Introduction

Incorporating English as a Foreign Language (EFL) at university is necessary so that learners’ professional activity or occupation is better recognized globally (Crystal, 1997; Dudley-Evans & St John, 1998). In the case of Mexican autonomous public universities, most of the English and teaching programs have focused on teaching the language for general purposes. There is no evidence of students’ satisfaction or English level at the end of such instruction (Davies 2008 González, et al., 2004). The Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla (BUAP) , through its Institutional Management Development Plan 2013–2017 (BUAP, 2013), has stated that attaining the required English proficiency level is key to improving internationalization and promoting the mobility of students and teachers. In the university’s Modelo Universitario Minerva[1], learning a foreign language helps students connect with the global and scientific world. The university’s institutional foreign language policy states that English should be a mandatory subject within the national and international standards. Alternatively, students can take a formal evaluation where the mastery of the language is demonstrated (BUAP, 2007, p. 52). However, this scenario had some limitations. Following Criollo-Avendaño’s (2010) exploration of this language policy at BUAP, there are some challenges to be resolved; namely:

- A minority of students accomplish an A2 level.

- Many students cannot graduate because of their low performance in English.

- Students report the topics studied in English classes are repetitive or not useful.

- University professors (faculty members) recognize the importance of English but hardly ever use it in their subjects.

- English teachers lack time to research genres and adapt their classes to the students’ needs.

- There is a lack of English professionals with proper training to adapt content to each major’s context.

- There are no research projects that approach the genres used in each discursive community.

With this in mind, four EFL professionals of the Complejo Regional Nororiental in Teziutlán, Puebla, a multidisciplinary health science campus, investigated and assessed the 2014 cohort’s needs for their English courses. In this initial exploration, students, professors from different degree programs (e.g., Medicine, Nursing, Psychology, Clinical Nutrition, Stomatology, and Physiotherapy), and administrators reported English was a very important and useful language for academic, scientific, and occupational purposes. They also agreed that it was a difficult subject and expressed the need for motivation to practice and improve their language level, especially for reading scientific texts.

These preliminary results were used by the English teachers to adapt the programs from Level 1 to 4 using the English for specific purposes (ESP) approach (Belcher, 2006; Paltridge & Starfield, 2014). Task-based language teaching (TBLT) was used to implement the ESP approach. Later on, after students completed their four mandatory language courses, data was collected and analyzed to assess their perceptions on how an ESP approach, along with TBLT, supported their English learning.

Literature Review

According to Dudley-Evans and St John (1998) and Widodo (2016), speaking a foreign language has become essential for success in many social activities and professions. Thus, the effectiveness of learning techniques and methods for teaching EFL must be appropriate for the students’ context. Moreover, up-to-date research on ELT (English Language Teaching) has reported that ESP has been widely used in college English courses to get closer to students’ context and address their professional needs. This aligns with what Johns and Salmani (2015) have suggested in a recent interview, emphasizing that ESP is a suitable methodology for language instruction. They also argue that the growing diversity of students’ wants in this century lead to carrying out different and reliable measuring ways to identify their current needs and context.

Using ESP involves adopting a collaborative role in which the language teacher works together with content teachers. However, this is one of the key challenges for language teachers when using this approach (Luo & Garner, 2017). When planning student-centered language instruction, the use of TBLT has been effective for beginning levels since it addresses specific students’ language learning objectives at different stages (Muller, 2005). That connection between ESP and TBLT suggests ways of developing more efficient and realistic language-learning goals within higher education curricula.

English Language Teaching in Mexican Public Higher Education

In Mexico, learning English has become a powerful academic tool for undergraduate and graduate students because of the advantages it offers for their professional development opportunities. González et al. (2004) reported significant findings in a study carried out in nine different public and private universities in Mexico City. The findings pointed out the challenges for higher education institutions to formulate effective strategies and solutions to improve students’ performance in English and build a strong and carefully planned teaching of English in the curricula that considers the demands of professional graduate profiles. Nevertheless, the inefficient English instruction in higher education, the lack of consistency in measurement procedures, and the lack of a standardized system to measure the language competence levels seems to create a complex problem that results in low motivation for learning the language (Ramirez Gómez et al., 2017).

González Robles et al. (2004) also pointed out that in Mexican public and private higher education institutions, postgraduate programs established their criteria and standards of English performance levels at the beginning and at the end of their academic programs. These varied from institution to institution. In some universities, English is not an entrance requirement, while in others, the required English entrance level could be A2 (pre-intermediate), B2 (upper-intermediate), or C1 (advanced), based on the Council of Europe’s (2018) Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (CEFR) guidelines. It all depends on whether they are public or private institutions and the field of study. Some universities have implemented specific criteria as part of their admissions exams, such as the CENEVAL EXANI II, a standardized instrument used at a national level, designed with questions on different areas, and adapted to different academic plans and degree programs. Other types of language proficiency admission exams only evaluate reading comprehension and grammar. This complex reality lacks clear language policies that would be suitable for all, or at least most students. However, new efforts and educational reforms nationwide are being made to support the improved performance of language competences (Secretaria de Educación Pública, 2017).

