Introduction

Assessment is a vital part in the teaching and learning process and is one of the most studied topics in the field of language education. It can initially be divided into ‘traditional assessment’ and ‘authentic assessment’. Traditional assessment is mainly based on tests that are focused on measuring students’ knowledge at a particular moment during their learning process (Law & Eckes, 1995). In authentic assessment, on the other hand, students are provided with different and multiple forms of assessment to demonstrate their knowledge, skills, and achievements in authentic or real-life situations. Authentic assessment emphasizes what students know and aims at developing higher order thinking skills (Cheng & Fox, 2017; O’Malley & Valdes Pierce, 1999).

An exhaustive examination of teachers and students’ metaphors is a strong frame to explore individuals’ understanding of how metaphors shape and lead thought development and highlight the gap between concepts and reality (Botha, 2009). Metaphors help to make sense of complex natural phenomena and can be a valuable tool for unfolding and enriching the pedagogical process. The assessment purpose together with the roles of the assessment participants are varied and mainly dependent on the individual conceptualizations of assessment, as well as the social representations of those involved in the assessment process. Identifying these concepts is a key to understand teachers’ philosophies and principles underlying their teaching and assessment practices. In such an endeavor, metaphoric analysis is a sound tool to explore preservice teachers’ conceptualizations on the roles of different stakeholders in language assessment. This process always challenges teachers to find the best instruments, techniques, and tools to really assess what they have taught. Therefore, this study aims at addressing the following research questions:

1. What are the metaphors preservice teachers hold regarding the roles of teachers and students in the process of language assessment?

2. What are the metaphors preservice teachers hold regarding the process of language assessment?

Literature Review

Language assessment

When analyzing assessment, it is important to clarify a common mistake among the educational community: the employment of assessment as a synonym for testing. The concepts of assessment and testing are considerably different from each other. Testing is a part of assessment; it is just a structured and often standardized technique, while assessment is based on collecting, analyzing, and reporting data about what students know and are able to do (Bachman & Damböck, 2017). Both testing and assessment are guided by the principles of validity, reliability, practicability, authenticity, security, and washback (Cheng & Fox, 2017; Cohen, 2006; Coombe et al., 2007). Test takers are provided with exact information about the procedures and scoring of the test, whereas in assessment, the methods and techniques used to collect information and evidence vary, as well as the moment and context of application (Law & Eckes, 1995).

Assessment should mirror teaching and should consistently collect and analyse students' work through tasks that resemble real-life situations and have a positive impact on learning and teaching (Bachman & Palmer, 2000; Bailey & Heritage, 2008; Gottlieb, 2012). Assessment is tightly connected to these two processes and, as such, it is also aligned to lesson or course goals (Fulcher, 2010; Shohamy, 2001). It is perhaps one of the teachers’ most complex, important, and demanding tasks that involves both teachers and students (McNamara, 2001).

Assessment has been a widely studied topic in the field of education and various definitions and conceptions of assessment can be found. Brown (2004), for example, defines assessment as “any kind of interpreting information about student performance, collected through any of a multitude of means or practices” (p. 304). Brown’s definition emphasizes assessment to be an interpretation of evidence, to which Azis (2012) adds that teachers also have to be interpreters of the results and translate them into teaching practices. Harlen (2005) considers assessment to be a process. It involves establishing a purpose, deciding on the relevant evidence, and the best method to collect, interpret, and later deliver the evidence. For Gottlieb (2016), assessment designs should consider the characteristics of the student population, multiple pathways for students to reach their goals, the complexity of the language, instruction, and potential biases.

Assessment can be divided into three different kinds: formative, summative, and diagnostic. The purpose of formative assessment is to improve the learning process and provide students with feedback to inform their performance; therefore, it is carried out during the teaching and learning process. Summative assessment aims to verify students’ learning and is performed once the learning process is completed. In summative assessment, results are delivered to the learners in the form of grades or scores (Bachman & Palmer, 2000; Brown & Abeywickrama, 2010). Finally, diagnostic assessment, according to Yin (2008), seeks to provide a meaningful insight into the strengths and weaknesses of students, and use that information to assist the teaching process. This kind of assessment takes place usually at the beginning of the learning process.

Assessment is a form of interaction and communication; it is a teaching and learning tool and not just as an evaluation mechanism. In this sense, a difference is established between assessment of learning and assessment for learning. The former corresponds to summative assessment, and its purpose is to grade and report. The latter is related to formative assessment and has the intention of enabling students to deeply understand their own learning as well as their own expectations of the process (Gottlieb, 2016). Assessment for learning works through context-sensitive feedback and helps teachers and students to know whether that current understanding is a suitable basis for future learning. Earl (2003) identifies a third purpose: assessment as learning to refer to the process of developing and supporting metacognition and self-reflection for students, providing students with opportunities to reflect on their own mental and learning processes.

As for the purpose of assessment, and based on the information assessment seeks to gather and the methods through which that information is collected, assessment can be divided into 'traditional assessment' and 'authentic assessment' (Coombe et al., 2007; Göçen and Özdemirel, 2020). Traditional assessment is mainly based on tests. The most broadly-used tools in this kind of assessments are multiple-choice tests, true/false tests, short answers, and matching. According to Law and Eckes (1995), traditional assessment mainly consists of tests of a single occasion that only measure the students’ performance at a particular moment. In addition, traditional assessment is generally standardized and norm-referenced (Bailey, 1998). Traditional assessment only informs about the test-takers’ position in comparison to other students in the same year, but it does not give any information on their abilities or knowledge. Simonson et al. (2000) and Law and Eckes (1995) argue that this assessment technique usually focuses on skills related to the lower levels of cognition, such as memorizing and recalling of information.

Authentic assessment, on the other hand, is based on tasks and focuses on students’ ability to apply their knowledge and skills to real-life simulations (Reeves, 2000). It includes innovative assessment tools, such as open-ended questions, demonstrations, experiments, virtual simulations, projects, and portfolios. In this type of assessment, students are given the opportunity to demonstrate their knowledge, competences, and growth over time, providing them with multiple occasions to show what they have learned. Authentic assessment also takes into consideration the abilities, knowledge, and attitudes that are considered important in a working context and might benefit potential employers. To solve real-life related tasks, in opposition to what happens in traditional assessment, authentic assessment requires the practice of higher-level thinking skills in order for students to develop their language skills and proficiency.

Due to the growing understanding of the role assessment plays in instruction (Dietel et al., 1991), there has been a change in paradigms from traditional to authentic assessment. Although traditional assessment might apparently lack benefits, it presents some advantages in comparison to authentic assessment. While authentic assessment is sometimes questioned by subjectivity, reliability, and validity issues (Simonson et al., 2000), strategies used in traditional assessment ensure less subjective but at the same time provide a better basis for scores consistency and test validity. Traditional assessment is frequently time and energy-efficient, both for designing and scoring, whereas authentic assessment is usually time-consuming and difficult to carry out. Assessment is a complex process that needs to be examined in terms of the different stakeholders’’ conceptions and views on the real contribution of this process to the improvement of teaching and learning. In this regard, metaphors constitute an important research tool to examine teachers’ and students’ conceptions.

Metaphors

In essence, a metaphor is a figure of speech that consists of an implicit comparison between two unrelated ideas or objects, based on a common characteristic, where one object is expressed in terms of a different object (Alarcón et al., 2018a). Metaphors make comparisons centered on a single or multiple similarities between two concepts, overlooking any aspect of those concepts that cannot be associated to each other. The Conceptual Metaphor Theory, for example, includes in its definition of metaphor, the idea of an abstract conceptual domain conceptualized in terms of another conceptual domain, which is frequently more concrete than the first one (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980). As for the way in which they function, Gillis and Johnson (2002) and Kövecses (2010) claim that metaphors operate as mediators between the information acquired in the external world (intermental) and the internal use of the information (intramental) for knowing, making of meaning, and influencing behavior. In the process of appropriation of metaphors, the way in which we conceptualize the world culturally and cognitively is essentially changed (Dabbagh, 2017; Musolff, 2020). Metaphors have always been used in the educational field as a vehicle for explaining how language learning is used in different settings and examining new teaching strategies that can benefit learners’ academic development.

Metaphors and language education

Lakoff and Johnson (1980) state that conceptual metaphors are mental processes that provide information on the way in which our minds encode and process the world and our experiences. Carter and Pitcher (2010) claim that metaphors are linked to education because they are tools that make things understandable and may scaffold learning. In other words, they can explain new scientific theories. In this regard, Cortazzi and Jin (2020) and Geeraerts and Cuyckens (2007) state that metaphors can be effectively used as a research tool to expose and interpret perceptions and conceptualizations the stakeholders of the educational field hold related to a foreign language and the related concepts. Metaphors are widely used in the language teaching field and among language instructors. Metaphoric studies are usually focused on students’ perceptions of school related topics, such as teachers, textbooks, and the learning process (Alarcón et al., 2018b).

