Introduction

English proficiency is one of the terms that is frequently used by researchers, teachers, and learners of the English language. It can be used as a basic reference in designing and developing instructional materials for an English course or subject, as well as a measure of success at the conclusion of the teaching and learning process. The term ‘English proficiency’ is commonly applied to those whose first language is not English and it is measured by standardized tests such as IELTS, TOEFL, and TOEIC (Ortmeier-Hooper & Ruecker, 2016). Harsch (2017) explains, “It is generally recognized that the concept of proficiency in a second or foreign language comprises the aspects of being able to do something with the language (‘knowing how’) as well as knowing about it (‘knowing what’)” (p. 250). Such a concept of proficiency underlies the Council of Europe (2001) statement that proficiency refers to “what someone can do/knows … (p. 183)” regarding the application of the target language in the real world. In other words, English proficiency should depict ones’ ability and knowledge in utilizing English in actual situations. To assess such ability and knowledge, English standardized tests are commonly employed, but it is also important to understand that English proficiency encompasses communicative abilities, knowledge systems, and skills (Canale, 1983).

In Thailand English proficiency has always been the concern of English language teaching and learning since the 1980s. Such concern is rising as annual reports from international educational institutions, such as Educational Testing Service (ETS) and Education First (EF), indicate low levels of English proficiency for test takers. In ETS’s reports, Thailand was consistently ranked among poor-performing countries (2012-2017) on the Test of English for International Communication (TOEIC); the average scores were low on listening, but much lower on reading. Education First (2020) has also reported a very low level of Thailand EFL students’ English proficiency from 2011 to 2016 and from 2019 to 2020. In 2020, the average scores of Thailand EFL students were ranked twentieth out of 24 countries in Asia.

The Ministry of Education of Thailand has been implementing various educational initiatives to address the issue of Thailand students’ low English proficiency. One of the initiatives is the adoption of the Common European Framework of Reference (CEFR) for Languages, which was officially declared in 2014 (Ketamon et al., 2018). The framework serves as guidelines for material development and assessment, such as textbooks, syllabus, curriculum guidelines, examinations, and so forth, across educational contexts around the globe. On a global scale, the CEFR conceptualizes English proficiency into three categories and six levels, including Proficient Users (C1 and C2), Independent Users (B1 and B2), and Basic Users (A1 and A2). Schools and universities in Thailand are advised to benchmark their students’ English proficiency levels in CEFR. Each level of CEFR is interpreted as the ability of each level of formal schooling. A1 is interpreted to be the ability of primary school students; A2 is the ability of junior high schools; B1 is for senior high schools, and B2 is the ability of university students. C1 and C2 are interpreted to be the ability of near-native or native English speakers (Ministry of Education, 2014). Such interpretations may assist schools and universities in achieving the targeted level of English proficiency. Nevertheless, a recent study by Waluyo (2019) found that the English proficiency levels of most Thailand first-year undergraduate students were at A1 and A2 levels (basic users of English) in CEFR. This indicates that the low level of English proficiency among Thailand EFL students remains a problem to be solved. Undeniably, the level of students’ English proficiency can be an indicator of their success in learning English; thus, investigating influential factors in students’ English learning such as self-regulated learning (SRL) strategies can be useful in addressing the issue of students’ low proficiency levels.

SRL strategies refer to students’ learning behaviors to acquire information or skills involving metacognition, strategic action, and learning motivation (Boekaerts & Corno, 2005; Perry et al., 2006; Zimmerman & Pons, 1986). Many studies have highlighted SRL strategies as factors contributing to successful English learning. These studies examined the role of SRL strategies in different academic environments. One of the key findings suggests the crucial role of these strategies on students’ English learning achievement (e.g., Bai et al., 2014; Seker, 2016).

Studies on SRL strategies and English learning achievements have been growing in the literature, but there is a limited number of studies examining SRL strategies and using the CEFR as the indicator of English proficiency levels (e.g., Cho & Ma, 2018; Fukuda, 2018). In the Thailand context, for instance, Pratotep and Chinwono (2008) explored students’ SRL strategies and their English reading comprehension. Moreover, Samruayruen et al. (2013) and Woottipong (2019) investigated the effects of SRL strategies in the context of online learning environments. To address such gaps, the present study investigated students’ SRL strategies with different English proficiency based on CEFR levels. This study was guided by two following research questions:

- How different is Thailand EFL students’ use of SRL strategies by English proficiency level?

- How do Thailand EFL students’ SRL strategies correlate with their English proficiency?

Literature Review

Self-regulated learning (SRL) strategies

Self-regulated learning is defined as a complex, interactive process that involves not only cognitive but also motivational self-regulation, which encourages students to be proactive in their learning process (Boekaerts, 1997; Zimmerman, 1990 & 2002). As it requires students to self-regulate their own learning, the process happens largely outside the classroom in an unsupervised environment, in which self-initiated and self-managed learning are required to obtain desired academic outcomes (Bjork et al., 2013). Self-regulated learning (SRL) has been identified as one of the non-cognitive skills that can affect students’ academic outcomes (Rosen et al., 2010). Non-cognitive skills refer to students’ academic behaviors, mindsets, perseverance, learning strategies, and social-emotional skills (Kyllonen, 2012; Richardson et al., 2012). The importance of having students able to apply self-regulated learning in their foreign language learning lies in the need to spend time and practice beyond class hours when acquiring a foreign language. To achieve success, students must be personally involved, motivated, and eager to self-regulate their own learning, even when boredom, procrastination, and uncontrolled emotions occur (Nakata, 2010).

Specifically, SRL strategies are the actions that students employ to acquire information or skills including Goal Setting and Planning, Organizing and Transforming, Seeking Information, Keeping Records and Monitoring, Environmental Structuring, Rehearsing and Memorizing, Reviewing, Seeking Social Assistance, Self-Evaluation, and Self-Consequences (Zimmerman & Pons, 1986). Pintrich and Zusho (2002) classify SRL strategies involving Planning and Goal Setting, Monitoring, Control, Reaction, and Reflection. Boekaerts and Corno (2005) and Perry et al. (2006) define SRL strategies as learning behaviors guided by metacognition (Planning, Monitoring, and Regulating Activities), strategic action (Organizing, Time Management, and Self-Evaluation), and learning motivation (Self-Confidence, Goal Setting, and Task Value).

