Introduction

Several scholars and commentators (Garton & Graves, 2014; Litz, 2005; Richards, 2001, 2014; Tomlinson, 2012) have reiterated the importance of EFL textbooks in language learning and instruction. In the same regard, Sheldon (1988), and Richards (1993) consider language learning materials as the “visible heart of any ELT programme” (p. 237) and “the hidden curriculum of ESL course” (p. 1) respectively. EFL textbooks generally consist of several sections of which one of the most important is reading. Reading can serve two purposes—for pleasure or for information (Ur, 1996). It has been considered as “an essential skill that individuals need to process in order to be successful in life”, which “keeps individuals informed, up-to-date and thinking” (Mckee, 2012, p.45). Reading plays a vital role in language learning, as well, according to Freeman (2014) and McDonough et al. (2013).

Comprehension questions as “one of the most frequent and time-honored activities” (Aebersold & Field, 1997, p.117) still exist in reading materials (Masuhara, 2013). They can make reading purposeful and “make the whole activity more interesting and effective” as well as help us to “know how well our learners are reading” (Ur, 1996, p.145). Furthermore, Anderson and Biddle (as cited in Grabe, 2009) posit that answering questions after reading improves comprehension for adults, which could subsequently lead to “appreciation of reading for both knowledge and pleasure” (Willis, 2008, p.127).

On the other hand, it has been argued that analyzing the content of textbooks would help teachers examine the textbooks critically acting as a guidance, which would develop teachers’ pedagogical decision-making in choosing suitable materials for their learners (Richards, 1993).

In the last two decades, Bloom’s (1956) original and revised taxonomy has been the framework of studies investigating the cognitive level of EFL materials. Bloom’s taxonomy consists of six levels: Knowledge, Comprehension, Application, Analysis, Synthesis and Evaluation. Tasks and questions which fall under the first three levels are less cognitively challenging while the next three levels demand higher cognitive abilities. The explanation of each level is given below.

Knowledge:The ability to recall specific information and universal concepts, methods, and processes.

Comprehension: A type of understanding such that the individual knows what is being communicated.

Application: The transfer of information or concepts discussed in one context to another context.

Analysis:The ability to see the organization of a communication and the relationships between ideas.

Synthesis: The ability to put together pieces in order to see a structure that was not obvious before.

Evaluation: Bloom (as cited in Aebersold & Field, 1997) defines it as the ability to consider and judge the value of the materials in a given context for a specific purpose.

One strand of research examining the content of EFL textbooks has focused on examining the extent to which the tasks and questions fall within higher or lower order skills (Adli & Mahmoudi, 2017; Birjandi & Alizadeh, 2013; Igbaria, 2013; Razmjoo & Kazempourfard, 2012; Roohani et al., 2014). For instance, Roohani et al., (2014(used Bloom’s revised taxonomy to analyze the cognitive level of Four Corners 2 and 3. The results were indicative of the dominance of activities which cognitively fell within the lower-order category. Razmjoo and Kazempourfard (2012) analyzed the Interchange series (2005) based on Bloom’s revised taxonomy. The results indicated that the content of Interchange did not foster higher order thinking skills.

In the same vein, based on Bloom’s taxonomy Adli and Mahmoudi (2017) investigated the reading comprehension questions incorporated in elementary and advanced levels of American Headway and Inside Reading. The results showed that both series mainly lent themselves to the lower cognitive skills. They also found that in two levels of proficiencies there were significant differences among question types except Analysis and Synthesis. Although the statistical tests revealed no significant difference between Analysis and Synthesis in two levels, based on the P test of Analysis type, which equals to 0.05, and its figure in the Mean Rank table, the authors identified a trend indicating the larger number of this type of questions in advanced level.

