Language teacher education has existed as an established subfield of applied linguistics research since at least the 1990s, with pioneering studies conducted in the 1970s (Li, 2017). Deriving from a general interest in all teachers' mental lives that started to take shape as a research area in the 1980s (e.g., Clark & Peterson, 1986), language teacher education is now a burgeoning field. It uses a variety of constructs such as teachers' beliefs (e.g., Horwitz, 1985), knowledge (Golombek, 1998), cognitions (Borg, 2003), attitudes (Weekly, 2018), self-perceptions (Borg, 2001), and language ideologies (Razfar, 2012; Young, 2014). The literature about language teacher education is thus vast, and the theoretical orientations and methods used to study the various aspects of it is increasingly diverse and complex (Burns et al., 2015). A construct coming from educational psychology that has recently begun to be applied to teacher education is that of threshold concepts, or TCs. TCs are disciplinary concepts (e.g., 'interlanguage') that enable novices in a discipline to transform their understanding of a phenomenon; to be a TC, a concept needs to display a certain number of features (see discussion below). TCs offer an alternative lens to focus on teacher education, one that co-exists with other lenses such as attitudes, beliefs, and ideologies. The goal of this paper is to review only the literature that has explicitly used TCs as a theoretical lens to look at aspects of teacher education, some of which have already been extensively addressed from other perspectives. For example, teacher classroom talk has been investigated from a TC perspective by Skinner (2017) alone. Therefore, in light of our goal, we only review Skinner (2017) despite the fact that many other studies have analyzed teacher talk using other constructs. This choice in no way means that we are not cognizant of or do not value other theoretical perspectives such as teachers' beliefs, attitudes, or language ideologies. Rather, it is a consequence of our goal to focus on a new construct (and its set of methods), TCs, that has recently been added to the existing repertoire of theoretical lenses to look at teacher education. A caveat here is that some scholars working in the TCs tradition have at times deployed other constructs, such as beliefs or attitudes, without providing a definition of these admittedly contested and complex terms. A limitation of our review is that we do not undertake an interrogation of the ways that TC scholars have mobilized those constructs. This limitation is due to the fact that the construct in focus in this review is TCs exclusively. Of course, readers may wonder why a new construct such as TCs is relevant in light of the fact that so many other ways of looking at teachers' mental lives in the context of teacher education are already available. One justification is that one way that knowledge moves forward in the social sciences and the humanities is by adding new theoretical perspectives to existing ones (Bernstein, 1999). Another is that, as we hope this paper will show, TC research findings may offer ways to streamline curriculum design and expedite language teachers' learning of difficult disciplinary concepts.

Despite the vastness and complexity of constructs used in the field, several themes are clear in the published literature. One of them is that, according to Song (2015), belief has been the preferred construct to research language teachers' cognitions. However, as many scholars have pointed out (Pajarés, 1992; Barcelos, 2003; Kubanyiova, 2012), the term 'belief' has been used with many different definitions by different authors and in different strands of inquiry. When we deploy this term ourselves, we mean propositions that are held to be true; these propositions are both individual (i.e., held in the minds of individuals) and social, and may or may not align with empirical evidence and/or accepted scientific knowledge (Barcelos, 2003, 2007; Kubanyiova, 2012). As stated above, some of the authors we quote and some of the studies we review have used the term differently or without providing a definition. We do not further probe what they mean since our focus is not on beliefs, but on TCs.

Within the prevailing focus on beliefs, a strong substrand of research has been centered on teachers' pre-scientific, non-reflective, potentially detrimental beliefs about the nature of language learning and teaching. As stated by Kubanyiova (2012),

There is a general consensus that if these beliefs are not made explicit, questioned and challenged, teachers' pre-training cognitions regarding teaching an L2 may be influential throughout their career despite the training efforts. (p. 13)

Accordingly, another theme is the widely held assumption that various subfields of linguistics and applied linguistics are relevant to language teacher education in order to inform practice and even change teachers' non-reflective, detrimental beliefs (Abreu, 2015; Bartels, 2005; Busch, 2010; Dankić, 2011). Yet another theme is that, according to Horii (2015), this assumption co-exists with lingering concerns about the practical value of the knowledge derived from training in those subfields. These concerns stem partly from the mixed, uneven results of studies exploring the impact of training and linguistic Second Language Acquisition (SLA) discourse analysis theory on teachers' thinking and practice in various areas (e.g., Borg, 2005, 2006, 2012; Debreli, 2016; Gómez et al., 2019; Kamiya & Loewen, 2014; Lo, 2005; Markham et al., 2016; Swierzbin & Reiman, 2019).

