Introduction

From Teaching to Learning

Over the past 50 years, the emphasis on teacher and teaching has swung the pendulum towards a greater focus on the learner and learning (Blumberg, 2009; Cullen et al., 2012; Weimer, 2002). Current teaching methodologies, fueled by constructivist approaches are targeting learners’ autonomy, letting students construct their knowledge rather than “deposit” it, as obsolete thoughts prescribed. Hence, creating knowledge is not a simple act; learners must engage in the construction of new meanings (Stage et al., 1998). This shift has awakened EFL researchers’ interest in the topic to better understand how learners undergo the process of learning a second language (Hismanoglu, 2000). From the works of Rubin (1975) and Oxford (1990) until the most recent studies by scholars and academics worldwide (e.g., Erdogan, 2018; Weimer, 2002; Wong & Nunan, 2011; Wright, 2011), the understanding of how EFL learners process new information and use it has been increasingly more prominent in the literature on successful language teaching and learning. This understanding has led most teachers to consider essential concepts such as lifelong and self-directed learning as well as learning strategies and their contributions in their plans in order to foster good language practices.

Teaching can turn into an unethical act as teachers overlook the responsibility for providing students with opportunities to grasp effective learning skills and deepen their knowledge through lessons and practice at a challenging level (Nilson, 2013). This means that the learning process must be maximized by encouraging learning skills and aiming at in-depth knowledge. These two underpin lifelong learning. Lifelong learning is a common concern among teachers. This issue has become one of the major goals for higher education due to the need of shaping citizens capable of facing the challenges of a new era in the labor and technological fields. The American Association of Colleges and Universities (2002; 2007) and Wirth (2008a) have argued that lifelong learners must be able to acquire, retain, and retrieve new knowledge on their own by being independent, intentional, and self-directed (Colleges and Universities, 2002; 2007; Wirth, 2008a, as cited in Nilson & Zimmerman, 2013). To achieve such objectives, learners need to be aware of their cognitive processes and identify the strategies that can boost them. These and other essential elements in learning have led to the development of the concept self-regulated learning, which comprises both the cognitive management and assessment of the processes as well as the self-knowledge and regulation of the affective factors involved in language learning (Nilson & Zimmerman, 2013). In this sense, self-regulated learning may be one of the key pillars of effective learning.

Becoming a self-regulated learner is key to success in language achievement and in the academic field. Successful language learners go beyond the act of building effective skills and forming habitual practices; they incorporate useful learning strategies, hard work, and determination into their daily routine (Shuy, 2010). This is to say that students’ beliefs, motivation, discipline, and effort are not enough since there are strategies that contribute to the task management and accomplishment, but again, the teacher’s role is fundamental for students to know about the tools that can maximize their learning. According to Shuy (2010), learners must master (1) cognitive strategies, (2) the metacognitive component, and (3) motivation. The first refers to those strategies directly related to information processing. The second component includes declarative knowledge (knowledge about the factors influencing one’s performance), procedural knowledge (knowledge about one’s own tactics and other practices), and conditional knowledge (knowledge about the right time for strategy application). The third element, motivation, comprises self-efficacy (performance confidence) and epistemological beliefs (understanding of the source of knowledge). If students identify and incorporate these three components in their learning process, they may be self-regulated learners and therefore have more opportunities to be successful in reaching high-level language proficiency and achieve their academic goals.

According to Wolters (2015), teachers can promote self-regulated learning through very specific practices. Educators should motivate learners by encouraging confidence in their ability to learn and making students understand that what they are doing is important, useful, and relevant, and it will lead them to achieving high language proficiency and to success in academic life. In addition, teachers can help learners to develop skills to plan, set goals, and complete tasks. Students’ awareness of their progress is equally important. Therefore, feedback is necessary for students to know if they are meeting the course objectives. This reflection and awareness will also help learners build metacognitive knowledge that may eventually help them become more effective learners. Finally, Wolters (2015) also argued that promoting student understanding of effective strategies to build knowledge or develop abilities is essential for them to recognize what works best to become intended, independent, and self-regulated learners, which are essential elements to effective language learning. It is worth stating that not only students, but teachers are also vital stakeholders in the process of rediscovering the value of learning strategies in the language process.

The Value of Learning Strategies

The ultimate teaching goal for successful language performance is to empower students as autonomous learners through the use of both direct and indirect learning strategies. Instances of autonomy are evident as learners grow both psychologically and emotionally and are able to manage their own learning process by taking effective actions (O’Leary, 2014). Being a successful language learner entails being able to control the learning process, to be able to take one’s emotional temperature, and to develop a sense of community. In other words, being successful implies a high degree of autonomy to self-direct one’s own learning practices and processes. Oxford (1990) shed light upon the influence of learning strategies on successful learning. Learning strategies involve more than mental processes, which boosts learning as a holistic process. Although learning strategies are conditioned by different elements, they are also adaptable to learners’ needs and skills. Even better, learning strategies can become conscious decisions made by the learners that will eventually contribute to a more autonomous learning process. This decision-making can be taught to students. Therefore, in the pursuit of the appropriate means to fulfill optimal results in the learners, instructors play significant roles.

The author noted that learning strategies contribute to the major aim of communicative competence and specified some of the most significant characteristics. Such characteristics:

- Facilitate self-direction

- Expand the teacher role

- Are problem-based

- Are individual learning activities

- Include several aspects of the learner, not just the mental ones

- Boost direct and indirect learning

- Are not constantly visible

- Are often conscious

- Are taught

- Are adaptable

- Are shaped by an array of factors

However, experts on education still question why some students do not employ learning strategies effectively. Schechtman (2019, as cited in Goetzke, 2019), in her article Why Don’t Students Use Effective Learning Strategies? A Reflection posited three main answers to this question: Unawareness, illusions of competence, and too much effort and time. She explains that learners are unaware of the importance of retrieval practice (bringing information to mind); they use techniques that give them a false sense of competence (e.g., rereading, reviewing); and they believe that learning about and using new strategies will require more effort and be time consuming. To solve these three issues, the author suggests teaching the strategies explicitly in class and developing some activities containing the strategies for students to recognize their importance and effectiveness (Schechtman, 2019, as cited in Goetzke, 2019). These actions may motivate students, boost their autonomy, and encourage intended and self-directed learning. Therefore, students must know about and know how to implement learning strategies.

Learning strategies are successful mechanisms that “make learning easier, faster, more enjoyable, more self-directed, more effective, and more transferable to new situations” (Oxford, 1990, p.8). To this thought, Allwright (1990) and Little (1991) added that learning strategies help students develop autonomy in the language learning process, becoming lifelong learners. It is evident that employing learning strategies is of great importance in the language learning process, but it is equally important for teachers to provide students with opportunities to develop the different strategies and guide learners in the process of using them. This premise is supported by Hismanoglu (2000), who claimed that students could become better language learners when they are supported by teachers who are interested in developing both communicative competence and language learning strategies. Hence, knowing about and employing different learning strategies must be of paramount importance to become a successful language learner.

Learning Strategies: Direct and Indirect

Learning strategies, the choices made by students to achieve success in the acquisition of knowledge, are “specific actions, behaviors, steps, or techniques – such as seeking out conversation partners, or giving oneself encouragement to tackle a difficult language task – used by students to enhance their own learning” (Scarcella & Oxford, 1992, p. 2). These actions, behaviors, steps, or techniques make students develop metacognition and provide the autonomy both teachers and students seek. Having said this, it is necessary for students to know the different types of strategies, how to use them, and why to use them, since as Cano de Araúz (2009) asserted, “the more aware learners are of the strategies they employ (why use them), the more effective and skillful learners they will be” (p. 400).

Learning strategies are split into two most important categories: direct and indirect strategies. Each of these types is comprised of three categories. The first type, direct learning strategies, are broken into cognitive, memory-related, and compensatory strategies. Oxford (2001) remarked that cognitive strategies are those that allow learners to handle information in a direct form. Among the strategies found in this first category are reasoning, analyzing, note-taking, outlining, and summarizing. Memory-related strategies make concept linkage possible. This may be achieved by using mental images, sounds, acronyms, body movement, printed material such as flashcards, and location. Compensatory strategies, as the first word implies, compensate for missing knowledge. As noted above, direct strategies (cognitive, memory-related, and compensatory) are linked to the mental processing of language. These are in charge of helping the students internalize and retrieve the information to achieve language proficiency.

