Introduction

The interaction between digital technologies and education generates debates, promises, and reservations among educational experts, particularly on the weight that should be assigned to technology in learning. Concerning this dialogue, Säljö (2010) asserts that, even when there is consensus that pedagogy, not technology, drives education, technology has affected the way in which human beings construct their experience of the world. As a response to this socio-educational imperative, educational systems around the world have implemented different programmes aided by technology.

In Uruguay, Plan Ceibal[1]was created in 2007 (Kaiser, 2017) as an ambitious nation-wide project to reduce the digital divide and provide learners with equal opportunities and inclusion mediated through technology. Plan Ceibal provides every learner with a laptop computer and free connectivity at public schools to facilitate meaningful learning. To achieve this aim, the project also creates programmes, resources, and professional development opportunities for teachers. Plan Ceibal generates educational opportunities on a wide range of school subjects, and one of them is English language learning under the project called Ceibal en Inglés (Banegas 2013; Kaiser, 2017).

Ceibal en Inglés[2](CEI) has been assessed as a success story in what we may call technology-enhanced language learning (Carrier, Cameron, & Bailey, 2017; Hockly, 2017, Walker & White, 2013) since its implementation in 2012. Built around videoconferencing and with the support of the British Council, the programme has expanded from providing English language learning to 1,000 primary school learners (Banegas, 2013) to reaching around 80,000 primary school learners and 17,000 secondary school learners (Brovetto, 2017; Kaiser, 2017).

The aim of this article is to explore and evaluate the development of this innovative practice in English language teaching in Uruguayan primary and secondary education through four areas: (1) English language learning, (2) motivation, (3) teacher professional development, and (4) the interplay between technology-mediated learning and face-to-face learning.

Ceibal en Inglés

Primary School

When Ceibal en Inglés (CEI) was born in 2012, it sought to promote social justice by making English language teaching accessible to primary school learners in different regions of Uruguay. English is only taught in secondary education and therefore the programme aims at making English language learning accessible from primary education. CEI is designed on the basis of three components: remote teaching, collaborative team teaching, and blended learning (Brovetto, 2017; Kaplan & Brovetto, 2019). According to Banegas (2013), the programme sought to “demonstrate that lessons delivered by remote teachers (RTs) via videoconferencing with support from classroom teachers (CTs) with little command of English can facilitate successful learning outcomes in learners, including effective interaction with the RT, CT and between learners”(p. 180).

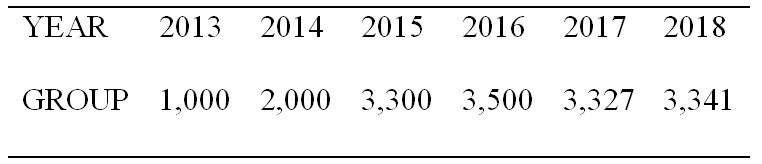

In a review of language practice and policy in Uruguay, Brovetto (2017) explains that the lack of qualified teachers of English prompted the pedagogical model in place through blended teaching mediated by videoconferencing and learners’ laptop computers. In CEI in primary education, a Spanish-speaking primary classroom teacher located in the classroom works collaboratively with a remote teacher of English to provide learners with three English lessons a week. Stanley (2015) details that while in the first lesson (Lesson A) the RT leads language presentation, the CT is in charge of classroom management and the other two lessons (Lessons B and C) are led solely by the CT who facilitates language practice until the following lesson through videoconferencing. Lesson A-C are delivered in a single week over an entire school year (March-November). On average, the learners have lessons with the RT 32 times a year. The programme provides teachers with lesson plans, teaching materials, and professional support for language proficiency and language pedagogy. In terms of figures, the programme in primary education has enjoyed a steady increase making the universalisation of English language learning in grades 4 to 6 a possible enterprise. As Kaiser (2017) describes, the programme started with 48 primary groups/classes in 2012, and then expanded as shown in Table 1 reaching 74,739 children in 3,341 groups (Kaplan & Brovetto, 2019). In the context of CEI, the term ‘group’ equals ‘class’.