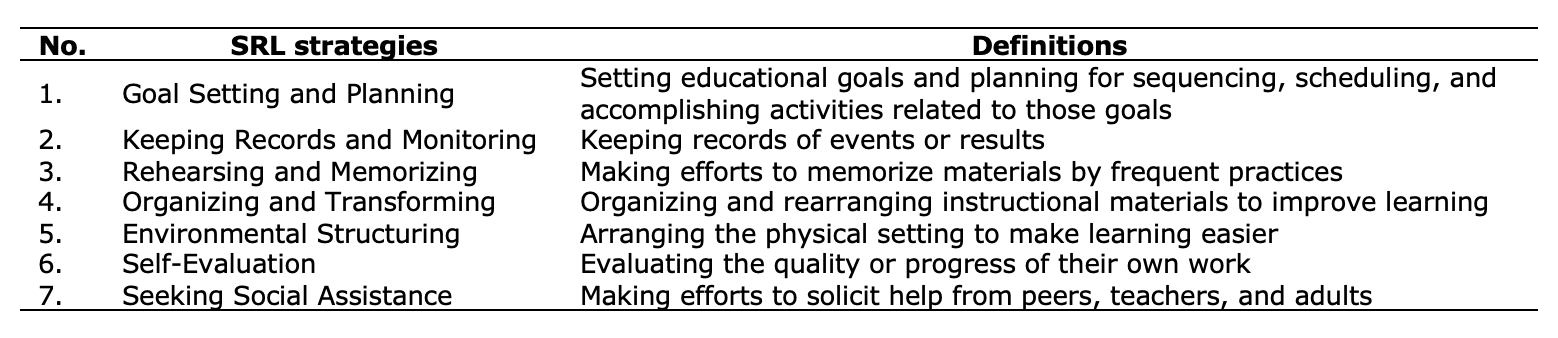

The present study focused on the exploration of seven strategies of SRL employed by Thailand EFL students with different English proficiency in CEFR levels. The strategies were Goal Setting and Planning, Keeping Records and Monitoring, Rehearsing and Memorizing, Organizing and Transforming, Environmental Structuring, Self-Evaluation,and Seeking Assistance as presented in Table 1.

Table 1. SRL strategies (Zimmerman & Pons, 1986)

Related studies of SRL strategies and English proficiency

Despite the small number, empirical studies on SRL strategies and English proficiency have been conducted in different contexts. For instance, Fukuda (2018) investigated Japanese university students’ SRL strategies and their English proficiency. The study used a questionnaire and TOEIC scores as research instruments. It was found that students’ SRL strategies could predict their English proficiency. In addition, there were significant differences between the use of SRL strategies of low– and high-proficiency students. The differences in SRL strategy use across English proficiency levels were also confirmed among Korean students (Cho & Ma, 2018). Nevertheless, different results were found by Jeon (2011) revealing that no significant differences in the use of SRL strategies between low- and high-proficiency students.

Regarding the particular use of SRL strategies, Chen et al. (2020) indicated that Goal Setting and Planning and Self-Evaluation were the strategies most used by higher scoring students. However, lower scoring students reported that they employed Keeping Records and Monitoring more frequently. In terms of the correlation between SRL strategies and English proficiency, a significant relationship was observed between Iranian EFL learners’ SRL strategies and their language proficiency (Mirhassani et al., 2007). Furthermore, Çimenli and Çoban (2019) also confirmed a significant positive correlation between Turkey students’ SRL strategies and their English proficiency levels.

Although several previous studies aimed particularly at investigating EFL learners’ SRL strategies and English proficiency, these studies did not explore the differences of SRL strategies employed by students on each level of English proficiency in the CEFR. Besides, previous studies were carried out in contexts other than the Thai one. Hu and Chen (2007) highlighted that strategy use may vary across contexts; therefore, this study set out to examine Thai EFLstudents’ use of SRL strategies with different English proficiency based on CEFR levels, and the relationship between SRL strategy use and English proficiency.

Methodology

Research design

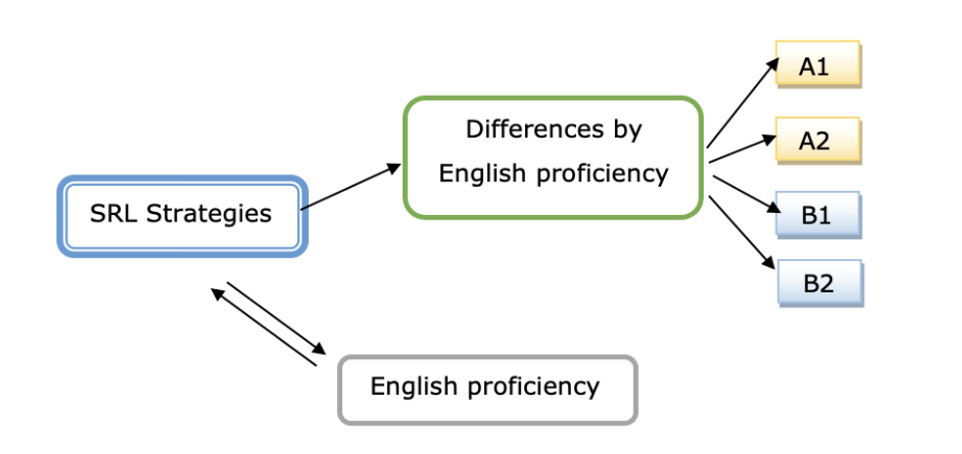

The present study employed a quantitative research design aimed at exploring students’ use of SRL strategies and their English proficiency. Quantitative research is a method of research that measures and analyzes data using statistical models and reports relationships among variables (Zedeck, 2013). Another rationale is that most of related studies used a quantitative research method. Such a rationale is considered relevant because researchers' extensive use of a certain research method to examine a single study topic suggests support of the method's acceptable applicability (Creswell, 2008). The research design is illustrated in Figure 1.