According to Kubanyiova and Feryok (2015), despite the field's great diversity, it has failed to address adequately crucial issues such as how teacher education can best facilitate teacher learning. These concerns echo Kubanyiova's (2012) earlier assertion that much of the knowledge generated by language teacher education research is not grounded on a firm-enough theoretical basis. Kubanyiova (2012) suggests that an expansion of the constructs and methods used to theorize and research language teacher education (i.e., beyond the construct of beliefs) can function as a remedy to these issues. In particular, she suggests that an explicit focus on conceptual change as both a construct and process can shed light on the processes whereby some trainees succeed and others fail to develop more functional cognitions, with the latter being a critical research focus in the field.

Conceptual change is a construct with a large and strong research tradition in educational psychology. It refers to 'a restructuring of existing knowledge representations a more radical change in the teacher's conceptual system' (Kubanyova, 2012, p. 36) not achieved by a mere addition of new information. Some studies in language teacher education have used the construct of concept change without a theoretical grounding on the construct and its methods as specified in educational psychology (e.g., Selvi & Martin-Beltrán, 2016). Other studies have used belief change (Abreu, 2015) rather than conceptual change as defined above, and they have also not used the conceptual and methodological apparatus of conceptual change. So far, it appears that only Kubanyiova (2012) has used the educational psychology construct of conceptual change in teacher education with the same conceptual basis and method as studies in educational psychology. By contrast, threshold concepts is a recent and growing educational psychology construct related to conceptual change that has been applied to language teacher education by a growing number of papers. Svalberg (2015) has endorsed the role that TC research can play in constructivist, socially-situated language teacher education research. In particular, a TC approach seems promising in light of the value of cognitive conflict between new and prior cognitions as a pedagogical tool in language teacher education (Svalberg, 2015). An extremely important goal of TC research is to examine the variety of concepts that exist in any given field or discipline and isolate those that possess certain features (presented in the next section) that make them threshold concepts. Against this backdrop, this paper addresses the following research questions:

- Which TCs in language teacher education have been identified so far in the literature that has explicitly used a TC approach?

- In what contexts has threshold concept research in language teacher education been conducted?

- What designs and methods have been used in such research?

As stated above, this review is limited to only those studies which have explicitly used a TCs approach to investigate such concepts. Another limitation is that neither our review nor the TC approach is immediately concerned with the connection between TCs and language students' learning of target languages. Rather, a TC approach is concerned with establishing which concepts are TCs in teacher education in order to facilitate teacher learning. This is a trend in TC research as its goal is precisely to identify, out of the vast array of concepts in any discipline, which ones are TCs so that they can be mobilized for curricular planning purposes. This is valuable because TCs are more likely than other concepts to be difficult to learn and to lead to cognitive conflict and conceptual change. Against this backdrop, the next section turns our attention to the history and nature of the construct of threshold concepts.

Threshold concepts

The construct of threshold concepts was first proposed by British educational psychologists Jean H. F. Meyer and Ray Land in Meyer and Land (2003), and subsequently developed in a series of publications (Meyer & Land, 2005, 2006). The following points about TCs need to be understood before moving forward:

- Following Land et al. (2010), only disciplinary concepts (i.e., those with an established tradition of being used within a discipline in the hard sciences, the social sciences or the humanities for the purposes of legitimate systematic inquiry) can be TCs.

- Their grounding on a discipline or field's systematic inquiry makes TCs different from beliefs, as beliefs may or may not reflect accepted scientific knowledge (Barcelos, 2003, 2007); Kubanyiova, 2012).

- While all TCs are disciplinary concepts, not all disciplinary concepts are TCs (Meyer & Land, 2003, 2005, 2006).

- Likewise, the beliefs of some language teachers may be grounded on TCs (Devitt & McKendry, 2014; Moroney et al., 2016), but, as shown by Perales-Escudero (2017), TCs are not beliefs, and not all beliefs are related to TCs.