Although the above-mentioned studies have made useful contributions shedding light on the overall cognitive level of content of the EFL textbooks, with the exception of Adli and Mahmoudi’s (2017) very few of them have focused specifically on the reading comprehension questions and tasks. Besides, all the reading questions might not lend themselves to Bloom’s taxonomy since it “encompassed the wider, multi-disciplinary domain” and it was not created to specifically focus on the L2 reading context (Freeman, 2014, p.77).

On the other hand, there are some taxonomies focusing specifically on the reading materials, but these have attracted little attention on the part of researchers. For example, Nuttall (1996) suggested six types of questions for checking learners’ comprehension, which could also function as a taxonomy to evaluate the reading materials. Type 1 are questions of literal comprehension whose answers are directly and explicitly expressed in the text (p .188). Type 2 questions involve reorganization or reinterpretation. To answer this type of questions, learners need to reinterpret literal information or collate it from different parts of the text. Questions type 3 do not require students to quote answers verbatim from the text, but demand inferences, which increase the cognitive load required on the part of learners. Type 4 are questions of evaluation, which require learners to make considered judgments about “the writers’ honesty or bias” as well as “the force of her arguments” (p, 188). Type 5 are questions of personal response, which require learners to “record their reactions to the text” (p.189). Questions type 6 are concerned with how writers say what they mean, which aim to increase learners’ readiness in handling different texts with new words.

Day and Park (2005) proposed a taxonomy which consisted of six question types such as Literal, Reorganization, Inference, Prediction, Evaluation and Personal Response. To a great extent, it was similar to Nuttall’s (1996) framework. However, incorporating Prediction question type and omitting questions targeting reading strategies distinguished their framework from that of Nuttall (Freeman, 2014).

Quite recently, reviewing and trialing a number of existing taxonomies for analyzing reading comprehension questions, Freeman (2014) found that no single taxonomy covers all the reading comprehension questions and task types. To put it in her own words, “no single taxonomy proved to be wholly suitable and superior to its counterparts” (p. 77). Therefore, she combined the previous taxonomies, added some new categories, and came up with a more comprehensive one. Her taxonomy included three main types of questions: Content, Language and Affect types. Content questions, which “cover the information contained in the text (such as who, what, where, when, how)” (p.80), consist of Explicit, Implicit and Inferential categories “spanning lower to higher order thinking” (p.72). Language questions, which deal with “language-related tasks” (p.80), are comprised of three categories including Reorganization, Lexical and Form, which are not hierarchical. Affect question type “involves the learners responding to the text” (p.81) and is made up of Personal Response category, which falls within lower order thinking, and Evaluation category, which is more cognitively challenging. Descriptions of each category and type can be found in table 3 in the Appendix.

Freeman used her own taxonomy to investigate the post-reading comprehension questions and task types—henceforth called reading ‘comp-qs’—the abbreviation was taken from Freeman (2014)—in the first and at least two edited versions of four intermediate EFL textbook series named Headway (4 series), American File (2 series), Cutting Edge (2 series), and Inside Out (2 series). The results indicated the dominance of content questions in each series over the other categories, with Headway taking the lead in this regard. Another finding was that questions regarding Form mainly targeted lexical knowledge. This category was the most dominant in American File. Regarding the Affect type, questions requiring personal response were more prevalent than Evaluation category. This dominance was more significant in Inside Out.

Reviewing the studies above, we found that most of the studies have investigated cognitive levels of EFL materials based on Bloom’s taxonomy. However, to the best knowledge of the researchers, no study except Freeman’s (2014) has applied this taxonomy to reading sections of EFL materials. Besides, Freeman calls for further research to analyze the comprehension questions of the readings in textbooks of different proficiency levels. Therefore, reading comprehension questions and task types in EFL materials seems to be an under-investigated area which deserves further attention.

To fill this gap, Freeman’s (2014) taxonomy seems to be a suitable framework since on the benefits of adopting this taxonomy for the analysis of reading comprehension question types, she states that it “raises awareness of the different types of questions and tasks that can accompany a reading text” and could function as a materials evaluation checklist (p.101). She also points to the advantages of this taxonomy in teacher training and professional development in materials writing and highlights its benefits in “providing food for thought regarding what constitutes a suitable reading text” (p.101).

