In language learning, vocabulary is a common area of struggle as the increasing number of new vocabulary terms is often difficult to acquire at the needed rate. Additionally, vocabulary acquisition is crucial for effective communication and higher proficiency levels. As Wilkins (1972) stated “without grammar, little can be conveyed, without vocabulary, nothing can be conveyed” (pp. 111-112). After a long period of neglect and a focus on grammar in the English language classroom, vocabulary teaching and learning have recently come into the spotlight in English language teaching (ELT) gaining the focus they deserve for effective learner vocabulary development. However, learning vocabulary is not an easy undertaking, as the number of needed, high frequency vocabulary items at each proficiency level is broad and their usage is often complex with different meanings and collocational use. Initial word knowledge consists of knowing the form and meaning, and it gradually expands to other linguistic and semantic aspects, emcompassing the categories of meaning, form and use (Nation, 2005). Nevertheless, Barclay and Schmitt (2019) considered that all the possible aspects of word knowledge is something to aspire to but is not something that should or needs to be required, as not knowledge known, even native speakers have full knowledge of all the words in their language and complete knowledge of their use. What is true, though, is that “the more aspects of word the more likely it is that it will be used in the right contexts in an appropriate manner” (Barclay & Schmitt, p. 803), so special emphasis should be placed on the incremental nature of learning vocabulary. The most recent view of vocabulary is that it consists of all the words that exist in a language, whether they are single items or lexical chunks that carry a specific meaning just like individual word tokens do (Lessard-Clouston, 2013; Ur, 2012). However, each person knows and uses only a proportion of the total number of the words of a language, which are organized in what is known as the mental lexicon, and which includes all the different aspects of word knowledge (Caroll, 1999). Its development is a dynamic process, and the use of vocabulary learning strategies (VLSs) is instrumental in aiding this process and in making vocabulary acquisition more efficient.

Vocabulary Learning Strategies

Learning a language is a long, complex, and gradual process “by which information about the language is obtained, stored, retrieved and used” (Rubin, 1987, as cited in Easterbrook, 2013). To achieve this goal, learners make use of language learning strategies (LLSs), which are defined by Oxford (1990, p.18) as “specific actions, behaviours, steps, or techniques that students often intentionally use to improve their progress in developing second language (L2) skills and proficiency. These strategies can facilitate the internalization, storage, retrieval and use of the new language”. Cohen (2011, p. 7) considers LLSs to be “thoughts and actions, consciously chosen and operationalized by language learners, to assist them in carrying out a multiplicity of tasks from the very onset of learning to the most advanced levels of target-language (TL) performance”. Similarly, Griffith and Cansiz (2015, p. 476) suggest the following definition: “actions chosen (either deliberately or automatically) for the purpose of learning and regulating the learning of language”. Despite some differences among the definitions (mental activities vs actions, conscious vs automatic behaviours), the common ground is that LLSs are useful aids for learners to make their language learning more effective. Based on the definitions cited above, the view adopted in this article is that LLSs (with VLSs as a subcategory of them) are actions or mental processes that learners use actively in order to assist their own learning and take control of it.

Drawing on previous work on categorizing LLSs by Oxford (1990) and considering other existing classifications, Schmitt (1997) developed a comprehensive taxonomy of VLSs. These were divided into two major groups: discovery strategies, which are used to discover a word’s meaning, and consolidation strategies, used to consolidate a word when it is encountered again. In turn, discovery strategies were divided into determination strategies (used by learners to discover the meaning of a new word on their own, by using a dictionary, context clues or structural knowledge of the word) and social strategies (when learners ask someone who knows for the meaning). As for consolidation strategies, learners make use of social strategies (such as practising the meaning of new words in a group), cognitive strategies (that include repetition and mechanical methods such as using word lists and flashcards to study vocabulary), memory strategies (that involve linking the word to be learnt with existing knowledge using imagery or grouping) and metacognitive strategies (which include planning, monitoring and evaluation of learning).

Teachers should also provide students with opportunities for repeated encounters of words in various contexts (Webb &Nation, 2017), and train them to use effective VLSs strategies (Alqahtani, 2015), as these pedagogical actions contribute to improving students’ vocabulary competence. In this way, learners can have an active and independent contribution to the development of their vocabulary not only inside, but also outside the classroom, regardless of the amount and quality of the direct vocabulary instruction they experience in the English language classroom.

