Introduction

Pictologics (PLS) is a teaching method (Shirban Sasi, 2012) which has been tested successfully in various contexts (e.g., Shirban Sasi, 2003). Pictures are the main tools used in this method. The author was first inspired by playing cards.People may play with cards for several hours and not even feel the passage of time. If we can create such an effect in language classes, then that will be a great help for both teachers and students. The basic question is: What is that makes it possible to play with cards for several hours without tiring?

In my opinion, there are two reasons (Shirban Sasi, 2012):

2. The value of each card is not absolute; that is, based on different games, different values are attributed to each individual card. (p.103)

These two characteristics, if adapted to pictures, will give the teacher and students a good opportunity to teach and learn the language.

Usage of Pictures in EFL/ESL

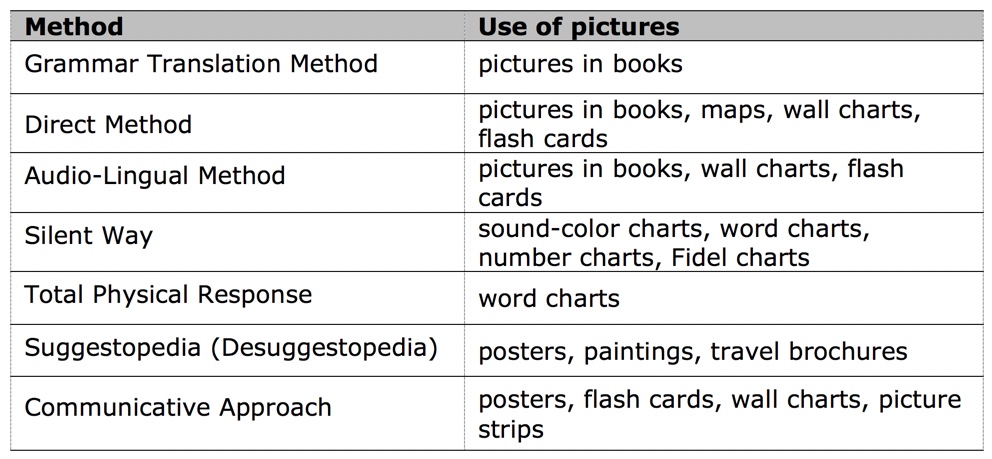

Pictures have been used in various language teaching methods and approaches. Table 1 lists the use of pictures in some of the most popular language teaching methods and approaches (Larsen-Freeman & Anderson, 2011).

Table 1. Use of pictures in EFL/ESL methods.

Concerning Table 1, we can see that pictures are mostly used in books, or as a part of larger classroom props, such as brochures, posters, or charts. So, the only exclusive usage of pictures in card forms are flash cards and picture strips. Flash cards are often pictures of objects or actions. Sometimes, the name of the object or action is also written below or on the back of the card. Mostly, these pictures are used to teach words to beginners, particularly to children and teenagers. On the other hand, a picture strip is usually a combination of three to six pictures that are vividly connected. Students are asked to relate the pictures with another student and come up with a short story. Picture strips are mostly used in intermediate or advanced classes, and in general English tests (Larsen-Freeman & Anderson, 2011).

The Role of Imagination

The concept of imagination has not been much utilized in other methods. Only in Desuggestopedia (Brown, 1987; Larsen-Freeman & Anderson, 2011) can we see that a new imaginary identity is given to the students. Even here, the focus is not on imagination, but rather on hypnosis. As far as other methods are concerned, the author assumes that imagination is used in short role-plays, and some limited visualization in written language skills i.e., reading and writing (Mayfield, 2004; Peach & Burton, 1995).