English for Specific Purposes (ESP)

Hutchinson and Waters (1987) described ESP as an approach for meeting learners’ needs in which the ways of delineating language, models of learning, and needs analysis are essential elements for course design. They also emphasize the need to design a syllabus, material, and methodology that can be implemented and evaluated. The ESP approach was originally conceived in the early 1960s to describe the rules of English grammar. Since then, in response to constantly changing demands in a globalized world, ESP has changed to a particular approach in which special needs, specifically professional, are satisfied. ESP is focused on meeting learners’ particular language-learning needs within a specific discipline or occupation (Belcher, 2006; Hyland, 2007). In Mexico, specifically, ESP in higher educations has been discussed by Davies (2008), who suggested that English instruction in this context should be mainly mediated through ESP, rather than English for General Purposes (EGP). He argued that ESP is especially needed in public education since students are already grouped into occupational areas in which they need to develop as professionals.

Understanding and analyzing students’ needs is vital in an ESP teaching context. One of the main contributions of ESP to the eclectic world of ELT has been the needs analysis. This can be a vital asset in helping ESP teachers understand their students’ basic needs, based on their weaknesses (Alsamadani, 2017; Strevens, 1988). Therefore, some researchers argue that successful ESP instruction depends on first recognizing the learners’ needs (Cowling, 2007; Taillefer, 2007). Also, a needs analysis should be useful for students who want to get the best of their curricula since their instructors are aware of their wants and desires when learning something new (Carkin, 2005; Chamot, 2007). Carrying out needs analysis is a complex task because of the need for data collection and follow-up with learners and other actors to define realistic learning objectives for ESP. However, needs analysis is the foundation on which we can develop pedagogical content, teaching materials, and methods that can support increased learners’ success and motivation (Otilia, 2015).

Task-Based Language Teaching (TBLT)

TBLT has been a matter of discussion and research in the ELT field since the late 1980s, as reported by Ellis (2009). The notion of task was related to various terms such as teaching, learning, language acquisition, grammar exercises, and oral production. The term was initially connected to learning, identified as an approach to meaningful student-centered activities for language use (Ellis, 2003; Skehan, 1998; Willis, 1996). Then, as the approach gained recognition, it became widely used among English teachers worldwide (Ellis, 2009; Long, 2014). TBLT is “an approach to teaching a second/foreign language that seeks to facilitate language learning by engaging learners in the interactionally authentic language use that results from performing a series of tasks” (Ellis, 2013, p. 1). According to Ellis (2009) and Rubin (2015), TBLT has been an effective means for teaching English for almost 30 years, as it has clear and precise pedagogical characteristics.

Moreover, Ellis (2009) and Rubin (2015) suggested that, in this methodology, tasks should be realistic activities with a focus on students’ use of language, centered on a communicative target (Ellis, 2003; Rubin, 2015). It is important to emphasize that one strength of TBLT is that it considers the learner’s experience to achieve effective learning through tasks (Ellis, 2009). Ellis (2013) defined a task as “work plans that provide students with the materials they need to achieve a specified result in communicative and non-linguistic terms” (pp. 1-2).

For Rubin (2015, p. 23), “tasks are always activities where the target language is taught for a communicative purpose (goal) in order to achieve an outcome.” Jarvis (2015) took Ellis (2003) as a basis to define tasks as work plans that include four key criteria: the first criterion focuses on meaning, the second considers that there is some gap, the third is related to the students’ need to use their own linguistic and non-linguistic resources, and the fourth establishes that there is an outcome other than a display of language. O’Connell (2015) argued that there are two kinds of tasks: target tasks and pedagogic tasks. The first type involves real-world activities using the language, while the latter are instructional tools to perform a target task effectively. These definitions provide the elements necessary to understand TBLT as a popular and flexible work plan. As seen, authors such as Ellis (2003; 2013) and Rubin (2015), and Jarvis (2015) include in their definitions of task key concepts such as “real word activities,” “meaning,” and “communicative purposes.” Córdoba Zúñiga (2016) noted that “new trends in language teaching and learning try to promote communicative competence instead of mastering grammar, vocabulary, reading, writing, or listening in isolation” (p. 14). Accordingly, TBLT could be understood as a method that prioritizes communication rather than mastering isolated language skills.

Since TBLT focuses on communication and meaning, it is necessary to describe the phases through which it is implemented to understand better how TBLT promotes communication and meaning. According to Willis (1996), Jarvis (2015), and Anwar and Arifani (2016), there are three key steps to perform a task: the pre-task, the during-task, and the post-task stages. The pre-task stage presents an overview of the task to the students and, they receive the instructions and get to know the objectives of the task. In the during-task stage, students analyze how to carry out the task and complete it. In this stage, the teacher’s guidance is essential for students because they may need feedback. Finally, during the post-task stage, students correct their mistakes and improve their tasks to optimize them.

In this study, TBLT was used to design speaking and writing activities with a communicative purpose in which the target language was an instrument used to complete them. Thus, the task was an activity in which students used the target language to communicate in a context. This task had to involve real-life topics or problems in which interaction was promoted for decision-making processes. These were also guided activities connected to games, problem-solving techniques, and students’ experience so that the task integrated other meaningful events to reach a communicative purpose (Ellis, 2003; 2009; Long, 2014).