Budaev et al. (2015) stated that metaphors are one of the key concepts in educational theory. As constructs, metaphors are present principally in teachers’ language and reflect largely the unstated meanings of a teacher and their real disposition towards education. Consequently, metaphors are considered to play an important role as vehicles for contemplation and understanding for teachers to question their own practices and beliefs (Alarcón et al., 2018). Besides functioning as awareness raising vehicles, according to Budaev et al. (2015), metaphors are present in teachers’ discourse and can serve as a way of uncovering teachers’ hidden conceptions and beliefs. Metaphors are even regarded by some experts as a vehicle of a world view (Botha, 2009; Guerrero & Villamil, 2002) and a ‘lie detector tool’ (Budaev et al., 2015; Okere & Abah, 2019). Metaphors work differently for teachers and students because the latter are just trying to build a new mental construct, whereas the former already have their own ‘baggage[1]’. Therefore, metaphors are frames of reference of the theories underpinning education at different levels and both teachers and students should come to terms with the nature of the metaphors that hold the ideologies of a certain discipline. All metaphors come with an ideological burden that is culture-driven. For example, when writers or speakers deliberately choose certain metaphors, they may be trying to appeal to the receiver’s beliefs and emotions and to have an effect on them. The metaphor THE NATION AS FAMILY implies that the government plays the role of parents and the citizens are their children.

Studies on metaphors about assessment

Some studies related to teacher assessment reaffirm that students’ perceptions of assessment influence their approach to learning (Barnes et al., 2015; Fulmer et al., 2015). Taşgın and Kose (2015) conducted a study using metaphors with the purpose of identifying 254 pre-service classroom teachers’ perceptions about objectives and assessment. The study was qualitative in nature, and phenomenological and content analysis research methods were employed. To elicit metaphors, participants were given a questionnaire with fill-in-the-blanks exercises, which read objectives are like…, because…, and assessment is like…, because…. Pre-service teachers would have to write metaphors of their creation. The collected data were analyzed in five phases: (1) coding and sorting, (2) sample metaphor image compilation, (3) category development, (4) testing of reliability and validity, and (5) analysis of quantitative data. Sixty-nine metaphors about assessment were produced and sorted by the authors into nine different categories: 1. Assessment as a process (it is like a road, because it reaches the desired place), 2. Assessment as a tool (assessment is like an arrow, because it has an aim and indicates how far it has reached), 3. Assessment as a final element (it is like a luxury car; the individual will always benefit from education), 4. Assessment as a sensitive element (assessment is like a scale, because the weights placed on the extremes of the scale must be the same), 5. Assessment as the reach of a decision (it is like choosing a candidate to marry, because if the wrong choice is made, results will be negative), 6. Assessment as an objective element (it is like a recipe; if the necessary procedures are completed, it will give positive results), 7. Assessment as a place (assessment is like a prison, because the defendant will be processed and afterwards will be located where it belongs), 8. Assessment as a subjective element (it is like a picture, because it causes an effect and an impression, which is different for every individual), and 9. Assessment as a directive element (it is like a step, because it will take you to different places, depending on your purpose).

As Taşgın and Kose's (2015) results revealed, the highest number of metaphors produced was related to the category of assessment as a final element, while the fewest categories in terms of frequency were Assessment as a sensitive elementand Assessment as a directive element. Most of the metaphors about assessment focused on both process and product, which indicated that pre-service classroom teachers considered that assessment needed to focus not only on results but also on the process, giving relevance to the methods and techniques when assessing.

In another study conducted by Nimehchisalem and Hussin (2018) the participants were requested to create metaphors by completing the sentence: A world without assessment is…. Most of the metaphors used by students considered assessment as a guide. Some of the metaphors students produced were: A guiding star (assessment guides learning), steps of a ladder (assessment is a gradual process) and life of a free bird but forever a wanderer (life without assessment has no direction). Students also viewed assessment as a reward that motivates learning. The metaphors students developed referred to how relevant assessment is in the learning process. No assessment is like food without salt, work with no reward, a job without salary. On the contrary, a study carried out by Gök et al. (2012) demonstrated that the perception of pre-service elementary and preschool teachers about measurement and assessment was not very positive. Participants developed around 96 metaphors. Most of the participants regarded assessment as complicated. They compared assessment and measurement to a maze because it is difficult to find a way out. Participants also regarded assessment as subjective. They compared assessment to a sport match commentary because people refer to a sport match from different points of view. In terms of grades, for example, teachers are not very objective. Finally, participants regarded assessment and measurement as unnecessary. They compared both concepts to a cicada, implying that assessment and measurement are both problematic.

Method

Design of the Study

This study is qualitative in nature and consistent with phenomenology (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016) suitable for researching somewhat unknown phenomena, like identifying what metaphors preservice teachers hold about language assessment. Phenomenology examines how people describe things and experience them through their senses (Flick, 2018; Marshall & Rossman, 2016; Miles et al., 2014; van Manen, 2007).

Context

In order to observe transferability of the study, the characteristics of the context is provided in this section (Merriam & Tisdell, 2016). EFL teacher education in Chile is offered at the university level through programs that last between four and five years. To enter a teacher education program, students must sit for an entrance exam that assesses Math and Spanish essentially. No foreign language requirement is required. Over this period of five years, preservice teachers take general pedagogy courses, English language courses, EFL methodology courses, and internships. They all end up doing a one semester professional practicum and a final research piece usually known as thesis.

Participants

A convenience sample was used in this study. The participants were 49 preservice teachers from the second to the fifth year of an English Teaching Program in a Chilean university. There were 26 female, and 23 male participants. The average age range was between 20 and 34. These student-teachers have studied English and pedagogy for five years as part of their preparation to become English teachers. They are trained as future teachers of English at the university level. Preservice teachers take three semesters of EFL methodology courses (approaches, classroom management, teaching of language skills, etc.) and four internships, which all include language assessment units, which is the topic of this current study. These participants have spent around 400 hours in different schools in which English is taught. These educational establishments are samples of the three national school types: public, semi, and private; therefore, they observe and work collaboratively with their mentor teachers who have different assessment practices and views, which inevitably contribute to the shaping of preservice teachers’ professional identity. It is important to mention that the participants of the current study have been part of an educational system that is grade-oriented as grades qualify students from all educational levels to move from one level to another using a scale from one to seven, with a passing grade of 4. It is a system in which grades tend to be thought of as a synonym for assessment and testing is still very pervasive in the school system.

Instruments

An interpretation survey (Musolff, 2020) was used to collect the data and was made up of three different sections: background information, metaphor examples, and metaphor creations. The first section asked participants for background information (age, sex, and nationality). The second part of the instrument provided examples of metaphors to familiarize participants with the technique. Before beginning to answer the third part, participants were asked to carefully review the examples provided. The third section was the creation of metaphors through three statements. The statements to answer were: According to your own opinion, the teacher who assesses English learning is seen as..., In your own opinion, the assessment of English learning is like... and the last one, According to your own opinion, the students who are assessed are like... (Alarcón et al., 2015). The survey and its three statements went through expert opinions and the qualitative consistency per statement was over 90% in terms of the experts’ agreement. Since the survey statements were brief, no psychometric features were measured. Participants granted their written consent to take part in the study before answering the survey. They learned all the data was confidential, anonymous and they could withdraw from the study at any time.

Procedure

The present study was carried out in three stages: planning, data collection, and data analysis. To conduct this research, preservice teachers were contacted in person and online. They were informed that the data collection would be anonymous, but that personal data would also be required to complete the study. They signed an informed consent form. After sending the questionnaires, qualitative matrices were created to collect the data. They contained seven different sections: age, gender, school, university generation, and the three categories for the metaphors. Data saturation occurred in this study when data collection produced no new insights into the phenomenon of metaphors. Confirmability was also sought through the data collection sequence, which later allowed data to be condensed and displayed as can be seen in the results section (Flick, 2018). The researchers’ main personal assumption when analyzing the data was that the findings would unfold metaphors oriented to a traditional way of language assessment, in which testing would play a key role. To avoid biases, an external researcher audited the data matrices. In order to enhance dependability, different stages of the study are documented in the following section. These stages were audited by an outside researcher in search of accuracy in findings. However, as the research participants were small in number, no generalizable claims could be made. As a way to ensure credibility, member checking was employed for data sharing and interpretations; thus, three research participants analysed the data to see if they agreed with each other’s interpretations.

