Introduction

Before planning instruction, it is necessary to understand the knowledge, skills, capacities, and experiences that students have obtained through their previous schooling and socialization (Herrera, Cabral, & Murry, 2013). Therefore, students should be pre-assessed in four important areas: cognitive, academic, sociocultural, and linguistic. To achieve this goal, it is possible to use formal and informal pre-assessments. It is true that standardized tests (formal pre-assessments) can be used at the beginning of each year or semester, especially since it is a requirement in many educational institutions in different countries around the world, including Ecuador and the United States. However, one should not rely solely on the results of these tests because they often cause higher levels of anxiety, elevate the students’ affective filter, and sometimes provide an inaccurate representation of students' knowledge and skills (Gass, Behney, & Plonsky, 2013; Krashen & Bland, 2014). Therefore, informal assessments such as class observations, parent interviews, student questionnaires, and classroom discussions, among others, can be implemented to collect information about students' prior knowledge, skills, learning styles, and sociocultural backgrounds. Throughout this article, all these forms of pre-assessment tools, as well as their use and benefits for learning English as a foreign language, will be explained. Nevertheless, special attention will be given to two non-traditional tools: Biography Cards and Linking Language.

Literature Review

Pre-Instructional Assessment Tools

Student Biography Cards

One of the instruments that can be used to pre-assess students is the so-called Student Biography Card (Herrera et al., 2013). This instrument gathers information about students’ age, region or city of birth, previous academic experiences, prior schooling (private or public school), first language (L1) / second language (L2) levels of proficiency in listening, speaking, reading, and writing, and preferred grouping configuration (individual, pairs, groups, or entire class).

Since students are the most important elements of the classroom, it is essential to get to know them in depth. Identifying their prior experiences, schooling, and learning is crucial to implement classroom adaptations and instructional accommodations necessary for ensuring student success (Herrera, 2015; Homel & Ryan, 2014). Each student brings a story to the classroom, and teachers should make an effort to explore it. Thus, biography cards help teachers to collect valuable data on four important dimensions: sociocultural, cognitive, academic, and linguistic (Kucer, 2014; Thomas & Collier, 2012).

This biography card also gathers data like students’ stages of second language acquisition and previous exposure to first and second language. This information is especially important because, as Herrera and Murry (2016) show, the more literate and schooled a student is in his or her first language, the easier it will be for that learner to transfer skills and concepts from L1 to L2. Besides, it is essential to provide students consistent and structured accommodations according to their linguistic levels. As Krashen & Bland (2014) explain, there are five stages of second language acquisition: Preproduction, Early Production, Speech Emergence, Intermediate Fluency, and Advanced Fluency, and each stage has its own characteristics. Therefore, it is necessary to adapt the classes to the stage of each student. For instance, in the Preproduction stage, students rely more heavily on picture clues and respond non-verbally by pointing, gesturing, or drawing. Thus, in this stage, it is necessary to use many visuals, gestures, and physical movements; make connections with their previous language, knowledge, and experiences; pair them with more proficient peers; and allow them to go through a silent period (Berg, Petrón, & Greybeck, 2012; Herrera, Pérez, & Escamilla,2014). However, as they move to the next stages, their language proficiency increases; therefore, the complexity of the activities will also increase. At the beginning, students will have to remember and understand information, but as they move forward in their language level, they will have to apply, analyze, and evaluate what they are learning (Bloom, 1984; Faruk, Guzel, Koroglu, & Ilhan, 2012). Finally, once the students get to the Advanced Fluency stage, it will be necessary to maximize the students’ reading, writing, listening, and speaking skills by exposing them to more complex content-based activities.

Student Questionnaires

Another instrument that can be used is the student questionnaire because it provides information about the learners’ preferred intelligences such as linguistic, musical, logical-mathematical, naturalistic, spatial, intrapersonal, interpersonal, and bodily-kinesthetic (Gardner, 1983, 2011). Besides, it contributes to identify how each student processes information. For example, some students are left-brain dominant and need to be exposed to sequential instruction, while others are right-brain dominant and prefer intuitive thinking (Burden, 2013; Ghraibeh, 2012). In addition, when working in cooperation with the Student Counseling Department, it is possible to have access to available school records related to enrollment, attendance, and achievement from previous academic years. That information can also be helpful to adapt and modify the lessons according to the needs of students.

Once all this information has been collected, the next step is to involve parents in the process of education of their children. According to Herrera at al. (2013), partnerships between schools, families, and communities are essential in creating successful students. Although these partnerships present diverse challenges, the benefits recompense the efforts. Therefore, if the objective is to know the students in depth, educators need to conduct parent interviews at school.

Parent Conferences and Interviews

It is important to acquire knowledge about students by talking to parents or family members. Although home visits such as those implemented in United States are not common in Ecuador, here it is possible to conduct in-campus parent interviews at schools. During these conferences, teachers can interview parents on topics such as family structure, languages spoken at home, and students’ exposure to literacy activities at home. It is also possible to obtain information about students’ prior academic experiences in order to identify how they learned English in previous years (grammar-based approach or communicative approach).

In addition, it is vital to know if the family has moved from one city or region to another or if the student has been transferred from another educational institution. When students find themselves immersed in a new culture, they can feel frustration, anxiety, depression or anger because their normal ways of thinking and interacting suddenly become strange to people in the new culture (Herrera at al., 2013; Igoa, 2013). Therefore, educators need to be prepared to recognize and respond appropriately to students’ actions that demonstrate “disengagement from or rebellion against the new culture” (Herrera et al., 2013, p. 43). Besides, professors have to develop effective interventions and class activities in the classroom to prevent cultural shock or to support students when they face difficulties with acculturation.