Table 1. Number of primary school groups (2013-2018)

Figures have fluctuated due to a drop in the number of groups or learners in general education or thecreation of EFL teaching posts. Thus, some groups of learners may leave CEI but still continue to receive English language learning provision.

Secondary School

In 2014, the programme moved beyond primary education and was implemented in secondary schools, where English is an established subject. In this case, the programme entails the remote presence of English-speaking language teachers who focus on oral skills and intercultural understanding as a response to demands and weaknesses detected by secondary English language teachers. In secondary education, the programme is called Conversation Classes. Kaplan and Brovetto (2019) explain that when a classroom English language teacher ‘signs up for this, one of the three curricular hours of English includes the participation of an RT, who is usually a native speaker of English, and who co-conducts – together with the classroom teacher of English (CTE) – a lesson that focuses on promoting oral skills and multicultural awareness’ (46-47). It is interesting to observe, from an evaluative stance, that native-speaker teachers seem to be preferred. This feature of the programme may inadvertently undermine non-native teachers’ linguistic confidence to carry out successful speaking lessons and reinforce the often-criticised native-non-native dichotomy.

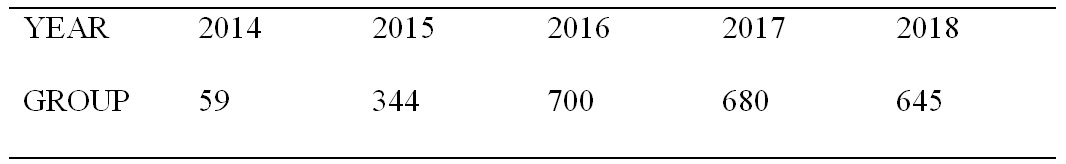

According to recent figures, the Conversation Classes programme has reached around 17,000 teenagers (Kaiser, 2017; Kaplan & Brovetto, 2019). However, it has experienced a slow decline since it started in 2014 (See Table 2) due to a number of reasons, among which we can mention teachers’ insufficient time availability for programme participation and practical constraints such as booking the school videoconferencing room in advance, or connectivity problems. These reasons should be regarded as warnings toPlan Ceibal en Inglés project managers since lack of programme participation may mask other reasons that demotivate secondary school EFL teachers and gives way to embrace Conversation Classes. One of such reasons, we speculate, is the possible CT’s perception that the native RT will be assessed as a more capable and professional educator in the learners’ eyes.

Table 2. Number of secondary school groups (2014-2018)

English Language Learning under Ceibal en Inglés

CEI defines itself as a communicative language teaching, learner-centered programme. The curriculum and lesson plans promote the development of the four language skills, but emphasises listening and speaking.

The programme includes the implementation of an annual evaluation of learners’ progress through an adaptive on-line test. In the initial stages of the project the goal was to determine if the combined design resulted in significant learning. In further stages, up to the present, the adaptive test has gone through continuous revision to provide information at the system, classroom and individual levels. At the level of the system, the adaptive on-line test provides valuable aggregated data of a large learner population participating in different English teaching programmes in both primary and secondary schools. At the level of the classroom, teachers are able to use the results of this national test as part of their evaluation strategies. Finally, the test provides information at the individual level, since learners access their results through a digital platform.

The test was originally designed by a specialised group formed by the British Council and local specialists in Uruguay in 2014, and it is aligned with the Common European Framework. It has five main components: Vocabulary, reading, grammar, listening (multiple choice adaptive tests) and writing (on-line, non-adaptive). A Speaking component is currently under design. The whole test is currently in a process of validation by the Center for Research in English Language Learning and Assessment, of the University of Bedfordshire. It should be noted that the test is designed and implemented by CEI staff and CTs and RTs do not have active involvement in its development. They are only implementers and therefore, their agency as teachers is somehow reduced to implementing lessons and tests designed by other stakeholders and consultants. This may be regarded as a drawback in teacher agency and development as their participation in decision making processes is limited.