Data analysis

Metaphoric and frequency analysis were used to analyze the metaphors. Inductive content analyses were conducted in an iterative and recursive way. To ensure the inter-coder reliability, three different researchers, who were EFL teacher educators and were experienced in metaphor analysis were asked to analyze the data which resulted in the agreement index of .78. Reading and analyzing the qualitative data led to the creation of a first-level descriptive coding and a second-level analytic coding, which turned later to the more advanced qualitative interpretive approach of metaphor analysis. The details of the coding procedure are mentioned here to observe confirmability as suggested by Nassaji (2020). First level coding consisted of the basic descriptive coding of the content of metaphors and the second level coding involved categorizing, recategorizing, and condensing first level codes by connecting a dimension and its metaphors. The specific analysis was content analysis for conceptual metaphors, which consisted of the following stages: (1) pre-analysis (transcriptions were examined several times to provide thick data descriptions of possible metaphors, that is to say, qualitative information that provided insights into the participants’ metaphors), (2) coding (initial metaphor codes were set and reviewed by three researchers. Then they went back and recoded all responses again). Coding meant identifying a metaphor in the data items, searching and identifying groups of metaphors and finding relations between them. (3) classification (metaphors were classified and some were deleted based on inter-coders’ assessments of those statements that were not metaphors due to lack of comparison between two domains. Those deleted metaphors were just a basic description), and (4) metaphor categorizing (final metaphors were categorized through constant comparisons as suggested by Glaser & Strauss (1967). Researchers grouped patterns observed in the data into meaningful categories.

Results

The following are the results of the data analysis conducted.

Metaphors preservice teachers hold regarding the role of teachers in the process of language assessment.

Metaphors about the teachers’ role in the assessment process

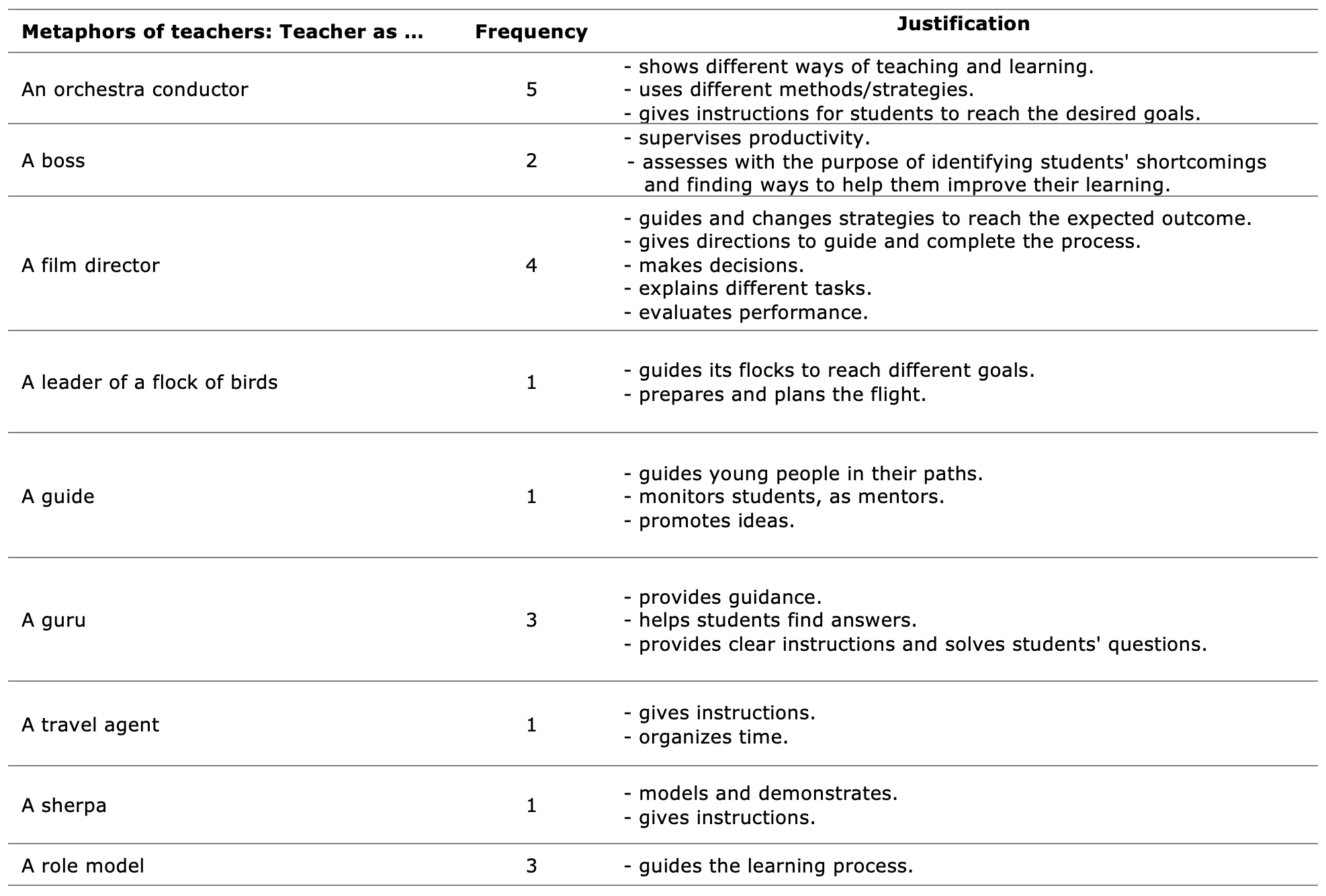

Dimension One: Teacher as a positive leader

Table 1 specifies the first dimension Teacher as a positive leader. Details of some of the metaphors are presented below.

Table 1. Teacher Metaphors for Dimension One

Table 1 shows the results of a series of metaphors regarding Teacher as a positive leader. The metaphors in this Table represent that the teacher is seen as someone who gives instructions, uses different types of teaching techniques, guides, and scaffolds students’ process of learning. Participants see the teacher as someone who is like a guide, a guru, and a travel agent. Students provided different reasons to explain their choice. For example, when the teacher monitors them, they see him/her as a guide. When the teacher helps them find answers, they see him /her as A guru. Finally, when the teacher gives instructions and/or organizes time, they see him/her as A travel agent. All these metaphors can be understood if we keep in mind that the research participants are preservice teachers who are being prepared to work in the school system at the university level and at the same time they are doing their teaching practices at different schools in which they have the opportunity of observing and interacting with in-service teachers who have to design and run assessments. They also see students’ reacting to assessments so they construct their metaphors based on their university preparation and school experience.

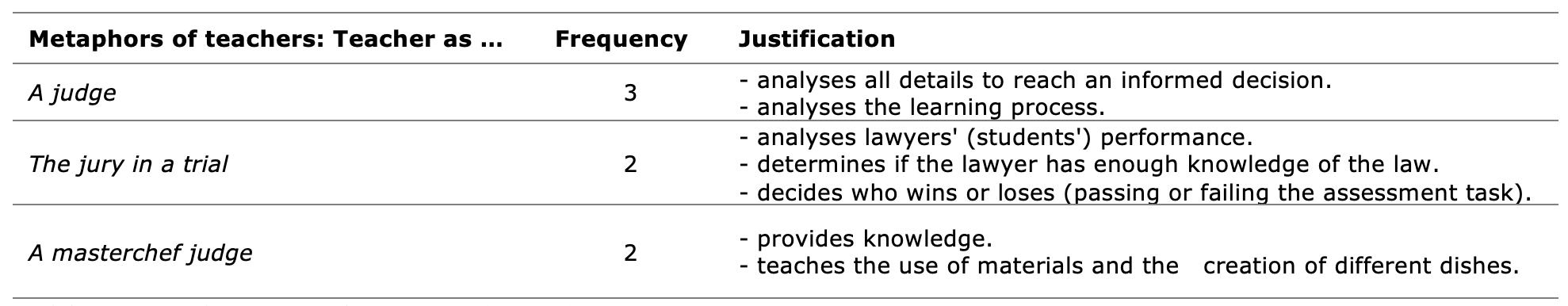

Dimension Two: Teacher as a decision-maker

Different metaphors in this category are illustrated in detail below.

Table 2. Teacher Metaphors for Dimension Two

Table 2 shows that some participants identified the Teacher as a judge and Jury in a trial. In this respect, the teacher is someone who makes decisions about students’ learning process. From the perspective of other participants, a teacher is also someone who makes decisions depending on students’ performance. Assessment puts teachers in the position of decision makers because they have to collect, analyse, and communicate student data when they do assessments. The research participants, as teacher candidates, get involved in a great deal of assessment work when they do their teaching practices because they collaborate with their mentor teachers in the design and grading of tests, quizzes, projects, and assignments.