A Mixed-Method Orientation for Needs Analysis

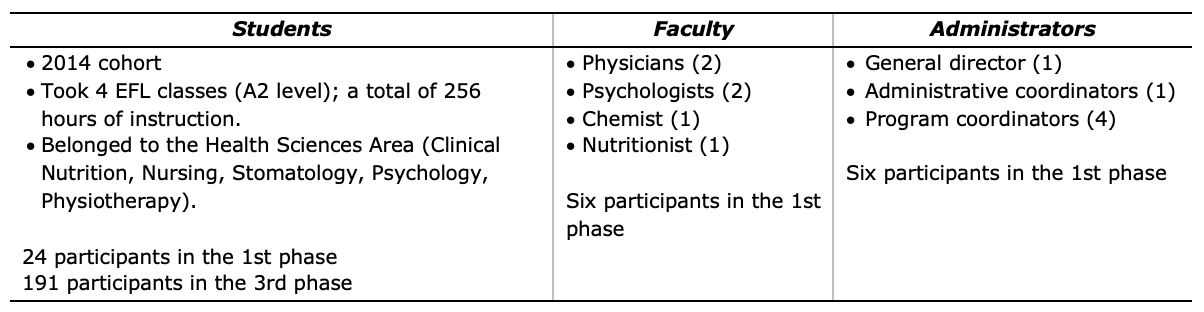

This study adopted an exploratory sequential research design (Creswell, 1999) within a needs analysis lens (Fatihi, 2003; Seedhouse, 1995; Watanabe, 2006). It used both qualitative and quantitative data to identify the needs of the 2014 cohort in three phases. A non-probabilistic questionnaire was used to collect opinions from students, faculty, and administrators for the decision-making process in developing the analytical syllabi. Next, a proposal was developed and piloted with a syllabus that integrated communicative learning objectives within the health sciences field. Finally, quantitative data were collected to assess the students’ satisfaction level after finishing the four mandatory EFL courses of the first generation. Table 1 summarizes the characteristics of the participants in the study.

Table 1: Participants’ characteristics

First Phase: Initial Exploration

A needs analysis questionnaire for students was used to collect information that could be organized and analyzed systematically (Taylor-Powell, 1998). Twenty-four questions were used to collect data on students’ backgrounds and expectations regarding the target language, including personal/demographic information, previous English learning experiences, learning strategies, study habits, insights on the usefulness of English in their profession, and their interest in getting a certification in English (see Appendix 1). The questionnaire was revised and piloted with students and teachers before being implemented. As a result of piloting, items were not modified since all the questionnaire items were useful in providing a richer context for students’ data.

A separate questionnaire was also administered to 10 professors. It had 15 open questions focused on identifying the needs of a professional in the health sciences. This questionnaire was divided into three sections. The first section was intended to obtain general demographic information about the professors, such as their specialization, degree programs they had taught, and their opinion about the target language. The second section addressed their English learning experiences in higher education. The third section focused on their experiences using the target language professionally and academically (see Appendix 2).

Additional data were collected through interviews with six university campus coordinators. The primary goal of these interviews was to collect reflections on needs in English instruction from the point of view of these key authorities in this context. The interviews were administered to four program coordinators belonging to the Psychology, Nursing, Clinical Nutrition, and Stomatology degree programs and the general administrator and campus director. The interviews were conducted in Spanish; seven questions were asked, and the participants’ answers were audio-recorded. Later, their recorded responses were transcribed into digital text and analyzed to find emergent categories related to the needs identified (see Appendix 3).

The main results obtained from the first phase showed that students, faculty members, and administrators agreed on the importance of learning English for academic and scientific purposes. Reading scientific texts was reported as the most important skill that students needed to master. Interestingly, students reported having studied English for about six years; yet, several students had unsatisfactory English learning; the vast majority came from public schools. All of them were interested in getting a certification in English.

Second Phase: A TBLT within ESP Proposal

Based on the information collected in the first phase, a pedagogical proposal to approach TBLT within an ESP methodology was developed (see Appendixes 4 and 5). This new curriculum was piloted from the Spring of 2015 to the Fall of 2016. It was comprised of an analytical syllabus that integrated some of the most relevant results from the questionnaires and interviews administered in the first stage of the study. Based on those results, the new curriculum was designed with the following characteristics:

- creating contextualized learning activities (tasks) addressing students’ reported needs, interests, and learning styles regarding communication in English;

- facilitating reading strategies to help students understand and interpret information from different texts (spoken and written);

- scaffolding structures and vocabulary in a context to facilitate language learning; and

- adapting materials from authentic scientific sources (journals, magazines, books, etc.) in English.