The use of strategies depends on several factors in the learning context such as the teacher, learners, classroom, family support, and social and cultural traditions (Gu, 2003). The language proficiency and maturity of the learner have an important role to play. Generally, shallower strategies are used by younger learners or beginners, and deeper strategies are used by more cognitively mature learners or with higher levels of proficiency (Cohen & Aphek, 1981). There is not a one-size-fits-all strategy, or combination of strategies, that can be identified as the most effective. Instead, each learner has to adopt the strategies that fit their learning context and needs. However, it is the teacher’s duty to leave behind traditional methods of teaching vocabulary that are still commonly used in many EFL settings around the world and in which “the teacher is the sole authority and the source of all knowledge and learners are the passive recipients” (Ali & Zaki, 2019, p. 2). Teachers need to adopt a distinct role, where they serve as a coach that provides training in VLSs and allows students to take control of their own vocabulary learning. In addition, as Nation (2008) points out, learners can benefit more from learning VLSs to deal with low frequency words than from being explicitly taught them in the classroom.

The research questions the present study sought to address were:

- What strategies do students at the Chapingo Agricultural High School use to learn vocabulary?

- What is the frequency of use of these strategies?

Methodology

Participants

One hundred and seven students in their final year of high school took part in the study. They were both male and female, ranging from 17 to 20 years of age. They belonged to five different English groups, so convenience sampling was used. The research was carried out in 2017 at the Agricultural High School of the Universidad Autónoma Chapingo in Texcoco, Mexico. The school is a boarding school with students living in on-campus dormitories or nearby rental accomodation. The high school receives an extremely heterogeneous population of students from different urban or rural areas of Mexico, some of whom have never received any English instruction, while others possess an official certificate of English language course completion. The English program consists of four levels, each one with a duration of one semester, for students in second and third grade. Although a high proportion of students are not true but false beginners, the program design caters for those who have never taken English classes before entering high school. It is expected that at the end of the instructional period of the four levels students are expected to reach Level A2 on the CEFRL (Council of Europe, 2001).

Research instrument

This research was based on a descriptive survey with the aim to create a picture of VLSs used by the 107 student participants. Quantitative methods have been commonly used in studies on VLSs in different parts of the world, as evidenced in a recent review by Ali and Zaki (2019). A 5-point Likert-type questionnaire (5=always, 4=often, 3=sometimes, 2=rarely, 1=never) was used as the instrument for data collection. The questionnaire was a modified version from the one used by Easterbrook (2013), and it was chosen as a model because it contains a very comprehensive list of VLSs. It consisted of 54 questions divided into 7 Sections. The purpose of Sections 1, 3, 4, 5, 6 and 7, comprised of 51 questions, was to obtain information about the strategies students use and their frequency of use, while Section 2 contained three questions about the place where students attend to learning their English vocabulary. Details about the VLSs category, the question heading each VLSs category in the questionnaire, the number of ítems in each category, and the acronyms that will be used hereafter are given in Table 1 below.

Table 1: Categories of VLSs included in the questionnaire

The VLSs category names acknowledge Schmitt’s (1997) classification, and “have been expanded to highlight their function and goal” (Easterbrook, 2013, p. 25). Although Easterbrook’s study included two other categories (i.e., Consolidation: Remember and Consolidation: Production categories) these were not included in the present investigation due to the level of student profiency and their limited opportunities to practise in social interaction outside of class. Other modifications intending to adapt the original questionnaire to the context of the study’s participants are as follows: i) Questions 5a and 6k were modified compared to the original questions for the participants’ context; ii) Questions 3h, 6s, 6r, 6p, and all the questions in Section 7 were new, not present in Easterbrook’s VLS questionnaire, to inquire about specific details of the participants; iii) three questions from the original questionnaire belonging to Sections 3, 5 and 6 were excluded, as they were not deemed relevant to the study. Finally, Section 2, which did not contain VLSs, was headed by the question Where do you often learn English vocabulary?

The questionnaire was administered in Spanish class during the instructional period. As participants belonged to different class sections (i.e., Groups), it was not possible for the researcher to be present at the time all the questionnaires were administered, and therefore requested the participation of two colleagues to assist in administering the questionnaire. Prior to this, the colleagues were briefed on the nature of the study and the purpose of the survey. All students were in turn informed by the respective teacher (i.e., survey proctor) about the purpose of the investigation, about the nature of the procedure for responding to the questionnaire, and to request clarification of any questions they might have had. All of the participants agreed to answer the questionnaire, with their participation as anonymous. The only personal information required was their age. Although there were some incomplete questionnaires, reflected in the variable with n in the Results Section, none of them was invalidated, as they did not contain more than three unanswered questions, which was the indentified limit to invalidate a participant’s questionnaire responses.

Data analysis

The quantitative data was compiled using Excel sheets, and analysed using the following descriptive statistics: The percentage of use of each strategy corresponding to each frequency, and the mean and the standard deviation for each strategy. The non-parametric tests means and standard deviations were included to aid the percentage analysis and were chosen due to an ordinal data type produced based on the Likert-type questionnaire.