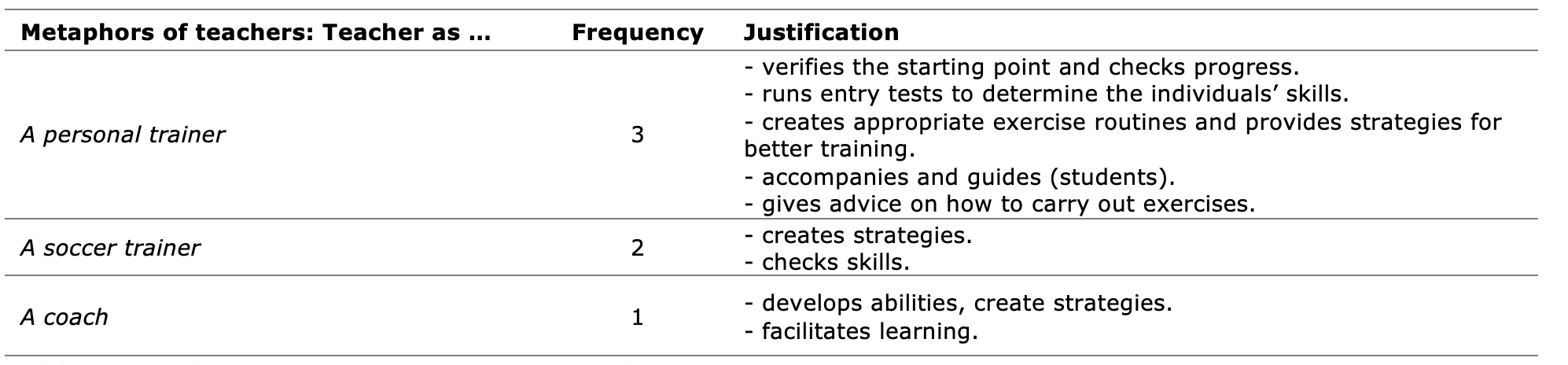

Dimension Three: Teacher as a trainer

Table 3 presents, in detail, metaphors contained in this dimension.

Table 3. Teacher Metaphors for Dimension Three

Table 3 presents the teacher as a trainer in the assessment process. Based on the participants’ opinions, they see the teacher as someone who checks progress, selects and provides appropriate strategies, and guides students to achieve their goals. The research participants acknowledge assessment in this dimension as an activity that provides evidence and data to reorient the teaching and learning process, particularly to address students’ specific language needs, which require different types of scaffolding and support.

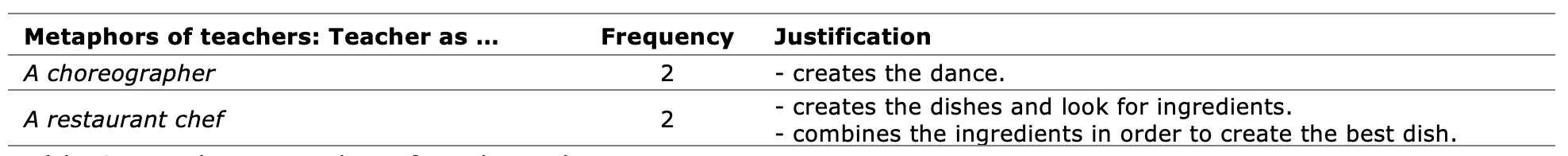

Dimension Four: Teacher as a creator

Table 4 illustrates the fourth dimension named TEACHER AS A CREATOR. Some metaphors contained in this dimension are detailed below.

Table 4. Teacher Metaphors for Dimension Four

Table 4 shows the identification of teachers as creators in the assessment process. In this context, teachers are like a carpenter and a music producer. This specific dimension highlights the important role of teachers when they have to design assessment tools for diagnostic, formative, and summative purposes trying to be consistent with what they have taught in class. Research participants identify that the assessment creation process involves making use of different strategies, resources, and materials to design an assessment that is in harmony with their own teaching. This harmony is like the one a producer or a carpenter may need to create a musical piece or an artwork, respectively so that others can enjoy them.

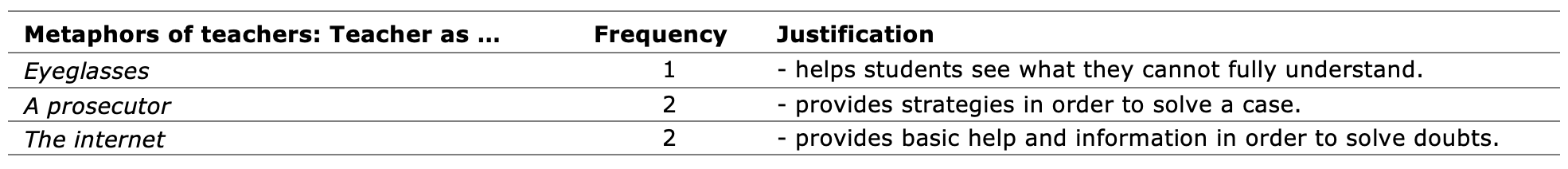

Dimension Five: Teacher as a facilitator

Table 5 specifies the sixth dimension entitled TEACHER AS A FACILITATOR. Some metaphors contained in this dimension are illustrated below in detail.

Table 5. Teacher Metaphors for Dimension Five

Table 5 presents teachers as a facilitator in the assessment process. Teachers are seen as eyeglasses in the sense that the teachers help learners see what they cannot. Besides, teachers are also like the Internet because they are a source of information, someone they can turn to get support. Research participants connect assessment with students’ lack of understanding and the support they usually need to move forward when learning. In this specific point, research participants are not just thinking of the design of formal assessments, but they are taking into consideration informal assessment, that kind of constant monitoring and reviewing of students’ work in class.

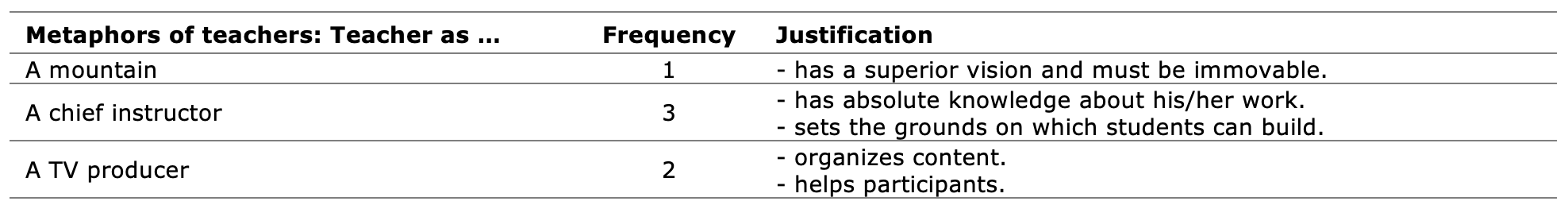

Dimension Six: Teacher as a knowledge possessor

Table 6 illustrates the seventh dimension named Teacher as a knowledge possessor. Details of the contained metaphors are presented below.

Table 6. Teacher Metaphors for Dimension Six

Table 6 presents the teacher as someone who is like a mountain and like a chief constructor. Thus, the role of the teacher is seen as someone superior in rank. The metaphors these participants have created are probably tightly connected to their professional school experiences and their own life as students who have been the recipients of some of these assessment practices.

Metaphors pre-service teachers hold regarding the role of students in the process of language assessment.

Metaphors About the Students’ Role in the Assessment Process

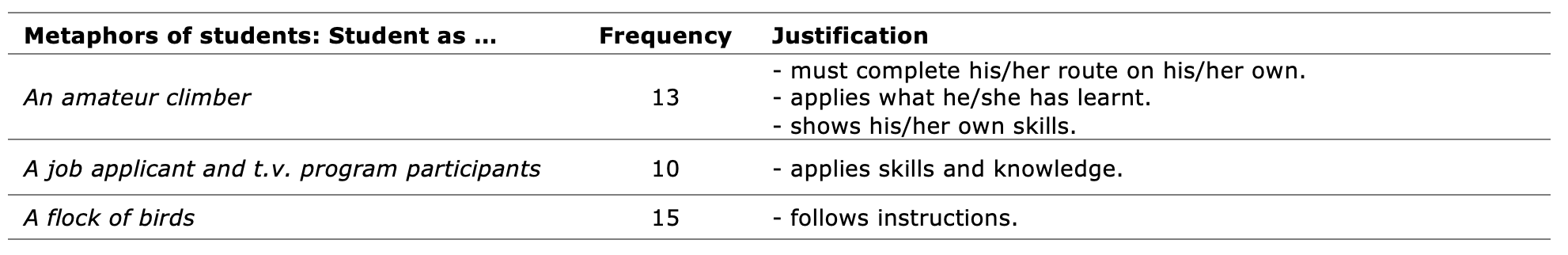

Dimension One: Student as apprentice

Table 7 specifies the first dimension about students’ role entitled STUDENT AS APPRENTICE. Metaphors of this dimension are presented in detail below.

Table 7. Student Metaphors for Dimension One

Table 7 presents students as an apprentice in the assessment process. In this dimension, participants view students as an amateur climber and as an apprentice as well. Students:

- learn and visualize which strategies to follow.

- adopt the artisan's techniques and mix them to create their own.

