Introduction

In many countries around the world, English language is viewed as the language of progress at both the individual and national levels. Mansoor (2003), Rahman (2002) and Tacelosky (2018) affirm that the use of English could provide people who know the language with a source of self-improvement and as a means to pursue professional success. Therefore, English can assist people to achieve their personal goals and social mobility in the long term. Esch (2009) explains that empowerment emerges when people become aware of the importance of learning English as a tool to access progress and knowledge and go into further learning. Through English, people may obtain access to new forms of knowledge, which can benefit not only the individual but also society in different ways. In addition to this, one of the benefits of learning a foreign language refers to opening people’s minds to different types of information regarding culture or specific knowledge available in that language.

The study examined the perceptions that a group of first semester female students had about studying in an English language teaching (ELT) undergraduate program, as well as their views on their personal and professional self-development through learning English.

Education for All

There is a global trend to offer the same opportunities for women and men; however, the United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (UNESCO) (2019a) in their report on Gender Equity affirms that discrimination and biases against women pursuing education still exist. The persistence of discrimination in social institutions inevitably permeates education systems, including a subtle agreement of what may be acceptable for the genders and their roles, such as going to college and getting involved in a professional career. UNESCO (2019b) has highlighted the significance of investing in education for women as it can empower them to go into leadership roles and set up ways to achieve their economic independence. However, this awareness has not been easy to attain. In the past, women tended to be excluded from participation in many types of formal education. However, they have recently constituted the largest proportion and most rapidly growing cohort of participants in many educational settings, particularly in higher education (Hayes & Flannery, 2000; Leathwood & Read 2008; United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization, 2016). In Mexico, even with the growing number of women attending college, young women, especially in small communities, still face many challenges in their purpose to attend college.

Access to college, however, does not guarantee success and many female college students never achieve their educational goals for various reasons including discrimination. Ellis et al. (2006) defined gender discrimination as the exclusions or restrictions made on the basis of the socially constructed gender roles based on what is acceptable for each one of the sexes in different fields of study. Additionally, Mickelson (2003) found that discrimination “arises from actions of institutions or individual state actors, their attitudes and ideologies” (p.1052) which seems to be the source of gender treatment differences. For example, encouraging boys to continue studying and go to college, and on the other side, persuading girls not to pursue higher studies. The following sections will, then, explore the backgrounds and perspectives of the participants in order to explain the importance of the research.

Family and Education for Women in Mexico

Family has been considered the main and most valuable element of the Mexican culture. González-Hernández (2011) states that the most important moral values in Mexican families are safety, unity, trust, and commitment. Traditionally, women act as the unifying element for Mexican families. The construction of the family concept in Mexico brings generations together and tries to preserve its value by the close interaction among family members.

In addition to the fact that women are the main caretakers of children and elders in most communities around the world, they must also develop different skills and knowledge if they want financial independence within their communities. Despite the increasing number of women attending school in Mexico, (Mingo, 2016; Parker & Pederzini, 2000), significant differences are still evident between the genders in relation to education. Parker and Pederzini (2000) stated that “…parents are still more reluctant to send their daughters to schools that are not close by or require substantially more walking than their sons” (p. 41). This supports the fact that women in Mexico still suffer discrimination and an overload of work even within their family nucleus, when they are not allowed to go to school or college because parents want them to stay nearby or because they must help with house chores.

Women at Work

In some contexts, such as Mexico where the current study was carried out, discrimination against women often starts at birth. Gender roles are established by society and exclusions for women continue throughout their lives. These gender constructs emphasize their lack of skills and capacity and these beliefs may lead to the false stereotype that women do not belong in the corporate world. Discrimination against women may also begin in childhood as young girls can be brought up to believe that they are only suited for certain professions or, in some cases, only to serve as wives and mothers, as Zabludovsky (2007) established and Parker and Pederzini (2000) found in their study carried out in Mexico.

Sohaib et al. (2012) have argued that the subordinate position of women in society is common around the world. Although this position of subordination is somewhat attenuated in higher social classes, discrimination against women has still several subtle manifestations in women’s daily life. Women have the almost exclusive responsibility for family and children, which might result in narrowing their career aspirations and a low self-esteem. However, and in spite of all the challenges women have faced through history, in different areas of their lives, this sector of the world’s population seems to record the greatest success in achieving a higher income and becoming entrepreneurs. To exemplify this claim, the UNESCO (2016), in its report about gender inequality in education, reported that almost 50% of the human capital and business owners are women.

In Mexico, according to the Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo (ENOE)[1] women composed 60% of the informal employment sector during 2018-2019 (Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía, 2020). This survey also showed that inequity still exists with regards to the salary women and men receive in the same job positions since women receive 17% less in comparison to their male peers. Additionally, women in Mexico suffer a higher percentage of unemployment. Therefore, it is evident that there is still a need for action in order to lessen the injustices that prevail in the job market in Mexico.

Empowerment

In order to start talking about empowerment, it is necessary to define the term. Brunson and Vogt (1996) described empowerment as a growth process of an individual supported and encouraged by a community or a group structure that promotes learning. Once the definition has been established, it is also relevant to define what an empowered person does. According to Ashcroft (1987) the empowered individual is “someone who believes in his or her ability/capability to act, and this belief would be accompanied by action” (p. 143). Individual empowerment might develop when people attempt to overcome obstacles and attain self-determination and mastery, as Boehm and Staples (as cited in Hur, 2006) state regarding the individual aspect of empowerment. Within a process of empowerment, the concept of agency is relevant. Gao (2011) defined agency as the individual’s will and capacity to take actions following a system of beliefs and motivation. Agency might then precede a process of empowerment, when individuals embark on a journey of education.