Results and discussion

The mean values shown in Table 2 for each category of strategies indicate their use at a medium level, except for the category of CON-ORG, whose mean signals a low use. A mean value of 1.00 to 2.49 represents low use, 2.50 to 3.49 medium use, and 3.50 to 5.00 frequent use (Wahyuni, 2013). Three main factors can account for these results. They are, namely the lack of training on the use of VLSs (and therefore unwareness of them), the lack of practice due to the limited schedule time for English (only three hours a week of English instructional time) and the culture of learning in the context of the institution and/or of the country (i.e., Mexico).

Table 2: Mean values for each category of VLSs

The means for each category of VLSs to individual strategies, out of the 51 VLSs included in the questionnaire, showed 13 strategy types reflected frequent use, 21 strategy types, medium use, and 17 strategy types, low use.

High-use strategies

Table 3 presents the 13 high-use strategies, which are spread across the categories of DIS-PLA (4 strategies), DET-IRE (3 strategies), DET-STU (3 strategies), CON-ORG (1 strategy), CON-MEM (1 strategy) and CON-REV (1 strategy).

Table 3: Strategies of frequent use

Four of the most used strategies were of DIS-PLA type. Forty-nine percent of the participants found new words in songs, movies, or programs in English effective as a learning strategy. Other material identified that served as a source of new words was books and magazines, the textbook and classroom activities, and the internet with 36.4%, 47.7 and 32.7% of the students, respectively, indicating they often or always encountered new words as part of their study. Spoken and written input proved to have potential for incidental vocabulary learning (de Vos et al., 2018; Krashen, 1989). Exposure to spoken and written language also helps develop deeper features of word knowledge, such as collocations, derivation, polysemy, and register (Barclay & Schmitt, 2019). The results showed that apart from the textobook and classroom activities, students were exposed to other sources of vocabulary, represented in books and media, which served beneficial for their learning.

Six of the high-use strategies belonged to the determination type. Three of them had to do with predicting the meaning of the words (DET-IRE), and the other three involved lexical aspects students studied about the words (DET-STU). The DET-IRE strategies were represented by looking for the meaning of the words on a translator, always used by 42.1% of the participants, asking a classmate or the teacher for the meaning, a social strategy often employed by 40.2% of the students, and guessing the meaning of the word using context clues, often used by 33% of the surveyed students. Due to their immediate availability, digital and online translators exceded use of the traditional print-based dictionary. In other studies carried out by Schmitt (1997) in Japan, and Fan (2003) in Hong Kong, the use of a dictionary was found to be among the most used strategies, while in the present study, only 3.7% of the participants reported always using it. The difference might be because at the time the studies mentioned were carried out, online translators did not exist or they were still in their infancy. Since 2012, when Google Translate was launched (unitedtranslations, 2018), machine translators have become more popular and currently they are very advantageous for language learners. In a study carried out with undergraduate students in Kurdistan, Askar (2015) found that social strategies were among the least used strategies, indicating that vocabulary learning was considered an individual activity. In contrast, this was one of the preferred strategies by the respondents in the present investigation, probably reflecting the open nature and sociocultural beliefs of Mexican students. The slightly lower use of guessing word meaning from context compared to translators and asking the teacher or a classmate for a word meaning can be attributed to the low proficiency level of the respondents. Although this strategy has been widely encouraged and found to be a common practice in the English classroom as revealed in a review study of VLSs by Ali and Zaki (2019), its optimal use depends on “ironically … a large vocabulary” (Folse, 2004).

As for the DET-STU strategies, 40.2%, 39.3% and 30.5% of the surveyed students often studied the pronounciation of the words, their meaning in Spanish and their spelling, respectively. The spoken and the written form of words, and their meaning, are the basic aspects of word knowledge that provide a starting point for learning (Schmitt, 2007). Therefore, these percentages could be partially seen as low with respect to VLSs.

Only three of the high-use strategies were consolidation strategies, represented by studying before an exam or evaluation (CON-STU), repeating words aloud several times to memorize them (CON-MEM), and taking notes in class (CON-ORG). Around forty percent of the participants reported always studying before an exam or test. Between 31% and 43% of them reported never or hardly ever reviewing vocabulary if it was not the focus for an evaluation (see low use strategies section). This is not an encouraging finding, as without review, vocabulary is likely to be forgotten if teachers do not create opportunities to recycle partially known words, apart from presenting new words (Webb & Nation, 2017). The data suggest that instrumental motivation, such as obtaining a good grade, is one of the strongest factors that drives students to study vocabulary. Amirian and Heshmatifar (2013) cited various experiments in which oral and written repetition of the words to learn was among the most used strategies. In the present study, repeating words aloud several times ranked 11th among the most used strategies, being used often by 33.6% of the surveyed students. Although the repetition technique has been called into question, it can actually be quite efficient if learners are used to it (O’Malley & Chamot, 1990, as cited in Schmitt, 1997), as shallow techniques are frequently used by beginners. The third frequent-use consolidation strategy was represented by taking notes in class, which addresses organizing information about new words to make it available for review in the near future, such as when preparing for a quiz or an exam. In this study, it was frequent strategy used by 37% of the participants.