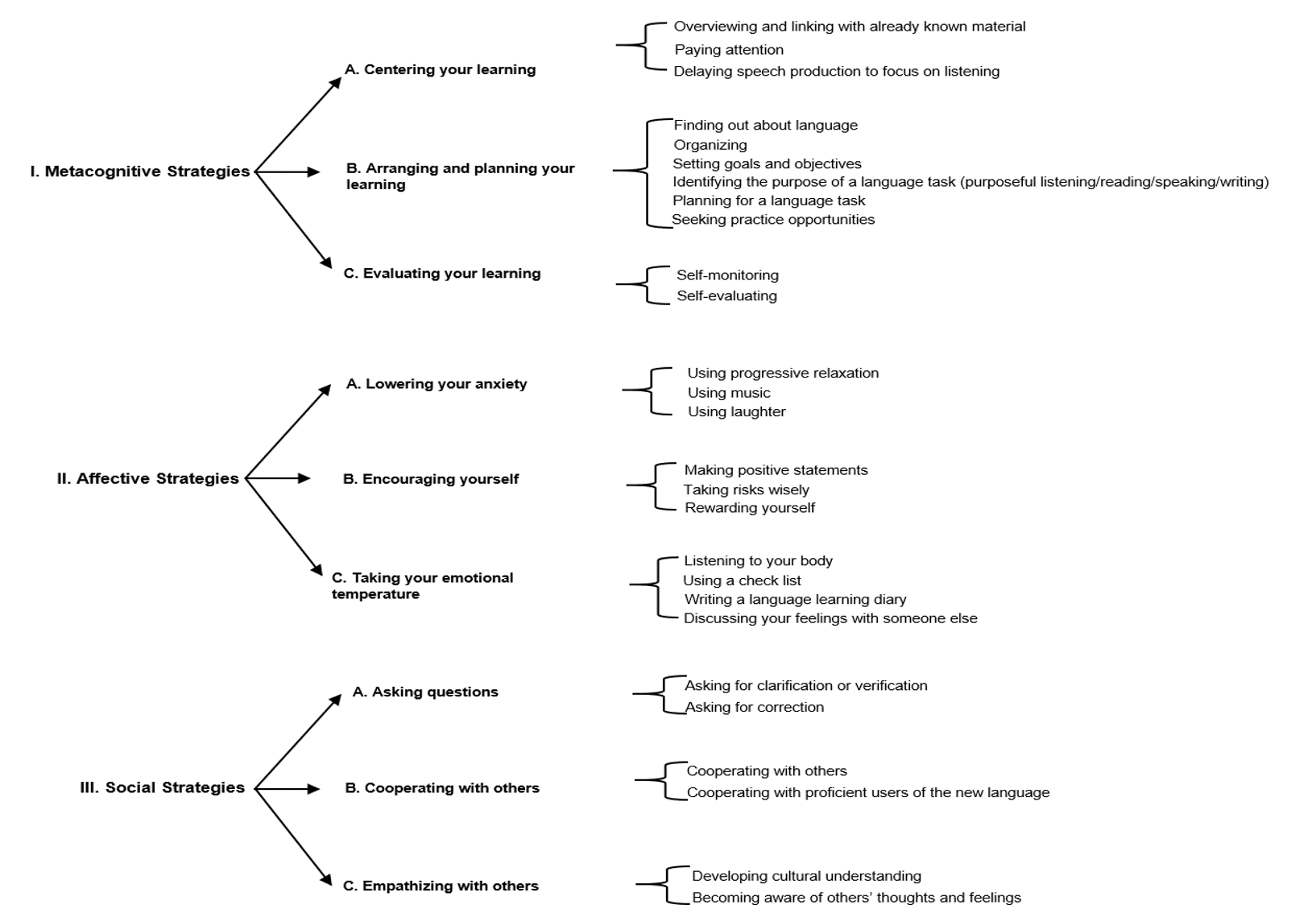

The second type of learning strategies, indirect learning strategies, is likewise divided into three categories: metacognitive, affective, and social (See Figure 1). Oxford (2001) detailed that metacognitive strategies help students manage the learning process entirely. This means that students are able to decide what is most suitable for them according to their needs. Students can gather and organize materials, plan for a task, create a study schedule, monitor mistakes, and evaluate the accomplishments. On this matter, Chamot (1988) emphasized the significance of generating this kind of self-awareness that promotes reflection, task procedure set-up, continuous performance check-up, and task assessment after its realization. Oxford (2001) also explained that affective strategies are those related to students’ moods and feelings. Some of these strategies could be knowing the levels of anxiety, deep breathing, praising oneself, and thinking and talking positively. Lastly, social strategies have to do with the sense of community, and as a community, people interact and communicate. Asking questions to get verification, working collaboratively, taking part in conversations, and understanding the target culture are among the most common social strategies suggested by the author. In short, indirect strategies (metacognitive, affective and social) allow for control of the learning process; they allow students to decide what to do and how to effectively do it.

Note: Taken from Ehrman and Oxford (1990).

Figure 1: Categorization of Indirect Learning Strategies

Effective Language Learning

Effective language learning seems to depend on three main variables: aptitude, motivation, and opportunity. This means that students not only need the innate ability to learn a language but also strong sources of motivation, as well as opportunities to develop their linguistic competence while being autonomous and in control of their own learning (Rubin, 1975). Such opportunities may be provided by both the language instructor and the learner if they are aware of the needs and strategies that could maximize learning. Nonetheless, to develop an effective learning environment and encourage skillful learners, it is not enough to just know about these key elements; it is essential to employ them inside and outside the classroom. In this sense, language teachers have a responsibility to show students different paths and to guide them through the process. This teacher guidance toward learner autonomy may be possible if the instructors see beyond cognitive, memory-related, and compensation strategies to achieve language proficiency. Teachers as well as students need to realize the significant role of indirect learning strategies in successful language learning and teaching.

Successful language learning is a subject of profound discussion. Experts such as Nunan (1999) believed that motivation, risk-taking, and having opportunities to practice the language are essential factors to reach this goal. These elements are shared by other researchers following Philp (2017) who affirmed that aptitude, learners’ individual differences, motivation, and teacher and peer support are fundamental in the language learning process to achieve success. This means that the ability to communicate appropriately in different contexts not only involves being skillful at language learning but also having a positive attitude, while being assisted by teachers and classmates. Thompson (2005) agreed with Nunan and Philp on the essential components to become a successful language learner. She contended that if the students are motivated to learn, understand their capabilities, are patient and willing to take risks, make mistakes and receive feedback, and practice effective learning strategies, they are effective learners and will likely become proficient language speakers. These shared beliefs reveal a clear pattern in the language learning process. Thompson (2005) also talked about learning strategies, which are of high significance in the process as well.

Even beginner learners may be aware of what works best for them when practicing the language. They may notice that using visual material is convenient or that working alone is favored because of an introverted personality. Students may also handle material in different ways, from note-taking to guessing from context. The previous examples are common patterns in language learning, and they are identified by experts as learning strategies. The former entails general approaches that guide learning behavior while the latter entails specific actions or techniques used to maximize learning (Oxford, 2001). Put into different words, students determine what is most suitable for them because there are certain elements that condition learning.

Being a successful and lifelong learner requires thorough control of the process. Thus, the problem arises when students do not manage learning strategies effectively. It is then fundamental that students be cognizant of the existence of such strategies, and identify which strategies are more effective and appealing so that they can maximize their learning. This premise has also been proven in several other studies, such as the ones conducted by Clouston (1997), Dreyer and Oxford (1996), Giang and Tuan (2018); Hismanoglu (2000), Oxford et al. (1998), Panzachi and Luchini (2015), Purpura (1999), Rubin and Thompson (1982), Véliz C. (2012), and Wong and Nunan (2011), which argue that successful and effective language learners are those, who in their autonomy, select the most appropriate learning strategies.

Studies of Learning Strategies in EFL Contexts

While several studies have been carried out on direct strategies, indirect strategies have more recently been under scrutiny. In this vein, indirect strategies are attracting the experts’ attention. They are now discovering that metacognitive, affective, and social factors have significant influence in the language learning process and that the pendulum must also swing towards indirect learning strategies as part of a comprehensive approach to successful language teaching and learning. Considering this, it is remarkable to delineate the contributions of several research studies. The works consulted glean significant aspects that will help construct an understanding of the importance of indirect strategies in second language teaching and learning through the specification of two different orientations.

The first orientation focuses on works that contribute to raise the importance, once minimized, of indirect learning strategies. These studies provide evidence of the necessary switch of focus from direct to indirect learning strategies. Researchers such as Rubin and Thompson (1982), claimed that successful language learners are those in control of their own learning. They know how to both use the language and manage their learning. Wong and Nunan (2011) added that learning strategies foster students’ responsibility in their own language learning and personal development. This suggests that learning how to learn is essential. In this sense, students need to be aware of not only the what (the knowledge they are constructing) but also the how (strategies used to construct meaning). By knowing the what and the how of language learning, students may become reflective and critical learners, and they may manage their learning process more effectively. Panzachi and Luchini (2015), reported on the results of a case study about the cognitive process and the language learning strategies used by one EFL learner in achieving language proficiency. The results determined that the deliberate use of an array of direct and indirect language learning strategies might lead students to become effective English language learners. Furthermore, the quantitative research work by Giang and Tuan (2018), investigated the language learning strategies employed by EFL freshmen in a Vietnamese school. The correlational study revealed how the student’s employment of the strategies varied according to their linguistic proficiency. The research findings showed that the selection and use of language learning strategies determine the success of language teaching and learning.