At the core of TCs as a construct is the notion that certain concepts within specific disciplines bring about in learners 'a transformed internal view of subject matter, subject landscape, or even world view' (Meyer & Land, 2006, p. 3). Such concepts are TCs. TCs do not merely add knowledge like other disciplinary concepts do, but transform novices' understandings of those aspects of the world that are the subject matter of their discipline (Meyer & Land, 2005). This process is akin to accommodation in conceptual change as defined above. It can be related to belief change, but only to a specific kind of belief change that might occur upon a language teacher having learned deeply a new, discipline-grounded concept. Thus, a TC is

akin to a portal [hence the label 'threshold'], opening up a new and previously inaccessible way of thinking about something. It represents a transformed way of understanding, or interpreting, or viewing something without which the learner cannot progress. (Meyer & Land, 2003, p. 1)

As stated by Barradell (2013), 'the term 'threshold concept' first emerged as part of the Enhancing Teaching Learning (ETL) Environments in Undergraduate Courses project' (p. 265) in the United Kingdom. This project did not focus on language learning or language teacher education, but on university-level teaching of several other disciplines such as economics or engineering. TCs were offered as a potential solution to the problem of deciding which content to focus on in disciplinary teaching and learning, since 'ahigh volume of content has the potential to encourage students to adopt a superficial approach to learning (Ramsden, as quoted in Barradell, 2013, p. 268). The preceding sentence contains the term 'students' because TC research originally focuses on college students. For the purposes of this paper, we consider pre-service language teachers (some of whom are college students majoring in language teaching) and in-service teachers taking training courses as students of teaching. Any subsequent mention of 'students' is to be understood as teacher trainees, whether pre-service or in-service. Unless explicitly indicated, none of the papers we review and none of our own claims refer to language learners.

TCs are seen as a solution to the problems of content overload and superficial learning because they are strongly centered on the students' experiences of learning and offer 'a way to streamline what is taught in a way that is valuable to both teachers and learners' as 'they can help to define critical points in students' learning' (Barradell, 2013, p. 268). Thus, a primary feature of TCs is their intended use in assisting curricular design by helping to select, organize, present, and assess content (Entwhistle, 2003). In this way, a TCs approach might help to address the gaps in our understanding of how language teacher education can best facilitate teacher learning, which was identified by Kubanyiova and Feriok (2015).

Meyer and Land (2005, 2006) have listed several features that disciplinary concepts must have in order to be considered TCs. These features are not different thresholds to be crossed in the acquisition of a concept. Rather, they are features that some disciplinary concepts possess and others do not. Those concepts which possess these features are called threshold concepts. Our exposition below is based on the synthesis in Perales-Escudero (2017) and also offers our own commentary based on other sources. As features of TCs, the following do not have an intrinsic connection to language teacher education. Rather, some concepts in language teacher education courses with a disciplinary focus (e.g., 'interlanguage' in an SLA course, 'rank scale' in a Systemic-Functional Linguistics course) may possess some or all of those features. A goal of TC research in language teacher education is to identify which concepts in language teacher education are TCs. This is because TCs are held to have a greater impact than other, non-TC concepts, on teachers' conceptual change, and are also held to be more difficult to acquire. Thus, identifying TCs in the discipline-informed contents that make up much of language teacher education (e.g., linguistics, SLA, discourse analysis, educational psychology, grammatical analysis) is valuable in order to increase the impact of teacher education on teacher development. Specific connections between the features and aspects of language teacher education are made in our summary and discussion of the papers included in the literature review.

The first and most important feature of threshold concepts is their transformative nature. This means that once a TC has been truly learned in all its depth and complexity, it leads to a new, previously unavailable understanding of the target phenomena (Ricketts, 2010; Shanahanel al, 2010). This process has been called accommodation in conceptual change research (Posner et al., 1982), and 'represents a more radical change in the teacher's conceptual system' than the mere addition of new concepts (Kubanyiova, 2012, p. 36).