Similarly to the present study, in a review of 14 studies on VLSs carried out in different countries, Ali and Zaki (2019) reported that in nine of them, determination strategies were preferred by learners, which suggested a tendency towards traditional methods of vocabulary learning. Although these strategies allow students to know the meanings of unfamiliar words, this does not necessarily lead to learning with respect to use and language proficiency. Long-term retention and converting passive vocabulary into active vocabulary is facilitated by consolidation strategies and active word use. The results showed that the surveyed students did not frequently make use of effective strategies for consolidating words into their working memory.

Medium-used strategies

Table 4 presents the 21 strategies of medium use, which span the categories of DIS-PLA (3 strategies), DET-IRE (2 strategies), DET-STU (4 strategies), and CON-MEM (12 strategies).

Table 4: Strategies of medium use

Three medium-use strategies pertained to sources of new words. A little over 26% of the students rarely found new words in conversations with others, which was not surprising, as they learn English in an EFL context with limited opportunities to practice English outside the classroom. However, about 35% of the students indicated that they sometimes found unknown vocabulary items in vocabulary lists ordered alphabetically or according to their meaning (thematic or lexical lists), which could be provided by teachers or found in textbooks.

Two strategies were part of the DET-IRE category. Looking up a word in a bilingual dictionary was reported to be used sometimes by 27.1% of the respondents. As seen earlier in the high-use strategies section, using an online translator or digital dictionary is preferred opposed to a print dictionnary. Nonetheless, the possibility of an online bilingual dictionary being reported as a translator cannot be discarded. The results for the other DET-IRE strategy showed that 38.3% of the participants sometimes did not pay attention to a new word but went back to it later to identify its meaning. This indicates that unknown words, initially ovelooked, were given attention later by the participants.

Among the medium-used strategies, four of them were DET-STU. Almost 33% of the participants sometimes studied the meaning of the words in English and the word’s relationship with other words. The latter aspect is extremely important, as apart from learning individual words, learners should also learn collocations, as they make the oral and written discourse sound more natural. Examples sentences were often studied by 28% of the respondents, and the part of speech sometimes studied by 31.8% of them. Example sentences provide a context for the new words, and knowing the part of speech of the words is important in order to use them correctly.

Finally, in this group there were 12 CON-MEM strategies. Three of them offer significant findings: i) looking at the words several times was used often by 33.6% of the participants, ii) writing the words several times was employed sometimes by 26.2% of them, iii) memorizing words lists using cognitive strategies that involve mechanical repetition was noted by 24.3%. Students also reported using deep strategies. They are as follows: relating new words to words they already knew that have lexical parts in common (31.8%, sometimes), relating the words to synonyms (26.2%, often), connecting the words with their experience (21.5%, sometimes), making a phrase or sentence using the words (29.9%, sometimes), and making a mental image of the words (29.0% sometimes). Although used at medium level among the participants, memory strategies, or mnemonics, have proven to be more effective than memorization strategies, as they involve deep semantic processing of the words (Oxford, 1990).

One memory strategy of medium use was studying and practising words with a partner, used sometimes by 27.1% of the participants. Universidad Autónoma Chapingo is a boarding school, where students often share a room with others, and therefore the social strategy of studying and practicing with a partner is likely to take place. However, based on being an EFL context, the students encounter few to no opportunities for natural use and interaction in the language.

In recent years, there has been a dramatic increase in the number of apps for learning English on portable devices, especially cellphones. However, only 24.3% of the surveyed learners reported that they sometimes use a cellphone app for learning vocabulary, which suggests the appealing opportunities for interactive and personalized learning that apps provide are largely overlooked.