The results have shown continuous improvement in the performance of the learners, with a consistent growth that correlates with the permanence in the programme. The analysis of the results has also shown that children participating in CEI obtain similar results as children in the face-to-face programme (Marconi & Brovetto, 2019). In the last edition of the test, about 80% of the students of Ceibal en Inglés in grade 6 (third year of participation in the programme) reached A2 level in the Vocabulary-Grammar component of the test, and 68% of the students reached this level in the Listening component (Marconi & Brovetto, 2019). However, for careful and exhaustive programme evaluation, the test should include all language skills in a manner that respects the unique characteristics of individual groups to incorporate formative and process assessment.

Motivation

We adopt a relational view of language learning motivation (Ushioda, 2009). In line with this view, motivation is a multifaceted, dynamic, and unstable construct which responds to the environmental interactions between people and their context. In the multimodal and technology-enhanced classroom that Ceibal en Inglés creates, the relational view of motivation that Ushioda proposes does not only reach the context, but also the synergy created between learners and teachers. As Pinner (2019) points out, in the interaction between learners and teachers there is an exchange of energy which is mutually enriching and necessary for meaningful knowledge construction. The literature documenting CEI has problematised and provided sobering evidence in support of the role that the programme plays among learners and teachers regarding the interplay between motivation and language education.

Stanley (2015) points out that CEI materials and activities are engaging, attractive, and are changed regularly. The author notes that the use of videoconferencing acts as a motivational drive provided the use of high quality and reliable connectivity and equipment. Stanley adds that the possibility of intercultural interaction among classroom teachers, remote teachers and learners has become a source of motivation and engagement as collaborative work and team teaching does not only affect classroom life and professional development but also personal understanding and intercultural experiences.

Classroom teacher motivation is paramount to ensure programme success. According to Stanley (2017), classroom teacher motivation hinges on systematic communication with, and support from, the remote teacher since subject-matter expertise is often exhibited as a source of demotivation among classroom teachers. Drawing on evidence, the author points out that when classroom teachers are less engaged in the project, only those learners who are already motivated to learn English for personal reasons show higher participation and motivation levels.

Regarding teacher and learner motivation, Ramírez (2019), a classroom teacher, carried out a teacher-research based study with her group of learners. The teacher had noticed that although the remote teacher used interactive and multimedia-based tasks and the learners would exhibit a positive attitude, their motivation would decrease after a while. By means of questionnaires and classroom observation notes, the author found that the following factors contributed to learner demotivation: learners’ shyness to speak in class, fear of making mistakes, and the teachers’ own unclear participation in Lesson A as well as her insecurities for leading Lessons B and C. Other crucial factors were technological issues which reduced the possibility of using the digital materials included in each lesson. The teacher reacted to these factors and noted a rise in her own and learners’ motivation when she exercised her agency by selecting and creating her own activities.

Drawing on the teachers’ classroom research gathered in Kaplan (2019), learners’ motivation is enhanced when they are engaged in Lesson A with the remote teacher because that presence is less familiar. Games, music, or video-based activities are sources of learner motivation together with group activities or activities that promote intercultural understanding. Conversely, oral presentations in front of the remote and/or the classroom teacher are a source of anxiety, frustration, or demotivation. A similar behaviour is exhibited when the teachers translate the activities to Spanish without allowing sufficient time for learners’ autonomous understanding or thinking time for activity solving.

While the focus is often placed on the learners and the classroom teacher, there has been interest in understanding remote teachers’ motivation. For example, Chatfield (2019) compared remote teaching centres for the programme and observed that although both classroom and remote teachers need motivating support, remote teachers lack instant feedback from the learners or colleagues. In the case of remote teachers, feedback is channeled through post-lesson learner comments, body language and overheard conversations provided there is good internet connectivity.

In general, it is reasonable to make the claim that, while videoconferencing and the presence of a remote teacher does contribute to learner motivation, the sources of motivation and demotivation among learners and teachers do not differ from face-to-face environments as the reasons behind (de)motivation are connected to autonomy, agency, and other affective factors present in any human interaction. Future studies in this area should include longitudinal studies which examine the correlation between motivation and technology-enhanced language learning and teaching through theoretical models which consider the synergy between learners and both classroom and remote teachers.