The second orientation comprises works that maximize the role of indirect learning strategies by drawing strong conclusions on how they influence learners’ independence, autonomy and L2 proficiency. In this regard, Véliz C. (2012) carried out a case study corroborating that the indirect strategies that stood out are metacognitive, planning and monitoring. The author noted that metacognitive strategies, when used along with direct strategies such as mental images, applying images and sounds, practicing, analyzing/reasoning, and paying attention are promoted, and that motivation is increased as a strategy repertoire is devised. Also, authors such as Hismanoglu (2000) found that developing skills in the metacognitive, affective, and social areas may help students to build independence by taking control of their own learning (para. 24), while Lessard-Clouston (1997) claimed that using such strategies might contribute to the students’ progress on their linguistic competence. Purpura (1999) also found that metacognitive strategies influence the use of cognitive strategies directly and positively, which evidences the relevance of metacognitive strategies in the fulfillment of learning tasks. In addition, studies of EFL learners carried out by Dreyer and Oxford (1996) in South Africa, and by Oxford et al. (1998) in Turkey indicated that metacognitive, affective, and social strategies help predict L2 proficiency. As it has been demonstrated, indirect strategies are necessary to enhance learning since they complement the cognitive processes developed through direct language strategies; therefore, a comprehensive and balanced methodology should be considered for students to maximize their learning process.

Method

This study explored the use of MAS indirect learning strategies by a group of university students. It attempts to answer the following questions:

- To what extent are MAS indirect learning strategies used by students of the Associate degree in English and the English Teaching major from Universidad Nacional of Costa Rica, Pérez Zeledón Regional Campus?

- What MAS indirect learning strategies are the most and the least encouraged by professors of the Associate degree in English and the English Teaching major from Universidad Nacional of Costa Rica, Pérez Zeledón Regional Campus?

- What language activities can be suggested to boost indirect learning strategies?

This paper reports quantitative and qualitative data to determine the extent to which MAS indirect learning strategies are used by university students to maximize their language development. The scope of the study is descriptive. Gall et al. (2007) asserted that descriptive research intends to describe a phenomenon and its main features. It focuses more on the area explored rather than the reasons why something occurred. This descriptive study relied on the development of a case study. Simons (2009) defined case studies “as an in-depth exploration from multiple perspectives of the complexity and uniqueness of a particular project, policy, institution, program or system in a ‘real life’” (p. 21). In this regard, the analyses will be based on the insights and perspectives of a group of university students of the Associate degree in English and the English Teaching major as well as of Faculty teachers at Universidad Nacional of Costa Rica.

The Participants

The setting of this study took place at the Universidad Nacional of Costa Rica, Pérez Zeledón Regional Campus, one of the five national public universities. The sample population is representative and will be studied through a non-probability sampling design. The students were deliberately selected. The sample population consisted of 27 students from the English Teaching major and 23 from the Associate degree in English. This population amounted to 50 students. Students aged 20 to 23 years old. The group was composed of 32 female students and 18 male students. Also, six professors of the Language Faculty were part of the population surveyed. These professors’ teaching experience ranged from 4 to 20 years in the field. It is worth noting that the population of participants is composed of two different groups of students. One group is studying a four-year English Teaching degree while the other is pursuing a two-year English Associate degree. However, they both go through the same process of struggling with the language during the initial year of study. This process is necessary to adopt new learning strategies if they hope to succeed as good language learners. Due to the characteristics of this sample population, the researchers analyzed the limitations of this research study and were aware of their scope, particularly when generalizing the results.

The Procedure

Instruments

To carry out this case study, two questionnaires involving quantitative and qualitative data were designed and administered. The first instrument aimed at identifying the most and least used MAS indirect learning strategies through a student questionnaire. It was composed of one section for personal information and a close-ended section for the use of indirect learning strategies. For the collection of the information in the second section, a summative five-point Likert scale was constructed. The scale includes the following predetermined values: Very much, Much, Average, Little and No use. The list of strategies used for this second section was taken from the Oxford’s (1990) Strategy Inventory for Language Learning. The third section of this questionnaire entailed an open-ended item. The qualitative data expected to be gathered included general comments about specific and personal uses of indirect learning strategies through the students’ language development process in the lower and upper years. Also, it attempted to determine whether professors of the Language Faculty encourage students to use the MAS learning strategies, and list and add any new strategy to the inventory.

The second instrument intended to determine the extent to which professors have encouraged the use of MAS indirect learning strategies. It was also composed of one section for personal information and another one for a close-ended item to identify the extent to which these strategies have been reinforced by professors. For the collection of the information in the second section, a summative five-point Likert scale was constructed. Values such as: Very much, Much, Average, Little and No use are included in this scale. The third part of the questionnaire gathered general information about the indirect learning strategies professors have encouraged in their learners the most and any other different strategies they have promoted with their students. The administration of the questionnaires to the two groups of participants was carried out in two different sessions. During these sessions, both researchers were available to guide the respondents by explaining the different items of the instruments and to clarify the statements pertaining to each type, category and subcategory of the indirect learning strategies in order to avoid misinterpretation and facilitate comprehension of the statements on an equal rate. For the most part, the questionnaires included a combination of Likert scales to compile the degree to which respondents agreed or disagreed with the statements given by using an ordinal psychometric measure. Although these types of scales were very easy to grasp by the respondents, they may fail to measure the true attitudes of the participants as they are just given five options and, therefore, they may avoid selecting the lowest or highest points. Then, one may tend to interpret the respondents’ selection on a more or less normal distribution without assuming the previous disadvantage. On this account, the researchers compromise to take care of the generality of any results drawn from the analyses of the Likert scales in the questionnaires.

The tables displayed in the following section show the calculation of the mean scores derived from the analyses of the Likert scales according to the statements of each type, category and subcategory of the indirect learning strategies in the different parts of both questionnaires. The given values in the 5-point Likert scale were specified and explained to the respondents as to avoid confusion and avoid ambiguous answers: Very much, Much, Average, Little and No use. These answers were weighted 5, 4, 3, 2, and 1, respectively, and represented on an interval scale from 0 to 5.

Results

The data analysis was based upon the information gathered through the student and teacher questionnaires. The purpose of this section was to answer the research questions by determining the extent to which MAS indirect learning strategies are used by students of the Associate degree in English and the English Teaching major from Universidad Nacional of Costa Rica, Pérez Zeledón Campus, to identify the most and least encouraged MAS learning strategies by professors, and suggest activities to boost indirect learning strategies for EFL teachers in general.

The extent to which MAS indirect learning strategies are used by students of the Associate degree in English and the English teaching major and promoted by professors.

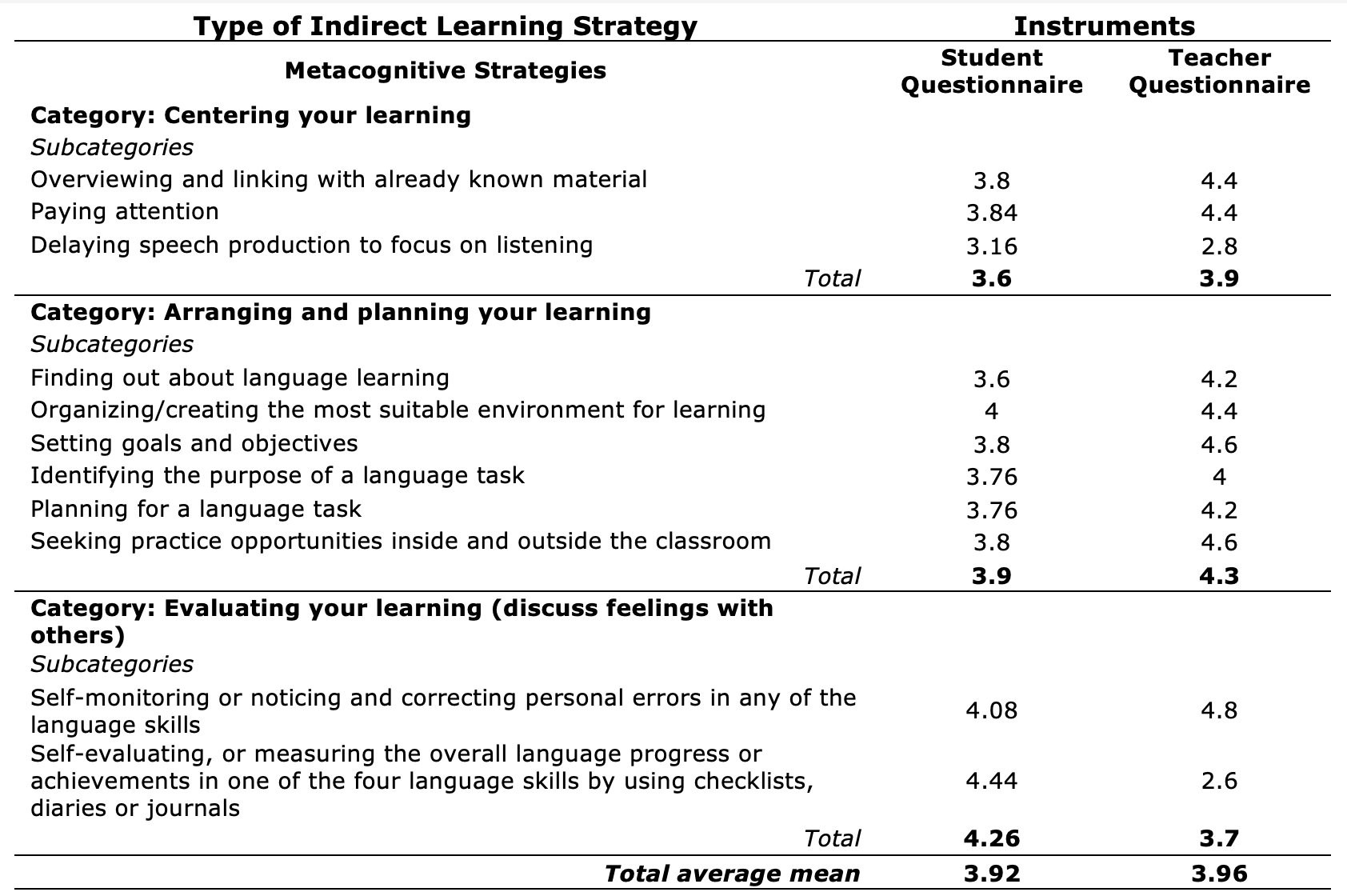

According to Oxford (2001), metacognitive learning strategies are those cognitive devices employed by learners to self-regulate their own learning. They are split into three different categories: centering your learning, arranging and planning your learning and evaluating your learning. In this regard, the most striking findings of this section show that the most used category by students was evaluating your own learning, whereas centering your learning was the least used. In contrast, the teachers’ most encouraged metacognitive strategy was arranging and planning your learning and the least promoted was evaluating your learning (See Table 1).