Low use strategies

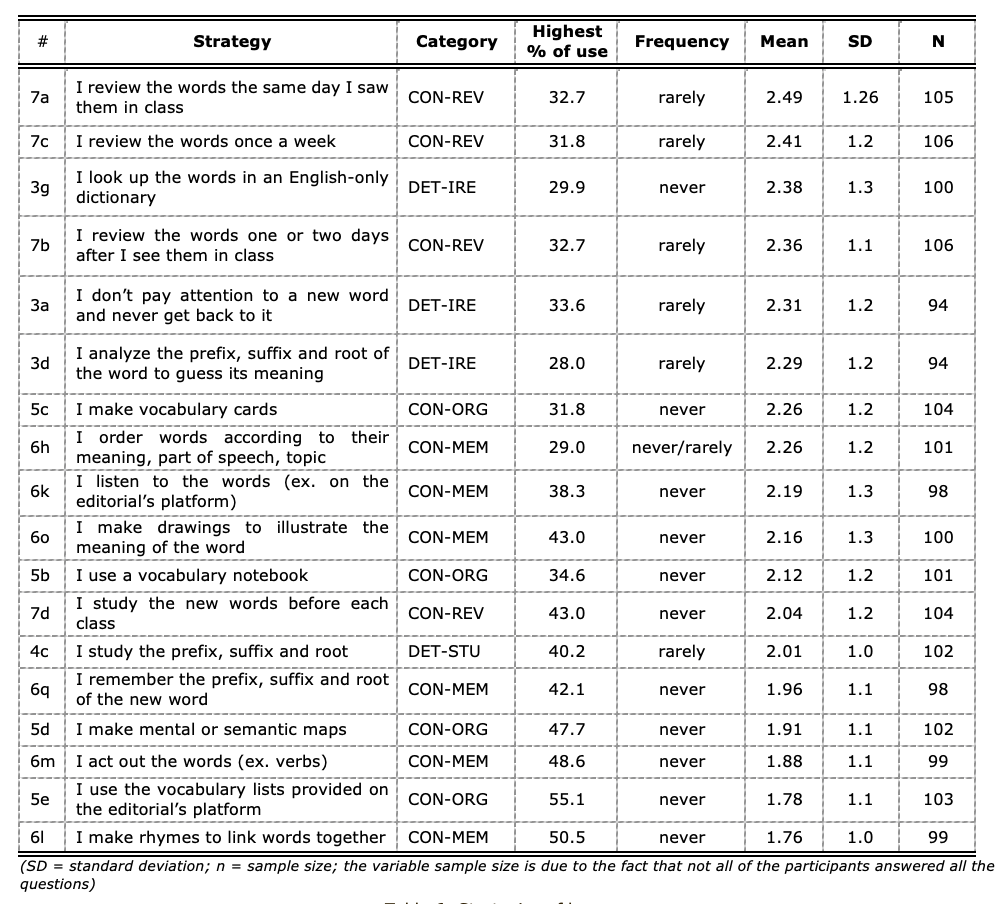

The low use strategies were related to the following categories: DET-IRE (three strategies), DET-STU (one strategy), CON-ORG (three strategies), CON-MEM (six strategies) and CON-REV (four strategies).

Table 5: Strategies of low use

Three of the least used strategies were of DET-IRE type. Considering the fact that participants were learners of an elementary level, looking up words in a monoligual dictionary, a strategy that 29.9% of them never resorted to, is not surprising, as understanding definitions in this kind of dictionary requires a certain level of vocabulary. As discussed in previous sections, other techniques for determining word meaning were better rated. When encountering new words, learners have the option of not paying attention to them, and never going back to them, which was reported by 33.6% of the surveyed learners as an approach rarely used. Although not shown in the table, the vast majority of the answers to this question clustered in the never, rarely and sometimes range, which means that learners would not ignore the words, but would actually get back to them. This indicated a proactive attitude towards determining the meaning of unknown words found in different sources.

The third DET-IRE strategy, which was analyzing the prefix, suffix and root to determine a word´s meaning, was rarely used by 28% of the participants. This can be explained by the fact that at lower levels students are not fully aware of the wide variety of prefixes, suffixes and stems that can be used to identify the meaning of unfamiliar words. Two other low use strategies, which involve studying (DET-STU) and remembering (CON-MEM) the prefix, suffix and root, were rarely used by 40.2% and never by 42.1% of the participants, respectively. Knowledge of word parts, namely affixes and stems, facilitates predicting and learning the meanings of the words containing them, as “about 60% of the English vocabulary comes from French, Latin or Greek” (Webb & Nation, 2017, p. 117). In addition, the word parts technique, in which the meanings of word parts are used to identify the meaning of the complete word, is very useful for remembering words (Webb & Nation, 2017).