In literature and art, however, imagination has an important role. When listening to music, reading a novel, looking at a painting, or touching a sculpture, we can enjoy that piece of art more if we use our imagination. By using our imagination, we can travel in time and place, and cross boundaries. According to Arnheim (1997), understanding works of art involves aesthetic perception. This helps us deconstruct our vision towards the language, as poets or other literary people always do. According to Peach and Burton (1995), languages do not deal with absolute reality; rather, we should ‘deconstruct’ what might be taken as the perfect truth. Also, according to Eisner (1994), teaching can be regarded as ‘art’. This vision would lead us to a deeper understanding of what has surrounded us in this world where language is just a part of it. According to Chomsky (as cited in Mayfield, 2004), “The beginning of science is the ability to be amazed by apparently simple things” (p.16).

Likewise, Pictologics is a way of thought communication. It is based on the following assumptions (Shirban Sasi, 2004a):

- The human mind is capable of thinking about almost anything.

- There is no limit to our imagination.

- We can perceive the world around us with at least one of the five senses of hearing, sight, smell, taste, and touch.

- With just a few pictures, we can have endless combinations of pictures by which we can make/utter/write (communicate) endless structures/pieces of information. (p.3)

Critical Thinking and PLS

Associating meanings to pictures through imagination, and then being ready to explain why we made this association are in concordance with the definition of critical thinking skills offered by most advocates in the field. As the author’s experience with Malay students shows, successful PLS language learners have frequently been reported to be successful achievers in other disciplines as well (Shirban Sasi, 2012). Therefore, in this section we will have a brief look at how critical thinking has been viewed in the literature.

Lipman (1988) believes that critical thinking is “skillful, responsible thinking that facilitates good judgment” (p. 39). Halpern (1998) defines critical thinking as, “the use of those cognitive skills or strategies that increase the probability of a desirable outcome” (p. 450). Also, Willingham (2007) defines critical thinking as “seeing both sides of an issue, being open to new evidence that disconfirms your ideas” (p. 8). Finally, according to Nakagawa (2011), “Critical thinking has been regarded as the power of talented people and the source of innovation” (p. 582).

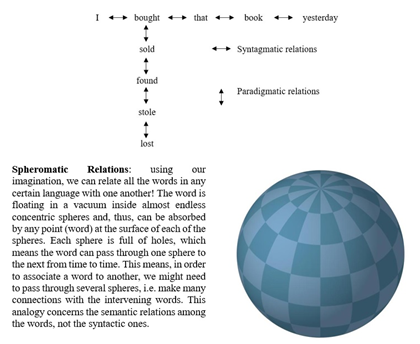

Thus, in the light of the theory of critical thinking, and also based on the various PLS techniques which make use of its underlying assumptions, the author suggests a hypothetical model in which, in addition to the sequential (syntagmatic) relations among the words, as well as the substitutional (paradigmatic) relations (Richards, Platt, & Platt, 1992), a third type of relation (i.e., semantic relations) exists among all the words in any given language. He has dubbed it spheromatic relations. Figure 1 demonstrates the three-dimensional quality of the proposed model, as opposed to the more limited syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations.

Figure 1. Spheromatic relations as juxtaposing syntagmatic and paradigmatic relations (adapted from Shirban Sasi, 2012, p.62).

Definition of Pictologics

The word Pictologics is made up of three parts: picto, logic, and s. let’s begin with picto which is the short form of picture. This has two meanings: as a noun, it means pictures of different subjects such as people, nature, animals, food, signs of technology, different places, etc. Totally, there are just 300 pictures that are used for all levels. Most of these pictures, including the ones used in this article, were chosen either from the Internet public domain, permitted by the owner, or else photographed by the author. ‘Picture’, as a verb, means to ‘visualize’ or to ‘imagine’. Via imagination, we can travel in time and place. What we do in the classes is, first of all, to teach the language learners how to control and then benefit from their imagination. To do so, we teach the students to pay attention to their more concrete senses: sight, hearing, smell, taste, and touch. Logic, on the other hand, means whatever word(s) or pieces of information that we can connect-directly or indirectly- to a certain picture or/and set of pictures picked randomly. Finally the s is a suffix which gives the whole word a noun form. Picto is the short form of ‘picture’. Please look at the following example (Photograph 1) of a photograph of a person. This can be any person. We might or might not know him. He can be of any age, race, color, or any other attributes a male human being can possibly possess. In Pictologics, one can think of almost any structure using a picture such as the example.

