Online Language Conference (IOLC 2009) (pp. 91–96). Universal.

Bebell, D., & Kay, R. (2010). One to one computing: A summary of the quantitative results from the Berkshire Wireless Learning Initiative. The Journal of Technology, Learning and Assessment, 9(2). https://ejournals.bc.edu/index.php/jtla/article/view/1607

Bonk, C., Lee, M., Reeves, T., Reynolds, T. (Eds.). (2015). MOOCs and open education around the world. Routledge.

Compton, L. K. L. (2009). Preparing language teachers to teach language online: A look at skills, roles, and responsibilities. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 22(1), 73-99. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588220802613831

Creswell, J. W. (2012). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluation qualitative and quantitative research (4th ed.). Pearson.

Dixson, M. D. (2010). Creating effective student engagement in online courses: What do students find engaging? Journal of the Scholarship of Teaching and Learning, 10(2), 1–13. https://scholarworks.iu.edu/journals/index.php/josotl/article/view/1744

Dudeney, G., & Hockly, N. (2007). How to teach English with technology. Pearson.

Guler, N. (2020). Preparing to teach English language learners: Effect of online courses in changing mainstream teachers’ perceptions of English language learners. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 14(1), 83-96. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2018.1494736

Harmer, J. (2001). The practice of English language teaching (3rd ed.). Pearson.

Hockly, N. (2015). Developments in online language learning. ELT Journal, 69(3), 308–313. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccv020

Hockly, N., & Dudeney, G. (2018). Current and future digital trends in ELT. RELC Journal, 49(2), 164–178. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688218777318

Holzweiss, P. C., Joyner, S. A., Fuller, M. B., Henderson, S. A., & Young, R. (2014). Online graduate students’ perceptions of best learning experiences. Distance Education, 35(3), 311–323. https://doi.org/10.1080/01587919.2015.955262

Hossain, M. (2018). Exploiting smartphones and apps for language learning: A case study with the EFL learners in a Bangladeshi university. Review of Public Administration and Management, 6(1). https://doi.org/10.4172/2315-7844.1000241

Iftakhar, S. (2016). Google classroom: What works and how. Journal of Education and Social Sciences, 3(1), 12-18. https://jesoc.com/wp-content/uploads/2016/03/KC3_35.pdf

Islam, M. S. (2019). Bangladeshi university students’ perception about using Google classroom for teaching English. Psycho-Educational Research Reviews, 8(2), 57-65. https://perrjournal.com/index.php/perrjournal/article/view/160

Islam, M. Z. (2020, April 14). Mobile internet slowest in Bangladesh among 42 countries. The Daily Star. https://www.thedailystar.net/business/news/mobile-internet-slowest-Bangladesh-among-42-countries-1892761

Japar, M., Fadhillah, D. N., & Syarifa, S. (2019). Civic education through E-Learning in higher education. Proceedings of the 1st International Conference on Education Social Sciences and Humanities (ICESSHum 2019). https://doi.org/10.2991/icesshum-19.2019.81

Karim, A., Shahed, F. H., Rahman, M. M., & Mohamed, A. R. (2019). Revisiting innovations in ELT through online classes: An evaluation of the approaches of 10 minute school. The Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education 20(1). https://doi.org/10.17718/tojde.522729

Kabilan, M. K., Ahmad, N., & Abidin, M. J. Z. (2010). Facebook: An online environment for learning of English in institutions of higher education? Internet and Higher Education, 13(4), 179–187. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.iheduc.2010.07.003

Kasuma, S. A. A., & Wray, D. (2015). An informal Facebook group for English language interaction: A study of Malaysian university students’ perspectives, experiences and behaviours. 5th Annual International Conference on Education & Amp; e-Learning (EeL 2015).

Klein, A. Z., Da Silva Freitas, J. C. Junior, Da Silva, J. V. V. M., Barbosa, J. L.V., & Baldasso, L. (2018). The educational affordances of Mobile Instant Messaging (MIM): Results of Whatsapp® used in higher education. International Journal of Distance Education Technologies, 16(2), 51–64. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijdet.2018040104

Lai, A. (2016). Mobile immersion: An experiment using mobile instant messenger to support second-language learning. Interactive Learning Environments, 24(2), 277–290. https://doi.org/10.1080/10494820.2015.1113706

Latifa, A., Nur, R., & Amaluddin. (2019). Utilizing Google classroom application to teach speaking to Indonesian EFL learner. The Asian EFL Journal, 24(4.1), 176–192.

Lin, V., Kang, Y-C., Liu, G-Z., & Lin, W. (2016). Participants’ experiences and interactions on Facebook group in an EFL course in Taiwan. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 25, 99-109. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-015-0239-0

Lee, L. (2016). Autonomous learning through task-based instruction in fully online language courses. Language Learning & Technology, 20(2), 81-97. https://scholarspace.manoa.hawaii.edu/bitstream/10125/44462/1/20_02_lee.pdf

Lee, L. (2017). Learners' perceptions of the effectiveness of blogging for L2 writing in fully online language courses. International Journal of Computer-Assisted Language Learning and Teaching (IJCALLT), 7(1), 19-33. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijcallt.2017010102

Lin, T. (2010). The use of Facebook for online discussions among distance learners. Turkish Online Journal of Distance Education, 11(4), 72-81. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1042437

Mahmud, M. M., & Ching, W. S. (2012). Facebook does it really work for L2 learners. Academic Research International, 3(2), 357-370.