At the end of the interview, it can also be a good idea to ask questions such as: What do you think your child does particularly well? What do you want me to know about him or her? Do you have any concerns? What would you like to see your child accomplish this period, semester, or year? (Herrera et al., 2013). In that way, educators will not only get more information about students, but also engage and motivate parents at the same time.

Linking Language

To implement this strategy, teachers use pictures from the specific content being taught to activate students’ existing knowledge and vocabulary prior to instruction. The pictures are used as a bridge between the content and the students’ background knowledge (Herrera, Kavimandan, & Holmes,2012). This strategy can be implemented with the whole class, in small groups, pairs, or individuals.

Application

This study was conducted with a group of ESL students in a public elementary school of United States. All of them were part of an ESL Pull-Out program since they had some challenges with their performance at school and with either their academic or their conversational English. They all were around nine to ten years old and were in 4th grade. Nevertheless, there was a lot of valuable information about the students that was unknown; such as information about their sociocultural, linguistic, academic and cognitive background that could contribute to understand the challenges students were facing and to plan and adapt instruction to their needs. This situation showed the necessity of incorporating diverse pre-assessment tools at the beginning of the school year and at the beginning of each lesson, in order to develop an informed planning of the teaching-learning process.

There are several pre-assessment tools that can be used. Most studies focus on student questionnaires, parent conferences, and parent or student interviews. However, there are other useful tools that allow to obtain vital information about the students’ background and that have not been widely researched. This study focuses on two of them: Student Biography Cards and Linking Language. Throughout this paper, it will be possible to observe the type of information that can be obtained through these informal pre-assessment tools, as well as the benefits that this data provides to accommodate and better support ESL/EFL students coming from diverse sociocultural, linguistic, academic, and cognitive backgrounds.

Student Biography Cards

How was the tool implemented?