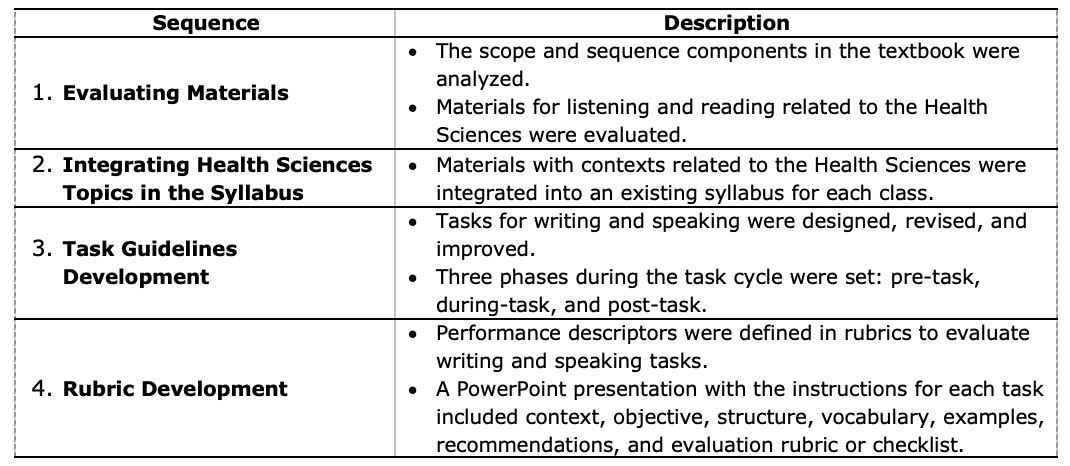

Table 2 describes the steps followed to design and implement ESP materials in courses (see Figures 1 & 2).

Table 2: Materials development and implementation

Third Phase: Assessing Students’ Perceptions

After completing their four language courses, 455 students from the 2014 cohort belonging to the General and Community Medicine, Nursing, Clinical Nutrition, Physiotherapy, Stomatology, and Psychology degree programs were invited to complete a survey with Google Forms. Participation was voluntary, and 191 responses were received, from which 112 participants were females, and 79 were males. The survey was designed with twenty questions using Likert-scale questions and one additional open question for comments. This instrument aimed at finding students’ opinions about using tasks (Ellis, 2003), self-assessing themselves on the CEFR can-do statements in the four skills, and using English in the courses within their degree programs. The items for each section in the questionnaire were developed to help reach conclusions regarding the different needs identified in the first phase and the materials implemented in the second phase. Additionally, it was vital to ask students to reflect on their self-assessment regarding their language performance through can-do statements at an A2 level, the expected learning outcome (see Appendix 6).

Results

The most significant results of this study were derived from the first and third phases. This was to compare and contrast the needs and expectations of students, faculty members, and administrators in Level one with the students’ perceptions after completing their fourth EFL course. These are the needs identified, followed by the findings showing a positive overall perception of the TBLT approaching ESP work methodology.

Needs Identified in the First Phase

In the first phase, the requirements of the English teaching-learning context were identified. It was a preliminary exploration that allowed the researchers to obtain qualitative information about the perception of students, faculty members, and administrators regarding their English learning wants, desires, previous experiences, and expectations in the different health degree programs.

Students’ Needs

Of twenty respondents from the questionnaire (see Appendix 1) in the first phase, sixteen were female and four males. Eighteen students were monolingual (Spanish speakers), while only two reported being bilingual (Spanish, English, and indigenous languages were considered). These students had spent an average of six years studying English, mostly in the public sector. However, most students reported their learning experiences as unsatisfactory. They said that the skills they needed to improve were listening, reading, and speaking. They also mentioned that some activities they preferred to learn the language were involving music, games, pictures, or conversations.

Nevertheless, students spent about two hours weekly on an independent study of the target language. These students also mentioned that they needed English mainly to read scientific articles, understand conferences, communicate in the language, travel, or teach. Even though only one of these students had a certification, 18 students were interested in obtaining a certification to determine their English level and the skills they needed to improve.

Faculty Needs

Another questionnaire for the interview with six faculty members (see Appendix 2) was also administered in the first phase and another interview with six faculty members was carried out in Spanish in this first phase (see Appendix 2 for the Spanish interview form). Most of them reported that the use of English in their profession was significant and frequently used the language during their studies. When they were asked about the main skills they needed to develop in English, four replied that it was reading. The material they had used in English during their studies were mainly scientific articles (the most useful), manuals, and books. These responses provided information about the resources needed to design the new curriculum.

Additionally, when asked about the tools or resources they used to understand English material, five reported they used bilingual dictionaries and translators. They indicated that the most useful activities during their English courses had been exercises, grammar rules, handouts, and student exchanges. They expressed their English classes had been interchange programs and that English courses had been taught throughout the whole degree program. Further, they voiced instructors should take on a facilitator role, and English should be used for their professional communication purposes. Finally, they wanted conversation clubs and videos to practice the language. The most difficult challenge for them when facing materials in English was grammatical structures, writing, and vocabulary.

Three of the six professors used English frequently in their professional field; two used it sometimes, and one said they always used it. When asked to identify situations in which they had used the language, their answers varied: Two professors reported they used it for research, another two for interacting with foreign people, one for training, and another for self-updating. In question 12 of the questionnaire, they were asked about which language skill they used most, once again, they said it was reading. Of the six participating faculty members, four mentioned that they asked students to read articles in English. The others mentioned they asked them to consult English-language information in books, videos, and PowerPoint presentations.