The second feature of threshold concepts is that they are troublesome in various senses. They are difficult to learn and act as barriers to further development. In another sense, their internalization destabilizes students cognitively and even emotionally because they can be very alien and alienating (Meyer & Land, 2006). As a result, students tend to go through what has been called a 'liminal space' or 'state of liminality' (Meyer & Land, 2006, p. 19). This 'liminal space' (from Latin limen = door or window frame, threshold, boundary) refers to a period of time, more-or-less prolonged, during which the students may at first acquire the concept only superficially, then appear to have acquired and use the concept more deeply, to then go back to a superficial understanding and/or application, and so on. According to Meyer and Land (2006), liminal behaviors 'may involve both attempts at understanding and troubled misunderstanding' (p. 24) as well as 'mimicry' (p. 24) or mere performance/reproduction without true understanding. Meyer and Land (2003) add that other sources of troublesomeness are the often tacit nature of threshold concepts and the fact that they are situated within the specialized, technical language and discourse of the disciplines. This is related to language teaching because teacher trainees are sometimes required to learn difficult disciplinary concepts with strong implications for their practice, such as 'interlanguage'; they may, however, resist such implications or understand the concepts only superficially (Perales-Escudero, 2017).

The third feature of threshold concepts is their irreversibility. 'The epistemic transformation produced in the students is irreversible; that is, they cannot go back to their prior understanding of the phenomenon. For this reason, their cognitive representation of the phenomenon is forever altered' (Perales-Escudero, 2017, p. 125). It is perhaps for this reason that 'the troublesome nature of threshold concepts is not immediately recalled by those who have already acquired them' (Barradell, 2013, p. 269). In other words, they tend to become part of the tacit knowledge of experts in a discipline or field (Meyer & Land, 2003). Irreversibility is related to language teacher education in two ways. First, it highlights processes whereby teachers' thinking about an aspect of language, language learning, or language teaching, might be forever changed (Perales-Escudero, 2017; Orsini-Jones, 2007, 2008; Orsini-Jones & Jones, 2010), even if such changes in thinking do not always lead to changes in practice (Devitt & McKendry, 2014; Moroney et al., 2016). Second, it can help teacher educators reflect on the possibility that their holding some TCs as tacit knowledge might make such TCs a part of the hidden curriculum in language teacher education.

The fourth feature of threshold concepts is their integrative nature, or integrativeness. 'They work to integrate disciplinary content, revealing connections between several concepts and themes that may not be apparent in their absence' (Perales-Escudero, 2017, p. 125). This feature makes them akin to what Maton and Doran (2017, pp. 60-61) have called 'conglomerates,' or technical words that condense many other technical meanings. An example of the connection between integrativeness and language teacher education is in the work of Orsini-Jones and colleagues (2007, 2008; Orsini-Jones & Jones, 2010). They show that learning the TC of rank scale deeply requires understanding other related grammatical concepts. Sandoval Cruz et al. (2019) also show that making connections between the concept of interlanguage and related concepts such as input, output, and non-target-like forms can lead to changes in how pre-service teachers approach correction of non-target-like forms in assessment situations.

The fifth feature of threshold concepts is boundedness. This is an admittedly difficult to understand characteristic (Wilson et al., in Barradell, 2013) and also an optional one (Meyer & Land, 2003). In defining it, Meyer and Land (2003) merely stated that 'any conceptual space will have terminal frontiers, bordering with thresholds into new conceptual areas' (p. 5). Their subsequent discussion suggests at least two ways to interpret boundedness. One is 'the demarcation between disciplinary areas' (Meyer & Land, 2003, p. 5). Then, boundedness seems to refer both to the situatedness of threshold concepts within the confines of a discipline and their role in establishing those confines. However, it has been suggested that threshold concepts can also work as transdisciplinary links (Schwartzman, 2010). The other interpretation suggested by Meyer and Land (2003) is 'areas of the curriculum' (p. 5), which may mean anything from whole courses within a program of study to specific topics or units within a syllabus. Brunetti, Hofer and Townsend (2014) suggest that, especially for interdisciplinary fields, boundedness may be usefully reinterpreted in terms of being situated in a field of practice and helping to define it. This is related to language teaching and language teacher education because they are fields of practice influenced by several disciplines (Pennington, 2015). Thus, identifying which disciplinary concepts are TCs in these fields might be useful in defining the fields themselves and characterizing their impact on teachers' thinking.