Figure 1: Research design

Participants

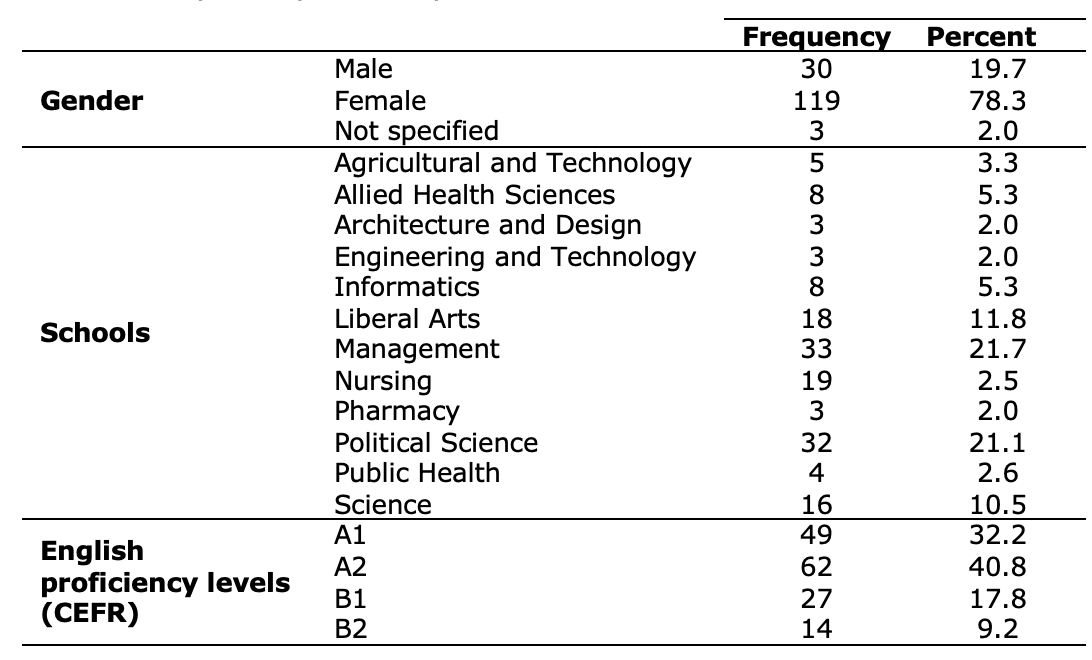

The participants in this study were second-year undergraduate non-English major students at a university in Thailand. The total number of participants was 152 students (19.7% male, 78.3% female). They were studying in twelve different schools of the university, and they were selected by purposive and random sampling methods. To begin, the purposive sampling method was used to determine the inclusion criteria that best represent the study's primary objective. The purpose of this study was to examine students' SRL strategies across a range of English proficiency levels, with a particular emphasis on second-year undergraduate non-English major students. Three criteria were developed as a result: Participants had to be: 1) second-year undergraduate students at the time of the study; 2) not majoring in English; and 3) possessing English proficiency levels A1, A2, B1, and B2. Following the purposive sampling technique, this study employed a random sampling technique. This method emphasizes that all students in the targeted population have an equal chance of being chosen as participants in this study under any circumstances. Detailed information about the participants is provided in Table 2.

Table 2. The participants’ information

Instruments

English Proficiency Test

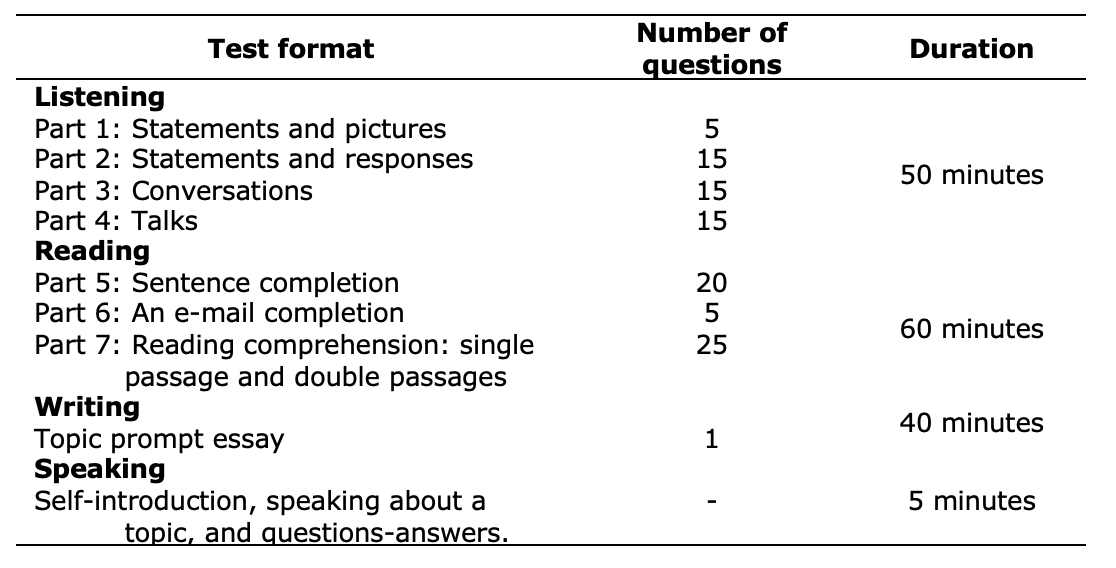

To measure students’ English proficiency, the students took an English proficiency test, the Walailak University – Test of English Proficiency (WUTEP). The test was designed by referring to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) and Classical Test Theory (CTT). It assesses listening, speaking, writing, and reading skills in the CEFR levels from A1 to C1. The test scores can be linked to other standardized tests, such as TOEFL, IELTS, and TOEIC (Waluyo, 2019). The test format can be seen in Table 3.

Table 3. The [WUTEP] format (Waluyo, 2019)

Self-Regulated Learning Strategies Questionnaire (SRLSQ)

To explore students’ SRL strategies, a survey questionnaire adapted from Wang and Bai (2017) was used. It was comprised of thirty items exploring the use of seven strategies of SRL on a five-point Likert scale: 1 (never), 2 (seldom), 3 (sometimes), 4 (often), and 5 (always). The strategies included Goal Setting and Planning (5 items), Keeping Records and Monitoring (3 items), Rehearsing and Memorizing (5 items), Organizing and Transforming (7 items), Environmental Structuring (2 items), Self-Evaluation (5 items), and Seeking Assistance (3 items). The questionnaire items were translated into Thai and the validity was checked by three native Thai speakers. In this study, the questionnaire was administered to the students after they took the English proficiency test. Prior to the questionnaire completion, their consent to participate in the study was obtained.