Furthermore, when asked about recommendations for students to make their English comprehension easier, a professor advised them to read scientific articles. Another professor went for checking PowerPoint presentations, a third one for reading ludic texts and listening to discussions or debates in English, and a fourth one for watching videos of English native speakers. Unfortunately, the remaining two did not suggest any strategy. These answers facilitated a better understanding of health sciences professionals’ perspectives regarding the students’ language learning needs.

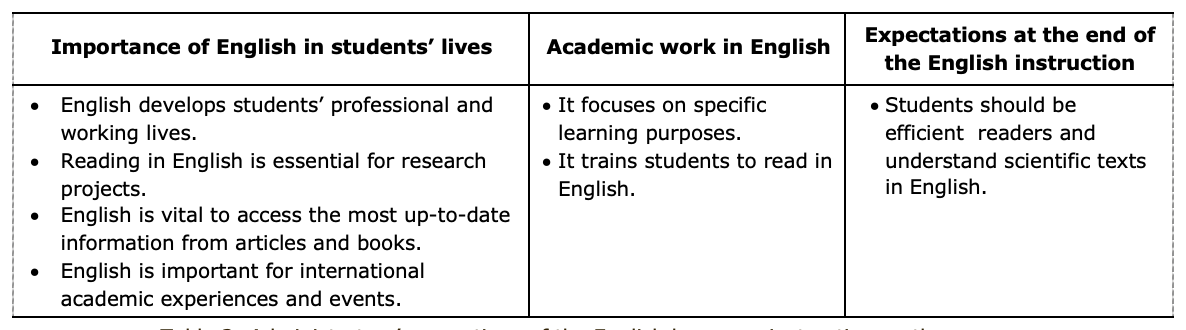

Administrators’ Needs

Four coordinators leading different programs the general administrator, and the campus director were also interviewed in Spanish to identify their perspectives on the importance of English-language instruction (see Appendix 3 for Spanish interview form). The results from these interviews are summarized in Table 3.

As described in the methodology of this study, the perspectives of these three groups (students, faculty members, and administrators) were matched to develop more specific criteria to select, adapt and adopt materials as well as to make collaborative agreements to implement adaptations in the analytical syllabi of the four levels (see the Table in Appendix 4).

Table 3: Administrators’ perceptions of the English language instruction on the campus

Table 3: Administrators’ perceptions of the English language instruction on the campus

Students’ Perceptions after Completing their EFL Classes

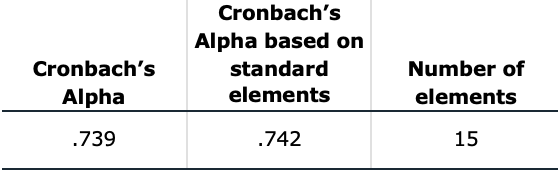

The internal validity of the questionnaire on student perceptions was assessed for Cronbach’s Alpha using SPSS version 24, indicating it was a relatively reliable instrument (see Appendixes 6 and 7). Of the 191 students that answered the questionnaire, most belonged to the Clinical Nutrition (23%), Nursing (22%), and Community and General Medicine (22%) degree programs; nevertheless, students from the degrees in Stomatology (14%), Psychology (11%) and Physiotherapy (9%) also participated. Tables 4 and 5 below show the global results of this survey’s statistical analysis that demonstrate the internal validity and reliability of the questions posed in the survey (see Appendix 7).

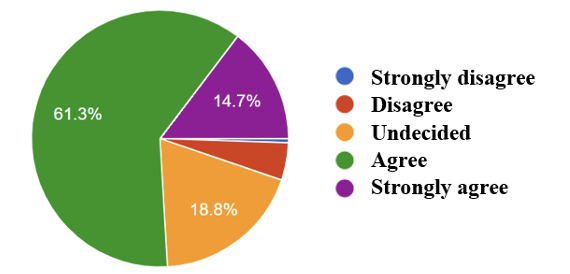

Table 4: Survey statistical reliability

Table 5: Survey scale

Results from the questionnaire administered online to the 2014 cohort revealed their perceptions of three topics: the use of tasks, a self-assessment of an A2 level in the four skills, and the use of the language in other subjects. The Figures that are presented below show only a couple of key findings from the survey. The survey statements (items) in the headings were translated from English to Spanish.

Students’ Perceptions of Using Tasks in their Language Classes

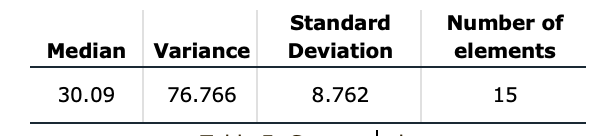

Of the students who took part in the study, 55% agreed that the objectives set for the tasks were clear, and 28% strongly agreed that the objectives were clear (see Figure 1). Thus, overall, 83% of the students considered the objects were clear to various extents.