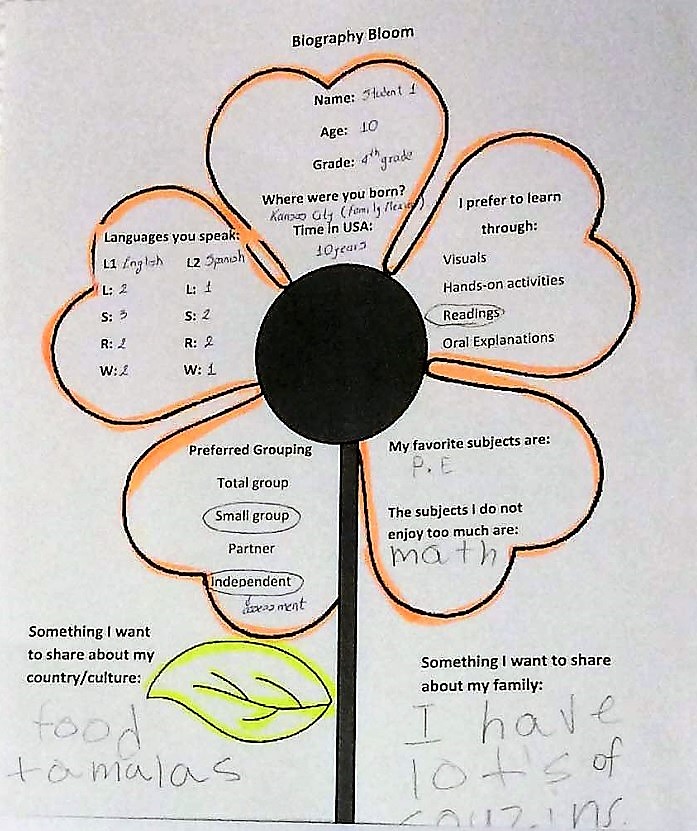

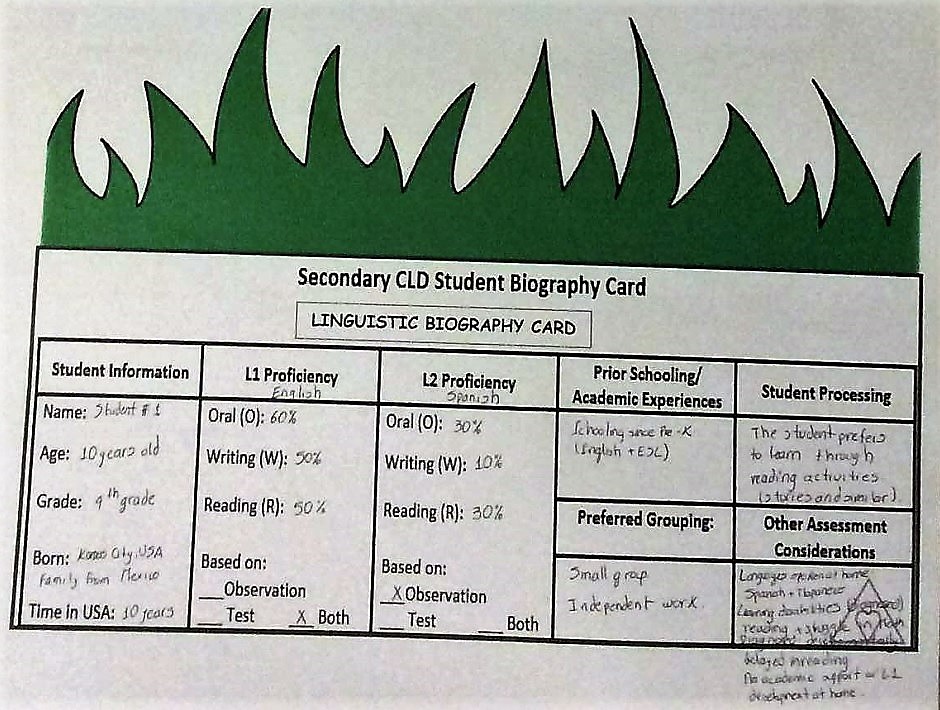

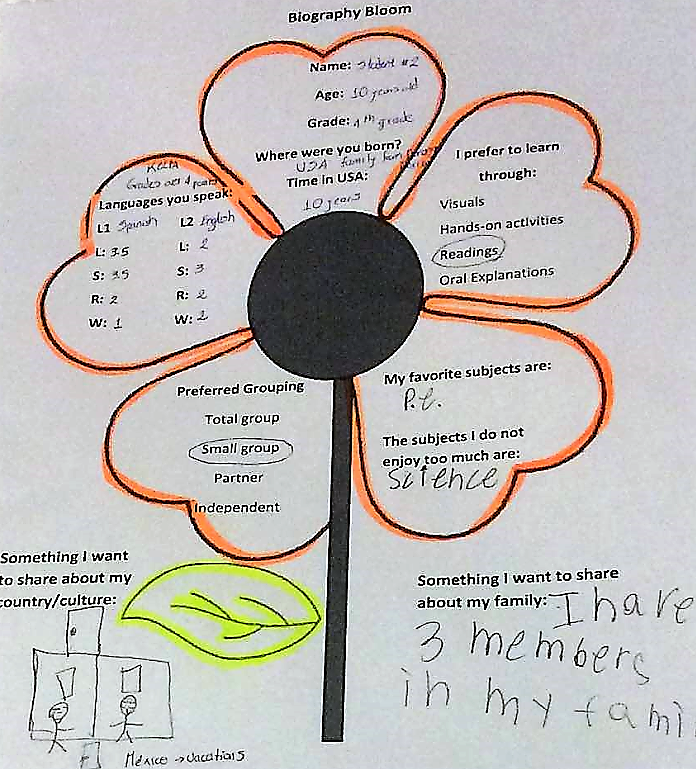

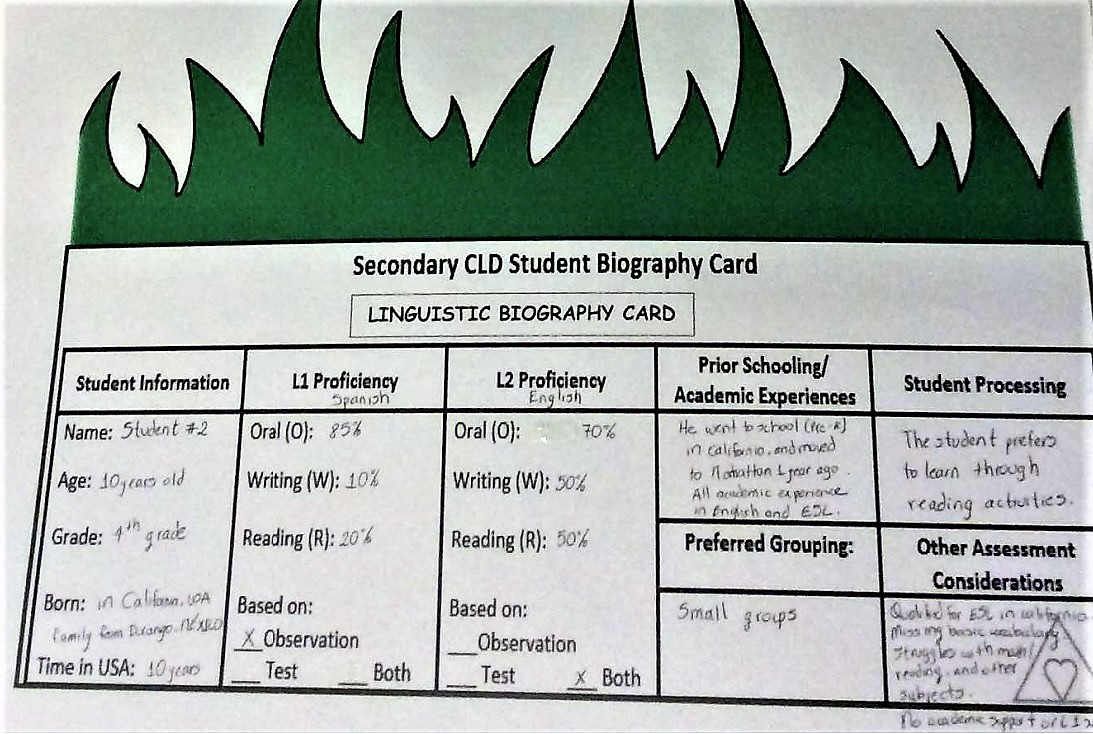

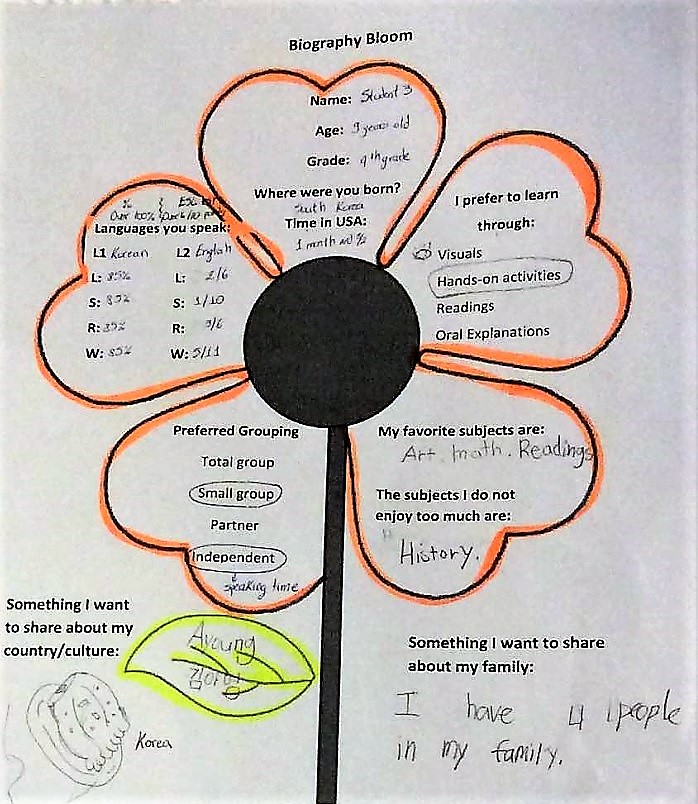

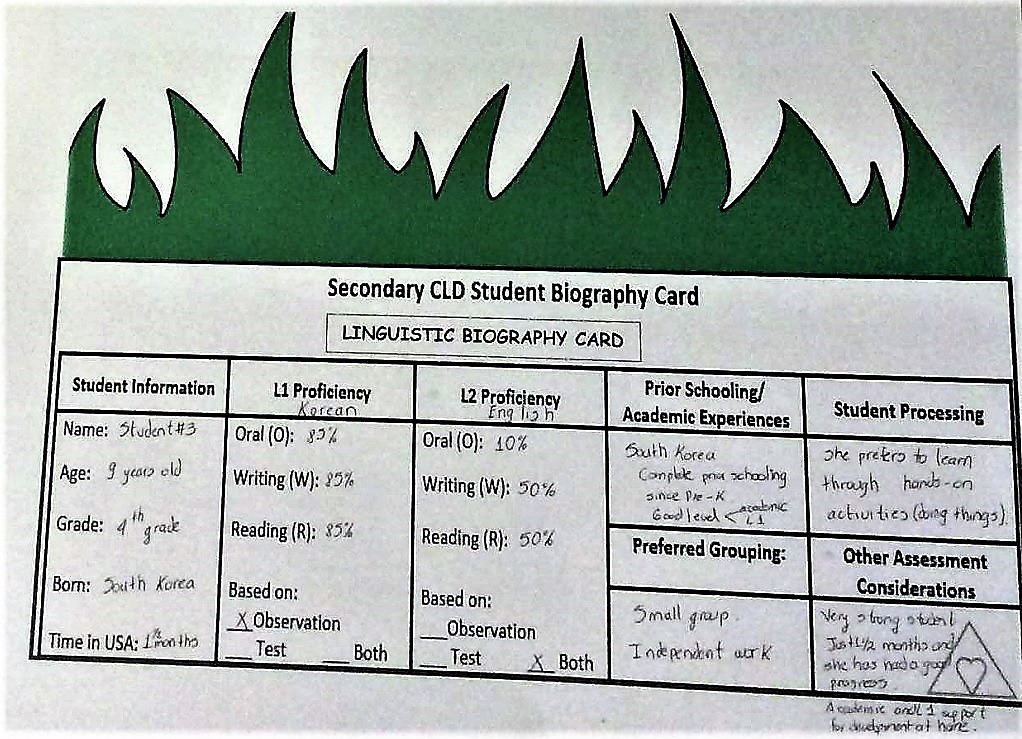

At the beginning of the school year, information about students’ linguistic, cognitive, sociocultural and academic background was collected through Biography Cards and Biography Blooms (a biograph card in the form of a flower) as seen in Figures 1-6. The Biography Blooms were first filled out by the students with information about family and cultural background as well as country of origin, time in United States, favorite subjects, preferred grouping, and information processing (preferred way of learning). The rest of the data such as language proficiency, prior schooling, prior academic experiences, and other assessment considerations like learning disabilities, parental academic support, and academic struggles was provided by the ESL Principal Teacher who knew the students and their parents in depth. Due to the fact that this teacher had worked with them ever since they enrolled in that school, the information she provided was vital to offer students the accommodations, scaffolding, and support they needed.

Figure 1. Biography Bloom: Student #1

Figure 2. Biography Card: Student #1

Figure 3. Biography Bloom: Student #2

Figure 4. Biography Card: Student #2

Figure 5. Biography Bloom: Student #3

Figure 6. Biography Card: Student #3

What results were obtained?

Through the Biography Cards, it was possible to discover that most students in the class preferred to work individually and in small groups, and that they liked to learn through readings and hand-on activities. In addition, the information collected revealed the following results: a) one student was diagnosed with learning disabilities; b) one student struggled not only with language development, but also with academic achievement in Mathematics and Science; c) one student had problems with oral communication since he was a newcomer; d) most students were in the Early Production and Speech Emergence stages of second language acquisition; e) most students did not have academic support at home.

With these results, it was possible to determine that it was necessary to make modifications and adaptations to the class based on the needs the students had. For example, teachers had to connect the content of the lesson to the cultural background of students, use a lot of visuals and hands-on activities, provide L1 support during class instruction, use guarded vocabulary (list of terms that may cause problems for students) during instruction, and implement instructional activities that would promote the development of all four language skills.

Being familiar with the cognitive and sociocultural history of students was also essential to succeed. By implementing these Biography Cards, it was possible to obtain information about the learners’ funds of knowledge (family), prior knowledge (community), and academic knowledge (school); as well as information about their interests and needs regarding language and academic instruction, and adapt instruction to fulfill those needs. Unfortunately, many teachers who have ESL/EFL learners in their classrooms focus only on the linguistic dimension. They usually think that if students learn the target language, everything else in their school performance will fall into place (Herrera, 2015). However, the sociocultural aspect is important too because high literacy goals are best achieved when students are immersed in meaningful learning contexts (Dalton, 1998; Tedick, 2012).

Linking Language

Pre-assessment should occur not only at the beginning of the school year, but also at the beginning of every lesson as instructors begin to introduce new topics. For that purpose, different pre-assessment tools, like Linking Language, can be used.

How was the tool implemented?