Martín-Monje, E., & Bárcena, E. (Eds.). (2014). Language MOOCs: Providing learning, transcending boundaries. De Gruyter. https://doi.org/10.2478/9783110420067

McDonough, S., & McDonough, S. (2014). Research methods for English language teachers. Taylor & Francis.

McDonough, J., Shaw, C., & Masuhara, H. (2013). Materials and methods in ELT: A teacher’s guide (3rd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

McGreal, R. (2013). Introduction: The need for open educational resources. In R. McGreal, W. Kinuthia, & S. Marshall (Eds.) Open educational resources: Innovation, research and practice. Commonwealth of Learning. https://oasis.col.org/colserver/api/core/bitstreams/f9841d8c-3253-4278-a2ae-fdc2fba0f273/content

Mobile Phone Subscribers in Bangladesh February, 2020. (2020, March 1). Bangladesh Telecommunication Regulatory Commission. Retrieved April 18, 2020, from http://www.btrc.gov.bd/content/mobile-phone-subscribers-Bangladesh-february-2020

Moir, S. (2010, March 12). Social media marketing business advantages of Facebook vs. Twitter Part 4. Release-News. https://mail.release-news.com/news/37-business/2864-social-media-marketing-business-advantages-of-facebook-vs-twitter-part-4

Motzo, A., & Proudfoot, A. (2017). MOOCs for language learning – opportunities and challenges: The case of the Open University Italian beginners’ MOOCs. In Q. Kan & S. Bax (Eds.), Beyond the language classroom: Researching MOOCs and other innovations (pp. 85-97). Research-publishing.net.

Muhaemin. (2019). Massive Open Online Course: Opportunities and challenges in state Islamic higher education in Indonesia. The Asian EFL Journal, 24(4.1), 61–71.

Naleen, V. C. (2019). Effectiveness of mobile learning to improve letter writing skills through scaffolding using WhatsApp – A study on working adults. Pan-Commonwealth Forum 9 (PCF9). http://hdl.handle.net/11599/3239

Number of internet subscribers reaches over 99 million. (2020, February 11). The Financial Express. https://thefinancialexpress.com.bd/national/number-of-internet-subscribers-reaches-over-99-million-1581322572

Park, J. Y. (2014). Student interactivity and teacher participation: An application of legitimate peripheral participation in higher education online learning environments. Technology, Pedagogy and Education, 24(3), 389–406. https://doi.org/10.1080/1475939x.2014.935743

Sampurna, J., Kukulska-Hulme, A., & Stickler, U. (2018). Exploring learners’ and teacher’s participation in online non-formal Project-Based language learning. International Journal of Computer-Assisted Language Learning and Teaching, 8(3), 73–90. https://doi.org/10.4018/ijcallt.2018070104

Sarker, M. F. H., Al Mahmud, R., Islam, M. S., & Islam, M. K. (2019). Use of e-learning at higher educational institutions in Bangladesh. Journal of Applied Research in Higher Education, 11(2), 210–223. https://doi.org/10.1108/jarhe-06-2018-0099

Shah, D. (2019, May 29). Year of MOOC-based degrees: A review of MOOC stats and trends in 2018. EdSurge.https://www.edsurge.com/news/2019-01-02-year-of-mooc-based-degrees-a-review-of-mooc-stats-and-trends-in-2018

Shih, R.-C. (2013). Effect of using Facebook to assist English for business communication course instruction. Turkish Online Journal of Educational Technology, 12(1), 52–59. http://www.tojet.net/articles/v12i1/1216.pdf

Simpson, J. (2017). Using Facebook in an EFL Business English writing class in a Thai university: Did it improve students’ writing skills?Proceedings Education and Language International Conference, 1(1).http://jurnal.unissula.ac.id/index.php/ELIC/article/download/1207/916

The second half of humanity is joining the internet. (2019, July 9). The Economist. https://www.economist.com/leaders/2019/06/08/the-second-half-of-humanity-is-joining-the-internet

Turner, A. (2023, February). February 2023 Mobile User Statistics: Discover the number of phones in the world & smartphone penetration by country or region. BankMyCell. https://www.bankmycell.com/blog/how-many-phones-are-in-the-world#part-4

UGC urges univs to continue classes online (2020, March 23). The Daily Star. https://www.thedailystar.net/city/news/ugc-urges-univs-continue-classes-online-1885063

Ur, P. (1999). A course in language teaching trainee book. Cambridge University Press.

Xu, D., Wang, H., & Wang, M. (2005). A conceptual model of personalized virtual learning environments. Expert Systems with Applications, 29(3), 525–534. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.eswa.2005.04.028

Watt, A. (2015). Fundamentals of quantitative research in the field of teaching English as a foreign language. The Praxis of English Language Teaching and Learning (PELT), 97–120. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-94-6300-112-0_6

Zhang, K., Bonk, C. J., Reynolds, T. H., & Reeves, T. C. (2020). MOOCs and open education in the Global South: Challenges, successes, and opportunities. Routledge.

Zilber, J. (2013). Smartphone apps for ESL: Finding the wheat amidst the chaff. CONTACT Magazine, 15-21.https://www.teslontario.org/uploads/pinterest/contactarticles/Apps_Zilber.pdf

Zhu, M., & Bonk, C. J. (2020). Technology tools and instructional strategies for designing and delivering MOOCs to facilitate self-monitoring of learners. Journal of Learning for Development, 7(1), 31–45. https://doi.org/10.56059/jl4d.v7i1.380