Note: Information derived from the analysis of the Student and Teacher Questionnaire.

Table 1: Metacognitive learning strategies used by students and encouraged by teachers

As noted before, among the three main metacognitive categories described by Oxford, the one that is most used by the sample population of students was evaluating your learning. Indeed, self-evaluating by using checklists or diaries recorded the highest mean of a category group. Namely, a great majority reported the use of this strategy as very much and much used. In contrast, this was the least recommended by professors among all the category groups. They revealed through this answer that rarely have they implemented checklists and diaries to help students self-evaluate or measure their language achievements. The category pertaining to the metacognitive strategies that was the least used by the group of learners scrutinized was centering your learning. Even though students seem to have used overviewing and linking with already known material, paying attention and delaying speech production to focus on listening to a very satisfactory extent, it is the category group with the lowest mean. Among these strategies, the least used by students was delaying speech production to focus on listening. Actually, it was also the second least promoted strategy by professors.

One of the least used strategies by these learners among all subcategories of the metacognitive ones was finding out about language learning. More than half reported to have used this strategy, but not very much. Nonetheless, a percentage (8%) does not use the strategy at all. Another aspect worth noting is the subcategory setting goals and objectives. Students seem to identify their goals and objectives as they take the lessons. Certainly, this is one of the highest means recorded through the questionnaire. A very small percentage specified to have never used this indirect learning strategy.

Regarding professors, this category also scored one of the highest means. Namely, they have encouraged the use of this strategy to a great extent. Furthermore, the subcategory identifying the purpose of a language task recorded one of the highest means as well. Just 12% of the students surveyed reported that they have never used it or have used it to a minimum extent. The other 88% reported a very satisfactory use of the subcategory in their language development. Concerning professors, this subcategory scored an average mean, not too high not too low.

The last category of the metacognitive strategies is evaluating your learning. Students reported that they self-monitor and correct personal linguistic errors less than they self-evaluate their overall language progress through checklists, diaries or journals. This last category of metacognitive strategies is the second in which students recorded the highest mean among the other categories. Certainly, 68% of the students recorded very much and much for the use of this category. Just 32% scored an average mean, which is still a positive result. In the case of professors, this category of metacognitive strategy is the lowest.

Regarding the professors surveyed, the category of the metacognitive strategies most encouraged by professors was arranging and planning your learning. Certainly, this category comprises two subcategories with the second highest mean among all other subcategories of the metacognitive strategies. These subcategories are setting goals and seeking practice opportunities inside and outside the classroom. Centering your learning is the second highest and evaluating your learning is the lowest of all the types of metacognitive strategies promoted by these professors. Delaying speech production to focus on listening is the second least fostered subcategory of the arranging and planning your learning category.

Professors seem to be inclined to have students produce oral language quickly and not to delay their focus on aural skills. Actually, a great percentage of them reported that they partially reinforced this subcategory of the metacognitive strategies. Identifying the purpose of a language task is the lowest fostered subcategory within the category arranging and planning your learning according to teachers. Concerning this subcategory, professors seem to encourage students to identify the purpose of a language task to a satisfactory extent, as a great majority reported that they have promoted this in their teaching routine.

Evaluating your learning, which is the last category of the metacognitive strategies, was reported as the least used metacognitive strategy by professors. Certainly, self-evaluating the overall language progress by using diaries stated the lowest mean among all metacognitive subcategories. The professors indicated that they do not use it to a great extent, and 20% reported that they have never encouraged this category.

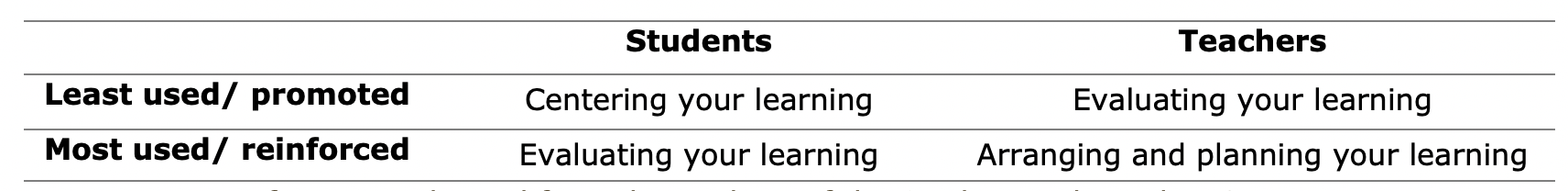

In sum, in order to visualize the least and most used category of the metacognitive strategy group, the following table shows the findings of this section:

Note. Information derived from the analysis of the Student and Teacher Questionnaire.

Note. Information derived from the analysis of the Student and Teacher Questionnaire.

Table 2: Metacognitive strategies results

The following types of indirect learning strategies are the affective ones. They are broken down into three categories: lowering anxiety, using self-encouragement, and taking your emotional temperature. They facilitate gaining control as learners are able to “identify [their] mood and anxiety level, talk about feelings, reward oneself for good performance, and use deep breathing or positive self- talk ” (Oxford, 2001, p. 14). Concerning the last category, by employing different tools like journals, reflections, diaries and questioning, learners might be able to “take their temperature” as they develop an understanding or self-awareness of how they are doing with the language in a specific task. After checking their “temperature” they might become mindful of their own linguistic strengths and weaknesses by programming a set of actions in order to improve their performance in similar tasks later on.

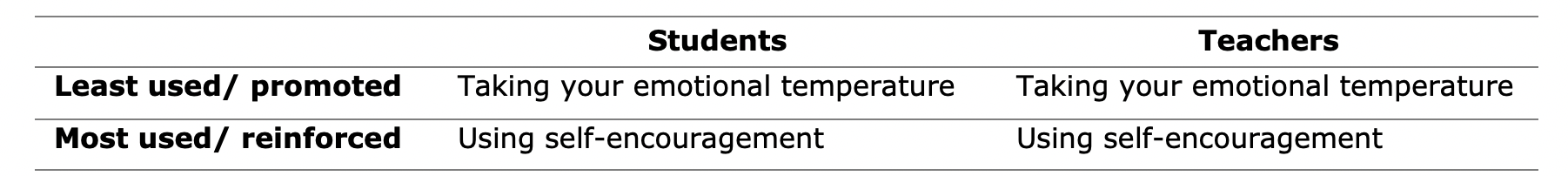

From the analysis of this section, several enlightening points are derived. First, from the students’ perspectives, the most used category of this type of indirect strategy was self-encouragement. This was the most promoted strategy by teachers. On the other hand, the least used category by students was taking your emotional temperature, which was the least reinforced category by the teachers as well (See Table 3).

Note: Information derived from the analysis of the Student and Teacher Questionnaire.

Table 3: Affective learning strategies used by students and encouraged by teachers

As pointed out before, according to the information gathered through the student and teacher questionnaires, the category from the affective learning strategies least practiced and encouraged respectively was taking your emotional temperature. Students and professors alike scored a low mean in this category.

Lowering anxiety is the second strategy that scored the lowest mean among all the categories of the affective learning strategies. Certainly, one of the subcategories belonging to this category group that scored an average mean was using progressive relaxation, deep breathing or meditation. It was interesting to analyze how varied the percentages for the means were. Just 36% reported a very satisfactory use of this strategy. 32% reported an average use, and another 32%, stated that they have never used it or used it little. Using self-encouragement reported the highest mean. Taking risks wisely was reported with the highest mean. Making positive statements and rewarding yourself through visible or intangible rewards was the second highest mean. For this last learning subcategory, students scored 68% of satisfactory use. Additionally, 32% of the surveyed students have partly used it, used it little or not used it at all.

The subcategory within the type taking your emotional temperature that scored the lowest mean was writing a language learning diary. Indeed, this was also one of the lowest scores for teachers. The distribution of percentages for this subcategory shows that just 64% of the students reported that they have used it to a very satisfactory extent. However, 36% of the student sample population reported that they have partly used this strategy or have used it little.