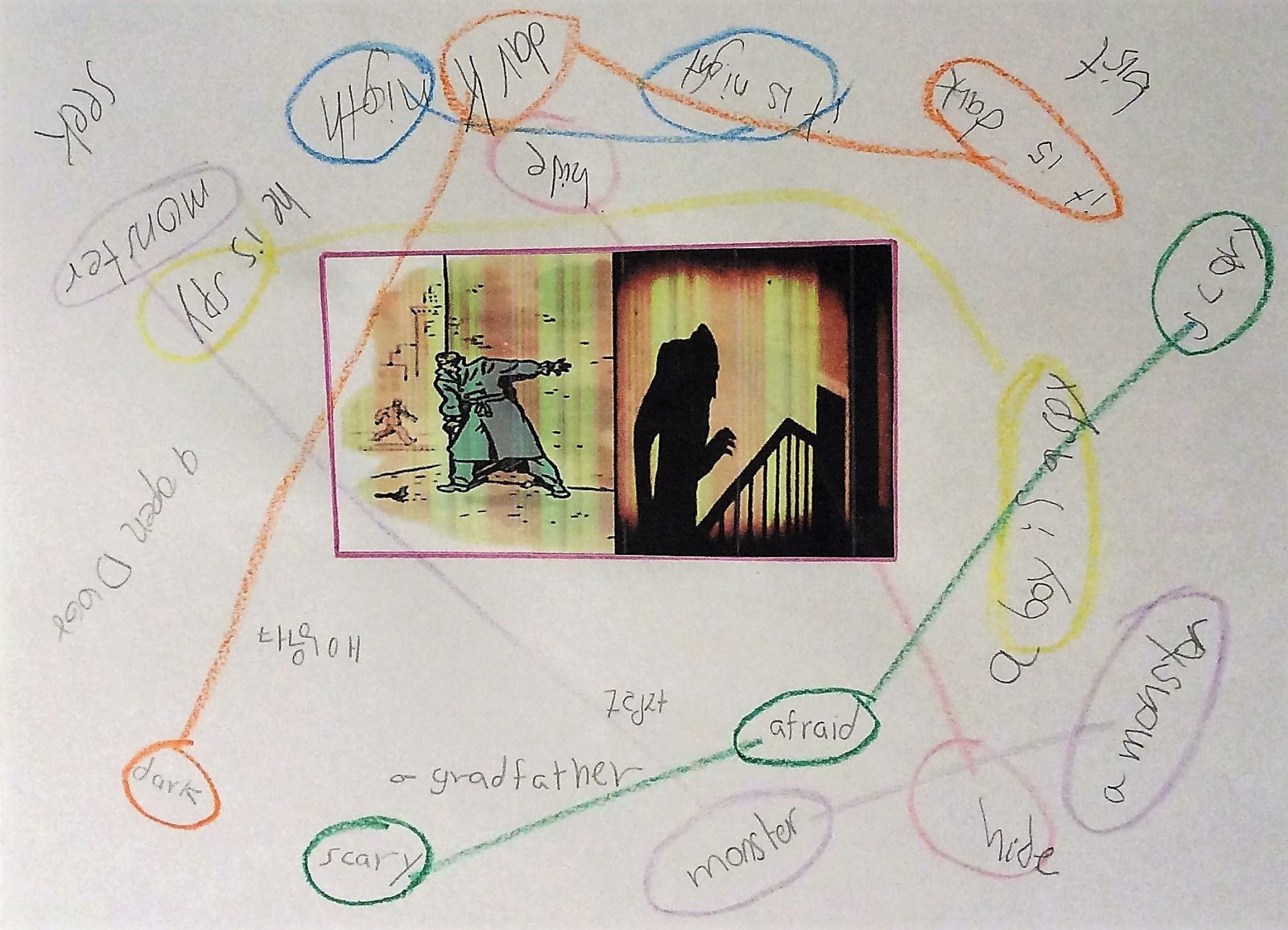

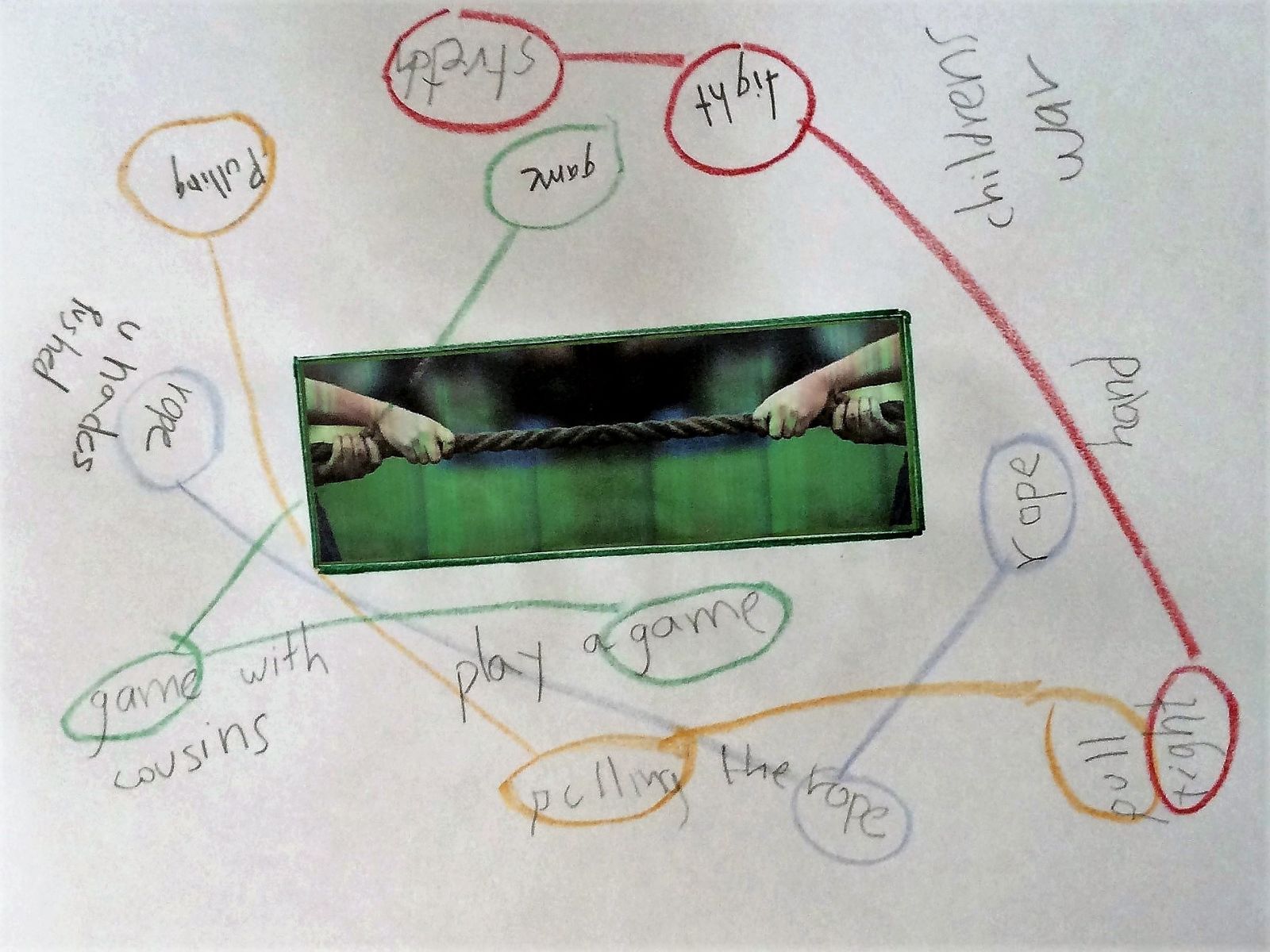

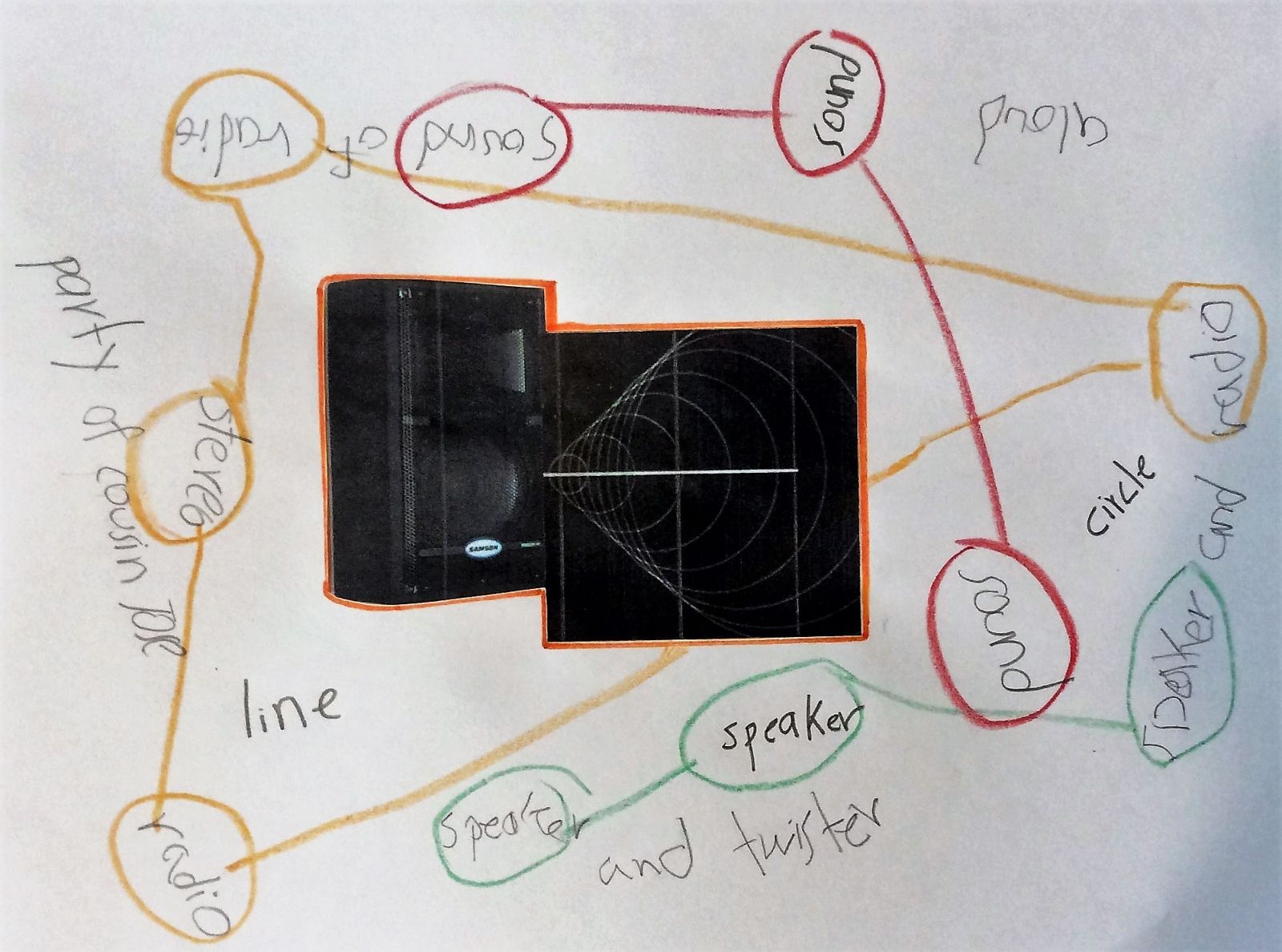

At the beginning of the class, four pictures were selected to illustrate the key vocabulary words of the lesson: lurk, untangled, resounded, and taut. Then, each picture was taped to the center of a piece of paper and the students were asked to write down everything that came to mind when they saw those pictures. In this step, learners were encouraged to record words in both their native language (in this case Spanish/Korean) and English. After that, students had to identify common ideas by circling them and connecting them with a line as seen in Figures 7-9. Finally, students discussed what they wrote and shared it with the class.