In relation to education and particularly within the field of teaching and learning English, Norton and Toohey (2001) have argued that learners are willing to invest in a second language, as they believe it might increase their social value. Language can be used to evidence empowerment as a tool to exercise the role gained by an empowered person. By the same token, Hussain et al. (2009) have explained that people can control how they participate in society through the use of language or by learning a foreign language. Therefore, learning English can be a tool for empowerment and might help people widen their opportunities in life, for example, by expanding their employability skills and achieve social mobility resulting in a more satisfactory life, such as in Norton’s(1995) concepts of capital and intellectual investment. In other words, language-empowered individuals have more access to various forms of capital (linguistic, social, cultural) and are more capable of playing a significant role in their communities of practice by maximizing the role of code switching as Wang and Mansouri (2017) identified.

From this point of view, empowerment seems to be about changing society. It is about obtaining knowledge and understanding of the functionality of society which will allow people, female students as in the case of this study, to transform the conditions of their own life and the lives of the ones around them. However, as Ashcroft (1987) mentioned, empowerment can be personal or social, activated by the examination of fundamental beliefs, sometimes triggered by other actors in the community.

By interacting with others within a community, individuals may identify their own selves and build their identities. Norton (2013) has defined identity as “the way a person understands his or her relationship to the world, how that relationship is constructed across time and space, and how the person understands possibilities for the future” (p. 4), just as the process through which the participants of the study transformed their identities and perceptions. Before a professional identify emerges, individuals might develop a personal identity based on their past contexts and the relationships they have established with other members of their communities.

Role Models

A role model is, according to Pleiss and Feldhusen (1995), a person who is perceived by others as worthy of imitation. Role models can be family members, teachers or a recognized person in the community who can affect a person’s experiences, self-esteem, and educational or occupational outcomes. However, Bamberger (2014) found that people are more likely to choose a profession when they identify a role model within the field of knowledge in which they are interested and to whom they can feel related given the context or situation in which they find themselves.

According to Scales et al. (2001), the most important function of the role model is to model attitudes, values, and behavior that a person may find significant and integrate them into their own life. Lookwood (2006) found that successful role models should be of similar age, gender and ethnic group in order to be more effective. Teachers can also take the role of supportive figures and role models, especially when they were not satisfied with the conditions of their jobs due to salaries or workload (British Council, 2017) and take actions according to the figures or role models they admire. However, for women who want to start higher education, finding a role model can be difficult.

The Current Study

For example, in Mexico, some female students are the first women in the generations within their communities or families who dare to challenge the traditional roles, as some of the participants of this research expressed. The researchers analyzed college women’s empowerment process to determine how their roles are conceptualized and developed, as well as the way they construct their perspectives towards a better future by acquiring the English language and college education. The participants’ perceptions were explored through analyzing two narratives students wrote at two different moments of their first semester. Connelly and Clandinin (1990) argued that humans tell stories when they talk about their experiences. Narrative inquiry allows the study of how humans experience the world through the collection of stories. In order to achieve the objective of exploring the experiences of a group of female college students during their first semester of an ELT program, two research questions were developed:

- What are the perceptions and expectations of a group of female college students about learning English during their first semester in an ELT program?

- What are the main factors that influence the participants´ process of empowerment through English learning according to the participants’ narratives?

The answers to these questions might generate knowledge on women empowerment and English learning in female students when they start studying a major in ELT in a Mexican public university.

Methodology

Research Design

In this qualitative study, narrative inquiry is adopted as a research design. As stated in Lieblich et al. (1998), using the narrative inquiry approach enables researchers “to understand the inner or subjective world of the person, how he or she thinks about her own experience, situation, problems, life…”( p. 172) which were the topics that the researchers aimed to explore. The study relied on what Norton and Early (2011) have called the “small stories” that participants share with researchers in order to establish their “self”. Connelly and Clandinin (2006) established that a story might be “a portal through which a person enters the world and by which their experience of the world is interpreted and made personally meaningful” (p. 375), exploring aspects of the lives of the participants as one of the objectives of the study, justified the use of narrative inquiry.

Regarding the process of learning English, Johnson (2006) claimed that looking into language teaching from a sociocultural point of view could define “human learning as a dynamic social activity” (p. 237). The stories of participants allow researchers to explore the social and cultural conditions in which they develop such narratives. Additionally, Etherington (2004) explained that through narratives, researchers systematically gather, analyze, and represent people’s stories as they are told and that these stories might challenge traditional and modern views on reality, knowledge and identity. Therefore, narrative inquiry seemed the most suitable methodology to elicit the participants’ perspectives through “small stories” they told about themselves.

Context of the Research

This research was conducted in the School of Languages of a public university in Mexico, the Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla (BUAP) in Mexico. The School of Languages offers a BA and an MA in English Language Teaching (ELT). As a public university, most of the students come from middle to lower economic classes due to the fact that in Mexico students in public universities, do not have to pay a tuition for their college studies. Puebla is a central state in Mexico, the capital, Puebla is the fourth most populated city in the country, and although some international industries have established their affiliate companies there, some of the poorest areas in the country are located in the state, especially in small towns in the mountains or Sierra de Puebla.

Students come from all backgrounds and even from other surrounding states. During the first semester of the ELT majors, groups include 15 to 25 students and female students compose approximately 70% of the population.

Participants

The participants in this research were twelve female students from a public university in Mexico. The participants were from different backgrounds, seven of the participants were from urban contexts and five came from rural localities. These rural participants had to move to the city in order to study a major. Most of the participants came from low economic homes, especially the ones coming from rural contexts where their families were either farmers or small business owners, like one of the participants who mentioned that the family business was the production of handicrafts and they themselves sold their products in the local market. Therefore, some of these students needed to find a job in the city in order to pay their living and college expenses.