Yet, it has been argued that this taxonomy is a “blunt-instrument” because it has “mixed criteria of first language literacy for classifying questions thatare in fact designed to develop second languagereading skills” (Thornbury, 2014, pp.100-101). However, Charles (2015) considered it a “useful taxonomy of reading comprehension question types” (p. 898). Thornbury (2014) himself admits that Content type enjoys construct validity and “is exemplary in terms of its rigor and argumentation” (p.101). Besides, the researchers did not find a better, up-to-date trialed taxonomy which covers a wide range of post-reading comprehension questions and lends itself best to the current reading comp-qs available in EFL textbooks.

Considering the issues above, this study aims to follow a descriptive content analysis procedure “the basic goal of which is to take a verbal, non-quantitative document and transform it into quantitative data” (Cohen et al., 2000, p.164) to answer the following research questions.

- What reading comp-qs have the highest frequency in each level?

- Is there a significant difference among the frequencies of reading comp-qs across levels?

- Which reading comp-qs have the highest and lowest frequency means within the whole series?

The present study

Given the advantages of adopting the aforementioned taxonomy, this study aims to address the research lacuna mentioned earlier and respond to Freeman’s (2014) call for further research. In doing so, the Four Corners serieshas been chosen for analysis on the account that they are popular textbooks in language institutes in Iran as well as other parts of the world. The main author of this book is Jack C. Richards, who is a professor of applied linguistics and well-known scholar in English language teaching and materials development. Given Richards’ familiarity with current research and theories in language teaching and acquisition, the impact of this writer’s understanding of language and language use on materials’ design and the activities in the series and his strong emphasis assures making a connection between research and materials development (Richards, 2006). It is assumed that the results of this study would give teachers and materials developers an insight into developing comprehension questions based on sound theories of language learning and acquisition.

This study could make useful contributions since it is based on Freeman’s (2014) taxonomy, which is a combination of all the current reading taxonomies and is more likely to lend itself to the reading comprehension questions available in mainstream textbooks. This taxonomy seems to be more suitable than other taxonomies for L2 reading context as it is specifically designed to analyze L2 reading comp-qs and has been trialed on the most popular EFL textbooks. Therefore, it is expected to have addressed the shortcomings of previous taxonomies.

Method

Corpus

Four Corners (Richards & Bohlke, 2012) consists of four books (1, 2, 3, 4) and according to the teacher’s book it takes students from A1 (true beginner) to B1 (mid-intermediate) based on CEFR framework. The writers of the book argue that Four Corners is based on a communicative methodology and is designed to teach students to use English effectively within real world tasks. Each level is comprised of 12 units. The units have four main sections (A, B, C, & D). In section A, learners are exposed to some vocabulary and grammar points. In section B, students are presented with language in real communication and opportunities are provided to practice the language in communication. In section C, the second set of vocabulary and grammar points is presented. The focus in section D is on reading, writing, speaking, and listening in this order.

Procedure

To analyze reading comp-qs across different levels of Four Corners the reading texts and the accompanying exercises in section D of each level in which reading texts existed were selected. Since the focus of the study was on post-reading comprehension questions, the criteria for considering a piece of text as reading and post-reading comprehension questions needed to be determined. In order to have fixed and objective criteria for the analysis, only the texts and their accompanying exercises in the reading sections of the units were considered as reading. Therefore, the short pieces of texts which were in other sections and focused mainly on teaching vocabulary and grammar in context namely ‘language in context’ were excluded from the study.