Figure 1: Clarity of task objectives

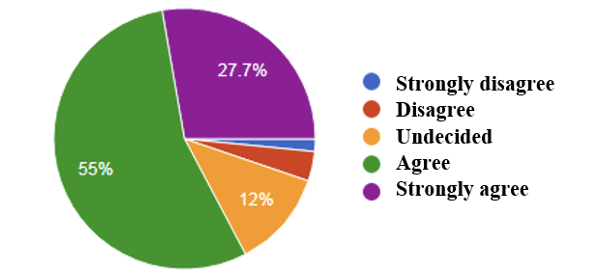

Of the students surveyed, 14% strongly agreed that their English competence increased, and 53% agreed that their English level increased (see Figure 2). More than half considered that their English level had increased after taking four courses based on TBLT, while only 6% considered that their level of English had not increased. This finding shows that more than half of the students’ population in this cohort using TBLT seemed to favor their English learning.

Figure 2: Tasks improved their competences in English

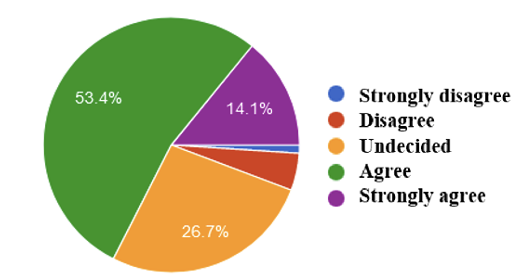

Figure 3 points out the importance of using TBLT within an appropriate environment that met the students’ context. With this item, the study aimed to find the perceived relationship between using tasks and how students perceived their learning during the courses.

Figure 3: Working with tasks promoted an appropriate learning environment

Overall, students had a positive perception of the methodology and topics used during the four language courses. According to the data collected, 76% of students reported that working with tasks provided a context suitable for learning the language; 19% were undecided on that issue, but only 5% answered negatively (see Figure 3).

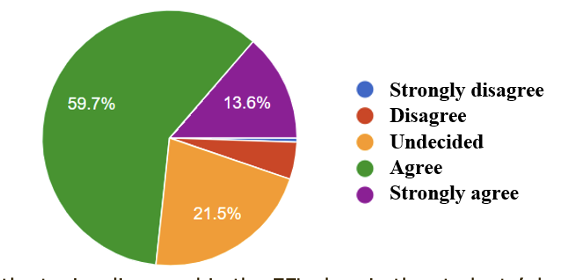

The Relevance of the EFL Class

The results showed ESP seemed to be meaningful for these students, not only in learning English but also for discussing topics related to their degree program. The majority reported relatively positive perceptions, with 60% agreed and 14% strongly agreed that the topics discussed in their EFL classes applied to their needs (see Figure 4).

Figure 4: Relevance of the topics discussed in the EFL class in the students’ degree program

Figure 4 shows that more than half of the surveyed students (60%) perceived that the topics discussed in the English classes were related to their degree program in English, which was one of the intended outcomes of the syllabus proposed.

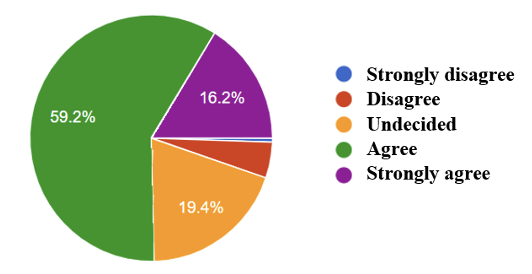

Finally, Figure 5 shows that most students viewed their learning of English as useful for other subjects in their degree programs. Fifty nine percent of the students agreed and 16% strongly agreed. All in all, the results above provide key evidence on how students felt about their four EFL classes and reinforce the idea that they were useful and meaningful in the students’ learning at university. Accordingly, it seemed that the materials and innovations in the analytical syllabi met the needs and wants of these students’ academic and professional contexts.

Figure 5: Usefulness of the EFL class for other subjects

Discussion

As a result of carrying out an initial needs analysis exploration (e.g., Fatihi, 2003; Hutchison & Water, 1987; Seedhouse, 1995) of this public university’s context, a group of English teachers implemented a couple of innovations in the four courses of the EFL programs by integrating TBLT within ESP. This study led to teachers’ compelling collaborative experiences while selecting, adapting, and creating materials to integrate them into an analytical syllabi. At the end of the four required English courses, students’ perceptions were assessed in a survey in which a positive outcome was obtained.

These results are in line with the conclusions of Willis (1996), Jarvis (2015), and Anwar and Arifani (2016) about the necessity of providing an appropriate context to support students’ capacities for recognizing their mistakes and correcting them; it is an essential element of TBLT to promote communication. Besides, tasks were meaningful learning vehicles to enhance productive skills, which had clear communicative objectives within the students’ academic contexts (Ellis, 2003; 2009).

However, there were several challenges across the three phases of this needs analysis exploration. Such challenges include:

- integrating students’ general needs into the analytical syllabus;

- adapting the contents to be taught within the participating students’ degree programs context;

- obtaining and adapting authentic materials to teach reading and listening;

- selecting suitable materials for each unit’s objectives;

- teaching large classes (from 25 to 45 students);

- investing extra time in planning, conducting, and assessing weekly tasks; and

- matching teachers’ different teaching and learning philosophies.