Data Analysis

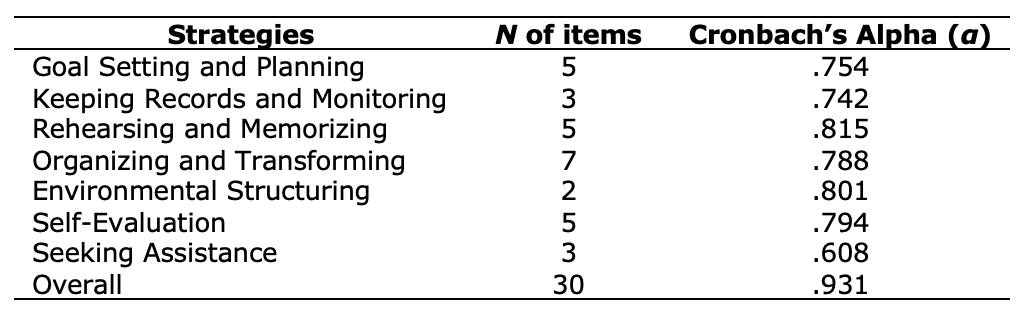

The data were analyzed by using a statistical program. First, reliability analysis was performed to check the internal consistency of the questionnaire items. The results showed acceptable and high Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients for specific and overall SRL strategies items as shown in Table 4.

Table 4. Cronbach’s Alpha coefficients

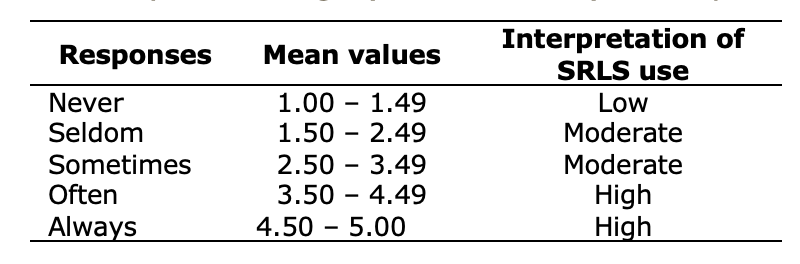

The data were then descriptively assessed for normality before being subjected to parametric testing. This study followed George and Mallery's (2003) recommendation that the values of skewness and kurtosis be less than -2 or +2 and used as a threshold of normally distributed data, and it was discovered that each of the SRL constructs had values lower than the threshold, encouraging the use of parametric tests. To explore Thai EFL students’ use of SRL strategies by English proficiency level, descriptive statistics: means and standard deviation were analyzed. The criteria for interpreting the mean values of the students’ responses to the questionnaire were identified by the ratings (Oxford, 1990), as explained in Table 5.

Table 5. Interpretation of the mean values

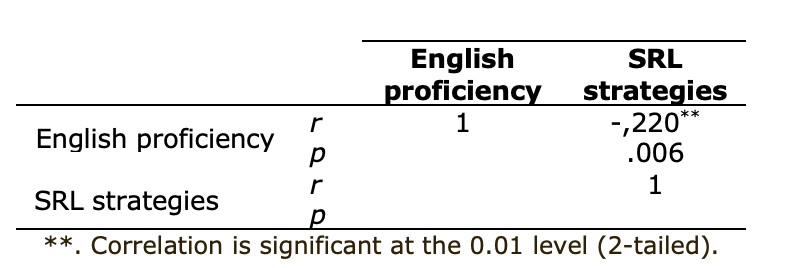

Moreover, to further examine of the differences in the use of SRL strategies across English proficiency levels, the data were also analyzed by using One-Way ANOVA. Lastly, a Pearson correlation was carried out to investigate the relationship between SRL strategies and students’ English proficiency.

Results

Thai EFL students’ use of SRL strategies by English proficiency level

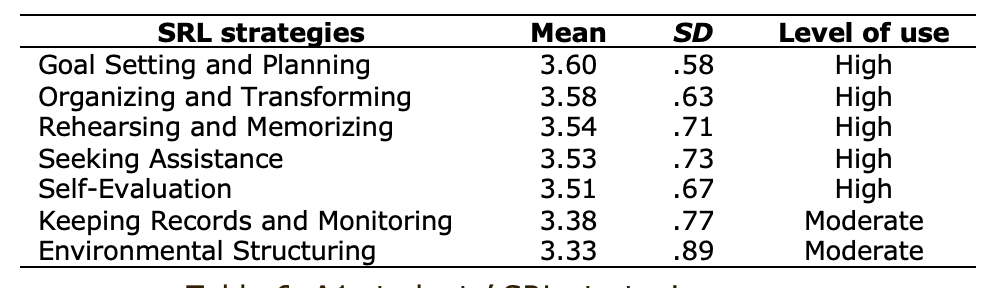

Descriptive statistics (see Table 6) showed that the most-used strategy by A1 students was Goal Setting and Planning(M = 3.60; SD = .58). Other strategies with high-frequency use were Organizing and Transforming (M = 3.58; SD = .63), Rehearsing and Memorizing (M = 3.54; SD = .71), Seeking Assistance (M = 3.53; SD = .73), and Self-Evaluation(M = 3.51; SD = .67). However, students also reported that they employed Keeping Records and Monitoring (M = 3.38; SD = .77) and Environmental Structuring (M = 3.33; SD = .89) moderately.