As mentioned, to determine the post-reading comp-qs, only the questions, which came after the texts and required a closer investigation of the texts, were chosen for the analysis. Pre-reading questions, which mainly aimed to activate students’ schemata and give an overall picture of what learners are going to read, focusing on main ideas rather than a thorough reading of the text, were excluded from the study. Moreover, in this study (Freeman, 2014) the ‘question’ is a wide umbrella term, “which encompasses not only genuine interrogatives but also instructions for any text-related tasks” (p. 74). Based on this model, the post-reading comprehension questions in each level were categorized and further counted in terms of the number of times they occurred in each post-reading exercise.

While doing the study, some points were considered. In some cases, two or more questions were embedded in one exercise. In this case, each question was categorized and counted separately. For instance, on page 60 of Four Corners 3, exercise D reads: Which tips do you think are very useful, not useful, why? This exercise includes three questions, all of which were categorized as Personal Response type. Furthermore, some of the exercises consisted of sub-sections. In this case, each section was considered as a separate question, categorized and counted separately.

For example, the exercise below (Four Corners 1, p.42)included twelve questions, six of which targeted favorite days and the rest required students to find the reason mentioned in the text.

C. Read the message board again. What’s each person’s favorite day? Why? Complete the chart.

.png)

It should also be mentioned that the exercises whose answers were already given, and functioned as models for students were included in the count and the categorizing. Besides, some of the exercises seemingly consisted of one question but since they referred to a number of answers, they were considered as more than one question. For example, in Four Corners 1 page 112, the exercise reads: What adjectives describe each travel experience? Tell your partner. Since there were four travel experiences in four pieces of text, which made up a whole text and the learner needed to provide four adjectives, the exercise was considered as four questions.

A second rater holding an M.A. degree in TEFL, whose field of interest was developing materials for EFL learners, and who gave valuable help to the researchers, categorized the comp-qs. However, it should be noted that the second rater categorized some of the questions as both Reorganization and Inferential. After discussions, it was decided that the questions whose instruction included utterances like “complete the chart, number the steps or pictures in order, put the events in order, number the events, and write a name under the photos”, should be considered as Reorganization type and the other questions were categorized as Inferential. To determine the inter-rater consistency, Kappa coefficient formula was used. Kappa coefficient was first calculated for determining the degree of inter-rater consistency for each category (Explicit, Implicitand so on.) in each level individually and in the next step, the average Kappa coefficients of all the levels were added together and divided by four, which was the number of levels. The final average Kappa was calculated at 0.91.

To determine the significance of difference in question type, data were entered into SPSS. Seven variables were created, six of which represented reading comp-qs and the other one represented levels. The existence of a question type or lack thereof in each exercise was indicated by numerical values 1 and 0, with 1 indicating the existence and 0 lack thereof. Then, a Kruskal-Wallis test of independent samples was carried out. Besides, to determine the least and most frequent question type across the whole series, the means were compared in SPSS.

Results

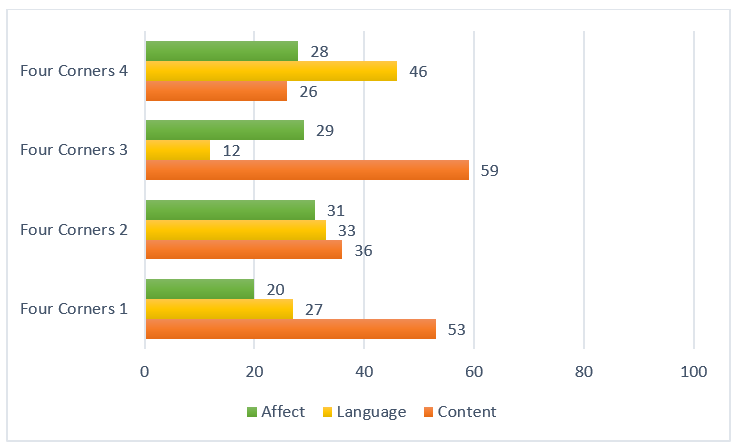

Figure 1 gives an overall view of the frequency of all the categories of reading comprehension questions in each level. It shows that Content question type was the most dominant in level one (53%), level two (36%) and level three (59%). However, in level four, Language category (46%) was the most prevalent of all.