Figure 7. Linking Language: Sample # 1

Figure 8. Linking Language: Sample # 2

Figure 9. Linking Language: Sample # 3

What were the obtained results?

Figures 7-9 present evidence of background knowledge and previous experiences of all learners. For instance, student # 3 used Korean, her native language, to explain the ideas and words that came to her mind when she saw the pictures. Based on her previous performance in class, it was perceived that this student had advanced cognitive and academic skills. Besides, she had a great wealth of prior knowledge. Thus, it was necessary to transfer that knowledge from Korean to English. If she received language support to make connections between L1 and L2, she could easily succeed. That is why, when the vocabulary words of the lesson were presented, the translation from English to Korean (taut means ìž ë³µ, untangled means 풀다, resound means 울리다, and lurk means 숨어) was included. As a result, she could easily understand all the words and start using them in sentences.

This strategy also contributed to gain insights about student # 1. This student was reported to have reading disabilities and to need language support. Nevertheless, this child was a bright learner and worked very hard in all the classes. During the linking language activity, he was the student who used the most words to describe the pictures. Actually, many of the ideas he wrote in the linking language activity were used to explain the vocabulary words of the lesson. At the end of the class, he could easily understand the key vocabulary and felt that his ideas were an important and useful contribution to the class.

Finally, student # 2 had the ability to connect every single word or idea he learned in class to previous personal experiences Thus, during the linking language activity, instead of writing descriptions of the pictures, he included examples of real-life situations in which he had seen the objects or actions depicted in the photos. For example, one of the pictures used for this activity presented a “stereo” to represent the word “resounded”. In this picture, the student wrote: “the party of my cousin José”. He connected the picture of the stereo to the party he had attended the previous weekend. Therefore, when we explained the vocabulary words, we included examples related to the situations he described in some of the pictures. As a result, the content of the lesson was meaningful to him because he could make real connections between the words taught in class and his real life.

As seen in this case, diagnostic assessment should not only occur at the beginning of the school year. It should be used in every lesson as instructors begin to introduce new vocabulary words, language explanations, or content topics. Pre-assessment serves as the “dip stick” that helps teachers to know where to begin the lesson and provides anchors for linking or classifying new learning throughout the class (Herrera et al., 2014). That is why learners should be assessed through authentic strategies like the one presented above throughout the entire school year. In this case, the results obtained through the Linking Language activity allowed the teacher to elicit the students’ background knowledge and connect it to the lesson.

Students at all levels of language proficiency can participate in this kind of pre-assessment activity because they are allowed to use their native language and simple labels in English. Besides, students are in a low-risk atmosphere because there is no “right” or “wrong” answer, and everybody shows respect towards others’ ideas, opinions, and perspectives. As a result, all can participate fully and demonstrate their knowledge and skills with confidence.

In general, this pre-assessment tool can be used at the beginning of any lesson to introduce new vocabulary words, language explanations, or content topics. It is suitable not only for less proficient learners as exemplified in this article, but also for intermediate and advanced students. Regardless of their proficiency level, all learners need visual cues, meaningful content, or L1 connections to learn a second language, and that is exactly what this tool provides.

Benefits of Pre-Instructional Student Assessment

Even though these instruments were applied with a group of students of an ESL Pull-Out program in United States, ESL/EFL students worldwide can obtain similar benefits from the use of these pre-assessment tools. All students, no matter the country of origin, benefit when instruction is adapted to their linguistic, sociocultural, academic, and cognitive needs; and the best way to obtain information about these needs is through authentic pre-assessment strategies as the ones analyzed throughout this paper.

The information gathered from pre-assessment is critical for appropriately accommodating ESL/EFL students in the classroom (Herrera et al., 2013; Kim, 2015). Regarding the academic and linguistic areas, pre-assessment contributes to inform planning and instruction, connect new learning to prior knowledge, design lessons that are authentic and meaningful for learners, address misconceptions and gaps in students’ understanding, avoid redundancy or repetition of topics that they already master, challenge students and push them to develop higher-order thinking skills, and determine the areas in which students still struggle to identify practical strategies that will help them to succeed. In the cognitive area, pre-assessment allows instructors to identify the learning styles and cognitive abilities of students. Based on that information, it is possible to implement Multiple Intelligences[1] across the curriculum in order to let students demonstrate their knowledge and skills in diverse ways (Gardner, 2011), as well as differentiate assignments by modifying the length, difficulty, and time span of the task according to the needs of learners (Cushner, McClelland, & Safford, 2015). Educators can even give students the opportunity to try different types of activities and materials based on what they consider interesting and motivating (Burden, 2013). For example, they can incorporate visuals and manipulative tools such as collages, posters, role-plays, and pictures in addition to the typical textbooks used in class, or include learning centers, projects, and cooperative-group activities in addition to the traditional lectures and oral explanations.

The diagnostic assessment of students’ sociocultural background contributes to take students’ primary culture and patterns of socialization, and include them in the classroom. For instance, teachers can try to use culturally relevant strategies, topics, and materials such as books and articles that affirm cultural identities, and foreign films that give students the opportunity to explore cultures, geographical regions, and historical events (Holmes, Rutledge & Gauthier, 2009). In that way, the content and tasks prepared for the classroom will be meaningful and relevant for the students and they will be motivated to learn.