- ask for help to reach the desired level.

- follow instructions.

- -find strategies so that the creation process is easier.

In this dimension, research participants view language learning as a journey students have to make to get to their final destination. In this regard, they consider assessment tightly linked to learning and not as a process that is separated from teaching. Teaching, learning and assessment are intertwined and are part of a common process.

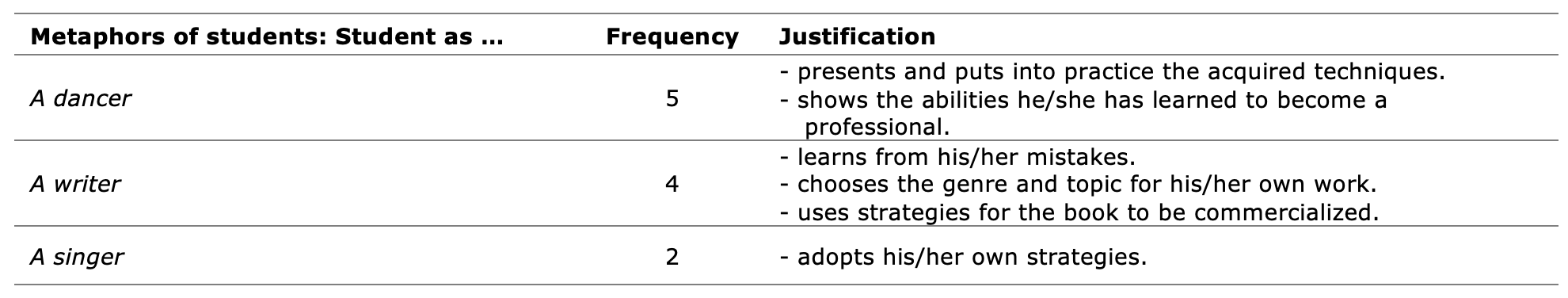

Dimension Two: Student as a developer

Table 8 presents the third dimension for students’ role, named Student as a developer. Metaphors contained in this dimension are specified and detailed below.

Table 8. Student Metaphors for Dimension Two

Table 8 presents Students as developers in the assessment process. Participants mentioned the idea of how students make learning part of their own lives. Students show their skills and their creativity and find ways to put what they have been taught into practice. Participants added that students use their time to rehearse what they have already learned, and study the content given. As a result, students can figure out in which area they are weak and seek other strategies to address the challenges of learning.

The metaphors participants have created on the role of students regard learners as agents who mainly need to be able to apply key concepts, knowledge, skills, and attitudes in ways that are consistent with current thinking in the school assessment culture in which almost nothing is said, for example, about self and peer assessment. In the context of this study it is shown that there is still a vertical relationship between teachers and students, in which the former are the ones who do all the assessment and the latter do not have a key role in this process other than being the recipient of a passing or failing grade.

The metaphors preservice teachers hold regarding the process of language assessment.

Metaphors About the Role of Assessment

Dimension One: Assessment as a process

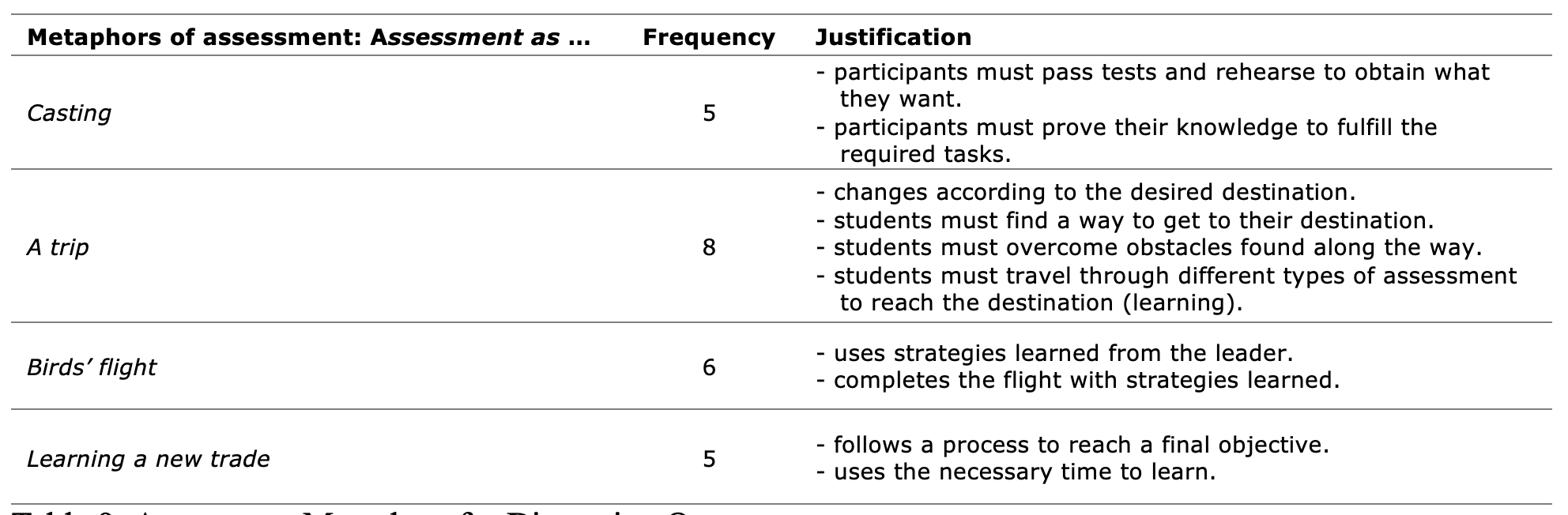

Table 9 illustrates the first dimension of language assessment entitled ASSESSMENT AS A PROCESS. Metaphors of this dimension are detailed below.

Table 9. Assessment Metaphors for Dimension One

Table 9 presents how participants view assessment. They see assessment in different metaphors, such as a casting session, a trip, bird flight, and learning a new trade. It is interesting to identify in this dimension that research participants have a clear idea of the formative role of language assessment as a process that requires feedback, reorientation, scaffolding, and the overcoming of learning obstacles. The idea of process implies that there can be changes along the way and that assessment is not a linear activity, but a process that requires a great deal of reflection on the part of both teachers and students.

Dimension Two: Assessment as a product

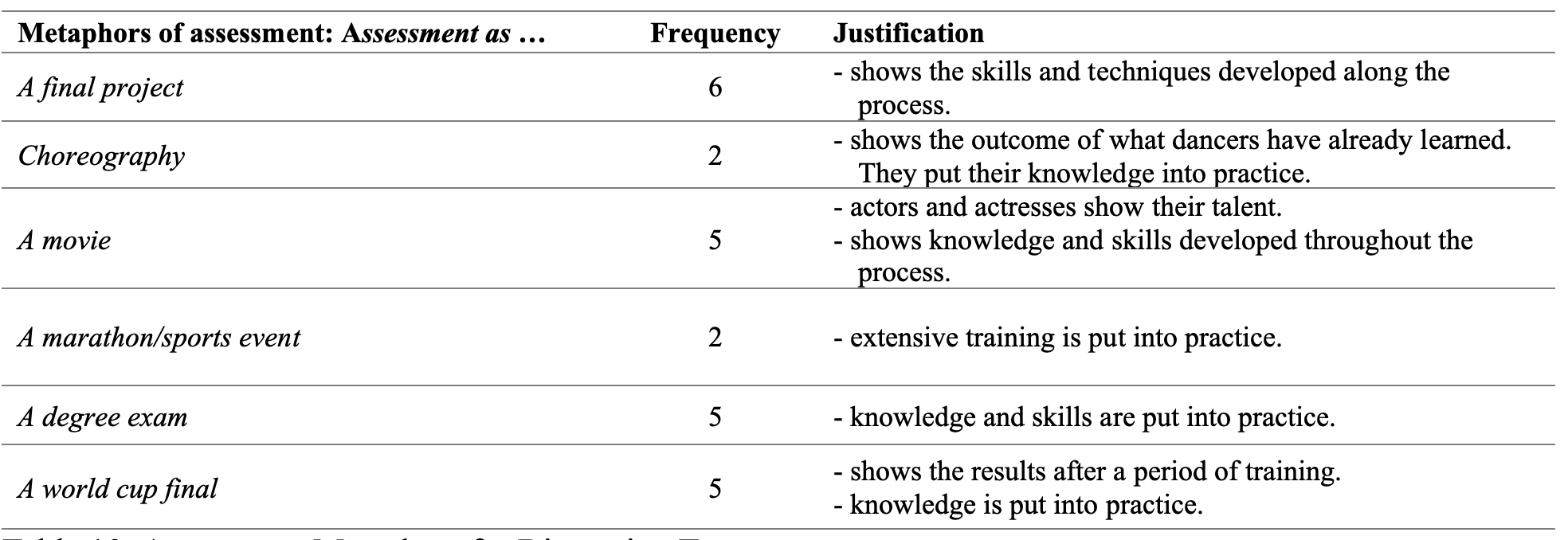

Table 10 illustrates the second dimension of assessment process, entitled ASSESSMENT AS A PRODUCT. Metaphors belonging to this dimension are detailed below.