These limitations and other specific hardships were solved by the four English teachers in this study during the frequent meetings of the English Academy. This practice motivates rich discussions for problem-solving, as suggested by Luo and Garner (2017). Furthermore, adapting needs analysis instruments to assess students’ needs and expectations at the beginning of EFL courses is highly recommended. Having these factors and recommendations in mind could help teachers develop, adapt, or adopt more flexible and user-friendly syllabi that meet students’ language learning goals more realistically.

In light of the above, the methodological proposal using TBLT to support an ESP approach for language learning could be suggested for other EFL programs in public higher education to facilitate their language-learning process. Although it is crucial to recognize that each cohort’s context and the students’ characteristics should be considered when planning courses.

Conclusion

The results suggest EFL programs should be developed per the current students’ needs (Hutchinson & Waters, 1987) of the various areas of subject knowledge and study within a university context. Revising EFL programs in this way can help teachers respond better to students’ learning needs within their degree programs, which can improve their motivation to use English when discussing content-knowledge topics necessary for their academic and professional development. Thus, this study contributes to English teaching and learning in public higher education in Mexico and other EFL situations in the world (Criollo-Avendaño, 2010; Davies, 2008, 2020; González et al., 2004). It also adds to the reconceptualization of paradigms on internationalization, learning, and innovations in education and responds to the demands placed on language training in this rapidly changing and globalizing world (Crystal, 1997; Hyland, 2007).

References

Alsamadani, H. A. (2017). Needs Analysis in ESP Context: Saudi Engineering Students as a Case Study. Advances in Language and Literary Studies, 8(6), 58-68. https://doi.org/10.7575/aiac.alls.v.8n.6p.58

Anwar, K., & Arifani, Y. (2016). Task based language teaching: Development of CALL. International Education Studies, 9(6), 168-183. http://dx.doi.org/10.5539/ies.v9n6p168

Belcher, D. D. (2006). English for specific purposes: Teaching to perceived needs and imagined futures in worlds of work, study, and everyday life. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 133-156. https://doi.org/10.2307/40264514

Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. (2007). Modelo universitario minerva [Minerva university model]. Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. http://acreditacion.cs.buap.mx/docs/Carpeta4/Apendice4.1.6.1.pdf

Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla. (2013). Plan de desarrollo institucional 2013-2017 [Institutional development plan 2013-2017]. http://cmas.siu.buap.mx/portal_pprd/work/sites/contraloria/resources/PDFContent/444/PDI_2013-2017.pdf

Carkin, S. (2005). English for academic purposes. In E. Hinkel (Ed.), Handbook of research in second language teaching and learning,(pp.85-98). Lawrence Erlbaum.

Chamot, A. (2007). Accelerating academic achievement of English language learners: A synthesis of five evaluations of the CALLA Model. In J. Cummins & C. Davison (Eds.), International handbook of English language teaching, (pp. 317-331). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-46301-8_23

Córdoba Zúñiga, E. (2016). Implementing task-based language teaching to integrate language skills in an EFL program at a Colombian university. PROFILE Issues in Teachers’ Professional Development, 18(2), 13-27. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v18n2.49754

Council of Europe. (2018). Common European framework of reference for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment: Companion volume with new descriptors. https://rm.coe.int/cefr-companion-volume-with-new-descriptors-2018/1680787989

Creswell, J. W. (1999). Mixed-method research: Introduction and application. In G. J. Cizek (Ed.), Handbook of educational policy (pp. 455-472). Academic Press. https://doi.org/10.1016/B978-012174698-8/50045-X

Criollo-Avendaño, R. (2010). Política institucional de lenguas extranjeras de la BUAP [Institutional policy of foreign languages at the Meritorious Autonomous University of Puebla]. http://www.ingenieria.buap.mx/portal_pprd/work/sites/Vicerrectoria_docencia/resources/PDFContent/670/Politica-Institucional-Lengua%20Extranjera-BUAP.pdf

Cowling, J. D. (2007). Needs analysis: Planning a syllabus for a series of intensive workplace courses at a leading Japanese company. English for Specific Purposes, 26(4), 426-442. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2006.10.003

Crystal, D. (1997). English as a global language. Cambridge University Press.

Davies, P. (2008). ELT in Mexican higher education should be mainly ESP, not EGP. MEXTESOL Journal, 32(1), 79-92. http://mextesol.net/journal/public/files/4ef39a52b408374b2a829c0a46a96214.pdf

Davies, P. (2020). ¿Qué sabemos, no sabemos, y necesitamos saber sobre la enseñanza del inglés in México? [What do we know, do not know, and need to know about ELT in Mexico?] Revista Lengua y Cultura, 1(2), 7-12. https://doi.org/10.29057/lc.v1i2.5471

Dudley-Evans, T. & St John, M. J. (1998). Developments in English for specific purposes: A multidisciplinary approach. Cambridge University Press.

Ellis, R. (2003). Task-based language learning and teaching. Oxford University Press.