Concerning professors, the category from the affective learning strategies least promoted was taking your emotional temperature, the most encouraged was using self-encouragement (See Table 3) and the second highest mean scored was lowering your anxiety. Regarding the latter type of affective learning strategy, the subcategory using music before any stressful task was the one with the lowest mean. More than half of the professors reported that they have not encouraged the use of this indirect strategy. Although Ehrman and Oxford (1990) suggested that music relieves anxiety and can be used before a challenging task, and left it open for teachers to select the most suitable kind of music for their students. The researchers tend to believe that what teachers might do is to survey students for their music preferences to make this strategy work more effectively. The most appropriate music genre is an issue that might draw the researchers’ attention to conduct a further study. Nevertheless, Geng et al. (2019) stated that “the genre music needs to be discussed, however, something relatively mellow, and easy listening would ensure that students are getting their ‘music fix’ without completely blocking out their surroundings and ability to be mindful learners” (p. 96).

Less than 20% reported that they have used it very much and 17% stated that they have used it occasionally. Among the subcategories of the second category of the affective learning strategies using self-encouragement, rewarding yourself through visible or intangible rewards obtained the lowest mean. Even though it is the lowest, it still scored a satisfactory mean. 60% of the professors seem to have encouraged its use to a very satisfactory extent.

Using a checklist for identifying your emotional state in general or related to particular language tasks and skills is the affective learning strategy that scored the lowest according to professors and the second lowest according to students. A great majority of students stated that they have not used this strategy before to become aware of their emotional state when performing specific tasks.

Writing a language learning diary is the lowest mean scored by students and the second lowest by teachers. In fact, most students surveyed have not used this strategy whatsoever, although some reported that they have done it at one point in their studies in the major. In the case of teachers, this strategy is also one of the lowest. Teachers reported that they do not apply or foster that strategy very often.

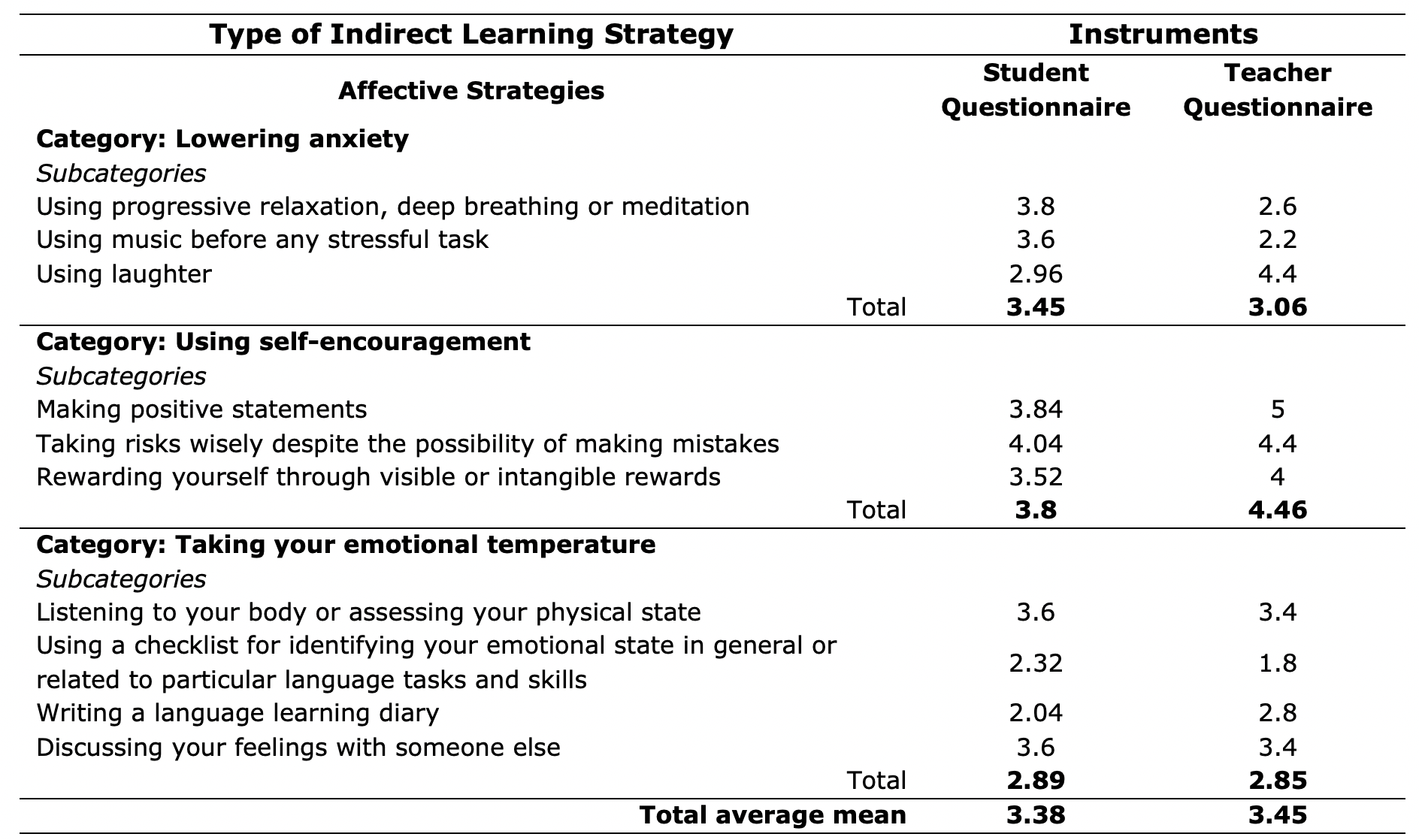

Table 4 below summarizes the main findings of this section of affective learning strategies:

Note: Information derived from the analysis of the Student and Teacher Questionnaire.