Table 10. Assessment Metaphors for Dimension Two

Table 10 shows how participants identify Assessment as a product. In this dimension assessment importance is the ending, the product itself, the final goal after a process. This product considers context, the implementation of tactics and strategies, previous revision, and the abilities students previously acquired. Participants presented the final version of all types of products as the assessment. As preservice teachers, participants do their field experiences in schools where assessment as a product has a very important weight or in other schools in which stakeholders struggle to keep a balance between assessment as a process and assessment as a product. Historically, the (Nationality) English teaching has relied heavily on testing and assessment as a product, but over the last two decades the school system is moving slowly towards formative assessment and assessment as a process, in an educational context that still uses standardized testing to measure learning quality (Cronquist & Fiszbein, 2017).

Trying to learn a foreign language in a Spanish-speaking context is always a hard and complex task for both teachers and students, particularly, for those countries that are geographically far away from English-speaking countries. Technology can certainly help a lot; however, learning a foreign language is intrinsically a human face-to-face communication, in which the construction of safe and friendly classroom climates is vital and contextually bound. In addition to this, foreign language assessment is a triple effort for students, preservice-teachers and in-service teachers, in a school system that has historically been invaded by paper and pencil tests and that is trying to embrace classroom and formative assessment slowly. It is then no surprise that preservice and in-service teachers strive for professional foreign classroom assessment development. The assessment as a process or product division unfolds the tensions preservice teachers still experience when they have to assess their own students formatively or summatively in school contexts in which grades have an important role for the different stakeholders.

Preservice teachers move in scenarios in which school administrators and parents want learners to academically ‘succeed’ by obtaining good grades because these are the ones that allow their pupils to go from one educational level to another; on the other hand, the state sees standardized testing as a tool to monitor and supervise students’ learning progress and as a measure of what is going on with quality education.

Discussion

In this study, conceptions about the role of teachers, students, and assessment held by preservice teachers were investigated through the application of a metaphor questionnaire. To analyze the results, metaphors were organized into three major dimensions: (1) teacher, (2) student, and (3) assessment.

The current group of research participants were surveyed on metaphors at a stage in their university teaching preparation in which they were both learning a foreign language and pedagogical strategies and techniques to teach the language to students of different ages. This scenario contributes to the shaping of different conceptions and beliefs on learning, teaching, and assessment that similar studies (Nimehchisalem & Hussin, 2018; Ridenour, 2020) have shown and explored in the past. Preservice teachers’ metaphors in the current study indicated that metaphors might lead to beliefs in action, and some of them might perpetuate stereotypes that could limit teachers’ learning. Therefore, metaphor analysis can be considered as an important tool to instigate preservice teachers’ knowledge of themselves and that of their students and classroom experiences. The relevance of this analysis aligns with the idea that metaphors are constructs through which minds process the world and our experiences (Lakoff & Johnson, 1980).

Interestingly, Chilean participants regarded teachers as agents who perform different and several roles in assessment (7 roles). Students also assumed fewer roles (just 2 in total) than teachers did in assessment, and the act of assessing itself was clearly dichotomous and extreme (process and product). Of the two key agents in assessment in this study, i.e., teachers and students, just the former are placed themselves in roles of power and that of knowledge possessors, while the latter assume much more passive roles in language assessment. Dichotomous and extreme conceptions on teaching, learning, and assessment have also been found in other studies, like Casebeer (2015), who identified metaphors associated to growth and production. Teachers were more inclined to the use of collaborative strategies and aimed at helping students make sense of their own learning. While students unfolded more controlled and structured ways of learning and assessment. Another example comes from Taşgın and Köse’s (2015) study on the nine categories of metaphors on assessment produced by 254 preservice teachers. They concluded that there exist extreme oriented metaphors (assessment as a final element and assessment as a process); however, there were also categories of metaphors that were in between these two extremes (assessment as a sensitive element, for example) and offered another dimension of assessment.

As to the role of a teacher, participants saw teachers in different roles. Based on the proposed metaphors, such as the Teacher as an orchestra conductor, a boss, and a film director, it can be concluded that students see the teacher as a positive leader. In this respect, participants saw the teacher as a knowledgeable person who can guide students, identify their weaknesses, and select appropriate strategies based on those weaknesses. Under the leader role, the teacher has no longer a directive role, but one that empowers students and promotes collaboration among peers. According to Wynne (2011), “effective teacher leadership involves a move away from top-down, hierarchical modes of functioning and a move toward shared decision-making, teamwork, and community” (p. 2). This means that teachers are no longer someone who just gives instructions and tells students what to do; on the contrary, they are the ones who help students construct their own knowledge. Along the same lines, the study conducted by Ridenour (2020) signals that teachers and students need to be working alongside each other to help learners achieve success and their teaching to be considered effective.

Participants also saw the teacher as a guide. They described teachers as a guru, a travel agent, and Sherpa. As a guide, the teacher was seen as someone who modeled lessons and created an environment in which most students could participate. As Beresaluce et al. (2014) declare, the role of a teacher as a guide or advisor in the educational process, guides learners so that they can learn on their own. The teacher acts as a guide who supervises and scaffolds students so that they can move progressively towards a goal. In this regard, participants view language teachers performing active, varied, and dynamic roles in assessment and teaching, i.e., as agents who can conduct multitasks and perform one role or another, depending on the lesson aims, the students’ needs, and the contexts in which they are working. Teachers are seen as agents who are able to move along a continuum that may need guiding, on one point, and supervising on another with many other assessment and teaching roles in between. This is also linked to the idea that assessment has diagnostic, formative, and summative purposes in the teaching and learning process, as suggested by Gottlieb (2016). These different assessment purposes put teachers in either directive or more guiding teaching positions

According to the metaphors elicited from responses to the administered questionnaire, participants also saw the teacher as a decision maker. They use metaphors such as a judge, the jury in a trail, and a casting director. Hopfenbeck (2018) affirms that the role of a teacher as a decision maker is one in which the teacher makes decisions about different aspects of the students’ learning process, e.g., decisions about assessment, strategies, and tasks. In this context, the teacher needs to know how to interpret data regarding students’ knowledge and decide what tasks are the most appropriate to complete in order to consolidate students’ learning. Participants also perceived the teacher as a trainer. They used the following metaphors: a personal trainer, a soccer trainer, and a coach. As a trainer, the teacher is someone who can verify the students' background knowledge to select strategies that can help them get the most throughout their learning process. The teacher accompanies and guides students, advising them on further practice and helping them to face new challenges.

Students also perceived the role of the teacher as a creator. They used metaphors such as A choreographer and a restaurant chef. This means that, in the field of assessment, the teacher needs to be able to create a plan that includes different methods and techniques. Besides, according to Bovill et al. (2011), the role of the teacher implies the creation and adaptation of tasks, different types of instruments and also rubrics to assess their students. In the opinion of McLaughlin (2019), teachers as creators can design a better learning environment that encourages students’ self-reflection.

Another role of the teacher based on students’ metaphors was the one of a facilitators. Some of the metaphors the participants used are: The teacher as eyeglasses, a prosecutor, and the internet. Participants valued the help and the strategies that teachers offered students to acquire knowledge and competences. Students emphasized how teachers created a safer environment for the assessment process, something that could lead students to learn more efficiently. According to Srivastava (2014), “a facilitator should offer insights, remain neutral, listen to learners’ views, and be curious about how their reasoning differs from others, so that they can be helped for a productive conversation” (p. 180).

Finally, students also conceptualized the Teacher as a knowledge possessor. Teachers were compared to a chief constructor and a TV producer. As Guerriero (2014) states, the teacher as a knowledge possessor is expected to process and evaluate the new knowledge that students acquire through the assessment process and use it as a tool to improve their professional practice.

As teachers have to play different roles as assessors, the language assessment process also has either a traditional or an authentic orientation, which makes stakeholders assume different roles. Coombe et al. (2007) also pointed out the difference between traditional and authentic assessment, which puts both teachers and students in different roles in the teaching and learning process. When students are doing a test, the teacher tends to assume a more directive, judging and knowledge possessor role and students are more constrained by a role that requires them to basically retrieve knowledge to answer a test correctly. However, when students work on a more authentic assessment task such as an oral presentation or a video creation activity, they immediately assume a more participatory and contributing role, while teachers play more facilitating, guiding and supportive roles in assessment. Therefore, metaphor construction may also be influenced by the type of assessment both teachers and students are usually exposed to the most.