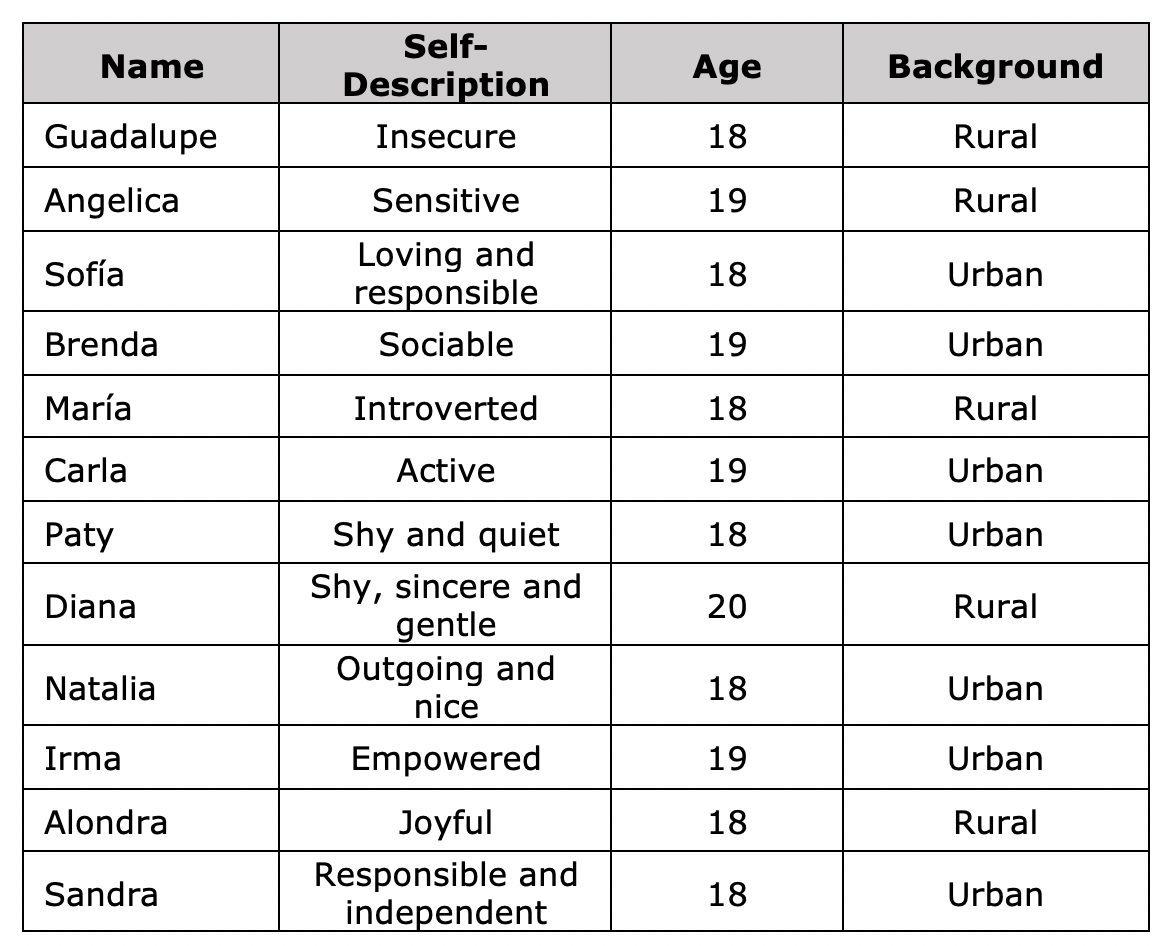

In relation to language, eleven of the participants spoke Spanish as their first language and one of them spoke an indigenous language (Nahuatl) as her first language. The average age of the participants was 18 years old at the moment of the study. All of them went through an admission process in order to start their studies in college, which included a general knowledge exam and a language fluency interview. As part of the initial narrative, the participants were asked to describe themselves; Table 1 presents the names (pseudonyms), the adjectives the participants used in their self- descriptions, their ages and their backgrounds:

Table 1: The participants

Instruments

Two instruments were developed as the means to gather the information in order to answer the research questions established for the study. The first instrument, the initial narrative was written at the beginning of the term, in August of 2018. The participants were asked to write an autobiographical narrative, as suggested by Jaatinen (2007). In consequence, the participants wrote their narratives which described their previous experiences giving details of their hometown, educational background and the family values. They also mentioned the people who had supported them in the pursuit of education, the people who have made an impact in their life as well as the most relevant decisions they have made, their personality, and the expectations they had by studying an ELT program. Through their narratives, the participants allowed the researchers to contextualize the backgrounds and the backgrounds of the group of female students when they started their major.

Second Instrument: Empowerment Narrative

The second narrative was written at the end of the term, in December of 2018. The participants were asked to write about their experiences during their first semester in college; the narratives followed the guidelines given by Mellita and Cholil (2012). These authors have identified several factors as helpful motivators that contribute to generate successful female narratives. The participants were given the following hints to write their narrative: challenges and opportunities for self-fulfillment, education and qualification, support from the family members and others, independent decision-making, employment status and innovative thinking.

Both narratives were written in the classroom during their English classes. The participants wrote their narratives or “small stories” in Spanish and their words were translated into English.

Data Analysis Process

Once the data was collected, key words were identified in order to find similarities or differences among the narratives. That is, categories were identified by using thematic analysis which has been defined as “A method for identifying, analyzing and reporting patterns within data.” according to Braun and Clarke (2006, p. 79). Then, the patterns found in both narratives provided the basis for a generalization of results, which could represent what female students experienced in their first semester in college in the context of the study, but could also be transferred to other contexts.

Subsequently, after reading the data provided, we realized that the participants had divided their experiences in three stages, their past (what happened before coming to college), the present (their situation when they started college), and the future (the expectations they had for their own lives).

Therefore, in order to analyze all the information, the following steps were developed by the researchers:

- Once the two sets of narratives were gathered, the recordings were transcribed and different categories were identified.