Teacher Professional Development

For technology in education to prove successful, teacher professional development is paramount. In a qualitative study on technology integration, Gönen (2019) reminds us that there must be professional support and guidance so that teachers understand the many facets of language learning with technology not only at practical level but also at more theoretical degrees of understanding.

Since its inception, CEI has sought to position regular classroom teachers, particularly in primary education, as co-constructors of new knowledge and facilitators of language learning experiences in tandem with the remote teachers, who are specialised in English language teaching. Given the heightened importance of teacher development, CEI supports both classroom as well as remote teachers since team teaching and collaboration lie at the heart of the project.

With regard to classroom teachers and their professional development, Kaplan (2019) explains that classroom teachers in CEI boost their development through three interrelated areas: (1) English language development by taking a self-access course, (2) reflection and collaboration through negotiations with remote teachers, and (3) pedagogy since through (1) and (2) they can expand their horizons and incorporate digital tools and transform other areas of the curriculum. While the three areas are central, reports tend to focus on the interactional contours behind the programme. For example, Stanley (2015) describes the orientation sessions that classroom teachers receive at the beginning of each iteration of the programme where the roles that classroom and remote teachers are expected to have are explained. They also explore the online platform where teaching materials and lesson plans are stored and the self-access course for their English language learning. Kaplan and Brovetto (2019) and Rovegno (2019) add that classroom teachers also receive support in lesson planning, team teaching and collaboration strategies as the project unfolds through mentoring.

However, stories of success are not without its challenges concerning team teaching. In a critical study carried out with both classroom and remote teachers, Fradi (2017, 2018) found substantial variations among team teaching practices as a result of lack of alignment between classroom and remote teachers’ roles in practice and the roles envisaged by CEI programme developers. In particular, it has been found that there is some variation in the way classroom teachers implement the revision and consolidation lessons (lessons B and C) (Kaiser, 2017). According to the original design of the program, classroom teachers are expected to facilitate two 45-minute lessons for revision and consolidation of the linguistic content introduced by the remote teacher in lesson A. In a series of observations and interviews conducted by Kaiser, he found that some teachers facilitate only one of these sessions, others conduct shorter sessions, while some teachers do not include these lessons at all. There are lesson plans that determine the content of lessons B and C; however, not all teachers follow these lesson plans. These might lead to a revision of the very structure of the programme to make it more aligned with the reality of its implementation.

Remote teachers are also engaged in professional development. For example, De los Santos (2015) describes a series of training sessions through which remote teachers discuss the differences between face-to-face and videoconferencing teaching and deepen their knowledge around three aspects: (1) bonding with children through videoconferencing, (2) sharing class leadership with the classroom teacher, and (3) maximising language input, practice, and production. Other professional development opportunities involve engaging remote teachers in action research (Rovegno & Pintos, 2017), surveying the teaching and professional skills that remote teachers think they need to have (Pintos, 2019), and implementing peer observation between remote teachers at the different remote teaching centres employed by Ceibal en Inglés (Cardoso, 2019). All these initiatives, the authors highlight, aim at building authentic knowledge-sharing communities of practice supported through specialised and peer mentoring. While the professional development initiatives implemented are to be praised, they exhibit a tendency to be organised or run by language educators who are not based in the context where CEI takes place. CEI, thus, should design professional development courses that capitalise local knowledge production.

Interplay between Technology-mediated Learning and Face-to-face Learning

CEI has always co-existed with a face-to-face programme called Segundas Lenguas[3]that started in the 90s with a small group of schools and has not been able to expand significantly due to the shortage of teachers and the high demand of qualified English lessons inside and beyond formal education. Both programmes—CEI and Segundas Lenguas —have divided the groups of 4 to 6 grades so that approximately 70% are covered by CEI and 30% by Segundas Lenguas. In the last couple of years, however, a few schools were able to get face-to-face teachers moved from CEI to Segundas Lenguas.

It has to be pointed out, however, that CEI´s foundational feature as a compensatory programme has evolved with time to give place to a more comprehensive series of programmes that combine technology and pedagogy to support and enhance the ELT classroom. Diverse modalities of CEI are implemented depending on the needs and conditions of teachers and students.