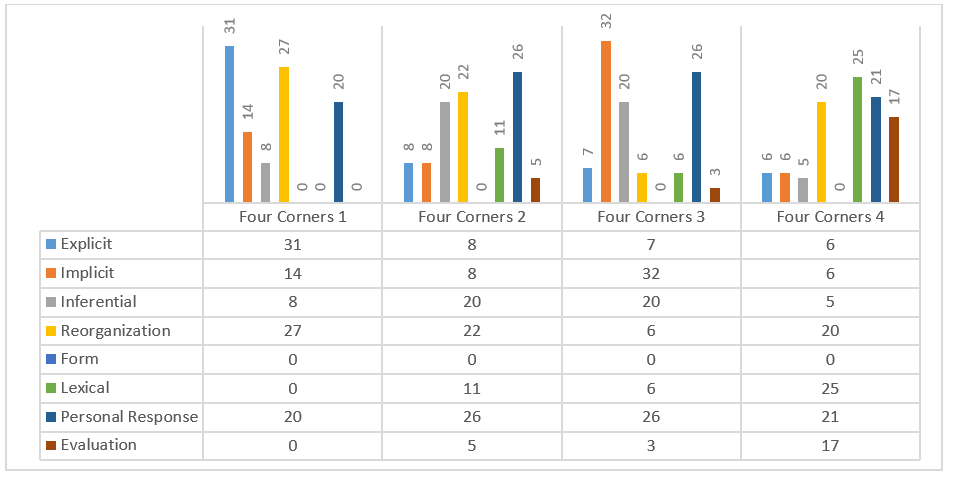

According to Figure 2, which gives a more detailed picture of the data, in levels one, two, three, and four the most frequent reading comp-qs were Explicit (31%), Personal (26%), Implicit (32%), and Lexical (25%) respectively.

Figure 1: Frequency of each reading comprehension question category across levels in percentages.

Figure 2: Frequency of each reading comprehension question type across levels in percentages

Table 1 shows the results of the Kruskal Wallis test of K independent samples indicating a significant difference (p < 0.05) in Explicit, Implicit, Reorganization, and Lexical category in comp-qs across levels.

.png)

Table 1: Significance level of reading comp-qs across levels

In addition, as Table 2 demonstrates, among all the reading comprehension questions in the whole series, Personal Response category was the most frequent while there was no Form question type.

.png)

Table 2:Frequency means of reading comp-qs in the whole series

Discussion

The first research question investigated the most dominant reading comp-qs in each level. As Figure 1 demonstrates, in levels one, two, and three, Content questions were the most dominant of all while in level four Language questions outnumbered other types. This could be an indication of the importance of Content questions, the high frequency of which is congruent with the results of Freeman’s (2014) study. However, in level four, Language question type outnumbered the other types, implying a shift of focus from understanding the text in previous levels to using reading to work on language in level four. However, it is to be noted that in level four, Language questions mainly focused on learners’ inferential skills to guess the meaning of vocabulary from context rather than language structures or form.

Figure 2 gives a more detailed picture of the data, revealing the dominance of Explicit questions in elementary level, which is quite justifiable on the grounds that beginner-level learners have low proficiency in English. This type of questions, whose answers are stated verbatim in the text, would demand little, if any, cognitive challenge on the part of learners (Freeman, 2014), thus giving them more confidence. Moreover, the high frequency of Personal Response questions in level two highlight the important role of engaging learners’ affect (e.g. interest, attitude, emotions) (Masuhara, 2013). Tomlinson and Masuhara’s (2013) call for designing tasks that relate language learning to learners’ personal lives gives further support to this finding.