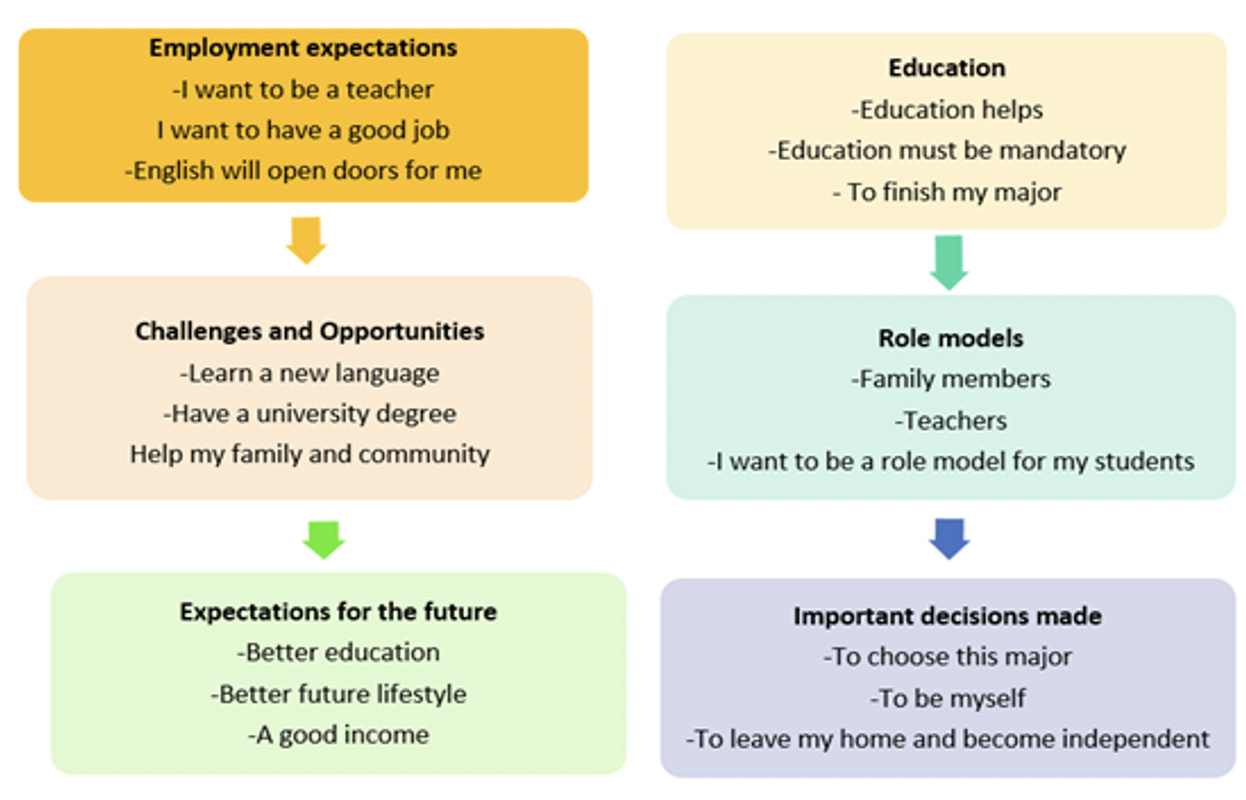

- Then, the information was classified under the different categories identified in the first narrative (See Fig. 1).

- After transcribing and analyzing the information of participants, a timeline for each participant was created to share the stages that participants went through as part of their personal and professional development. The timelines started in the past, with the decisions that participants had made and the role models who had inspired them. The present was represented by how these female students described themselves as well as their backgrounds in order to understand their origins and their situation when they started college. The future was expressed by means of the expectations they developed about their personal and professional future in their “small stories”.

- Finally, the results were presented in two stages (initial and second narratives) in order to highlight the difference in the scope of the answers given by the participants. The results of the initial narrative were summarized in a chart and three individual timelines would illustrate the results from the second narrative.

Results from the Initial Narrative

The data from the initial narrative, written at the beginning of the participants’ first semester of their college education, was organized in the categories identified from the participants’ comments: employment expectations, education, challenges and opportunities, role models, and important decisions and expectations for the future. Figure 1 shows a summary of some of the recurrent comments made by the participants corresponding to the different categories. The comments were repeated at least three times to be included in the chart.

Figure 1: Results from the initial narrative

According to their narratives, at the beginning of their first semester in college, the participants were aware and sometimes proud of the decisions they had made to pursue higher education. Some of the participants had to challenge “the traditional perspectives” that their families and communities held for women, for example, “by being the first woman in her family to go to college” as María said. Additionally, one of the participants explained that she had to “be herself which can be explained as to make her own decisions”, that is, exercising her agency (Gao, 2011) in order to continue with her studies, as not everybody in her family supported her idea to go to college. Another relevant issue mentioned by four of the participants was that one of the most important decisions they had made was to leave home and start the ELT major as they came from rural or distant locations.

Six participants mentioned that they were influenced by their role models in order to make the decision to undertake higher education. Interestingly, six of the participants wrote that they were the first ones to study a bachelors’ degree in their family. Two of them mentioned that their mothers had been a great influence as they encouraged these young women to pursue their studies; another two mentioned their teachers as their role models, and one of them said that she wanted to be an “example” for her future students.

All participants were aware of the importance of education; they explained that education for them meant, “…to finish a major” and two of them affirmed that education should be mandatory for everybody. Most of these pre-service female teachers explained that having the opportunity to study for a B.A. in ELT could mean a better future for their families as well as for themselves. However, some of the challenges the participants mentioned were “to learn a new language, to have a university degree and to grow personally and professionally.” The categories identified showed that when participants started their college studies, they were aware of the benefits of studying a major and, as a result, they were full of expectations regarding their studies and their future.