The following CON-ORG strategies were reported as never being used by 31.8% (making vocabulary cards), 34.6% (using a vocabulary notebook), 47.7% (making mental or semantic maps) and 55.1% (using the vocabulary lists provided on the editorial’s platform) of the surveyed learners. This indicates that a great number of students did not dedicate any time out of the classroom to reorganizing vocabulary on their own, probably due to lack of time, or lack of awareness or knowledge of the benefts these strategies can provide. Baleghizadeh and Ashoori (2011) cited two studies that indicated flashcards had a positive effect on language learning, despite the fact that they have been the target of criticism for encouraging memorization. They are especially useful for learning basic aspects of word knowledge, such as the form-meaning link (Barclay & Schmitt, 2019). Keeping a vocabulary notebook was considered by Vela and Rushidi (2016) an effective tool that motivates students to learn, as it contributes to sharing power with them and supports their autonomy. Of course, for a vocabulary notebook to work, regularly using it to write in new words and other aspects of vocabulary to be learned is not enough; it has to go hand in hand with regular review and/or vocabulary exercises. According to Webb and Nation (2017), making mental or semantic maps to organize vocabulary works best if done under the teacher’s guidance, as their creation involves combining teacher’s and students’ knowledge. They are very useful to increase the recall of words (Nattinger, 1988, as cited in Farjami & Aidinlou, 2013). The vocabulary lists available on the platform that complemented the participants’ textbook contained the meaning of vocabulary items in English, an example sentence and pronounciation. In addition, the platform facilitated the students’ recording themselves and comparing their pronunciation to a model sample. However, more than half of the students indicated they never made use of these resources. Informal comments from students indicated that some of them only worked on the platform on a few occasions when they were taken to the lab, but not during their own study time. List learning or learning word pairs allow learners to make quick progress in acquiring words (Schmitt, 1995) and is commonly used in the English classroom (Baleghizadeh & Ashoori, 2012), in spite of being disapproved on the grounds of not promoting meaningful learning. Therefore, such online tools accompanied with the textbook may facilitate learner acquisition, as some of these features are/maybe be present.

The six CON-MEM strategies of low use were never employed by between 29% and 50.5% of the participants. These strategies were: i) ordering words according to their meaning, topic or part of speech, ii) listening to the words, iii) making drawings of the words, iv) remembering the prefix, suffix and root (already discussed above), v) acting out the words and making rhymes. Except for listening to the words, which is a cognitive strategy that involves repetition, the other five are memory strategies. Schmitt (1997) found that the type of strategies learners use depends on their language level, with beginner students using shallow strategies and more advanced students employing deeper learning startegies. Remembering the prefix, suffix and root falls into the category of strategies that require a greater cognitive effort, apart from knowledge of the meanings of prefixes, suffixes or roots, is important to bear in mind when considering the level of the learner and strategies used. However, making drawings, which “make mental images more concrete” (Zahedi & Abdi, 2012, p. 2266) or acting out the words are suitable for lower levels, and students could benefit from using them.

Finally, four CON-REV strategies fell within the group of low use. About 32% of the surveyed learners rarely reviewed vocabulary the same day they saw it in class, once a week, or one or two days after seeing it in class. Forty-three percent of them never studied it before each class. Reviewing is a metacognitive strategy and this strategy appeared to not be utilized by a high proportion of the participants, probably because of lack of time or unawareness of the advantages it has for learning English vocabulary. Without regular review, vocabulary is likely to be forgotten. Webb and Nation (2017) suggested that a number of 5-16 encounters with a word is necessary for it to be acquired. In addition, a large amount of evidence has proven that spaced repletion learning is better for long-term retention than massed one time event learning (Webb & Nation, 2013). Repetition is essential for learning, and encountering words in new contexts is particularly important, as apart from consolidating previous word knowledge, it enriches it with new aspects (Nation, 1990, as cited in Barclay & Schmitt, 2019).

Results for Section 2

Table 6 shows the figures for Section 2 of the questionnaire, which did not include VLSs, but dealt with the physical location where participants often learned vocabulary, such as the classroom, the library and their (dormitory) room. As mentioned earlier, the Agricultural High School of the Universidad Autónoma Chapingo is a boarding school, where the majority of the students live on the campus or in rented accomodation around it.

Table 6: Physical places where the surveyed learners often learned vocabulary

The results revealed that the surveyed students did learn vocabulary in these three places, and no extra location was mentioned by any of them, although the questionnaire contained an open-ended option where the participants could write in other sites where they learned vocabulary. The classroom was found to be the place where most of the learning occurs, followed by their rooms. The fact that the library was the site where students least learned vocabulary may be explained by the extremely demanding academic schedule, which does not allow them much time for studying in the library.