The high prevalence of Implicit questions in level three is justified in the light of learners’ progress toward advanced level and the importance of increasing the cognitive level of questions in higher levels. Besides, the high frequency of Lexical questions in level four could be explained on the grounds that mid-intermediate learners have developed enough knowledge and skills to practice guessing the meaning of the words from context. It also gains support from the high popularity of guessing as useful (Nation, 2001; Schmitt, 2010) and frequently used strategy by learners for vocabulary learning (Fan, 2003). The importance of developing learners’ inferential skills to guess meaning from context (Nation, 2013) and the significance of vocabulary knowledge in reading comprehension (Anderson, 2015; Sidek & Rahim, 2015; Zhang & Anual, 2008) also lends support to the dominance of Lexical questions in level four. Since the probability and unpredictability of the occurrence of unknown words is high, guessing is an important strategy for coping with this problem (Na & Nation, 1985), which gains further significance especially in the absence of a more knowledgeable person (Schmitt, 2000). This strategy would also make learners independent in vocabulary learning.

Considering the high frequency of lexical question types in level four, it could be surmised that in second or foreign language learning, the goal of the reading section is not reading for its own sake, but it also involves some skill-based exercises.

Reviewing reading materials, Nutall (1985) refers to the publication of materials containing exercises which aim to promote reading skills and strategies and argues that incorporation of such exercises in reading materials is a “faith widely held” (p. 199). In addition, Masuhara (2013) quoting William and Moran states that “guessing the meaning of unknown words seems to be a typical example of language-related skill” (p. 373). This is also congruent with Nuttall’s (1996) recommendation as to using “language teaching texts for genuine tasks”, which would “help… the students to use context as a guide to interpreting some of the new language” (p.160).

The dominance of reading questions targeting lexical items compared with other question types is also reiterated in Freeman’s (2014) study which showed a tendency on the part of materials developers toward substituting Form with Lexical category over time.

The second research question aimed to examine if there is a significant difference in reading comprehension questions and task types across all levels of the Four Corners (1, 2, 3, 4). The results of a Kruskal Wallis test of K independent samples indicated that there is a significant difference in Explicit, Implicit, Reorganization and Lexical categories across levels.

The third research question investigated the most and least frequent question types in the whole series. According to table 2, Personal Response questions were the most dominant in the whole series, which is further substantiated in the light of the tendency of current textbooks to “relate topics and texts to their [learners’] own lives, views, and feelings” (Masuhara et al., 2008, p. 309). It could also indicate the writers’ propensity to engage learners in the act of genuine communication (Freeman, 2014), showing reactions to the text or relating it to their own lives.

It was also revealed that no comprehension question targeted Form. Since language-teaching materials reveal the writers’ theories of language learning and acquisition (Richards, 2006), this could be based on the writers’ beliefs that the reading section is not a good place for working on grammar. The view of the writers of Four Corners corroborates Masuhara (2013) who argues, “Materials should help learners experience the text before they draw their attention to its language” (p.381). It also seems to be in line with Masuhara’s (2013) recommendation as to making a distinction “between teaching reading and teaching language using texts” (Masuhara, 2013, p.170). The results of the study seem to be in contrast with those of Tomlinson and Masuhara (2013), which revealed the tendency of the writers of the mainstream course books to employ reading texts for language teaching.

Conclusion

This study aimed to analyze the reading comp-qs in all levels of Four Corners. The results indicated the dominance of Content questions in all levels except level four in which Language type was the most prevalent. It could possibly imply that one of the main aims of reading comprehension questions should be to make sure learners have understood the text. Then, when learners get more proficient in L2, readings could be used for working on skill-based language exercises such as guessing the meaning of unknown words from context, which is a common practice in mainstream textbooks.

Breaking down the results, we found that the highest percentage of reading comprehension questions in levels one, two, three and four were Explicit (Content), Personal (Affect), Implicit (Content) and Lexical (Language) types respectively. The statistical results also indicated a significant difference among all reading comprehension question types except in Inferential, Form, Personal and Evaluation types in all levels of the series.