Table 6. A1 students’ SRL strategies

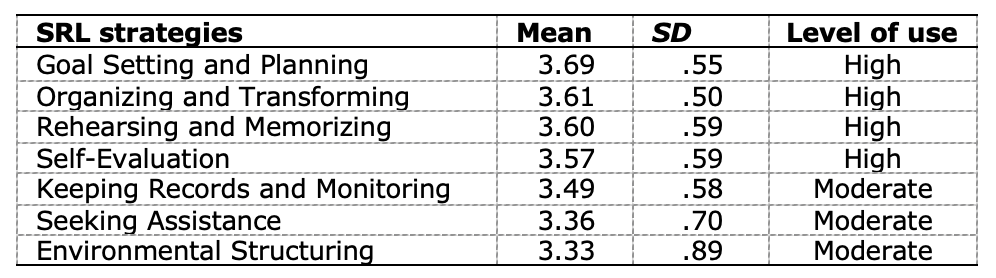

For A2 students, descriptive statistics (see Table 7) also revealed Goal Setting and Planning as the most-used strategy (M = 3.69; SD = .55). It was followed by other high frequency used strategies including Organizing and Transforming(M = 3.61; SD = .50), Rehearsing and Memorizing (M = 3.60; SD = .59), and Seeking Evaluation (M = 3.57; SD = .59). Unlike A1 students, they reported a moderate use of Seeking Assistance (M = 3.36; SD = .70). Keeping Records and Monitoring (M = 3.49; SD = .58) and Environmental Structuring (M = 3.32; SD = .84) were also reported as moderate-used strategies by A2 students.

Table 7. A2 students’ SRL strategies

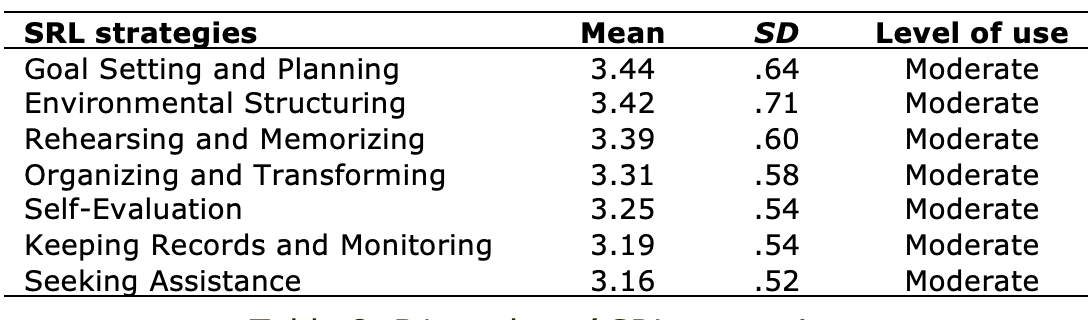

Interestingly, as shown in Table 8, B1 students reported that they used all strategies of SRL moderately. Goal Setting and Planning (M = 3.44; SD = .64) was reported as the most-used strategy, followed by Environmental Structuring (M = 3.42; SD = .71), Rehearsing and Memorizing (M = 3.39; SD = .60), Organizing and Transforming (M = 3.31; SD = .58), Self-Evaluation (M = 3.25; SD = .54), Keeping Records and Monitoring (M = 3.19; SD = .53), and Seeking Assistance (M = 3.16; SD = .52).

Table 8. B1 students’ SRL strategies

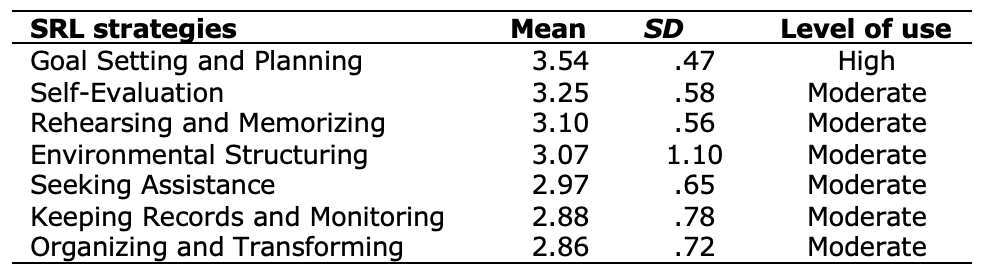

Like students at A1, A2, and B1 levels, B2 students also reported Goal Setting and Planning (M = 3.54; SD = .47) as the most-used strategy, as depicted in Table 9. However, they reported moderate use of all other SRL strategies: Self-Evaluation (M = 3.25; SD = .58), Rehearsing and Memorizing (M = 3.10; SD = .56), Environmental Structuring (M = 3.07; SD = 1.10), Seeking Assistance (M = 2.97; SD = .65), Keeping Records and Monitoring (M = 2.88; SD = .78), and Organizing and Transforming (M = 2.86; SD = .72).