Results from the Second Narrative

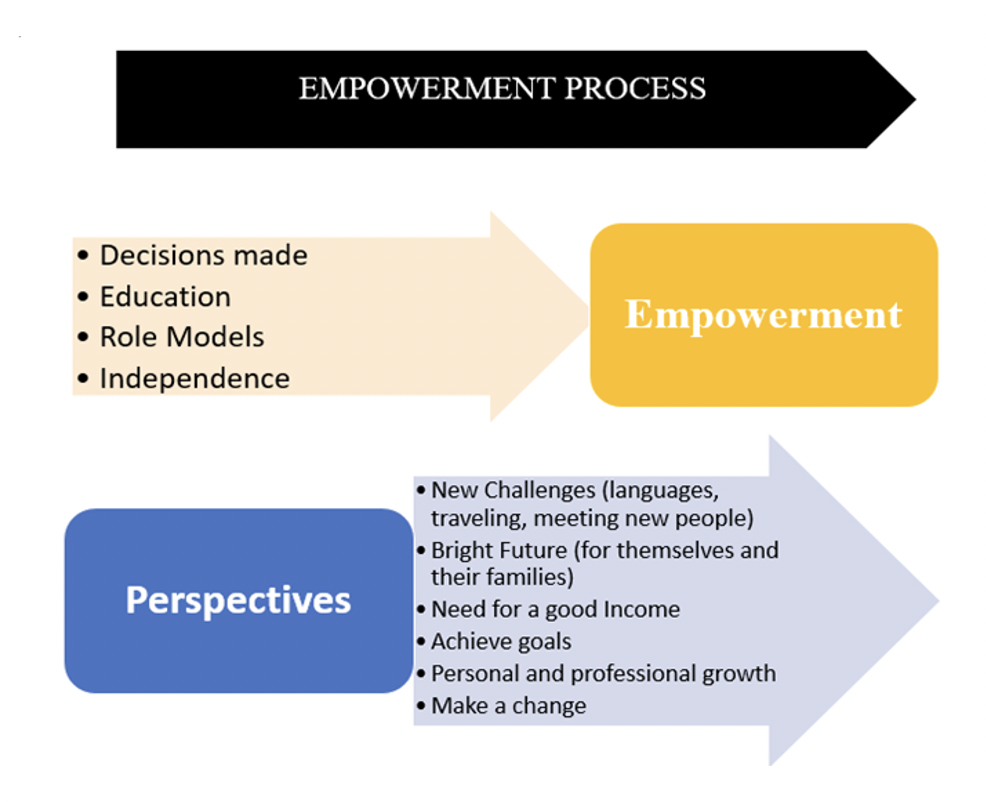

After collecting and analyzing the second narrative at the end of the semester, it was evident that the tone of the discourse of the participants had changed. These narratives showed that the perspectives of the participants regarding their education had broadened the scope of their own personal and professional growth. That is why it was called “the empowerment narrative”. Figure 2 shows the way participants’ perspectives and views had widened and how they felt empowered to achieve their goals.

Figure 2: The empowerment narratives

Timelines

Once both narratives were analyzed, three moments in the process of empowerment of the participants emerged. First, the present, which was represented by the person they were at the beginning of their first semester in college. The decisions they had made before they started their college education and the support they had received to make those decisions became the past. Finally, the future was the participants’ perspectives and expectations they had at the end of the semester, and the way they felt empowered to achieve their goals and make a change in their lives and the lives of the ones around them. As Norton and Early (2011) claimed, the “small stories” provided a way to present their identities and to conceptualize participants’ roles in the two moments of the study and allowed the organization of the data in timelines. According to Barry (1997), timelines allow to contextualize information, facilitate detailed information activities and identify changes in the behaviors of individuals.

Additionally, following de Lange, et al. (2007) who said that visual representations enhance inquiry and illustrate participant perspectives, a timeline was created for each one of the participant. For this article, three timelines are presented as a sample of the participants’ development and empowerment stages reported in their narratives. The timelines also served as the framework for the discussion of the results, allowing the researchers to answer the questions posed to guide the study.