The lack of Form questions could imply that Form question type should not be incorporated in reading sections, which is in line with Tomlinson and Masuhara’s (2013) bemoaning the increased attention given to explicit knowledge of grammar at the cost of the “affective and cognitive engagement” (p. 233). The results of this study could benefit materials developers by giving them an insight into the type of reading comp-qs available in a popular English textbook. It could also help teachers make sound and informed decisions when developing their own materials.

However, this study suffered from some shortcomings that could be dealt with in future research. In this study, the researchers only analyzed reading comprehension questions and task types within the Four Corners. However, to increase the generalizability of the results, future studies could investigate reading comprehension question types across more series. In addition, when categorizing the post-reading tasks, the questions whose answers were already given and functioned as a model were included in the study. Since such model responses did not exist in all the tasks, this could have affected the validity of the results. Therefore, this issue should be considered in future studies.

As a suggestion for further research, it might be interesting to analyze the books published by two different publishers such as Longman and Oxford to find out if they tend to have special preferences. Moreover, English and American versions of EFL textbooks could be investigated to determine if there is a significant difference between them.

This study only focused on the student book. However, it would be worthy of research to compare post-reading comprehension questions and tasks of student books with those available in their accompanying workbooks.

In this study, only texts in reading sections of the textbooks were examined and the texts in other sections namely ‘Language in Context’ whose focus was drawing learners’ attention mainly to the language features were excluded. However, future research could include those texts and make a comparison between these two sections. In addition, different books of the same author could be investigated to see if they follow a specific pattern in terms of post-reading comprehension questions and task types.

References

Adli, N. & Mahmoudi, A. (2017). Reading comprehension questions in EFL textbooks and learners’ levels. Theory and Practice in Language Studies. 7(7), 590-595. http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/tpls.0707.14

Aebersold, J. A & Field, M. L. (1997). From reader to reading teacher: Issues and strategies for second language classroom. Cambridge University Press.

Anderson, N. (2015). Developing engaged second language readers. In M. Celce-Murcia, D. M. Brinton, & M. A. Snow (Eds.), Teaching English as a second or foreign language (4th ed.) (pp. 170-188). National Geographic Learning.

Birjandi, P. & Alizadeh, I. (2013). Manifestation of critical thinking skills in the English textbooks employed by language institutes in Iran. International Journal of Research Studies in Language Learning,2(1), 27-38. https://doi.org/10.5861/ijrsll.2012.100

Bloom, B. S. (Ed.) (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives, Handbook 1: Cognitive domain. Longman.

Charles, M. (2015). [Review of the book] English language teaching textbooks: Content, consumption, N. Harwood (Ed.). TESOL Quarterly, 49(4), 897-899. https://www.jstor.org/stable/43893796

Cohen, L., Manion, L., & Morrison, K. (2000). Research methods in education (5th ed.). Routledge.

Fan, M. Y. (2003). Frequency of use, perceived usefulness, and actual usefulness of second language vocabulary strategies: A study of Hong Kong learners. The Modern Language Journal, 87(2), 222-241. https://doi.org/10.1111/1540-4781.00187

Freeman, D. (2014). Reading comprehension questions: The distribution of different types in global EFL textbooks. In N. Harwood (Ed.). English language textbooks: Content, consumption, production. (pp. 73-110) Palgrave Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137276285_3

Garton, S. & Graves, K. (2014).Materials in ELT: Current issues in international perspective on materials in ELT. Macmillan. https://doi.org/10.1057/9781137023315_1

Grabe, W. (2009). Reading in a second language: Moving from theory to practice. Cambridge University Press.

Igbaria, A. K. (2013). A content analysis of the wh-questions in the EFL textbook of Horizons. International Education Studies, 6(7), 200-224. https://doi.org/10.5539/ies.v6n7p200

Litz, D. R. A., (2005). Textbook evaluation and ELT management: A South Korean case study. Asian EFL Journal, 48, 1-53.