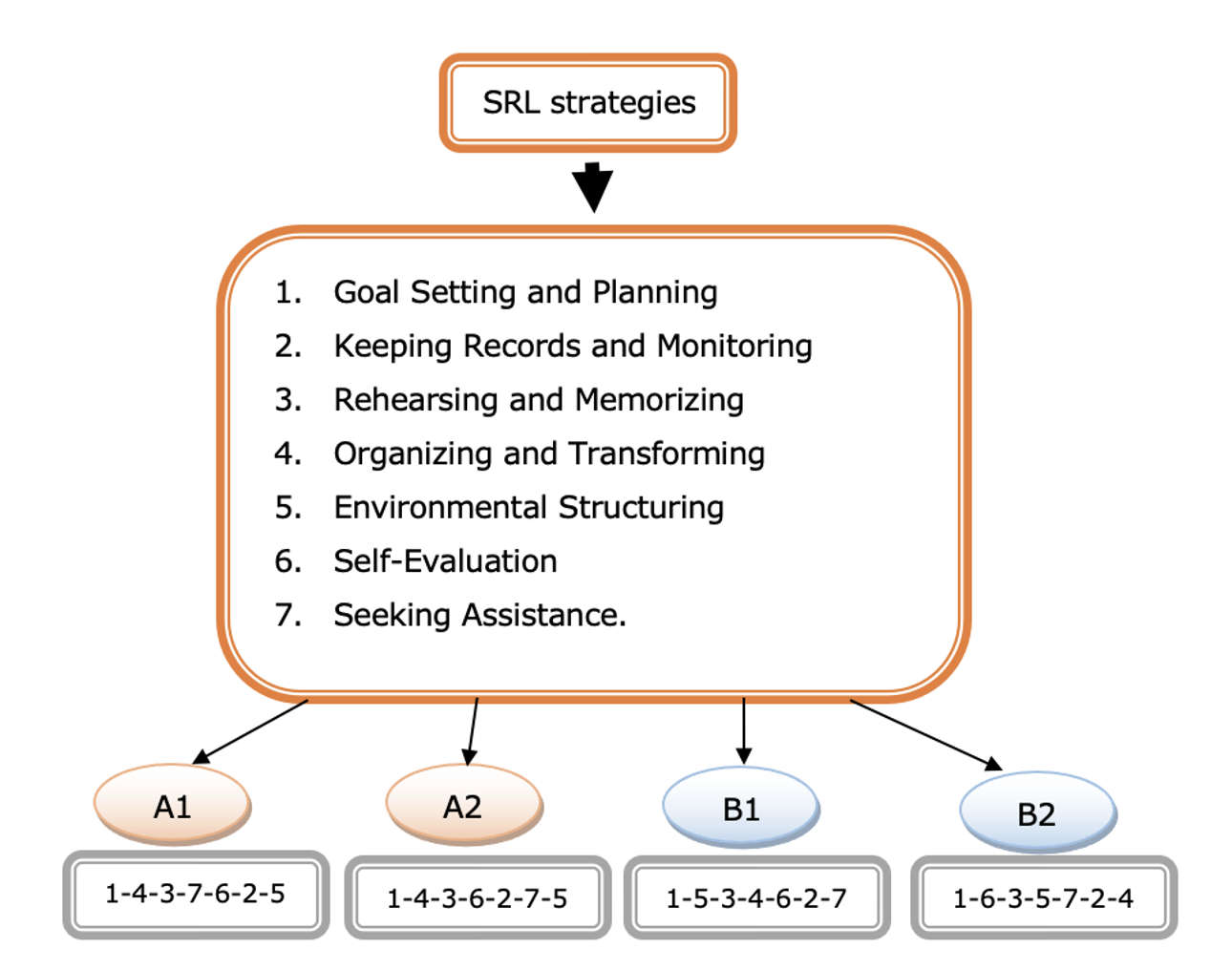

To sum up, the patterns of SRL strategies on each level of English proficiency are described in Figure 2.

Figure 2. The patterns of SRL strategies on each English proficiency levels

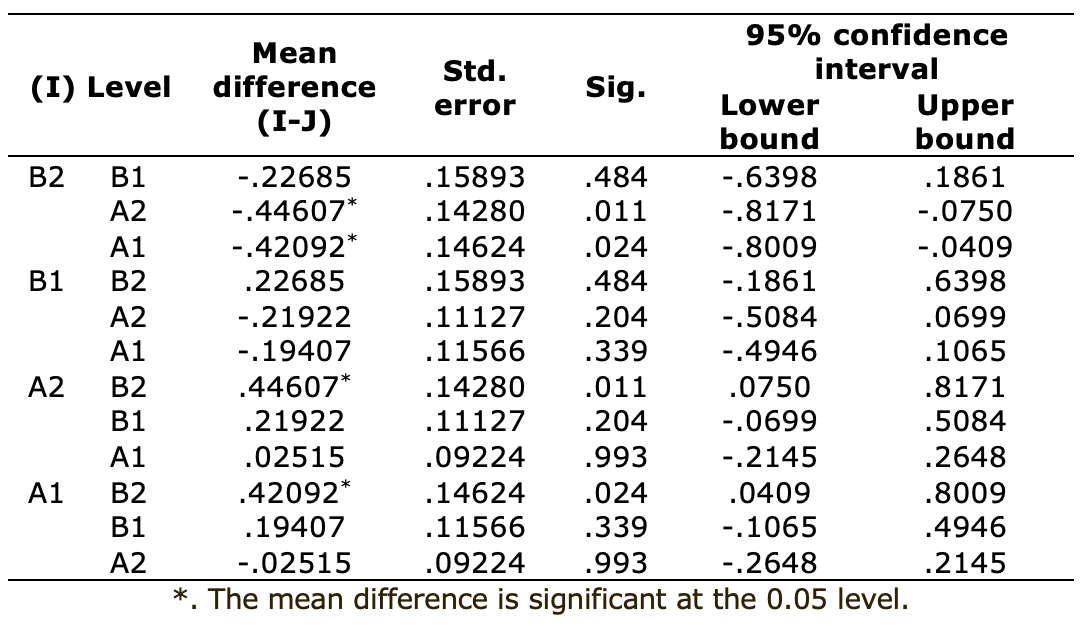

The results of a One-Way ANOVA (see Table 10) revealed that there was little significant difference in the use of SRL strategies between the A1 and A2 groups (p = .993). Furthermore, little significant difference was observed between the B1 group and the groups at A1 (p = .339), A2 (p = .204), and B2 (p = .484) levels of English proficiency. However, the results showed a statistically significant difference in the use of SRL strategies between the group at A1 and B2 levels (p = .024), as well as between A2 and B2 students (p = .011).

Table 10. The results of One-Way ANOVA (N = 152)

Relationship between SRL Strategies and English proficiency

Pearson correlation analysis showed that there was a significant negative relationship between students’ SRL strategies and their English proficiency (r = -.200, p = .006), as presented in Table 11.

Table 11. The results of Pearson correlation (N = 152)

Discussion

The main objectives of the present study were to investigate SRL strategies employed by Thai EFL students with different English proficiency levels in CEFR and to examine the relationship between their SRL strategies and English proficiency. This study observed differences in the frequency of SRL strategies used by Thai EFL students with different English proficiency levels. The statistical results showed that students at A1 and A2 levels, as basic users of English, employed a greater variety of SRL strategies than B1 and B2 students groups as independent users of English according to CEFR. A1 and A2 students reported high use of Goal Setting and Planning, Organizing and Transforming, Rehearsing and Memorizing, and Self-Evaluation. However, B1 students reported that they employed all strategies of SRL moderately. Students at B2 level, also reported moderate use of SRL strategies, except for Goal Setting and Planning. Students might adopt a range of frequent usage of SRL strategies because they were aware of their flaws and strengths (Apridayani & Teo, 2021; Chen et al., 2020).