Table 4: Affective Strategies Results

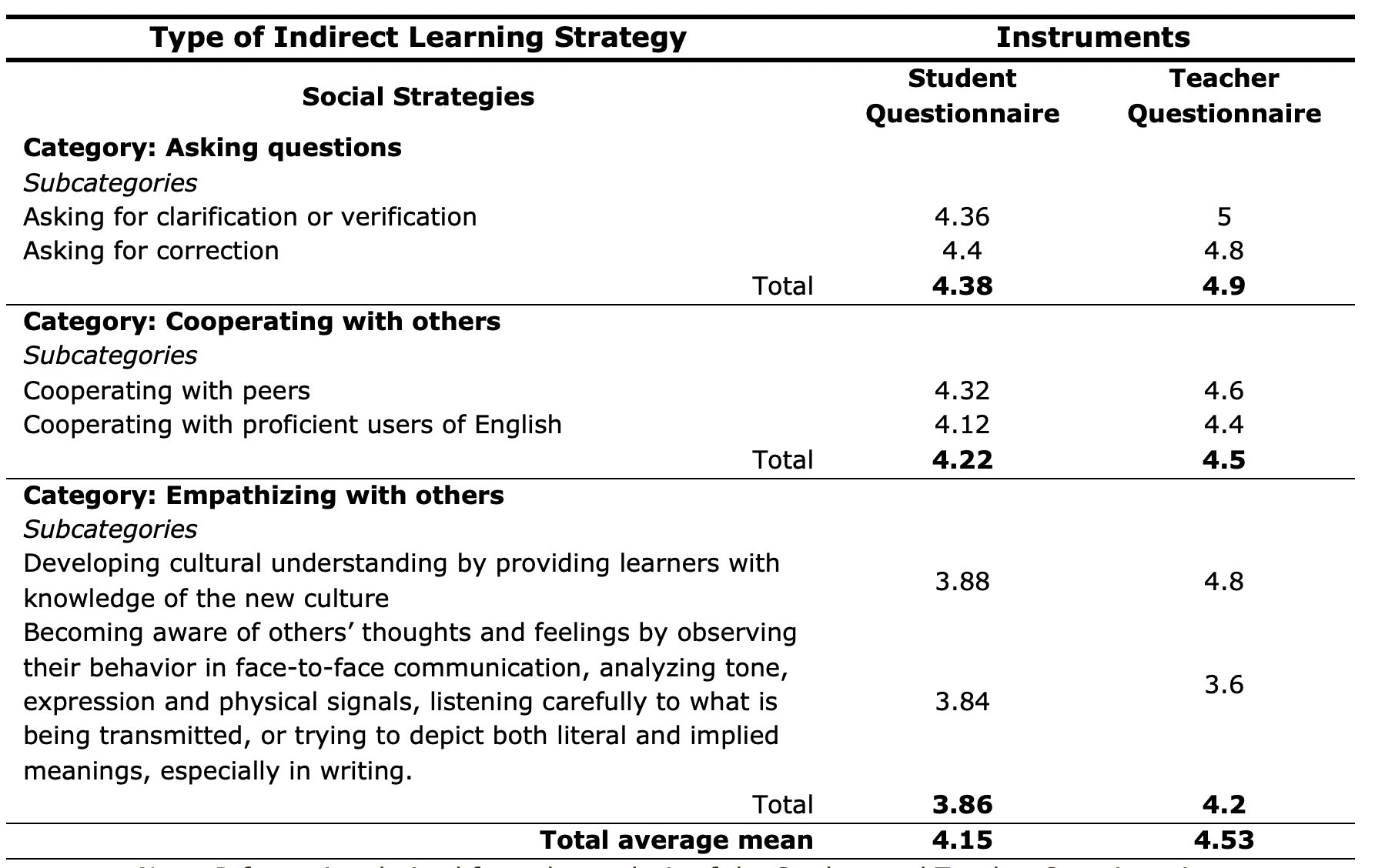

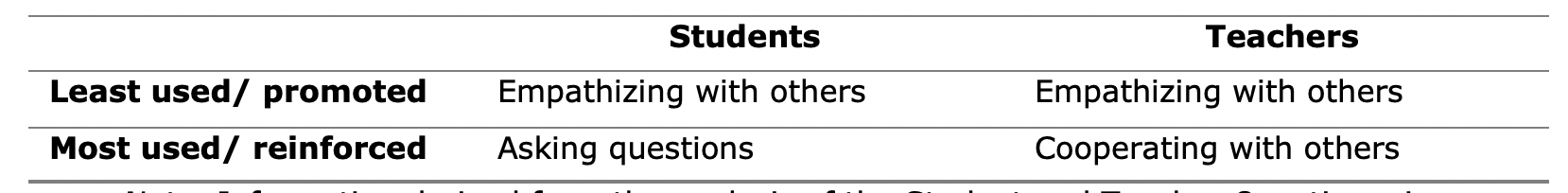

The last type of indirect learning strategies is social strategies. Their use involves language to communicate and interact. Language, indeed, entails a social act where communication is a common and necessary practice occurring between and among the interlocutors (Oxford, 2001). For students to interact and communicate, they need to build up their own strategies to understand others and be understood, to comprehend the target language and culture. This group of strategies is broken down into some categories such as asking questions, cooperating and empathizing with others. The data analysis of this section reveals remarkable points later discussed in the conclusion of this study. First, based on the students’ responses, the most used social strategy was asking questions, whereas the most encouraged social strategy according to teachers was cooperating with others. Second, the least implemented and fostered social strategy by students and teachers respectively was empathizing with others (See Table 5).

Note: Information derived from the analysis of the Student and Teacher Questionnaire.

Table 5: Social learning strategies used by students and encouraged by teachers

Based on the information gathered, the students manage these strategies at a satisfactory level. All the means are above 3 which is the average of the Likert scale used. For the first category asking questions, students tend to ask for correction more than for clarification or verification. A large percentage of the students surveyed 88% ask for correction as they communicate in the target language. Just 12% of them handle this strategy averagely or very little. In the case of teachers, they promote asking for correction and asking for clarification almost at the same level. The former scored just 0.2 higher than the latter. Indeed, asking for clarification was reported by all professors with the highest score. They all indicated that they promote this indirect learning strategy in the classroom.

The second category cooperating with others was the second most used according to students surveyed. Among the subcategories in this respect, cooperating with peers received the highest score according to students’ responses. On the other hand, cooperating with proficient users of English scored lower, but still it was a strategy used to a satisfactory level. In fact, 77% of the students used it more frequently. In addition to this, teachers surveyed have fostered the use of the strategy cooperating with peers more than cooperating with proficient users of English. It is worth noting that both subcategories still received a high mean according to teachers.

The next category of the Social Indirect Learning Strategy is empathizing with others. Based on the findings, this was the lowest category of the social indirect learning strategy for both participant groups. This category is composed of two subcategories Developing cultural understanding by providing learners with knowledge of the new culture andBecoming aware of others’ thoughts and feelings. Among these subcategories, the former received the highest score and the latter the lowest based on the students’ responses. Although 64% of the students reported to use it to a satisfactory level, 36%, which is a significant percentage, reported to use it averagely or not to use it at all. In the case of teachers, they indicated that the second subcategory becoming aware of others’ thoughts and feelings is not a strategy that they implement or foster often. In fact, this subcategory scored the lowest among all the social learning strategies subcategories for teachers. In the case of the first subcategory Developing cultural understanding by providing learners with knowledge of the new culture, teachers declared that they implement it and promote it to a very significant level. Actually, this subcategory is one of the highest subcategories according to teachers’ responses.

Briefly, the social strategies most/least used by students and most/least promoted by teachers can be visualized in Table 6.

Note: Information derived from the analysis of the Student and Teacher Questionnaire.

Table 6: Social Strategies Results

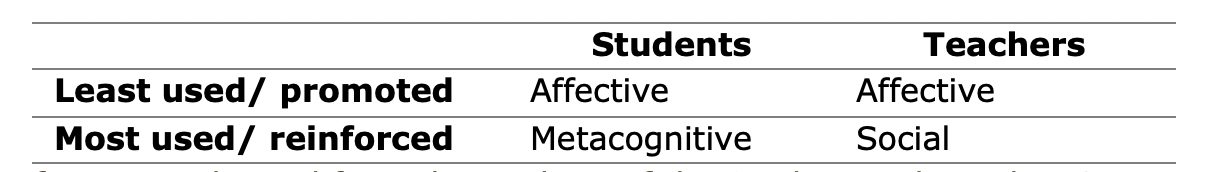

In summary, based on the main findings of this data analysis section, it is worth noting the least and most used or reinforced MAS strategies. The following Table 7 gives evidence of these.

Note: Information derived from the analysis of the Student and Teacher Questionnaire.

Table 7: MAS Indirect Learning Strategies Results

To conclude, the most outstanding findings are worth mentioning. Regarding students, the most used type of indirect learning strategy is the metacognitive strategy. Second is the social strategy, and the least used type is the affective strategy. The least used category of the metacognitive strategies is centering your learning. This shows that not all students are aware of strategies that can facilitate the way they learn. They are more aware of strategies that help them arrange, plan and evaluate their own learning. Regarding the social learning strategy, the category least used is empathizing with others. Both subcategories of this group are the lowest of the social strategies. The most used category of the social strategy is asking for questions. Concerning the lowest-scored type of indirect learning strategy, the affective strategies are at the bottom of the list. The most used category of this type is using self-encouragementand the least used is taking your emotional temperature. It is worth mentioning that the subcategory of this group with the lowest score is writing a language learning diary.

Second, referring to teachers, the most encouraged indirect learning strategy in the development of the courses they teach is social strategies and the least reinforced is affective strategies. Metacognitive strategies are the second most encouraged by teachers. Concerning the type of the social strategies, the category most fostered by teachers in the activities they develop or recommend inside and outside the classroom is cooperating with others and the least reinforced is empathizing with others. In terms of metacognitive strategies, evaluating your learning was given the highest scored, and arranging and planning your learning the lowest mean. Based on the affective strategies pointed out, teachers reported to have reinforced using self-encouragement more often. On the other hand, taking your emotional temperature was the lowest category.

Language activities suggested to boost indirect learning strategies in students of the Associate degree in English and the English Teaching major recommended by professors.

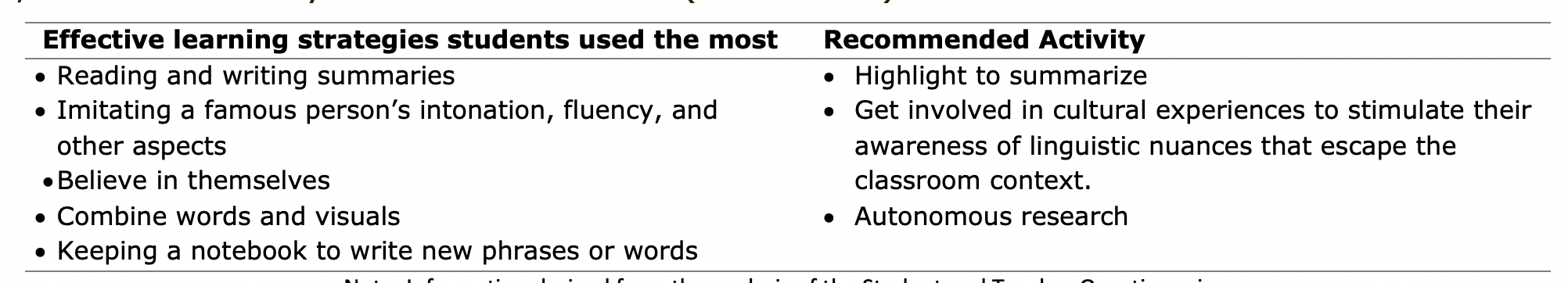

Section 3 of the teacher questionnaire allowed researchers to indicate an array of different strategies that teachers recommend implementing along with the customary activities of the courses of both language programs. In an open-ended item, teachers expressed the most effective strategies that students have used, and the ones they recommend the most (See Table 8).

Note: Information derived from the analysis of the Student and Teacher Questionnaire.

Table 8: Activities to Boost Indirect Learning StrategiesAccording to the responses given, teachers detected that the most successful strategies derive from the metacognitive group. Their recommendations entail employing social and metacognitive strategies as well. The affective strategies are not part of the activities suggested.

Limitations of the Study

As stated before, this research study is based on a small sample population composed of 27 students of the English Teaching major and 23 students of the Associate degree in English of UNA, Pérez Zeledón Regional Campus. Hence, researchers avoided the generalization of the results obtained to all contexts but provided ample detail for other readers to make decisions upon the extent to which the results might be relatable to their settings (Ravitch & Mittenfelner, 2016). On this account, Thomas (2011) asserted that if the results were applicable to this group of learners, they may be generalizable to other cases and individuals with similar characteristics.

Although the selection of participants from the English Teaching major may lead the reader to think that their awareness towards learning strategies tends to be stronger and that this group of students are more likely to be “good language learners,” it is necessary to make clear that in the first two years of their studies, both groups take the same courses of Integrated English I, II, Composition, Basic Grammar, Oral Expression (Society and Humanism; Commerce and Economy; and Science and Technology), Reading, Culture I and II, which means that their awareness towards learning strategies may be raised equally.