Implications and Conclusion

The purpose of this investigation was to determine which VLSs the surveyed students tended to use, as well as their frequency of use. The results showed that the surveyed learners overall are medium users of VLSs. It was identified that determination strategies were among the most frequently used strategies. Memory strategies were among the second most utilized (i.e., medium use level). Strategies involving student personal independent and autonomous action were among the least utilized (i.e., low use level). In summary, the data indicate that the participants took action to become familiar with the meanings of the words but did not make sufficient use of memory strategies to consolidate this initial knowledge within short term memory to move it into the long term memory to make it available for future use. Whether the medium level of use of VLSs was due to the influence of the cultural beliefs, the learning experience or lack of training, is not known, and it was not the purpose of this research to examine this issue. However, the results provide an indication as to which strategies may be most useful for teachers to present in the classroom in order to train students to practice such strategies regularly in and out of class. The goal is that they become part of the students’ repertoire of incorporating them into their study approaches independently outside of the classroom. For example, organizing and memory consolidation strategies that are suitable for beginner and elementary levels and that turned out to be of medium use (such as connecting the words with their experience and making mental images), or low use, (such as keeping a lexical notebook, making drawings and reviewing regularly) have a great potential for learning vocabulary. Since there are different strategies available and each strategy may be more or less suitable for a particular proficiency level, students will need guidance on which strategies may be most suitable. Additionally, as students progress from one proficicent level to the next what they used previously may no longer be the most effective and will need guidance on revising and adapting their VLSs.

With the shift from teacher-centered to learner-centered learning, there is a great emphasis on independent learning, and using VLSs provides a means to improve vocabulary outside the classroom (Webb & Nation, 2017). Apart from learning strategies, learners should also be taught about how to apply the most suitable strategies depending on the learning situation, in other words to explicitly instruct learners on metacognitive strategies (Rasekh & Ranjbary, 2003). According to Nation (2013), teachers have four roles: planning the course, training learners in language learning strategies, testing and teaching. This hierarchy of roles reveals the importance of strategy training compared to direct instruction, and of providing learners with the tools they need to make their way easier along the challenging but rewarding path of vocabulary learning.

Although VLs has been well examined in the field, the present study contributes to enriching the understanding of VLSs use among elementary learners of English. With respect to the Mexican ELT context, it offers further insight as only a few studies have been carried out up to date in this area of language learning (Bermejo del Villar et al., 2016; Hernández-Cueto et al., 2016; Marin-Marin, 2005). Nonetheless, the study has some limitations. First, the results cannot be generalized due to the sample size; nevertheless, as stated it still offers a glimpse into the actions that students take to deal with vocabulary learning. Secondly, the questionnaire only included a few questions related to metacognitive strategies, which nowadays is gaining more and more ground as a field of inquiry and relevance regarding VLSs. Therefore, a future study with a focus on investigating the use of metacognitive strategies by means of a qualitative approach would be useful to complement the general view on VLSs used by high school students at the High School at the Universidad Autònoma Chapingo.

References

Ali, L. F. & Zaki, S. (2019). Exploring vocabulary learning strategies across ESL/EFL contexts: Juggling between experiental and traditional modes of learning. Journal of Education and Educational Development, 6(2), 201-218. http://dx.doi.org/10.22555/joeed.v6i2.2756

Alqahtani, M. (2015). The importance of vocabulary in language learning and how to be taught. International Journal of Teaching and Education, 3(3), 21-34. https://doi.org/10.20472/TE.2015.3.3.002

Amirian, S. M. R., & Heshmatifar, Z. (2013) A survey on vocabulary learning strategies: A case of Iranian EFL university students. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 4(3), 636-641. https://doi.org/10.4304/jltr.4.3.636-641

Askar, W. A. (2015). A survey on the use of vocabulary learning strategies by ELT and ELL students of Duhok University in Northern Iraq. International Journal of English Language, Literature and Translation Studies, 2(3), 468-481. http://www.ijelr.in/2.3.15/468-481%20WISAM%20ALI%20ASKAR.pdf

Baleghizadeh S., & Ashoori, A. (2011). The impact of two instructional techniques on EFL learners’ vocabulary knowledge: Flash cards versus word lists. MEXTESOL Journal, 35(2), 1-9. http://www.mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=71

Barclay, S., & Schmitt, N. (2019). Current perspectives on vocabulary teaching and learning. In X. Gao (Ed.), Second handbook of English language teaching (pp. 799-819). Springer.

Bermejo del Villar, M. M., Girón Chavez, A. J., Cruz Maldonado, E. Y., Cancino Zamarrón, R. (2017). Learning strategies in EFL Mexican higher education students. https://www.lenguastap.unach.mx/images/publicaciones/Learning-Strategies-ebook.pdf

Carroll, D. W. (1999). Psychology of language. Brooks/Cole.

Cohen, A. D. (2011). Strategies in learning and using a second language (2nd ed.). Longman.