Finally, the information collected through pre-instructional assessment helps instructors to identify the personality of students and determine what makes them laugh, what annoys them, and what practices are appropriate or inappropriate according to their sociocultural perspective.

Conclusion

In conclusion, every student brings to the classroom a unique set of experiences and background knowledge that he or she can share (Herrera et al., 2013; Tomlinson, 2014). The key is to access those experiences. As explained throughout this article, pre-assessment is essential to teach ESL/EFL students effectively. Before planning instruction, it is necessary to understand the knowledge and skills that students already have (Herrera et al., 2013). The traditional pre-tests that many teachers use, often cause higher levels of anxiety, raise the students’ affective filter, and provide an inaccurate representation of students’ knowledge and abilities (Carless, 2012; Krashen & Bland, 2014). That is why it is important to use a wide variety of formal and informal assessment tools to obtain accurate information about students’ academic, cognitive, linguistic, and sociocultural backgrounds.

Nevertheless, all the information collected through these types of tools is valuable only if it is constantly used to make informed decisions about planning and instruction. Diagnostic assessment should not only occur at the beginning of the school year, it should be used in every lesson as teachers begin to introduce new vocabulary words, language explanations, or content topics. Pre-assessment serves as the “dip stick” that helps teachers to know where to begin the lesson and provides anchors for linking or classifying new learning throughout the class (Herrera et al., 2014). That is why it is important to continue evaluating students in these four areas (cognitive, academic, linguistic, and sociocultural) throughout the school year as needed.

References

Berg, H., Petrón, M., & Greybeck, B. (2012). Setting the foundation for working with English language learners in the secondary classroom. American Secondary Education, 40(3), 34-44. doi: https://www.jstor.org/stable/43694139

Bloom, B. S. (1984). Taxonomy of educational objectives: Cognitive domain. New York, NY: Addison Wesley Longman.

Burden, P. (2013).Classroom management: Creating a successful K-12 learning community (5th ed.). Hoboken, NJ: Wiley.

Carless, D. (2012). From testing to productive student learning: Implementing formative assessment in Confucian-heritage settings. New York, NY: Routledge.

Cushner, K., McClelland, A., & Safford, P. (2015). Human diversity in education: An intercultural approach (8th ed.). Boston, MA: McGraw-Hill.

Dalton, S. S. (1998). Pedagogy matters: Standards for effective teaching practice. Santa Cruz, CA: Center for Research on Education, Diversity & Excellence. Retrieved from: http://escholarship.org/uc/item/6d75h0fz

Faruk, O., Guzel, D., Koroglu, M., & Ilhan, H. (2012). Bloom’s revised taxonomy and critics on it. TOJCE: The Online Journal of Counselling and Education, 1(3), 23-30.

Gardner, H. (1983). Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences. New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gardner, H. (2011).Frames of mind: The theory of multiple intelligences (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Basic Books.

Gass, S., Behney, J., & Plonsky, L. (2013). Second language acquisition: An introductory course (4th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Ghraibeh, A. (2012). Brain based learning and its relation with multiple intelligences. International Journal of Psychological Studies, 4(1), 103. doi: https://doi.org/10.5539/ijps.v4n1p103

Herrera, S. (2015). Biography-driven culturally responsive teaching (2nd ed.). New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Herrera, S., Cabral, R., & Murry, K. (2013). Assessment accommodations for classroom teachers of culturally and linguistically diverse students (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Herrera, S., Kavimandan, S., & Holmes, M. (2012). Crossing the vocabulary bridge: Differentiated strategies for diverse secondary classrooms. New York, NY: Teachers College Press.

Herrera, S., & Murry, K. (2016). Mastering ESL/EFL methods: Differentiated instruction for culturally and linguistically diverse (CLD) students (3rd ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Herrera, S., Pérez, D., & Escamilla, K. (2014). Teaching reading to English language learners: Differentiated literacies (2nd ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn & Bacon.

Holmes, K. P., Rutledge, S., & Gauthier, L. R. (2009). Understanding the Cultural-Linguistic Divide in American Classrooms: Language Learning Strategies for a Diverse Student Population. Reading Horizons, 49(4). Retrieved from https://scholarworks.wmich.edu/reading_horizons/vol49/iss4/4

Homel, J., & Ryan, C. (2014). Educational outcomes: The impact of aspirations and the role of student background characteristics. Adelaide, Australia: National Centre for Vocational Education Research.

Igoa, C. (2013). The inner world of the immigrant child. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kim, A. (2015). Exploring ways to provide diagnostic feedback with an ESL placement test: Cognitive diagnostic assessment of L2 reading ability. Language Testing, 32(2), 227-258. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177%2F0265532214558457

Krashen, S., & Bland, J. (2014). Compelling comprehensible input, academic language, and school libraries. CLELE Journal, 2(2), 1-12.

Kucer, S. B. (2014). Dimensions of literacy: A conceptual base for teaching reading and writing in school settings (4th ed.). New York, NY: Routledge.

Tedick, D. J. (Ed.). (2013). Second language teacher education: International perspectives. New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Thomas, W. P., & Collier, V. P. (2012). Dual language education for a transformed world. Albuquerque, NM: Dual Language Education of New Mexico–Fuente Press.

Tomlinson, C. A. (2014). The differentiated classroom: Responding to the needs of all learners (2nd ed.). Alexandria, VA: ASCD.

[1]Multiple Intelligences: It is a theory that says that there are multiple types of human intelligence, each representing different ways of processing information: visual-spatial, bodily-kinesthetic, musical, naturalistic, linguistic, interpersonal, intrapersonal, logical-mathematical (Gardner, 1983, 2011).