The sixth feature of threshold concepts is their discursive nature. As stated by Meyer and Land (2006), the acquisition of a threshold concept results in the students' ability to deploy language in new, disciplinary ways. These new ways of using language also index new, disciplinary ways of thinking: 'The acquisition of transformative concepts, it is argued, brings with it new and empowering forms of expression that in many instances characterise distinctive ways of disciplinary thinking' (Meyer & Land, 2006, p. 20). The authors stress that shifts in both syntax and semantics may be involved in this process, which seems to fit well with the extensive body of research on disciplinary registers in applied linguistics. An obvious implication for language teacher education is that it is worth exploring how language teachers come to appropriate (or not) a field-specific or discipline-specific register (e.g., that of SLA or discourse analysis).

The seventh and final characteristic of threshold concepts is that they are reconstitutive, that is, they involve identity changes. In Meyer and Land's (2006) words:

the discursive nature of threshold concepts entails a reconstitution of the learner's subjectivity [ ] The emphasis here is on the indissoluble interrelatedness of the learner's identity with thinking and language [ ] Threshold concepts lead not only to transfigured thought but to a transfiguration of identity and adoption of an extended or elaborated discourse. (p. 21)

The reconstitutive feature has obvious implications for language teacher education: identifying TCs in this field would help to see which concepts have the strongest effects on teachers' disciplinary identity shifts.

As explained by Barradell (2013), there is no consensus within the community of TC scholars as to which of these features are absolutely essential and which are optional for a concept to be considered a threshold concept. However, the first two are often prioritized in determining whether a disciplinary concept is also a threshold concept. Most often, the perspectives of faculty are used in order to identify threshold concepts using methods such as interviews, questionnaires, and surveys. Students' perspectives have been addressed to a lesser extent by using responses to exam questions and problems, and classroom observations (Barradell, 2013). The author highlights the importance of enhancing methodological rigor in the identification of threshold concepts and advocates for research designs that integrate the perspectives of experts in the target discipline, such as professors and lecturers), as well as students and educational researchers.

The focus of a threshold concepts approach on emotions, cognitive conflict, identity and the perspectives of multiple stakeholders locate it within the 'warming trend' in conceptual change research to go beyond individual cognition and include emotional and social dimensions (Kubanyiova, 2012). Having explained the nature of threshold concepts and some of the methods used to identify threshold concepts, we now turn attention to the methods for our literature review.

Methods

In order to find papers focusing on TCs in language teacher education, we searched Scopus, Google Scholar, and Research Gate. The search terms we used were threshold concepts, language teachers, teacher education, second language, and foreign language. We also used the reference list from articles found in the initial search in order to look for other papers. Once we could not find any more hits in either of the databases, we proceeded to select which papers to include/exclude. The requirements for inclusion were: a) the paper should contain empirical data, b) papers published in proceedings were included only if they had not been published as articles or book chapters at a later date. As a result of this process, we discarded two of the nine papers we had found. Thus, the sample for this literature review consists of seven papers. We read and summarized each paper and compared them in terms of proposed TC, context, sample, methods, and main findings. The summaries and the results of this comparison are shown in the next section.