Photograph 1. An example of a person (internet).

- I, He

- Ali, Jack, (any masculine names)

- Mr. (X)

- My (any male relatives)

- My (teacher, boss, …)

- The (teacher, driver, …)

- The (young, …) (teacher, …)

- The man wearing a …

The words and language pieces above are considered “logical” and thus, accepted in Pictologics. There can be almost endless linguistic pieces which can be related to the above picture if one uses his/her imagination. However, the following words and language pieces are not “logical”:

- She

- Fatima, Mary, (any feminine names)

- Mrs. (X)

- My (any female relatives)

- The (actress, stewardess, …)

- The (young, …) (actress, …)

- The woman wearing a …

- The horse

- A tree

As illustrated, the limitations may be: 1) an utterance (language production) is completely in contrast with the firmly-established grammatical rules of that specific language; and 2) a language production violates the ethics of a particular culture. An example of this is some cultures do not accept comparison of a human to a horse or a tree.

Probable Number of Produced Structures

If students and teachers learn to make imaginary associations between linguistic forms and a picture or picture combinations, and if they learn to make the best of their five senses, then they can produce many structures. When we use more than one card at a time dealing with random combinations of two, three, four, and … cards, and if we can see a concept from this picture and another from that, then we will have a very large number of combinations. Therefore, there will be chances for the students to produce (both oral and written) structures, and chances for the teachers to check their students’ understanding and learning.

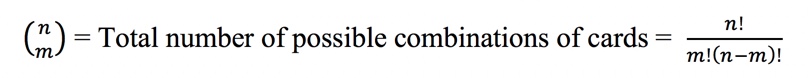

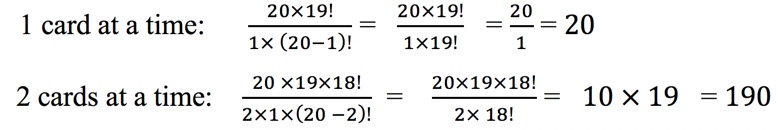

Then, in order to measure as to how many possibilities we will have, we can apply the following combination formula:

Where n= total number of the cards, m= number of the cards picked together at a time, and “!” means the figure should be multiplied by all the digits preceding it.

In the following example, we assume we are dealing with just 20 pictures in a hypothetical PLS class. Applying the formula for each possible picture combination, we will have:

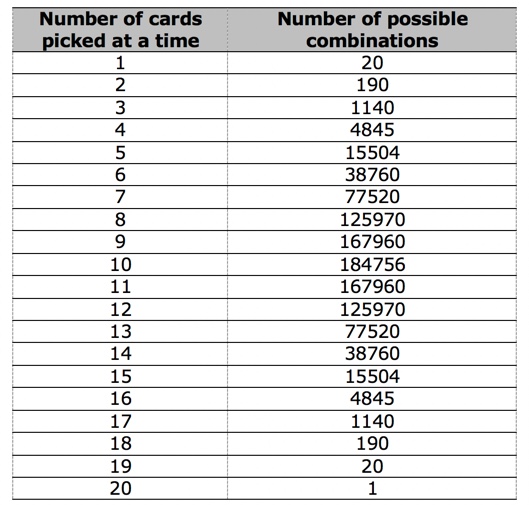

If we keep calculating for 3 cards, 4 cards, …, 20 cards at a time, Table 2 refers to the possible combinations added up. The numbers of combinations at first seem to be small; however, this gets larger towards the middle and then, slopes down to smaller numbers again. As can be seen, there is a symmetry in this calculation and the numbers scatter around the middle number (10 pictures at a time) like a mirror.

Table 2. Number of combinations using 20 pictures.

The sum of these numbers is 1,048,383. Using only 20 pictures, we will have more than one million possible combinations. Then, if we imagine that for each picture combination we can come up with only two linguistic pieces of information (beginning with single words, and going on to compound complex structures, essays, etc.), we will then have 2,096,766 possibilities! Each of these possibilities could be a good source for language production (Shirban Sasi, 2004b).