Despite the fact that varied frequencies of SRL strategies were seen across English proficiency levels, this study found that Goal Setting and Planning was the most commonly employed by students at all four English proficiency levels: A1, A2, B1, and B2. This result is not in line with the findings of the aforementioned studies by Chen et al. (2020) and Pratotep and Chinwono (2008) suggesting that only high-proficiency students employed Goal Setting and Planning frequently. In this study, the finding revealed that, despite having a diverse range of English proficiency, the Thai EFL students understood the significance of Goal Setting and Planning in their English learning process. Zimmerman and Pons (1986) describe Goal Setting and Planning as the strategy that students use to set their educational goals, then plan the sequences of the accomplishment of those goals

The next finding revealed no significant difference in SRL strategies use between A1 and A2 students. It indicated that Thai EFL students at basic English levels seemed to employ similar SRL strategies in their English learning. However, the present study showed significant differences in the use of SRL strategies between the basic (A1 and A2) groups and the B2 group. These results sustain the findings of previous studies (Cho & Ma, 2018; Fukuda, 2018) indicating that there were significant differences between the use of SRL strategies among low– and high-proficiency students. In this study, B2 students as the highest English proficiency level might use only particular strategies in their English learning due to their awareness of English proficiency. This study observed little significant differences between the B1 group and the groups at A1, A2, and B2 levels in the use of SRL strategies. It was noted that this group of students seemed to use each strategy of SRL including Goal Setting and Planning, Keeping Records and Monitoring, Rehearsing and Memorizing, Organizing and Transforming, Environmental Structuring, Self-Evaluation, and Seeking Assistance equally to maintain or develop their English proficiency levels.

The last finding revealed a significant negative relationship between students’ SRL strategies and their English proficiency. This suggests that students at low-proficiency levels reported high use of SRL strategies. This finding does not lend support to previous studies (Çimenli & Çoban, 2019; Mirhassani et al., 2007). The present study indicated that Thai EFL students at A1 and A2 levels might be aware of their weaknesses and motivated to use more SRL strategies to improve their English proficiency levels.

Conclusion

Based on the findings reported in the previous sections, there are two major conclusions of this study. Firstly, students at A1 and A2 of English proficiency levels had higher use of SRL strategies in their English learning than B1 and B2 students. However, this study indicated Goal Setting and Planning as the strategy most used by four groups of students. In addition, no significant difference was observed in the use of SRL strategies between A1 and A2 students. This lack of significant difference was also found between the B1 group and A1, A2, and B2 groups. However, this study revealed significant differences in the use of SRL strategies between B2 students and the A1/A2 groups.

The first findings indicate that Thai EFL students’ awareness of their English proficiency levels might encourage them to choose or decide on SRL strategies they employed. Therefore, they had their own patterns in the use of SRL strategies. As shown in Table 7, A1 students had five most-used SRL strategies including Goal Setting and Planning, Organizing and Transforming, Rehearsing and Memorizing, Seeking Assistance, and Self-Evaluation. In addition, except Seeking Assistance, A2 students also reported the same most-used strategies as A1 students, as depicted in Table 8. However, B1 students reported that they employed each strategy of SRL moderately as presented in Table 9. Furthermore, B2 students believed that they used SRL strategies sparingly, with the exception of Goal Setting and Planning.

Secondly, little significant negative relation was found between SRL strategies and English proficiency. In this study, students who reported high use of SRL strategies were students at A1 and A2 levels. This study relied on a self-report questionnaire, which can provide information about SRL strategies but does not guarantee that they would be employed effectively. According to Wang et al. (2012), English classroom instructions can influence students' adoption of SRL strategies. Therefore, this study suggests that English teachers should incorporate SRL strategy practice in their classrooms and assist students in developing their own understanding and use of SRL strategies. Lee (2002) has shown that SRL strategies can be integrated into classroom instruction.

Although this study was meticulously planned, it has limitations. This study was limited to the investigation of EFLstudents’ self-regulated learning (SRL) strategies at one university in Thailand. The results of this study may or may not be applicable to EFL learners in other contexts. The next limitation is related to the number of participants. Different results might have been generated if there were greater number of students for each English proficiency level. Finally, this study acknowledges that the inclusion of qualitative data, such as individual interviews and focus-group discussions with students, could have assisted the researcher in delving deeper into students' personal experiences with their use of SRL strategies and the connection to their English proficiency development.

This study revealed that Thai EFL students in this university appeared to be aware of how to self-regulate their own English learning in alignment with their proficiency levels. Nonetheless, in order to change such perceptions into long-term academic behaviors, ongoing guidance is essential. Thus, further inquiry into how the English curriculum and course instructions have dealt with non-cognitive skill development among Thai students is proposed by the current study. Specifically, it is also recommended that future studies investigate the effectiveness of students’ use of SRL strategies.

References

Apridayani, A., & Teo, A. (2021). The interplay among SRL strategies, English self-efficacy, and English proficiency of Thai university students. Studies in English Language and Education, 8(3). https://doi.org/10.24815/siele.v8i3.20213

Bai, R., Hu, G., & Gu, P. Y. (2014). The relationship between use of writing strategies and English proficiency in Singapore primary schools. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 23(3), 355-365. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-013-0110-0

Bjork, R. A., Dunlosky, J., & Kornell, N. (2013). Self-regulated learning: Beliefs, techniques, and illusions. Annual Review of Psychology, 64, 417-444. https://doi.org/10.1146/annurev-psych-113011-143823

Boekaerts, M. (1997). Self-regulated learning: A new concept embraced by researchers, policy makers, educators, teachers, and students. Learning and Instruction, 7(2), 161-186. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0959-4752(96)00015-1

Boekaerts, M., & Corno, L. (2005). Self‐regulation in the classroom: A perspective on assessment and intervention. Applied Psychology, 54(2), 199-231. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1464-0597.2005.00205.x

Canale, M. (1983). On some dimensions of language proficiency. In J. W. Oller (Ed.). Issues in language testing research. Newbury House.

Chen, X., Wang, C., & Kim, D.-H. (2020). Self‐regulated learning strategy profiles among English as a foreign language learner. TESOL Quarterly, 54(1), 234-251. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.540

Cho, Y. A., & Ma, J. H. (2018). Self-regulated learning and English proficiency of Korean EFL college students. English Literature Studies, 44(1), 219-241. http://doi.org/10.21559/aellk.2018.44.1.011

Çimenli, B., & Çoban, M. H. (2019). Self-efficacy beliefs and self-regulated learning strategies of prep school students and their relation with language proficiency levels. Bartın Üniversitesi Eğitim Fakültesi Dergis, 8(3), 1072-1087. https://dergipark.org.tr/en/pub/buefad/issue/49482/603454

Council of Europe. (2001). A Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. Cambridge University Press.