The Conversation Class programme presented above, which is implemented in secondary education, for example, combines the expertise of two teachers of English, one in the classroom, and another one who works remotely through videoconference. In this project the RT provides more real-life opportunities to use English through intercultural interactions. Other modalities implemented in the last two years are the Tutorials for Differentiated Learning (TDL) in secondary schools, designed to cater for the different levels of proficiency in English providing differentiated activities online through the program´s LMS, and Make it Happen (MIH), implemented in a groups of primary schools attended by underprivileged children who require closer attention and where teachers demand stronger support. Nonetheless, these initiatives still need careful evaluation to measure impact among the target learners.

Conclusion

We must consider the challenges that Ceibal en Inglés faces for the future from different perspectives: from the pedagogical and technical perspective, as well as its sustainability as a language policy. From the pedagogical point of view, it can be claimed that the benefits of remote and collaborative teaching, and the blended teaching design seem to be well established as proven teaching strategies in the field of ELT and education in general (Carrier et al., 2017; Säljö, 2010). Among other possible solutions, CEI has implemented one that crucially relies on the possibility of teachers collaborating in the distance and taking complementary pedagogical roles for the benefit of their students. Although the programme is still young, it could be said that the new role that CEI offers to teachers – both, the remote and the classroom teachers - has a positive impact on the teacher’s self-perception, and constitutes in itself an opportunity for professional development with impact on the general practice of these teachers beyond the specific programme, as shown in some of the testimonies gathered by Kaplan (2019). From the technological perspective, the accessibility of stable and strong connectivity and the quality of the telepresence is likely to keep improving in the future. This requires however, the investment in support and maintenance, as well as the allocation of resources at the national level for research and development in the relevant areas, as well as the relevant articulation between educational and technological goals.

As a language policy, the possible dependence of the programme on the availability of foreign teachers of English needs further consideration. Differently from a regular face-to-face classroom organised with local teachers, and precisely because of the lack of enough qualified teachers, CEI requires recruitment of teachers outside the country. To address this challenge, CEI has agreements with a wide range of institutions - English language academies - based in Uruguay and abroad, where the British Council plays a crucial role. The curriculum, materials and lesson plans are centrally provided and the programme includes a centralised system for teacher support and quality management. Notwithstanding, the CEI programme and universalisation of English language teaching in Uruguay should depend less on international outsourcing and work towards pre-service and in-service English language teaching preparation possibly employing the same resources that CEI affords. In this sense, implementing online or blended-learning initial language teacher education could be a viable option. In addition to teacher preparation, further work on local knowledge production and context-responsive pedagogies in the hands of Uruguay-based teachers should be sought in order to minimise seeing CTs and RTs as mere programme (lessons and tests) implementers. CEI support should allow teachers, learners, and other stakeholders to exercise full agency and engagement.

References

Banegas, D. L. (2013). ELT through videoconferencing in primary schools in Uruguay: First steps. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 7(2),179-188. https://doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2013.794803

Brovetto, C. (2017). Language policy and language practice in Uruguay: A case of innovation in English language teaching in primary schools. In L. D. Kamhi-Stein, G. Díaz Maggioli and L. C. de Oliveira (Eds.),English language teaching in South America: Policy, preparation and practices (pp. 54-74). Multilingual Matters.

Cardoso, W. (2019). Peer observation for remote teacher development. In G. Stanley (Ed.), Innovations in education: Remote teaching (pp. 87-90). British Council. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/innovations-education-remote-teaching

Carrier, M., Cameron, R. M., & Bailey, K. M. (Eds.). (2017). Digital language learning and teaching: Research, theory, and practice. Routledge.