Pictures: What? How?

Pictures are picked up randomly in PLS. The pictures themselves are not important. What happens in the minds of the learners is important. Teachers usually take 50 to 60 A5-size pictures with them to the class. They can be equally used for all levels. The picture cards are placed face down on the desk. For the elementary levels, each time only one card is picked and dealt with alone. The teachers try to lead the students to connect ‘logical’ structures to each picture. Then, for the higher levels, more less-frequent vocabularies are attributed to the same pictures. Also, the number of the cards which are taken each time increases gradually in upper-intermediate and advanced levels. The current record is 35 pictures together at a time.

Grammatical Patterns

Teaching grammatical formulae is not enough. In addition, some people believe that learning conversation is separate from learning grammar. That is, it is possible to speak another language without being aware of its grammatical rules. However, the author thinks that in countries where English is not the native language, perhaps one should first learn some patterns or grammatical rules if one intends to learn the language in a reasonable period. Then, one should either learn the patterns and vocabulary, or as the followers of natural approach believe, sit down and simply receive and observe the teacher or the audio/visual aids.

The author does not deny the benefits of being exposed to the target language (e.g., English) in the above-mentioned ways. Nonetheless, PLS stresses that with learning just a few rules and patterns, it is possible to generate endless linguistic structures. This production can be both oral (i.e., conversation) and written. Our mental capacity is much more than just memorizing some rules. By analyzing the rules, we should try to produce the structures we are willing to make (Shirban Sasi, 2006). In the same way, Freire and Macedo (1987), believe students do not have to memorize descriptions mechanically. Instead, they must learn the underlying significance. They assert that mere memorization is not real reading, nor can it bring about understanding of that specific text.

Classification of the Learners in PLS

English language student can benefit from Pictologics. Knowing the English alphabet and a few words are enough to start with PLS. Nonetheless, because of the delicate relations among the language components, all students, whether elementary or advanced, should continually repeat what they have learned. Furthermore, we should that other techniques and activities currently used in the other teaching methods and approaches (Celce-Murcia, 2001;Larsen-Freeman & Anderson, 2011; Lozanov, 1978; Richards & Rodgers, 1990) can be adapted and incorporated into PLS classes. Examples of these techniques and activities are various kinds of drills, memorization, recitation, translation, composition, paragraph writing, different games, etc.

Nothing is Unimportant in PLS

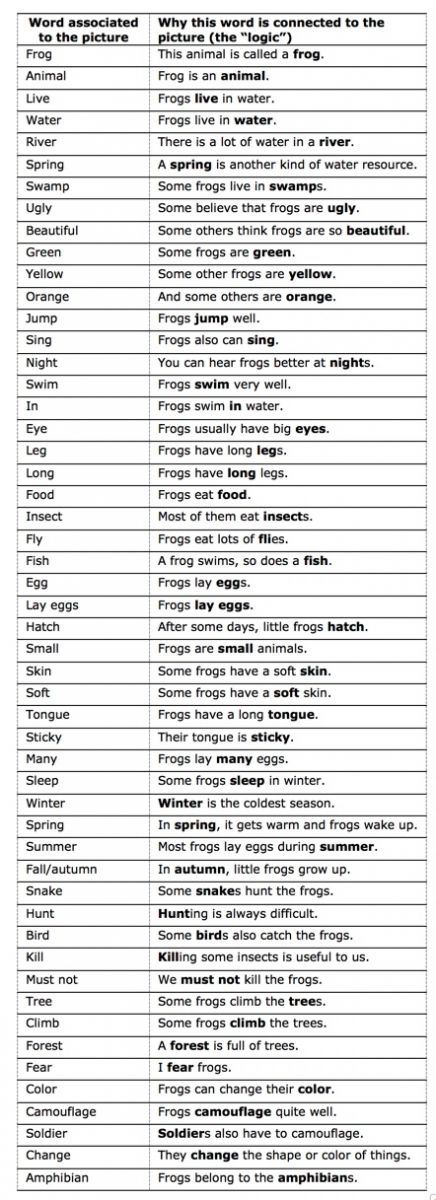

Using the following picture of a frog (Photograph 2), one can see what words or expressions are connected to it. One might think this picture is unimportant or trivial. Yet, with Pictologics, even ordinary pictures can open doors to complex connections.