Masuhara, H., Hann, N. Yi, Y., & Tomlinson, B. (2008). Survey review: EFL courses for adults. ELT Journal, 62(3), 294-312. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/55.1.80

Masuhara, H. (2013). Materials for developing reading skills. In B. Tomlinson (Ed.), Developing materials for language teaching (pp. 265-289). Bloomsbury.

McDonough, J., Shaw, C., & Masuhara, H. (2013). Materials and Methods in ELT: A Teacher’s Guide. (3rd ed.). Wiley-Blackwell.

Mckee, S. (2012). Reading comprehension, what we know: A review of research 1995 to 2011. Language Testing in Asia, 2(1), 45-58. https://doi.org/10.1186/2229-0443-2-1-45

Na, L. & Nation, I. S. P. (1985). Factors affecting guessing vocabulary in context. RELC Journal, 16(1). 33-42. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F003368828501600103

Nation, I. S. P., (2001). Learning vocabulary in another language. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9781139524759

Nutall, C. (1985). Survey review: Recent materials for the teaching of reading. ELT Journal. 39(3). https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/39.3.198

Nuttall, C. (1996). Teaching reading skills in a foreign language. Heinemann.

Razmjoo, S. A. & Kazempourfard, E. (2012). On the representation of Bloom's revised taxonomy in Interchange course books. The Journal of Teaching Language Skills, 31(1), 171-204. https://doi.org/10.22099/JTLS.2012.336

Richards, J. C. (1993). Beyond the text book: The role of commercial materials in language teaching. RELC Journal, 24(1), 1-14. https://doi.org/10.1177/003368829302400101

Richards, J. C. (2001). Curriculum development in language teaching. Cambridge University Press. https://doi.org/10.1017/CBO9780511667220

Richards, J. C. (2006). Materials development and research–Making the connection. RELC Journal, 37(1), 5–26. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688206063470

Richards, J. C. (2014). The ELT Textbook. In S. Garton, & K. Graves (Eds.), International Perspective on Materials in ELT (pp. 19-36). Palgrave Macmillan.

Richards, J .C. & Bohlke, D. (2012). Four Corners. Cambridge University Press.

Roohani, A., Taheri, F., & Poorzanganeh, M. (2014). Evaluating Four Corners textbooks in terms of cognitive processes using Bloom’s revised taxonomy. Journal of Research in Applied Linguistics, 4(2), 51-67. http://rals.scu.ac.ir/article_10538.html

Schmitt, N. (2000). Vocabulary in language teaching. Cambridge University Press.

Schmitt, N. (2010). Researching vocabulary: Vocabulary research manual. Palgrave Macmillan.

Sheldon, L. (1988). Evaluating ELT Textbooks and Materials. ELT Journal, 42(4), 237-246. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/42.4.237

Sidek, H .M. & Rahim, H. Ab. (2015). The role of vocabulary knowledge in reading comprehension: A cross-linguistic study. Procedia–Social and Behavioral Sciences, 197, 50-56. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.sbspro.2015.07.046

Thornbury, S. (2015). [Review of the book] English language teaching textbooks: Content, consumption, production, N. Harwood (Ed)]. ELT Journal, 69(1), 100–102. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccu066

Tomlinson, B. (2012). Materials development for language learning and teaching. Language Teaching. 45(2). 143-179. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444811000528

Tomlinson, B. & Masuhara, H. (2013). Adult course books. ELT Journal. 67(2), 233-249. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/cct007

Ur, P. (1996). A Course in language teaching: Practice and theory. Cambridge University Press.

Willis, J. (2008). Teaching the brain to read: Strategies to improve fluency, vocabulary, and comprehension. Association for Supervision and Curriculum Development.

Zhang, L. J. & Anual, S. B. (2008). The role of vocabulary in reading comprehension: The case of secondary school students learning English in Singapore. RELC, 39(1), 51-76. https://doi.org/10.1177/0033688208091140