Creswell, J.W. (2008). Educational research: Planning, conducting, and evaluating quantitative and qualitative research. Pearson.

Education First (EF). (2020). EF EPI 2020 – EF English Proficiency Index – Thailand. Retrieved 9 January, 2022 from https://www.ef.co.th/epi/regions/asia/thailand

Fukuda, A. (2018). The Japanese EFL learners' self-regulated language learning and proficiency. Journal of Pan-Pacific Association of Applied Linguistics, 22(1), 65-87.

George, D., & Mallery, P. (2003). SPSS for Windows step by step: A simple guide and reference 11.0 update (4th ed.). Allyn & Bacon

Harsch, C. (2017). Proficiency. ELT Journal, 71(2), 250-253. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccw067

Hu, G. W., & Chen, B. (2007). A protocol-based study of university level Chinese EFL learners’ writing strategies. English Australia Journal, 23(2), 37-56.

Jeon, J. (2011). The effect of self-regulated learning ability components on English performance. Journal of Language Sciences, 18(4), 145-168.

Ketamon, T., Promduang, P., Phayap, N., & Chanchayanon, A. (2018). The implementation of CEFR in the Thai education system. Hatyai Academic Journal, 16(1), 77-88. https://so01.tci-thaijo.org/index.php/HatyaiAcademicJournal/article/view/130142/97729

Kyllonen, P. C. (2012). The importance of higher education and the role of noncognitive attributes in college success. Pensamiento Educativo, 49(2), 84–100. http://pensamientoeducativo.uc.cl/index.php/pel/article/view/25831/20743

Lee, C. (2002). Strategy and self-regulation instruction as contributors to improving students' cognitive model in an ESL program. English for Specific Purposes, 21(3), 261–289. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0889-4906(01)00008-4

Ministry of Education. (2014). The guidelines on English language teaching and learning reforming policy. http://www.en.moe.go.th

Mirhassani, A., Akbari, R., Dehghan, M., Noordin, N., & Abdullah, M. (2007). The relationship between Iranian EFL learners’ goal-oriented and self-regulated learning and their language proficiency. Journal of Teaching English Language and Literature Society of Iran (TELLSI), 1(2), 1-15. http://www.teljournal.org/article_113136_e2aae55b59d385210ee864814c0143e5.pdf

Nakata, Y. (2010). Toward a framework for self-regulated language-learning. TESL Canada Journal, 27(2), 1-10. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v27i2.1047

Ortmeier-Hooper, C., & Ruecker, T. (Eds.). (2016). Linguistically diverse immigrant and resident writers: Transitions from high school to college. Routledge.

Oxford., R. L. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. Heinle & Heinle.

Richardson, M., Abraham, C., & Bond, R. (2012). Psychological correlates of university students' academic performance: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 138(2), 353. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/a0026838

Rosen, J. A., Glennie, E. J., Dalton, B. W., Lennon, J. M., & Bozick, R. N. (2010). Noncognitive skills in the classroom: New perspectives on educational research. RTI Press Publication.

Perry, N. E., Phillips, L., & Hutchinson, L. R. (2006). Mentoring student teachers to support for self-regulated learning. Elementary School Journal, 106(3), 237-254. https://www.journals.uchicago.edu/doi/pdf/10.1086/501485

Pintrich, P. R., & Zusho, A. (2002). The development of academic self-regulation: The role of cognitive and motivational factors. In A. Wigfield & J. S. Eccle (Eds.), Development of achievement motivation (pp. 249-284). Elsevier.

Pratontep, C., & Chinwonno, A. (2008). Self-regulated learning by Thai university students in an EFL extensive reading program. MANUSYA: Journal of Humanities, 11(2), 104-124. http://www.manusya.journals.chula.ac.th/wp-content/uploads/2021/06/36-104-124.pdf

Samruayruen, B., Enriquez, J., Natakuatoong, O., & Samruayruen, K. (2013). Self-regulated learning: A key of a successful learner in online learning environments in Thailand. Journal of Educational Computing Research, 48(1), 45-69. https://doi.org/10.2190%2FEC.48.1.c

Seker, M. (2016). The use of self-regulation strategies by foreign language learners and its role in language achievement. Language Teaching Research, 20(5), 600-618. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1362168815578550

Waluyo, B. (2019). Examining Thai first-year university students’ English proficiency on CEFR levels. The New English Teacher, 13(2), 51-71. http://www.assumptionjournal.au.edu/index.php/newEnglishTeacher/article/view/3651/2368

Wang, C., & Bai, B. (2017). Validating the instruments to measure ESL/EFL learners' self‐efficacy beliefs and self‐regulated learning strategies. TESOL Quarterly, 51(4), 931-947. https://doi.org/10.1002/tesq.355

Wang, C., Hu, J., Zhang, G., Chang, Y., & Xu, Y. (2012). Chinese college students’ self-regulated learning strategies and self-efficacy beliefs in learning English as a foreign language. Journal of Research in Education, 22(2), 103-135.

Woottipong, K. (2019). Effects of self-regulated learning strategy training in an online learning environment on university students’ learning achievement and their reported use of strategies. Proceedings of RSU International Research Conference, Thailand, 752-758.https://doi.org/ 10.14458/RSU.res.2019.73

Zedeck, S. (Ed), (2013). APA dictionary of statistics and research methods. American Psychological Association.

Zimmerman, B. J. (1990). Self-regulated learning and academic achievement: An overview. Educational Psychologist, 25(1), 3-17. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep2501_2

Zimmerman, B. J. (2002). Becoming a self-regulated learner: An overview. Theory into Practice, 41(2), 64-70.https://doi.org/10.1207/s15430421tip4102_2

Zimmerman, B. J., & Pons, M. M. (1986). Development of a structured interview for assessing student use of self-regulated learning strategies. American Educational Research Journal, 23(4), 614-628. https://doi.org/10.3102%2F00028312023004614