The role of the teacher as a leader is also seen in the study of Brown (2002), who interviewed 30 preservice teachers and concluded that assessment always implies that someone is in a role of power because they possess knowledge that others do not have. Wynne (2011) also explored the role of the teacher as a leader, finding out that effective teacher leadership involves a change in teacher-students dynamics. There is a switch from a hierarchical mode of functioning to a system that thrives on decision-making and teamwork as a learning community. According to Mooney's (1994) study titled Teachers as Leaders: Hope for the Future, teachers are presented as risk-takers and role models who inspire a vision, like teamwork, and naturally nurture the talent and energy of colleagues and students.

As to the metaphors pre-service teachers hold regarding the role of students in the process of language assessment, pre-service teachers conceptualized the students as an apprentice. They perceived themselves as amateur climbers, job applicants, and flocks of birds. Students as apprentice require leadership. They also need observation and feedback. Students need leadership and guidance on how to follow instructions, and the way they adopt strategies to fulfill their learning needs. This depiction of the students’ role in learning and assessment is similar to a metaphor explored by Ridenour (2020), in which the role of students would be one that requires them to follow, mimic and recreate behaviors modelled and exemplified by their teachers.

Students were also seen as developers. They used the following metaphors to describe this role: dancers, writers, and singers. As a rule of thumb, students take part in their learning, they show their skills and creativity by putting into practice what they are taught. There is feedback involved, from the teacher and peers; however, students review the content and create their strategies with the information given using their time to develop new ways to complete the assessment process. Students in the assessment process are guided by teachers. For Mooney (1994), students need directions and instructions to examine the effectiveness of assessment; however, students can create effective learning choices on their own and complete the assessment process.

The studies by Taşgın and Köse (2015) and Nimehchisalem and Hussin (2018) presented in the theoretical framework and this current study, regarding the different metaphors on assessment participants are able to build, show that metaphors are context-bound. Preservice teachers construct metaphors on assessment depending on the educational system they have experienced, and more specifically, on the school type and context they are currently involved in. Therefore, a school’s or a mentor teacher’s assessment practices may have a key role on shaping or reshaping preservice teachers’ own metaphors, explaining a wide variety of metaphors that participants constructed, which may have either a positive or negative meaning.

As to the metaphors preservice teachers hold regarding the process of language assessment, in the first dimension, i.e., Assessment as a process, students mentioned the idea of learning through stages, which was compared to a casting session, a trip, a bird flight, and learning a new trade. Assessment was shown as a process in which students follow instructions and must rehearse little by little to reach a final goal. Students at this stage show everything they have learned and how they have progressed. Showing what they are learning in the process is what they want to achieve, because they want to demonstrate the effort they have made to reach a final goal. Toth (2018) described assessment as a process by saying that to get to a particular outcome or goal, a series of steps is needed. However, as to the dimension Assessment as a product, assessment relies on the end product. Assessment as a product is compared to a choreography, a movie, a marathon event, a degree exam, and a World Cup Final. This product considers the context, strategies, previous revisions, and the abilities students have previously acquired. Toth (2018) refers to Assessment as a product, focusing on the outcome and the final creation that comes after the previous step-by-step process. This process is represented in education by test results, oral presentations, visual displays, physical or digital models, and essays, among others. As mentioned before, the metaphors that participants create regarding assessment are highly influenced by their background (Nimehchisalem & Hussin, 2018). Interestingly, when it comes to assessment, the metaphors studied by Nimehchisalem and Hussin (2018) put emphasis on assessment as a guide, a tool that directs both the learners and the instructor’s development, while in the present study, the role of guiding was only assigned to teachers in the metaphors.

Conclusion

From the present study, different conclusions can be drawn. First, it is interesting to go deeper into how participants view the roles of teachers and students in the process of language assessment through different types of metaphors. As to the role of the teacher, the metaphors produced by the participants such as leader, decision maker, facilitator, creator, among others, show that the teacher plays very different and significant roles in the process of language assessment. Each role is played in different stages of the learning process and also in different moments over the lesson. Thus, from the results, it can be concluded that the teacher’s role in assessment is considered to be dynamic by the participants and these roles probably change depending on the type of technique or instrument teachers employ to assess students and whether formative or summative assessment is emphasized along the process. Teachers’ roles in assessment move within a continuum in which, on one side, the traditional metaphor of the teacher as a knowledge possessor still plays a part in assessment and, on the other side, the constructivist metaphor of the Teacher as a facilitator in assessment is also seen by the participants. Other metaphors are in between these two extremes and the complexity and importance of language assessment for different stakeholders probably make teachers accountable for designing, implementing, and evaluating assessment tools that can capture not only students’ learning achievements, but also their interests, needs, affects and differences.

As to the role of students in the process of language assessment, it can be concluded that students are perceived in different roles throughout the process. At the beginning, they are perceived as apprentice because they depend more on the teacher and require leadership, observation, support, and feedback. In the last stages of the process, students are viewed as creators who are supposed to have a more independent role. They take active roles in their learning process. They are also supposed to build their own knowledge and put what they have been taught into practice. In other words, they are able to learn and use the strategies they have been taught.

Finally regarding, the metaphors preservice teachers hold regarding language assessment as a process and as a product, students used metaphors such as: a casting session, bird flights, a trip, for assessment as a process and a final project, a movie, and a degree exam for assessment as a product. This shows that the process of language assessment is full of different stages that are required to reach a final goal.

As a conclusion, the implications that this study has for the teaching and learning of English and the training of English teachers is the examination of how preservice teachers perceive the roles of teachers, students, and assessment in the Chilean educational system; and how these perceived roles can shape and impact the teaching practices. It is crucial for preservice and in-service teachers to be aware of their own conceptions about assessment and its factors. They can reflect and put their pedagogical practices into perspective, and become aware that both teachers and students, as human beings and key stakeholders, cannot be placed into rigid, non-dynamic assessment roles.

Regarding limitations, it was concluded that increasing the amount of background information from interviewees may have enhanced the understanding of the metaphors, since the formal exercise of constructing metaphors is not easy as it seems for interviewees because they are being pushed to think consciously of a phenomenon they tend to use unconsciously in everyday life. This research can be expanded in the future by examining in-service teachers’ metaphor creation processes to understand how the professional experience factor affects the metaphors and justifications they produce.

Further research should be conducted to identify how the metaphors preservice teachers produce manifest in the actual design of language assessment instruments and in the work they do with the students in the classroom. It would also be beneficial to compare the metaphors generated by preservice teachers with those produced by their tutors at the university and their mentor teachers in the schools.

References

Alarcón, P., Díaz, C., & Vergara, J. (2015). Chilean preservice teachers’ metaphors about the role of teachers as professionals. In W. Wan & G. Low, Elicited metaphor analysis in educational discourse, (pp. 289-314).

Alarcón, P., Díaz, C., Vergara, J., Vásquez, V., & Torres, C. (2018a). Análisis de metáforas conceptuales sobre la imagen social del profesorado en estudiantes de pedagogía. [Conceptual metaphor analysis of teachers’ social images among pre-service teachers]. Onomázein. Revista de lingüística, filología y traducción, 40, 1-27.

Alarcón, P., Díaz, C., & Vásquez, V. (2018b). Un análisis de columnas de opinión desde la metáfora conceptual. [An analysis of opinion columns from the conceptual metaphor perspective]. Signo y Pensamiento, 37(73), 1-15.

Azis, A. (2012). Teachers’ conceptions and use of assessment in student learning. Indonesian Journal of Applied Linguistics, 2(1), 40-52.

Bachman, L. F., & Palmer, A. S. (2000). Language testing in practice: Designing and developing useful language tests. Oxford University Press.

Bachman, L., & Damböck, B. (2017). Language assessment for classroom teachers: Why, when, what, and how?. Oxford University Press.

Bailey, K. M. (1998). Learning about language assessment: Dilemmas, decisions, and directions. Heinle & Heinle.

Bailey, A. L., & Heritage, M. (2008). Formative assessment for literacy, grades K-6: Building reading and academic language skills across the curriculum. Corwin.

Barnes, N., Fives, H., & Dacey, C. M. (2015). Teachers’ beliefs about assessment. In H. Fives & M. G. Gill (Eds.), International handbook of research on teacher beliefs (pp. 284-300). Routledge.

Beresaluce, R., Peiró, S., & Ramos, C. (2014). El profesor como guía-orientador. Un modelo docente [The teacher as an orienting guide. A teaching model]. In M. T. Tortosa Ybáñez, J. D. Alvarez Teruel & N. Pellin Buades (Eds.), XII Jornades de sarxes D’investigació en docència universitària: El reconeixement docent: Innovar i investigar amb criteris de qualitat (pp. 857-870). Universidad de Alicante.