Table 3 shows how easy it is to think about these words, directly or indirectly (adapted from Shirban Sasi, 2004b, pp. 112-115).

Table 3. Examples of words associated imaginatively to a simple picture.

As illustrated, we could connect more than 50 words or expressions to this picture. Almost everybody can easily add at least another 50 words to the same picture.

Ten Activities Using Pictologics

In this section, ten activities are provided as examples. In the activities, the picture cards are placed face down on the table and are drawn randomly.

1. Take a picture card, show it to the students, and ask them what they can see. Ask them to use their imagination to connect as many ideas to this picture. Ask funny, strange, startling questions.

2. Draw a card. Do not show it to the students. Ask them whether they want you to change this picture. Ask them why they like or dislike it.

3. Ask the students to give you a word (or a piece of information) in English. Write it on the board. Then, pick a picture and ask them to somehow relate this picture to that word. Do likewise with as many picture cards as you like with the same word or piece of information.

4. Take a card and ask the students to say a word or piece of information which they believe cannot be related to that picture at all. Then, ask them to focus, use their imagination, and try to connect the idea to the picture. Give them some hints if necessary.

5. Place two pictures together and ask the students to connect them imaginatively and come up with different sentences using ideas.

6. Taking two pictures, ask the students whether they can think of any idea(s) that cannot relate to the combination of these two pictures. Then, you, as well as other students, may argue for and against their positions.

7. Take one picture. Ask the students their opinion concerning what they want as the second picture. They should be individually ready to support what they would like. Make them ask each other, argue with each other, and try to convince each other.

8. With a picture, ask the students to focus on one of their senses at a time and attribute sentences or pieces of information to that particular picture. In doing this, the students can imagine that out of the five senses, they can only use one (like hearing, or touch). Your imaginary questions and directions can be very helpful. Once they feel comfortable with one picture, move to more pictures.

9. Take one or two pictures. Ask the students to combine two of their senses (for instance, touch and vision) to produce pieces of language. Then let them try to change one of the two with another sense.

10. Gradually increase the number of the picture cards picked up each time as your students become more competent in the language and more comfortable with this method. Theoretically speaking, you can even work with 50 pictures at one point provided that you and your students have time to deal with them.

Ten Hints for the PLS Teacher

Teaching as a PLS teacher might seem difficult because the teacher may face many unpredicted scenarios. However, the following recommendation can enable the teachers to handle their classes more comfortably, as well as efficiently. The author’s experience has shown that teaching with this method is fun for both teachers and students.

1. Try to be as imaginative as possible. Note that in PLS even the sky is NOT the limit!

2. As you are imaginative, let the students be imaginative as well. Remember, there are only two limitations: ethics, and strict grammatical rules.

3. Do not forget to upgrade your general knowledge. The more you study, the more easily you can handle the class.

4. Your whole mind should be present in the class.

5. When avoiding ethical problems, try to keep as neutral as possible, and make students manage their feelings.

6. Show curiosity and interest in what students produce.

7. Have fun with the students as much as the class allows.

8. Remember that almost anything is possible in PLS classes. Be ready to listen to your students’ strange opinions.

9. Do not be afraid if students ask something, such as vocabulary, which you are unsure about. Nobody is perfect. It is important for the students to know you can present and teach them, and that you can do it professionally.

10. Keep in mind that pictures are the triggers, the starters, and the instigators. You should not limit yourself to the sense of vision. With or without it, you can almost always make use of the other senses individually or collectively to tackle a picture or a combination of pictures.