Cohen, A. D., & Aphek, E. (1981). Easifying second language learning. Studies in second language acquisition, 3(2), 221-236. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0272263100004198

Council of Europe (2001). Common European framework of references for languages: Learning, teaching, assessment. University of Cambridge Press.

de Vos, J. F., Schriefers, H., Nivard, M. G., Lemhöfer, K. (2018). A meta adnalysis and meta regression of incidental second language word learning from spoken input. Language Learning, 68(4), 906-94. https://doi.org/10.1111/lang.12296

Easterbrook, R.M. (2013). The process of vocabulary learning: Vocabulary learning strategies and beliefs about language and language learning [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. The University of Canberrra. https://researchsystem.canberra.edu.au/ws/portalfiles/portal/33684687/file

Fan, M. Y.. (2003). Frequency of use, perceived usefulness, and actual usefulness of second language vocabulary strategies: A study of Hong Kong learners. The Modern Language Journal, 87(2), 222-241. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4781.00187

Farjami, F., & Aidinlou, N.A. (2013). Analysis of the impediments to English vocabulary learning and teaching. International Journal of Language and Linguistics, 1(4-1), 1-5. https://doi.org/10.11648/j.ijll.s.20130101.11

Folse, K. S. (2004). Myths about teaching and learning second language vocabulary: What recent research says. TESL Reporter, 37(2), 1-13.

Griffith, C., & Cansiz, G. (2015). Language learning strategies: A holistic view. Studies in Second Language Learning and Teaching, 5(3), 473-493. https://doi.org/10.14746/ssllt.2015.5.3.7

Gu, P. Y. (2003). Vocabulary learning in a second language: Person, task, context and strategies. TESL-EJ, 7(2), 1-25. https://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume7/ej26/ej26a4

Hernández-Cueto, M. del C., Navarro-Hernández, M. del R., Ochoa-García, M. G., García-Ramos, M. (2016). La enseñanza de estrategias de aprendizaje de vocabulario en el nivel medio superior UAN. Revista EDUCATECONCIENCIA, 9(10), 6-22. http://tecnocientifica.com.mx/volumenes/V9N10A1.pdf

Krashen, S. (1989). We acquire vocabulary and spelling by reading: Additional evidence for the input hypothesis. Modern Language Journal, 73(4), 440-464. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1989.tb05325.x

Lessard-Clouston, M. (2013). Teaching vocabulary. TESOL.

Marin-Marin, A. (2005). Extraversion and the use of vocabulary learning strategies among university EFL learners in Mexico [Unpublished doctoral dissertation]. University of Essex. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/33994819_Extraversion_and_the_use_of_vocabulary_learning_strategies_among_university_EFL_students_in_Mexico

Nation, P. (2005). Teaching Vocabulary. The Asian EFL Journal, 7(3), 47-54. https://www.asian-efl-journal.com/sept_05_pn.pdf

Nation, I. S. P. (2008). Teaching vocabulary: Strategies and techniques. Heinle.

Nation, P. (2013). What should every ESL teacher know? Compass.

Oxford. R.L. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. Newbury House

Rasekh, Z. E., & Ranjbary, R. (2003). Metacognitive strategy training for vocabulary learning. TESL-EJ, 7(2), 1-15. http://tesl-ej.org/ej26/a5.html

Schmitt, N. (1995). The word on words: An interview with Paul Nation. The Language Teacher, 19(2), 5-7.

Schmitt, N. (1997). Vocabulary learning strategies. In N. Schmitt & M. McCarthy (Eds.), Vocabulary: Description, acquisition, and pedagogy (pp. 199-227). Cambridge University Press

Schmitt, N. (2007). Current perspectives on vocabulary teaching and learning. In J. Cummins & C. Davison (Eds.), International handbook of English language teaching (pp. 827-841). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-0-387-46301-8_55

unitedtranslations (8 may, 2018). The history of language translation. United translations: communicate beyond borders. https://www.unitedtranslations.com/great-history-of-language-translation/f

Ur, P. (2012). Vocabulary activities. Cambridge University Press

Vela, V., & Rushidi, J. (2016). The effect of keeping vocabulary notebooks on vocabulary acquisition and learner autonomy. Procedia-Social and Behavioural Sciences, 232(2016), 201-208. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2016.10.046

Wahyuni, S. (2013). L2 speaking strategies employed by Indonesian EFL tertiary students across proficiency and gender [Unpublished doctoral dissertation], University of Canberra. https://doi.org/10.26191/hwzy-nn57

Webb, S., & Nation, P. (2013). Teaching vocabulary. The encyclopedia of applied linguistics. Wiley-Blackwell.

Webb, S., & Nation, I. S. P. (2017). How vocabulary is learned. Oxford University Press

Wilkins, D. A. (1972). Linguistics in language teaching. MIT Press.

Zahedi, Y., & Abdi, M. (2012). The impact of imagery strategy on EFL learners’ vocabulary learning. Procedia-Social and Behavioural Sciences, 69(2012), 2264-2272. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2012.12.197