Another limitation of this study relates to the fact that students from different proficiency levels were included in the sample population. It is worth stating that the essence of this research study is limited to the frequency in which the indirect learning strategies have been applied as these groups of learners grow in language proficiency. From this perspective, this research study may open a window for further discussion on the relation of indirect learning strategies use and level of proficiency. The fundamental objective is to stir interest in the use of indirect learning strategies in the students and boost learning strategy-based instruction to enhance successful language learning and teaching.

Discussion

The present study aimed at examining the use and enhancement of metacognitive, affective, and social indirect learning strategies by students and teachers of the Associate degree in English and the English Teaching major from a public university campus in the southern region of Costa Rica. Based upon the findings derived from the instruments administered, several conclusions can be drawn.

First, although students and teachers seem to be very aware of the use of metacognitive strategies, there are some categories of this type that still need reinforcement such as centering your learning, delaying speech production to focus on listening, and evaluating your learning. In this regard, there are some practices that might facilitate language learning and teaching by the implementation of those strategies. Regarding the first category, there must be conscious practice on how to maximize the students’ attention in class to excel in various aspects of the language. Besides learning how to focus students’ full attention and activate their prior knowledge, the results suggest that students might benefit from practicing how to listen attentively, process the information, and keep repeating it silently until they feel ready to produce an utterance. Reviewing a topic every time it is introduced or practiced is a strategy that demands attention as well. Furthermore, it is recommended for students to learn how to activate their prior knowledge to link new data to the already existing. This strategy might help internalize and store information by strengthening students’ long-term memory.

In a similar vein, among all metacognitive strategy categories, the one that needs the most reinforcement is delaying speech production to focus on listening. The results of this study indicate that students might benefit from activating their inner speech so that when they listen to something and do not feel ready to speak, they repeat it silently to themselves. Inner speech, as a mental resource, has proven to be effective for outer speech (De Bleser & Marshall, 2005). On the benefits of using inner speech, Tomlinson (2012) pointed out that learners “use the inner voice to give their own voice to what they hear and read, to make plans, to make decisions, to solve problems, to evaluate, to understand and "control" their environment, and to prepare outer voice utterances before saying or writing them” (p. 91). Another activity suggested to enhance this metacognitive strategy is imitation. As learners watch and listen to an iconic person speak, (e.g., Barack Obama), they repeat each word in their minds and try to replicate pronunciation, intonation, speed, fluency, etc. Then, once they finish, they try to recreate what they remember from that person’s speech. It is advisable for students to learn how to center their attention on specific linguistic features they must correct. This is recommended since it may be an appropriate way to maximize their listening comprehension as they develop confidence and feel empowered to speak. It is worth noting that listening is developed faster than speaking, which tends to be threatening to most students.

The second strategy that teachers encourage students to practice more is the group of metacognitive strategies. Unlike students, among the different categories of this group, evaluating your learning is the least promoted strategy by teachers. Indeed, the subcategory related to this group self-evaluating, or measuring the overall language progress or achievements in one of the four language skills is the least strategy boosted by teachers. As a matter of fact, it is surprising that, although one of the types of assessments suggested in EFL is self-assessment besides peer and teacher assessment, it is not commonly promoted in these groups of learners. Oftentimes, students seem not to self-regulate their own learning. In this regard, orientation towards how to use the indirect learning strategies is essential to the learning process. Concerning the metacognitive strategies, teachers may find it useful to guide students towards a more self-directed language learning process. Learners might be given the tools to self-evaluate and measure their language progress and achievements by using checklists, diaries, journals, memoirs, and portfolios. These didactic resources may maximize language learning as they activate the constant use of the language inside and outside the EFL classroom. Keeping evidence of language progress may help students visualize their weaknesses and strengths, empower them to work on what is plausible to change and improve, and set goals and alternatives for their overall academic achievement.

Second, the analysis of the results indicates that the following categories of social strategies require some reinforcement on the students’ and teachers’ part: empathizing with others, becoming aware of others’ thoughts and feelings and developing cultural understanding by providing learners with knowledge of the new culture. It is worth stating several practices that may guarantee an effective use of these categories to improve language performance and academic goals. Regarding the first category, being an interlocutor involves more than exchanging words, ideas, and thoughts; it implies connecting with the other interlocutors to make sense out of the conversation and get meaning. In this regard, when students are guided, they are most likely to become aware of the other speakers’ opinions and emotions by examining their behavior in face-to-face interaction, and assessing tone, expression, and physical signals. Once again, they could learn how to listen carefully to what is being transmitted; when it comes to writing, learners might learn how to understand both literal and figurative meanings, as well as in speaking. By doing this, teachers might foster awareness-raising activities regarding the speakers’ thoughts, tone, mood and implied meanings in the classroom in order to promote assertive communication and decrease misunderstandings.

Concerning the second category of these social strategies, becoming aware of others’ thoughts and feelings, in order to develop more sensitivity towards others’ thoughts and feelings in students, observation might facilitate their understanding of these nonverbal signs or paralinguistic elements. It is recommended to have students watch one of their favorite programs and analyze the speakers’ tone, expressions, and physical signals in general. They may use a checklist to link any of these signals to what the speaker is facing at the moment. This may teach students to recognize these physical signals in action. The results of this study suggest that teachers would benefit from integrating this practice on empathy by using cultural capsules that portray specific instances of cross-cultural misunderstandings due to an improper interpretation of the other person’s behavior or feelings. Also, the Slice-of-Strategy (Chastain, 1988, as cited in Karam, 2017) might be replicated in the classroom. This strategy implies a short highlight or segment of life from the target culture presented at the very beginning of the class in the form of a video, song, or written post to trigger ideas and thoughts about the target culture. Eventually, cultural understanding could be broadened and cleansed from bias, stereotypes, or prejudices if teachers commit to these types of practices in the EFL classroom.

Another aspect that deserves attention is the strategy developing cultural understanding by providing learners with knowledge of the new culture. Although students of this study are taught two different courses on culture during their studies, cultural awareness seems to be a crucial aspect needing reinforcement during classes. Students need to dig deeper into the cultural content of the target culture. This may be achieved by means of introducing and practicing awareness-building cultural tidbits, activities and techniques along with the main content or subject matter of the courses. Furthermore, in order to sensitize students about cultural differences, students can be encouraged to watch series and videos representative of the target culture to highlight possible sources of cultural misunderstanding. This practice, when replicated and included in a language learning routine, may awaken a deeper engagement, curiosity, creativity, and reflection on the students’ part.

Third, the results suggest an overlooked use and enhancement of affective strategies by students as well as by teachers, respectively. In this respect, a set of ideas might facilitate the incorporation of the least used and activated categories of the affective strategies taking your emotional temperature and writing a diary. This might confirm the need to introduce emotional intelligence competences and affective strategies and techniques into the ordinary and traditional way of teaching and learning. In effect, taking your emotional temperature was the least practiced category of this group. Within the subcategories, writing a Diary seems to be a strategy not often used. Its benefits to improve the teaching and learning process seem to have been downplayed. This technique may favor students’ learning in multiple ways. Students’ self-awareness and self-understanding is practiced through the writing of daily entries or short reflections, which may boost students’ self-directed learning at a high level. Another benefit gained from this strategy is the enhancement of writing as students are required to put ideas down on paper and come up with the vocabulary needed to express their thoughts clearly. A diary may aid students’ memorization since the language when written is personalized and tends to linger in the students’ memories. Moreover, most learners may be more prone to practice the language that has been adjusted to their level through the personalized examples included in their diaries, for instance.

The findings of the study suggest that neither teachers nor students often reflect upon the use of diaries, checklists, or memoirs and use them to become self-aware of their emotions. On this account, the affective domain seems to be neglected in the activities and strategies that teachers encourage as effective practices to maximize the teaching and learning of the language. Not only are learners’ metacognitive strategies promoted using diaries, journals, memoirs, and other reflection tools but also their affective strategies. Once teachers become interested in the use of journals, reaction papers, diary entries and memoirs and realize their multiple benefits, they might connect students’ affect to their cognition since both feelings, states of mood, and language areas are activated.

Students might explore their feelings and become aware of their moods and behaviors according to the different tasks in every course as they write about the experience on a daily basis. Furthermore, these reflection tools as emotional enablers may contribute to the students’ learning process in various ways. First, as students recognize their feelings and emotional states when they perform a task, these enablers can help dilute affective barriers and lower the affective filter, resulting in a discovery and comprehension of the state where students can perform at their best. Second, these emotional enablers may guarantee students’ emotional maturity as they advance academically, impacting both their personal and professional lives. In fact, this finding sheds light upon the need to turn language instruction into a more affective and emotion-based process. Grounded on the main findings of this study, it is worth noting that the role of language instructors could comprise different ways to connect emotion with cognition to accelerate the learning process. This could be done by the intervention of teachers with appropriate tactics to impact students during their learning process.