Chatfield, R. (2019). Management of a remote teaching centre. In G. Stanley (Ed.), Innovations in education: Remote teaching (pp. 18-26). British Council. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/innovations-education-remote-teaching

De los Santos, A. (2015). Teaching English to young learners through videoconferencing: Possibilities and restrictions. Colección Digital Fundación Ceibal. https://digital.fundacionceibal.edu.uy/jspui/handle/123456789/156

Frade, V. (2017). Interacción y roles en las clases de Ceibal en Inglés: Estudio de una propuesta educativa que busca ser innovadora [Interaction and roles in the Ceibal en Inglés: Study of an educational proposal that hopes to be innovative] (Unpublished master’s thesis). Universidad de la República, Uruguay. https://www.academia.edu/Documents/in/Ceibal_en_Ingl%C3%A9s

Frade, V. (2018). (Des)construcción de la identidad docente: Estudio de caso de enseñanza de inglés por videoconferencia en Uruguay. [(De)construction of the teacher’s identity: A case study of English language teaching using videoconference in Uruguay], Linguagem & Ensino, 21 (Special Issue), 121-146. http://dx.doi.org/10.15210/rle.v21i0.15117

Gönen, S. I. K. (2019). A qualitative study on a situated experience of technology integration: Reflections from pre-service teachers and students. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 32(3) (163-189). https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2018.1552974

Hockly, N. (2017). One-to-one computer initiatives. ELT Journal, 71(1), 80-86. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccw077

Kaiser, D. J. (2017). English language teaching in Uruguay. World Englishes, 36(4), 744-759. https://doi.org/10.1111/weng.12261

Kaplan, G. (Ed.). (2019).Ceibal en inglés: La voz docente. Plan Ceibal.

Kaplan, G., & Brovetto, C. (2019). Ceibal en Inglés: Innovation, teamwork and technology. In G. Stanley (Ed.),Innovations in education: Remote teaching (pp. 28-35). British Council. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/innovations-education-remote-teaching

Marconi, C., & Brovetto, C. (2019). How evaluation and assessment are intrinsic to Ceibal en Inglés. In G. Stanley (Ed.), Innovations in education: Remote teaching (pp. 105-113). British Council. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/innovations-education-remote-teaching

Pinner, R. (2019). Authenticity and teacher-student motivational synergy: A narrative of language teaching. Routledge.

Pintos, V. (2019). What skills do Ceibal en Inglés remote teachers need? In G. Stanley (Ed.), Innovations in education: Remote teaching (pp. 43-50). British Council. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/innovations-education-remote-teaching

Ramírez, R. (2019). La motivación en las clases de inglés. [Motivation in English classes]. In G. Kaplan (Ed.), Ceibal en inglés: La voz docente [Ceibal in English: The teacher’s voice]. (pp. 54-59). Plan Ceibal.

Rovegno, S. (2019). The experience from the other side of the screen: Ceibal Classroom teachers. In G. Stanley (Ed.), Innovations in education: Remote teaching (pp. 61-65). British Council. https://www.teachingenglish.org.uk/article/innovations-education-remote-teaching

Rovegno, S., & Pintos, V. (2017). Building up authentic knowledge through teacher research. In D. L. Banegas, M. López-Barrios, M. Porto, & D. Waigandt (Eds.), Authenticity in ELT: Selected papers from the 42nd FAAPI Conference (pp. 10-21). APIM.

Säljö, R. (2010). Digital tools and challenges to institutional traditions of learning: Technologies, social memory and the performative nature of learning. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 26(1), 53-64. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1365-2729.2009.00341.x

Stanley, G. (2015). Plan Ceibal English: Remote teaching of primary school children in Uruguay through videoconferencing. In C. N. Giannikas, L. McLaughlin, G. Fanning, & N. D. Muller (Eds.), Children learning English: From research to practice(pp. 201-213). Garnet/IATEFL.

Stanley, G. (2017). Remote teaching: A case study of teaching primary school children English via videoconferencing in Uruguay. In M. Carrier, R. Damerow, & K. Bailey (Eds.), Digital language learning and teaching: Research, theory and practice (pp. 188-197). Routledge.

Ushioda, E. (2009). A person-in-context relational view of emergent motivation, self and identity. In Z. Dörnyei & E. Ushioda (Eds.),Motivation, language identity and the L2 self (pp. 215-228). Multilingual Matters.

Walker, W., & White, G. (2013). Technology-enhanced language learning: Connecting theory and practice. Oxford University Press.

[1] http://www.cep.edu.uy/2-principal/23-programas-segundas-lenguas