Ellis, R. (2009). Task-based language teaching: Sorting out the misunderstandings. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 19(3),221-246. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.2009.00231.x

Ellis, R. (2013). Task-based language teaching: Responding to the critics. University of Sydney Paper in TESOL, 8, 1-27. https://faculty.edfac.usyd.edu.au/projects/usp_in_tesol/pdf/volume08/Article01.pdf

Fatihi, A. R. (2003). The role of needs analysis in ESL program design. South Asian Language Review, 13(01), 39-59. http://www.geocities.ws/southasianlanguagereview/SecondLanguage/fatihi.pdf

González Robles, R. O., Vivaldo Lima, J., & Castillo Morales, A. (2004). Competencia lingüística en inglés de estudiantes de primer ingreso a instituciones de educación superior del área Metropolitana de la Ciudad de México [English proficiency of first-time students to higher education institutions in the Metropolitan area of ​​Mexico City]. Universidad Autónoma Metropolitana.

Hutchinson, T., & Waters, A. (1987). English for specific purposes: A learning-centered approach. Cambridge University Press.

Hyland, K. (2007). English for specific purposes: Some influences and impacts. In J. Cummins & C. Davison. (Eds.), International handbook of English language teaching (pp. 391-402). https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-46301-8_28

Jarvis, H. (2015). From PPP and CALL/MALL to a praxis of task-based teaching and mobile assisted language use. TESL-EJ, 19(1), 1-9. http://tesl-ej.org/pdf/ej73/a1.pdf

Johns, A. M., & Salmani Nodoushan, M. A. (2015). English for specific purposes: The state of the art (an online interview with Ann M. Johns). International Journal of Language Studies, 9(2), 113-120. https://drive.google.com/file/d/1qKkGDgvs0WkUYj5aXIM0p-4DDzorbXfn/view?usp=sharing

Long, M. (2014). Second language acquisition and task-based language teaching. Wiley Blackwell.

Luo, J., & Garner, M. (2017). The challenges and opportunities for English teachers in teaching ESP in China. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 8(1), 81-86. http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/jltr.0801.10

Otilia, S. M. (2015). Needs analysis in English for specific purposes. Annals of The Constantin Brancusi University of Targu Jiu, Economy Series, 1(2), 54-55. http://www.utgjiu.ro/revista/ec/pdf/2015-01.Volumul%202/08_Simion.pdf

Muller T. (2005). Adding tasks to textbooks for beginner learners. In C. Edwards & J. Willis (Eds), Teachers exploring tasks in English language teaching (pp. 69-77). Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9780230522961_7

O’Connell, S. P. (2015). A task-based language teaching approach to the police traffic stop. TESL Canada Journal, 31(8), 116. https://doi.org/10.18806/tesl.v31i0.1189

Paltridge, B., & Starfield, S. (Eds.). (2014). The handbook of English for specific purposes. John Wiley & Sons.

Ramirez Gómez, L. A., Pérez Maya, C. J., Lara Villanueva, R. S. (2017). Panorama del sistema educativo mexicano en la enseñanza del idioma inglés como segunda lengua [Overview of the Mexican educational system in the teaching of English as a second language]. Revista de Cooperación, 12, 15-21. https://revistadecooperacion.com/numero12/012-02.pdf

Rubin, J. (2015). Using goal setting and task analysis to enhance task-based language learning and teaching. Dimension, 70-82. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1080303.pdf

Seedhouse, P. (1995). Needs analysis and the general English classroom. ELT Journal, 49(1), 59-65. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/49.1.59

Secretaria de Educación Púbica. (2017). Aprendizajes clave para la educación integral. Lengua extranjera: Inglés: Educación básica [Key learnings for holistic education. Foreign language: English: Primary].https://www.aprendizajesclave.sep.gob.mx/descargables/biblioteca/basica-ingles/1LpM-Ingles_Digital.pdf

Skehan, P. (1998). Task-Based instruction. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 18, 268 -286. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190500003585

Strevens, P. (1988). The learner and the teacher of ESP. In D. Chamberlain & R. J. Baumgardner (Eds.), ESP in the classroom: Practice and evaluation, (pp. 39-44). Modern English.

Taillefer, G. F. (2007). The professional language needs of economics graduates: Assessment and perspectives in the French context. English for Specific Purposes, 26(2), 135-155. http://dx.doi.org/10.1016/j.esp.2006.06.003

Taylor-Powell, E. (1998). Questionnaire design: Asking questions with a purpose. University of Wisconsin-Extension.

Watanabe, Y. (2006). A need analysis for a Japanese high school EFL general education curriculum. SLP Papers, 25(1), 83-163. http://hdl.handle.net/10125/40685

Widodo, H. P. (2016). Teaching English for specific purposes (ESP): English for vocational purposes (EVP). In W. A. Renandya, & H. P. Widodo (Eds.), English language teaching today: Linking theory and practice (Vol 5, pp. 277-291). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-3-319-38834-2_19

Willis, J. (1996). A framework for task-based learning. Longman.

[1] The BUAP’s academic model integrated by educational principles, curricular structure, social impact, research and administrative descriptors.