Fourth, as teachers provide multiple opportunities for students to expand their repertoire of indirect learning strategies, learners may increase their willingness to take actions and control of their practices to maximize and accelerate effective language learning. This conscience and feel for self-regulation that teachers can awaken in students may lead to a sense of autonomy and agency. “Agentic students” know who they are and to what direction they are going. Little et al. (2002) threw light upon the concept of agentic students by sustaining that they are “the origin of their actions, have high aspirations, persevere in the face of obstacles, see more and varied options for action, learn from failures, and overall, have a greater sense of well-being” (390).

Fifth, although these revealing findings are only generalizable to the population surveyed, the results might open a window for discussion and reflection on how teachers promote the use of indirect learning strategies to help students achieve learning outcomes more effectively.

Sixth, the results of this study might sway teachers to design and launch different activities for EFL learners in and beyond the classroom as they might orient L2 instruction and open room for a possible change in strategy training.

Seventh, this is just a preliminary study on the application of indirect learning strategies according to university students’ language performance. It is expected to deepen the meaningfulness of this study by conducting further research on the implementation of a proposal based on the recommendations highlighted in this paper.

All in all, in the view of many scholars, there is a significant gap between the use of direct and indirect learning strategies. The results of this preliminary case study indicate the lack of use and enhancement of most of the categories of the indirect learning strategies, mainly of the affective ones. Thus, to foster a more comprehensive and balanced approach to language teaching and learning as suggested in the literature, the results of this study seem to signal a missing link in language success—the incorporation of affective strategies alongside of the practices accomplished by students and promoted by teachers in and beyond the classroom. Although there seems not to be a prescribed recipe to lead students to language success right away, the results of this study might be a wake-up call for teachers to strengthen the indirect learning strategies that have been neglected and downplayed in the EFL learning process. It is expected that not only teachers but also students could become more aware of the relevance of these strategies to optimize and succeed in the mastery of English as a foreign language.

References

Allwright, D. (1990). Autonomy in Language Pedagogy. CRILE Working Paper 6. University of Lancaster.

Blumberg, P. (2009). Developing learner-centered teaching: A practical guide for faculty. Jossey-Bass.

Cano de Araúz, O. (2009). Language learning strategies and its implication for second language teaching. Revista de Lenguas Modernas, 11(1), 399-411. https://revistas.ucr.ac.cr/index.php/rlm/article/view/9454/8904

Chamot, A. U. (1998). Teaching learning language strategies to language students. [EDOFL-025-976]. ERIC Clearinghouse on Language and Linguistics: [ED433719].

Cullen, R., Harris, M., & Hill, R. R. (2012). The learner-centered curriculum: Design and Implementation. Jossey-Bass.

De Bleser, R. ,& Marshall, J. M. (2005). Egon Weigl and the concept of inner speech. Cortex, 41(2), 249-257. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0010-9452(08)70910-9

Dreyer, C. & Oxford, R L. .(1996). Learning strategies and other predictors of ESL proficiency among Afrikaans-speakers in South Africa. In R. L. Oxford (Ed.), Language learning strategies around the world: Cross-cultural perspectives (pp. 61-74). University of Hawaii Press.

Ehrman, M. & Oxford, R. (1990). Adult language learning styles and strategies in an intensive training setting. The Modern Language Journal, 74(3), 311-326. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1990.tb01069.x

Erdogan, T. (2018). The investigation of self-regulation and language learning strategies. Universal Journal of Educational Research, 6(7), 1477-1485. https://doi.org/10.13189/ujer.2018.060708

Gall, M. D., Gall, J. P., & Borg, W. R. (2007). Educational research: An introduction (8th ed.). Pearson.

Giang, B. T. K., & Tuan, V. V. (2018). Language learning strategies of Vietnamese EFL freshmen. Arab World English Journal, 9(3), 61-83. https://dx.doi.org/10.24093/awej/vol9no3.5

Geng, G., Smith, P., Black, P., Budd, Y., & Disney, L. (2019). Reflective practice in teaching: Pre-service teachers and the lens of life. Springer Nature.

Goetzke, E. (2019, 20 March, 2019). Why don’t students use effective learning strategies?—A reflection. A TILE Talk Reflection.https://learningspaces.dundee.ac.uk/tile/2019/03/20/reflection-dr-flavia-schechtman-belhams-talk-on-why-dont-students-use-effective-learning-strategies

Hismanoglu, M. (2000, August). Language learning strategies in foreign language learning and teaching. The Internet TESL Journal. http://iteslj.org/Articles/Hismanoglu-Strategies.html

Karam, H., & Fatin, A. (2017). Teaching culture strategies in EFL classroom. ResearchGate. https://www.researchgate.net/publication/330337967_Teaching_Culture_Strategies_in_EFL_Classroom/references

Lessard-Clouston, M. (1997). Language learning strategies: An overview for L2 teachers. The Internet TESL Journal, 12(3). http://iteslj.org/Articles/Lessard-Clouston-Strategy.html

Little, D. (1991). Learner autonomy 1: Definitions, issues, and problems. Authentik.

Little, T. D., Hawley, P. H., Henrich, C. C., & Marsland, K. W. (2002). Three views of the agentic self: A developmental synthesis. In E. L. Deci, & R. M. Ryan (Eds.), Handbook of self-determination research (pp. 389-404). University of Rochester Press.

Nilson, L., & Zimmerman, B. J. (2013). Creating self-regulated learners: Strategies to strengthen students’ self-awareness and learning skills [Kindle]. https://www.amazon.com/Creating-Self-Regulated-Learners-Strategies-Self-Awareness-ebook/dp/B015YFJBFU/ref=tmm_kin_swatch_0?_encoding=UTF8&qid=&sr=

Nunan, D. (1999). Second language teaching and learning. Heinle and Heinle

Oxford, R. L. (1990). Language learning strategies: What every teacher should know. Newbury House.

Oxford, R. L. (2001). Language learning styles and strategies: An overview. ResearchGate https://www.researchgate.net/publication/254446824_Language_learning_styles_and_strategies_An_overview

Oxford, R.L., Judd, C., & Giesen, J. (1998). Relationships among learning strategies, learning styles, EFL proficiency, and academic performance among secondary school students in Turkey [Unpublished manuscript] University of Alabama.

O’Leary, C. (2014). Developing autonomous language learners in HE: A social constructivist perspective. In G. Murray (Ed.), Social dimensions of autonomy in language learning (pp. 15-36). Palgrave.

Panzachi Heredia, D. A. R., & Luchini, P. L. (2015). On becoming a good English language learner: An exploratory case study. HOW, 22(1), 26-44. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.22.1.116

Philp, J. (2017). What do successful language learners and their teachers do? [Cambridge Papers in ELT series]. Cambridge University Press. https://www.cambridge.org/us/files/3115/7488/7366/CambridgePapersinELT_Successful_Learners_2017_ONLINE.pdf

Purpura, J. (1999). Learner characteristics and L2 test performance. In R. L. Oxford (Ed.), Language learning strategies in the context of autonomy: Synthesis of findings from the International Invitational Conference on Learning Strategy Research (pp. 61-63), Teachers College, Columbia University, New York, NY.

Ravitch, S. & Carl, N. M. (2016). Qualitative research: Bridging the conceptual, theoretical, and methodological. SAGE.

Rubin, J. (1975). What the good language learner can teach us. TESOL Quarterly 9, 41-51.

Rubin, J., & Thompson, I. (1982). How to become a more successful language learner. Heinle & Heinle.

Scarcella, R. C. & Oxford, R. L.(1992). The tapestry of language learning: The individual in the communicative classroom. Heinle & Heinle.

Simons, H. (2009). Case study research in practice. SAGE.

Shuy, T. (2010). Self-regulated learning [TESL Center Fact Sheet No. 3]. The Teaching Excellence in Adult Literacy (TEAL) Center. U.S. Department of Education. https://lincs.ed.gov/sites/default/files/3_TEAL_Self%20Reg%20Learning.pdf

Stage, F. K., Muller, P. A., Kinzie, J. & Simmons, A. (1998). Creating Learner Centered Classrooms: What Does Learning Theory Have to Say? (ED422778). ERIC. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED422778.pdf

Thomas, G. (2011). How to do your case study: A guide for students and researchers. SAGE..

Thompson, S. (2005). The “good language learner”. University of Birminham, TEFL/TESL Teaching. https://www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-artslaw/cels/essagys/secondlanguage/essayGLLSThompson.pdf

Tomlinson, B. (2012). Materials development for language learning and teaching. Language Teaching, 45(2), 143-179. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000528

Véliz C., M. (2012). Language learning strategies (LLSs) and L2 motivation associated with L2 pronunciation development in pre-service teachers of English. Literatura y Lingüística, (25), 193-220. https://doi.org/10.4067/S0716-58112012000100010

Weimer, M. (2002). Learner-centered teaching: Five key changes to practice. Jossey-Bass.

Wolters, C. (2015, n.d.). Strategies for building self-regulated learning. University Center for the Advancement of Teaching, The Ohio State University. https://ucat.osu.edu/blog/strategies-for-building-self-regulated-learning-by-dr-chris-wolters

Wong, L. L. C., & Nunan, D. (2011). The learning styles and strategies of effective language learners. System, 39(2), 144-163. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2011.05.004

Wright, G. B. (2011). Student-centered learning in higher education. International Journal of Teaching and Learning in Higher Education, 23(3), 92-97. http://www.isetl.org/ijtlhe/articleView.cfm?id=834