Botha, E. (2009). Why metaphor matters in education. South African Journal of Education, 29(4), 431-444. https://doi.org/10.15700/saje.v29n4a287

Bovill, C., Cook-Sather, A., & Felten, P. (2011). Students as co-creators of teaching approaches, course design and curricula: Implications for academic developers. International Journal for Academic Development, 16(2), 133-145. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/1360144X.2011.568690

Brown, G. T. L. (2002). Teachers' conceptions of assessment [Unpublished doctoral dissertation], University of Auckland. http://repositorio.minedu.gob.pe/handle/20.500.12799/2866

Brown, G. T. L. (2004). Teachers' conceptions of assessment: Implications for policy and professional development. Assessment in Education, 11(3), 301-318. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594042000304609

Brown, H. D., & Abeywickrama, P. (2010) Language assessment: Principles and practices. Pearson.

Budaev, E. V., Prokopievich, C. A., & Filippovna, T. G. (2015). Conceptual metaphor in educational discourse. Biosciences Biotechnology Research Asia, 12(1), 561-567. http://www.biotech-asia.org/vol12no1/conceptual-metaphor-in-educational-discourse

Carter, S., & Pitcher, R. (2010). Extended metaphors for pedagogy: Using sameness and difference. Teaching in higher education, 15(5), 579-589. https://doi.org/10.1080/13562517.2010.491904

Casebeer, D. (2015). Mapping preservice teachers' metaphors of teaching and learning. International Journal of Learning, Teaching and Educational Research, 12(3), 3-23. https://www.ijlter.org/index.php/ijlter/article/view/392/178

Cheng, L., & Fox, J. (2017). Assessment in the language classroom. Macmillan.

Cohen, A. D. (2006). The coming of age of research on test-taking strategies. Language Assessment Quarterly, 3(4), 307-331. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434300701333129

Coombe, C. A., Folse, K., & Hubley, N. (2007). A practical guide to assessing English language learners. University of Michigan.

Cortazzi, M., & Jin, L. (2020). Elicited metaphor analysis: Researching teaching and learning. In M. T. M. Ward & S. Delamont (Eds.),Handbook of qualitative research in education (pp. 488-505). Edward Elgar.

Cronquist, K., & Fiszbein, A. (2017). El aprendizaje del inglés en América Latina [English learning in Latin America]. El diálogo.

Dabbagh, A. (2017). Cultural linguistics as an investigative framework for paremiology: Comparing time in English and Persian. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 27(3), 577-595. https://doi.org/10.1111/ijal.12162

Dietel, R. J., Herman, J. L., & Knuth, R. A. (1991). What does research say about assessment?. North Central Regional Education Laboratory.

Earl, L. M. (2003). Assessment as learning: Using classroom assessment to maximize student learning. Corwin.

Flick, U. (2018). An introduction to qualitative research (4th ed.). Sage.

Fulcher, G. (2010). Practical language testing. Hodder Education.

Fulmer, G. W., Lee, I. C., & Tan, K. H. (2015). Multi-level model of contextual factors and teachers’ assessment practices: An integrative review of research. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy, and Practice, 22(4), 475-494. https://doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2015.1017445

Geeraerts, D., & Cuyckens, H. (2007). Introducing cognitive linguistics. In D. Geeraerts & H. Cuyckens (Eds.). The Oxford handbook of cognitive linguistics (pp. 3-21). Oxford University Press.

Gillis, C., & Johnson, C. L. (2002). Metaphor as renewal: re-imagining our professional selves. The English Journal, 91(6), 37-43. https://doi.org/10.2307/821814

Glaser, B. G., & Strauss, A. L. (1967). The discovery of grounded theory: Strategies for qualitative research. Aldine.

Göçen, G., & Özdemirel A. Y. (2020). Turkish culture in the metaphors and drawings by learners of Turkish as a foreign language. Participatory Educational Research, 7(1), 80-110. https://doi.org/10.17275/per.20.6.7.1

Gök, B., Erdogan, O., Altinkaynak, S. O., & Erdogan, T. (2012). Investigation of pre-service teachers’ perceptions about concept of measurement and assessment through metaphor analysis. Procedia-Social and Behavioral Sciences. 46. 1997-2003. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.05.417

Gottlieb, M. (2012). Common language assessment for English learners. Solution Tree.

Gottlieb, M. (2016). Assessing English language learners: Bridges to educational equity (2nd ed). Corwin.

Guerrero, M. C. M. de, & Villamil, O. S. (2002). Metaphorical conceptualizations of ESL teaching and learning. Language Teaching Research, 6(2), 95-120. https://doi.org/10.1191/1362168802lr101oa

Guerriero, S. (2014). Teachers’ pedagogical knowledge and the teaching profession: Background report and project objectives. Organization for Economic Co-operation and Development. https://www.oecd.org/education/ceri/Background_document_to_Symposium_ITEL-FINAL.pdf

Harlen, W. (2005). Teachers’ summative practice and assessment for learning-tensions and synergies. The Curriculum Journal, 16(2), 207-223. https://doi.org/10.1080/09585170500136093

Hopfenbeck, T. N. (2018). ‘Assessors for learning’: Understanding teachers in contexts. Assessment in Education: Principles, Policy & Practice, 25(5), 439-441. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/0969594X.2018.1528684

Kövecses, Z. (2010). Metaphor: A practical introduction (2nd ed). Oxford University Press.

Lakoff, G., & Johnson, M. (1980). Metaphors we live by. The University of Chicago Press.

Law, B., & Eckes, M. (1995). Assessment and ESL On the yellow big road to the withered of Oz: A handbook for K-12 teachers. Peguis.

Marshall, C., & Rossman, G. B. (2016). Designing qualitative research. Sage.

Merriam, S., & Tisdell, E. J. (2016). Qualitative research. A guide to design an implementation. Jossey-Bass.

McLaughlin, C. (2019, January 8). Teachers as learners and creators of knowledge–an essential for change and development. The education world forum. https://www.theewf.org/research/2019/teachers-as-learners-and-creators-of-knowledge-an-essential-for-change-and-development

McNamara, T. (2001). Language assessment as social practice: Challenges for research. Language Testing, 18(4), 333-349. https://doi.org/10.1177/026553220101800402

Miles, M. B., Huberman, A. M., & Saldaña, J. (2014). Qualitative data analysis. A methods sourcebook. Sage.

Mooney, T. (1994). Teachers as leaders: Hope for the future. National Commission on Excellence in Education. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED380407.pdf

Musolff, A. (2020). Political metaphor in world Englishes. World Englishes, 39(4), 667-680. https://doi.org/10.1111/weng.12498

Nassaji, H. (2020). Good qualitative research. Language Teaching Research, 24(4), 427–431 https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168820941288

Nimehchisalem, V., & Hussin, N. I. S. M. (2018). Postgraduate students’ conception of language assessment. Language Testing in Asia, 8(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1186/s40468-018-0066-3

Okere, M. C., & Abah, E. E. (2019). The workings of metaphor in language discourse. Pan-African Journal of Humanities and Social Sciences, 1(6), 198-202. https://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.3353845

O’Malley, M. J., & Valdes Pierce, L. (1999). Authentic assessment for English language learners: Practical approaches for Teachers. Addison-Weasley.

Reeves, T. C. (2000). Alternative assessment approaches for online learning environments in higher education. Educational Computing Research, 3(1), 101-111. https://doi.org/10.2190/GYMQ-78FA-WMTX-J06C

Ridenour, M. (2020) Teachers are: Analyzing the metaphors of pre-service educators. Northwest Journal of Teacher Education, 5(1) , 1-13. https://doi.org/10.15760/nwjte.2020.15.1.4

Shohamy, E. (2001). The power of tests: A critical perspective on the uses of language tests. Pearson.

Simonson, M., Smaldino, S., Albright, M., & Zvacek, S. (2000). Teaching and learning at a distance: Foundations of distance education. Prentice-Hall.

Srivastava, T. K. (2014). Teacher as facilitator: A requisite during foundation years of medical curriculum. National Journal of Physiology, Pharmacy & Pharmacology, 4(3), 179-18. http://dx.doi.org/10.5455/njppp.2014.4.270620141

Taşgın, G. A., & Köse, E. (2015). Preservice classroom teachers' metaphors about objective and evaluation. Hacettepe University Journal of Education, 30(3), 116-130.

Toth, P. (2018, February 5). Process versus product: The knowledge building connection. The Learning Exchange. https://thelearningexchange.ca/process-versus-product-knowledge-building-connection

van Manen, M. (2007). Phenomenology of practice. Phenomenology & Practice, 1(1), 11–30. https://doi.org/10.29173/pandpr19803

Wynne, J. (2011). Teachers as leaders in education reform [ED462376] ERIC. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=ED462376

Yin, M. (2008). Diagnosing foreign language proficiency: The interface between learning and assessment [Review of the book by the same name by J. C. Alderson]. Language Assessment Quarterly, 5(1), 77-81. https://doi.org/10.1080/15434300701595637

[1] Background knowledge and experiences