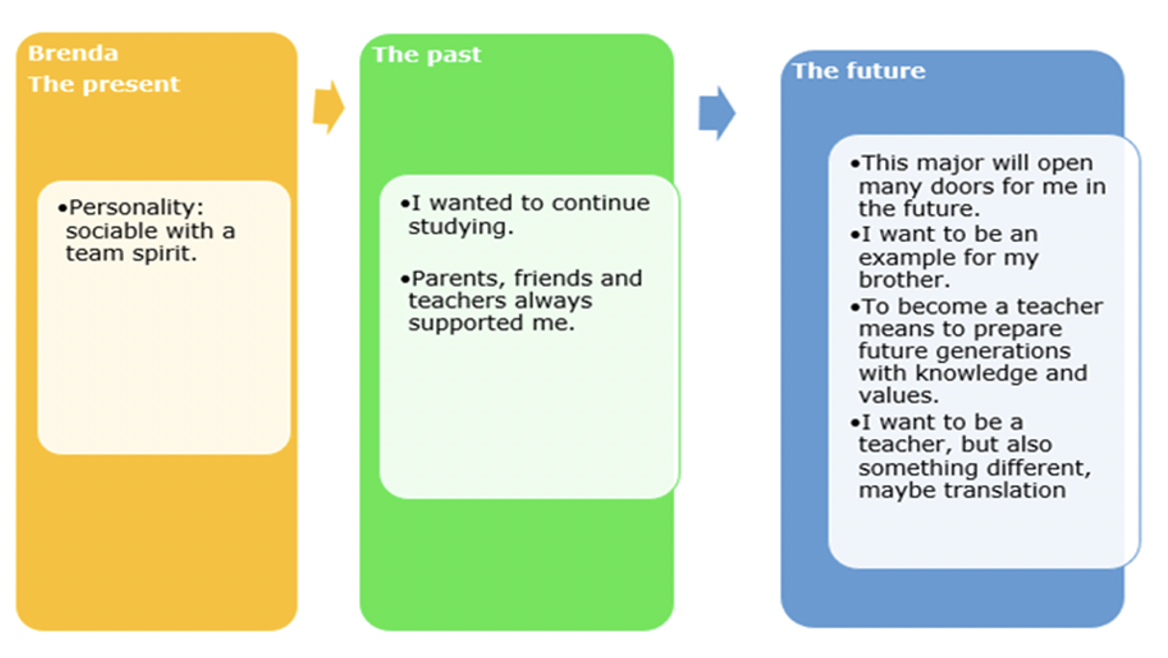

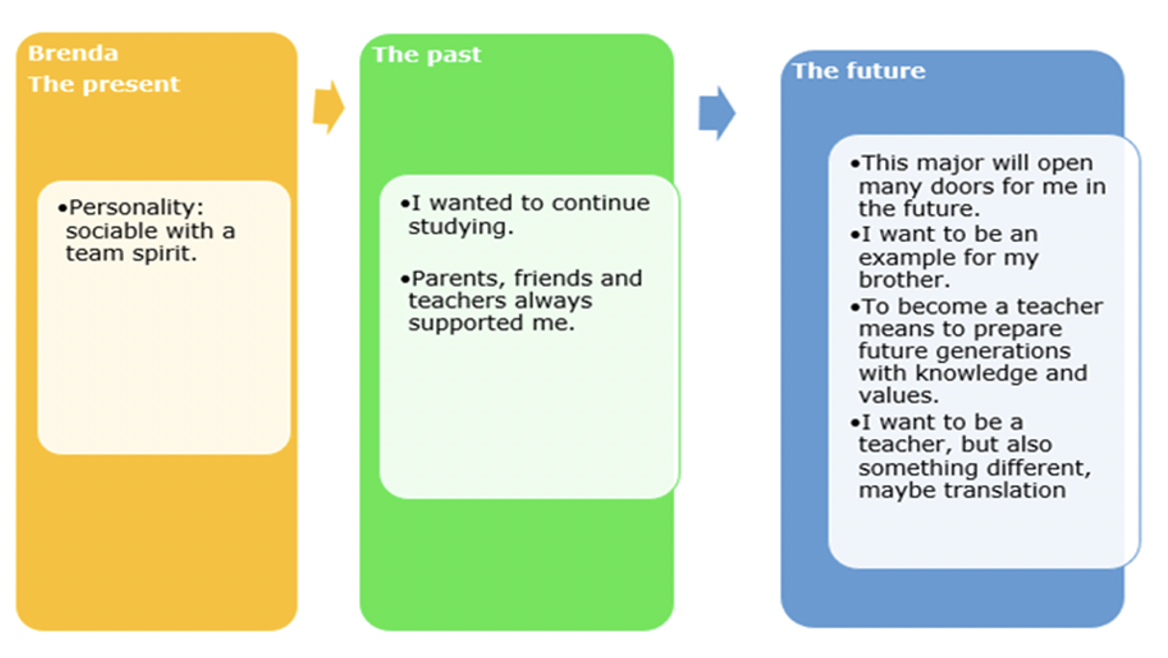

Brenda’sTimeline

Brenda described herself as a sociable girl with a positive attitude towards people. In the initial narrative, Brenda shared that her family nucleus had always been supportive and although her parents had not pursued higher education, they were happy about her studies. Then, with the support of her family, Brenda started an EFL major in a public university. Fig. 3 shows Brenda’s timeline with the information gathered from the second narrative. Her words evidenced that she had developed broader perspectives for herself, her future teaching career and her family during the semester.

Figure 3: Brenda’s timeline

Maria’s Timeline

The second timeline is Maria’s. At the beginning of the semester, she described herself as an introverted girl. She also shared that some family members were her role models as they had pursued a professional career, for example, her father was an architect.

It is worth it to mention that in the empowerment narrative, Brenda explained that she wanted to become “a woman that can do everything through communicating in different languages” which might not correspond with her previous description of an “introverted girl,” as she referred to herself in the initial narrative. She even mentioned that she wanted to go abroad for an exchange program. Maria’s narratives evidenced the personal and academic development she had experienced throughout the semester.