Practical Concerns of PLS

From the start of PLS classes, a number of practical issues have been brought up. PLS is both deductive and inductive, and mostly focuses on the productive skills of speaking and writing. The use of mother tongue is allowed in PLS, yet the amount of L1 should decrease progressively with a gradual shift to the target language. Errors are dealt with cautiously. If language errors are not fossilized in the students’ minds, the teacher can wait for a good occasion to make the correction. Even in doing so, the PLS teacher should make the best of his/her imagination as well as the students’ to illustrate the appropriate linguistic productions. Regarding student assessment, many assessment tools from other methods can be adapted and used in PLS. Examples of these tools are oral interviews, multiple-choice exams, open-ended items, and cloze tests. What is important is that we should focus on the students’ imagination when adapting these instruments. Finally, it should be emphasised that PLS certainly makes use of many techniques, and procedures used in the other methods.

Conclusion

This article has provided readers with experiences in developing the Pictologics method based upon theory and practice. It was argued that PLS helps students become more focused and enthusiastic, as well as becoming more critical thinkers. Both the teacher and student are creative participants in the class. The author hopes teachers will explore the use of PLS and have first-hand experience as to the benefits of this method.

References

Arnheim, R. (1997). Visual thinking. Berkeley, CA.: University of California Press.

Brown, H. D. (1987). Principles of language learning and teaching (2nd ed.).Englewood Cliff, NJ: Prentice-Hall, Inc.

Celce-Murcia, M. (Ed.). (2001). Teaching English as a second or foreign language (3rd ed.). London, UK.: Thomson Learning, Inc.

Eisner, E. (1994). The educational imagination: On the design and evaluation of school programs. New York, NY.: Macmillan.

Freire, P., & Macedo, D. (1987). Literacy: Reading the word and the world. London, UK.: Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd.

Halpern, D. F. (1998). Teaching critical thinking for transfer across domains: Dispositions, skills, structure training, and metacognitive monitoring. American Psychologist, 53(4), 449–455.

Larsen-Freeman, D., & Anderson, M. (2011). Techniques & principles in language teaching (3rded.). Oxford, UK: Oxford University Press.

Lipman, M. (1988). Critical thinking—What can it be? Educational Leadership, 46(1), 38–43.

Lozanov, G. (1978). Suggestology and the outlines of Suggestopedy. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Gordon and Breach Publishers.

Mayfield, M. (2004). Thinking for yourself: Developing critical thinking skills through reading and writing (6th ed.).Boston, MA:Heinle & Heinle Publishers, Inc.

Nakagawa, T. (2011). Education and training of creative problem-solving thinking with TRIZ/USIT. Procedia Engineering, 9, 582-595.

Peach, L., & Burton, A. (1995). English as a creative art: Literary concepts linked to creative writing. London, UK.: David Fulton Publishers.

Richards, J. C., Platt, J. T., & Platt, H. (1992). Longman dictionary of language teaching and applied linguistics. London, UK.: Longman.

Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. S. (1990). Approaches and methods in language teaching: A description and analysis. Cambridge, UK.: Cambridge University Press.

Shirban Sasi, A. (Designer), & Kalantari, J (Director). (2003). Let’s Learn English.[Educational TV Program]. Tehran: Educational Channel of the Islamic Republic of Iran Broadcasting.

Shirban Sasi, A. (2004a). Final report on “PICTOTHERAPY”: Training secondary school teachers for re-establishing communication skills. Bam City: 8-10December, 2004. Submitted to UNESCO Tehran Cluster Office.

Shirban Sasi, A. (2004b). Pictologics system, elementary: Textbook. Tehran: Peyk-e Zaban Publishers.

Shirban Sasi, A. (2006). Pictologics system, intermediate: Textbook. Tehran: Peyk-e Zaban Publishers.

Shirban Sasi, A. (2012). The effects of applying Pictologics (PLS) method on English vocabulary learning by Malaysian year six primary school students. Unpublished Ph. D. thesis, University Sains Malaysia, Malaysia.

Willingham, D. T. (2007). Critical thinking: Why is it so hard to teach? American Educator, 8-19.