Figure 4: Maria’s timeline

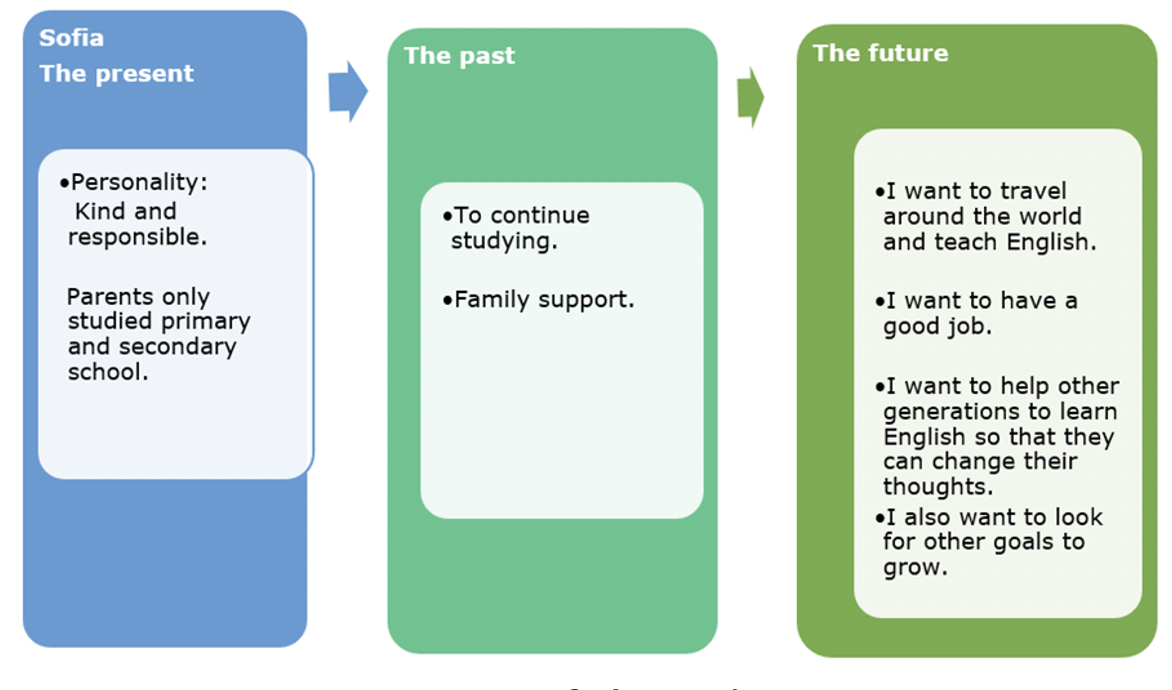

Sofia’s Timeline

Initially, Sofia referred to herself as a kind and responsible girl who wanted to achieve her goals. She mentioned that her parents had only studied elementary school, but for them education was an important value in the family. She also referred to her aunts and her parents as supportive figures in her pursuit of higher education. Sofia, then, had a support network who facilitated her college entry. At the end of the semester, Sofia wrote that she wanted to travel around the world and she believed that she could do so by teaching English. Additionally, she mentioned that she wanted to inspire younger generations to learn English in order to change her thinking probably because that was something she did along the semester. Sofia gave evidence that English and education can empower students and that a female empowered student can take control of her actions and lead a functional and fulfilling life as Sullivan (2002) has claimed.

Figure 5: Sofia’s timeline

From the examples of these three timelines and the results presented, it was evident that the participants’ perceptions, goals and perspectives had broaden during their first semester in college. By going to college and learning English in an ELT program, the participants went through personal and academic processes of development and empowerment, sometimes with their family support, especially from female members, or by expanding their views on their personal goals and dreams.

In the beginning of their initial semester of an ELT program, participants perceived that learning English was a challenge and they knew that undertaking and finishing a degree was not going to be an easy enterprise. However, the participants had high expectations regarding their future which according to their own statements could be bright and better. All the participants expected that higher-education would improve their lives and the lives of their families. It is also important to mention that the participants expected to earn a good income when they started working. The participants affirmed that by learning English they could also achieve other goals such as traveling and working or studying abroad. The participants’ small stories have also raised awareness on the importance of creating support nets, which can be composed of teachers, relatives or peers, for female college students in order to encourage them to gain self-confidence to pursue their goals for higher education.

Conclusions

The key findings emphasize the importance of role models and a support net as significant factors which can lead women to an empowerment process through education. The participants agreed that by learning and teaching the language, they can achieve their goals, become role models for their families or communities, inspire new generations and change the minds of their future learners. The decisions they had made before going to college, the knowledge they had acquired and the experiences lived during their first semester empowered them to be better prepared to achieve their personal and professional goals.

Learning a foreign language allows people to communicate worldwide. Speaking or teaching English meant independence as it might make a woman eligible to obtain university scholarships or to apply to better job opportunities that might lead college female students to personal and financial independence, just as the participants claimed.

The study has given evidence that female college students rely on family support, but are also able to challenge some traditional views on education that might remain in the family nucleus. Making the right decisions may lead female students pursue higher education and make them more likely to succeed in their studies and achieve their personal and academic goals. Finally, female empowerment might develop gender-egalitarian awareness and attitudes among the members of the society who can see what language learning and education can do for women.

References

Ashcroft, L. (1987). Defusing "empowering": The what and the why. Language Arts, 64(2), 142-156. https://www.jstor.org/stable/41961588

Bamberger, Y. M. (2014). Encouraging girls into science and technology with feminine role model: Does this work? Journal of Science Education and Technology, 23(4), 549–561. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10956-014-9487-7

Barry, C. A. (1997). The research activity timeline: A qualitative tool for information research. Library & Information Science Research.19(2). 153-179. https://doi.org/10.1016/S0740-8188(97)90041-4

Braun, V., & Clarke, V. (2006). Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qualitative Research in Psychology, 3, 77-101.https://doi.org/10.1191/1478088706qp063oa

British Council. (2017). Empowering girls and women through education. https://www.britishcouncil.org/sites/default/files/empowering_women_and_girls_through_education.pdf

Brunson, D. A., & Vogt, J. V. (1996). Empowering our students and ourselves: A liberal democratic approach to the communication classroom. Communication Education, 45(1), 73-83. https://doi.org/10.1080/03634529609379033

Connelly, F. M. & Clandinin, D. J. (1990) Stories of experience and narrative inquiry. Educational. Researcher, 19(5). https://doi.org/10.3102%2F0013189X019005002

Connelly, F. M., & Clandinin, D. J. (2006). Narrative inquiry. In J. L. Green, G. Camilli, & P. Elmore (Eds.), Handbook of complementary methods in education research (3rd ed., pp. 477-487). Lawrence Erlbaum.

de Lange, N., Mitchell, C., & Stuart, J. (Eds.) (2007). Putting people in the picture. Visual methodologies for social change. Sense.

Ellis, D. M. Meeker, B. J., & Hyde, B. L. (2006). Exploring men’s perceived educational experiences in a baccalaureate program. Journal of Nursing Education, 45(12), 523-527. https://doi.org/10.3928/01484834-20061201-09

Esch, E. (2009). English and empowerment: Potentials, issues, way forward. In Hussain, N., Ahmed, A., & Zafar, M. (Eds.). English and empowerment in the developing world. (pp 2-26). Cambridge Scholars.

Etherington, K. (2004) Becoming a reflexive researcher: Using ourselves in research. Jessica Kingsley.

González-Hernández, I. (2011). La familia mexicana en la era de la información globalizada [The Mexican family in the globalized information era]. Revista Mexicana de Opinión Pública, 10, 203-218. http://dx.doi.org/10.22201/fcpys.24484911e.2011.10.41784

Gao, F. (2011). Exploring the reconstruction of Chinese learners’ national identities in their English-language-learning journeys in Britain.Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 10(5). 287-305. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2011.614543

Hayes, E., & Flannery, D. D. (2000). Women as learners: The significance of gender in adult learning. Jossey-Bass.

Hussain N., Ahmed A., & Zafar M., (Eds., 2009). English and empowerment in the developing world. Cambridge Scholars.

Hur, M. H. (2006). Empowerment in terms of theoretical perspectives: Exploring a typology of the process and components across disciplines. Journal of Community Psychology, 34(5), 523-540. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.20113

Instituto Nacional de Estadística y Geografía (2020, 13 February). Resultados de la Encuesta Nacional de Ocupación y Empleo (ENOE): Cifras durante el cuarto trimestre de 2019. [Results of the National Occupation and Employment survey: Figures during the first quarter, 2019]. INEGI. https://www.inegi.org.mx/contenidos/saladeprensa/boletines/2020/enoe_ie/enoe_ie2020_02.pdf

Jaatinen, R. (2007). Learning languages, learning life-skills: Autobiographical reflexive approach to teaching and learning a foreign language. Springer.

Johnson, K. E. (2006). The sociocultural turn and its challenges for second language teacher education. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1), 235–257. https://doi.org/10.2307/40264518

Leathwood, C., & Read, B. (2008). Gender and the changing face of higher education: A feminized future? A feminized future? McGraw-Hill Education.

Lieblich, A., Liybliyk, A., Tuval-Mashiach, R., & Zilber, T. (1998). Narrative research: Reading, analysis and interpretation. Sage.

Lookwood, P. (2006). “Someone like me can be successful”: Do college students need same-gender role models? Psychology of Women Quarterly, 30(1), 36-46. https://doi.org/10.1111%2Fj.1471-6402.2006.00260.x

Mansoor, S. (2003). Language planning in higher education: Issues of access and equity.’ Lahore Journal of Economics, 8(2), 17–42. https://doi.org/10.35536/lje.2003.v8.i2.a2

Mellita, D., & Cholil, W. (2012). ECommerce and women empowerment: Challenge for women-owned small business in developing country. International Conference on Business Management and IS, 1(1). http://www.ijacp.org/ojs/index.php/ICBMIS/article/view/44/50

Mickelson, R. A. (2003). When are racial disparities in education the result of racial discrimination? A social science perspective. Teachers College Record, 105(6), 1052-1086. https://www.tcrecord.org/Content.asp?ContentId=11548

Mingo, A. (2016). "¡Pasen a borrar el pizarrón!" Mujeres en la universidad. [“Come clean the board!” Women in the university]. Revista de la educación superior, 45(178), 1-15. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.resu.2016.03.001

Norton, B. & Early, M. (2011). Researcher identity, narrative inquiry, and language teaching research. TESOL Quarterly, 45(3), 415-439. https://doi.org/10.5054/tq.2011.261161

Norton, B., & Toohey, K. (2011). Identity, language learning, and social change. Language Teaching, 44(4), 412-446. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000309

Norton, B. (2013). Identity and language learning: Extending the conversation. Multilingual Matters.

Parker, S. W., & Pederzini, C. (2002). Diferencias de género en la educación en México [Gender differences in education in Mexico]. In E. G. Katz & M. C. Correia, (Eds.), La economía de género en México: Trabajo, familia, Estado y mercado. Nacional Financiera.http://documents.worldbank.org/curated/en/153261468278741735/pdf/222420PUB00SPA00Box0361520B0PUBLIC0.pdf

Peirce, B. N. (1995). Social identity, investment, and language learning. TESOL Quarterly, 29(1), 9-31. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587803

Pleiss, M. K., & Feldhusen, J. F. (1995). Mentors, role models, and heroes in the lives of gifted children. Educational Psychologist, 30(3), 159–169. https://doi.org/10.1207/s15326985ep3003_6

Rahman, T. (2005). Passports to privilege: The English-medium schools in Pakistan. Peace and Democracy in South Asia, 1(1), 24–44. http://himalaya.socanth.cam.ac.uk/collections/journals/pdsa/pdf/pdsa_01_01_04.pdf

Scales, P. C., Benson, P. L., Roehlkepartain, E. C., Hintz, N. R., Sullivan, T. K., & Mannes, M. (2001). The role of neighborhood and community in building developmental assets for children and youth: A national study of social norms among American adults. Journal of Community Psychology, 29(6), 703–727. https://doi.org/10.1002/jcop.1044

Shoaib, M., Saeed, Y. & Cheema, S. N. (2012). Education and women’s empowerment at household Level: A case study of women in rural Chiniot, Pakistan. Academic Research International. 2(1), 490-518. http://www.savap.org.pk/journals/ARInt./Vol.2(1)/2012(2.1-51).pdf

Sullivan, A. M. (2002). Student empowerment in a primary school classroom: A descriptive study [Unpublished doctoral dissertation], Edith Cowan University. https://ro.ecu.edu.au/theses/1068

Tacelosky, K. (2018). Teaching English to English speakers: The role of English Teachers in the school experience of transnational students in Mexico. MEXTESOL Journal, 42(3), 1-13. http://www.mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=3758

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization (2016). eAtlas of gender inequality in education. https://tellmaps.com/uis/gender/#!/tellmap/-1195952519

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2019a). UNESCO global education monitoring report: Gender report: Building bridges for gender equality. https://docplayer.net/156896280-Global-education-monitoring-report-gender-report-building-bridges-for-gender-equality.html

United Nations Educational, Scientific and Cultural Organization. (2019b). UN women: Annual report 2018-2019.https://annualreport.unwomen.org/en/2019

Wang, H., & Mansouri, B. (2017). Revisiting code-switching practice in TESOL: A critical perspective. Asia-Pacific Education Researcher. 26(6). 407–415. https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-017-0359-9

Zabludovsky, G. (2007). Las mujeres en México: trabajo, educación superior y esferas de poder. [Women in Mexico: Work, higher education and spheres of power]. Política y cultura, 28, 9-41. http://www.scielo.org.mx/scielo.php?script=sci_arttext&pid=S0188-77422007000200002

[1] National Occupation and Employment Survey