Results

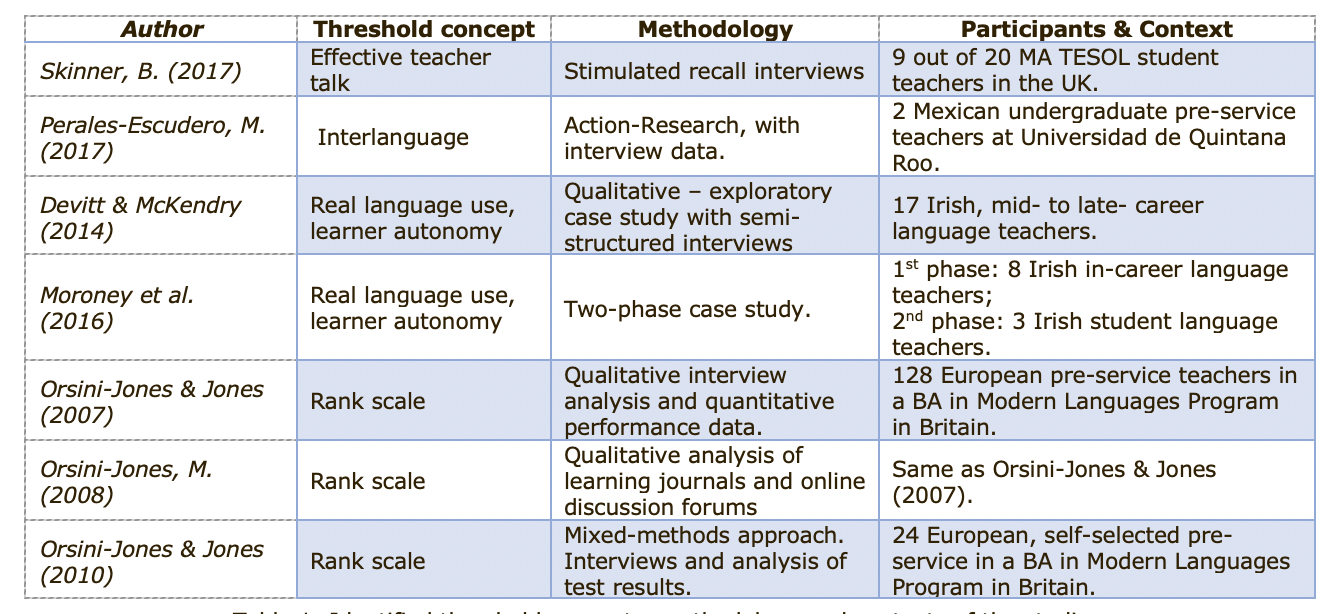

In Table 1, we summarize the studies included in this literature review. Where applicable, the papers are grouped according to authorship; papers by the same author(s) are presented chronologically. Then, they are discussed in the paragraphs below.

Table 1: Identified threshold concepts, methodology and contexts of the studies.

Perales-Escudero (2017) introduced threshold concepts in Spanish, proposed interlanguage as a threshold concept and reported preliminary results of an action-research project investigating the internalization of this concept by a group of Mexican, pre-service teachers majoring in ELT. After introducing TCs, the author proposed a new construct, that of pathway concepts, to represent the common-sense understanding that students have of a phenomenon captured in their discipline by a TC. He then developed an argument about interlanguage as a TC, with common-sense ideas of error as the corresponding pathway concept. The fulcrum of his argument was that understanding errors and mistakes as systematic products of interlanguage rules could change teachers' views of errors from a deficit perspective (i.e., one that sees errors as products of insufficient intelligence and as worthy of punishment) to an inquiry-based one. The latter view could enable teachers to approach errors with the goal of understanding the interlanguage rules that produce them, rather than ignoring them or chastising the students who produce them. Such an approach, in turn, can be pedagogically fruitful as it could enable teachers to help learners discover and change their own interlanguage rules. This kind of change is an example of the first feature of TCs presented in the previous section, namely their transformative nature. Next, in the tradition of Systemic-Functional Linguistics, Perales-Escudero (2017) presented and illustrated a classroom genre of his own design, the refutation sequence, which he used in his action-research study to ease the transition from the pathway concept to the TC of interlanguage. The participants in his study were TEFL majors enrolled in a psycholinguistics course at Universidad de Quintana Roo (pre-service teachers). He reported interview data of two students with opposite experiences. One of them expressed emotional resistance to accepting the concept of error as a product of the interlanguage system rather than a moral or cognitive deficit; he was thus in the liminal stage of troubled misunderstanding. The other found this understanding liberating as it allowed her to see her own language productions in English under a different, more positive light. The author speculated that these views may be due to the participants' different degrees of command of English and different perspectives on prescriptivism and descriptivism (i.e., whether they adhere to a prescriptivist or a descriptivist view of language).

Skinner (2017) introduced the concept of Effective Teacher Talk (ETT) as a TC, with the explicit goal of contributing to the development of the TESOL teacher education curricula. She considered ETT to be a TC due to its crucial role in the success of L2 pedagogy. The author connected ETT with Walsh's (2006) framework for lesson components or 'phases' (materials, managerial skills and systems, and classroom context). In this framework, each phase demands specific interactional features. Thus, teacher talk must go in line with those interactional needs (Walsh, 2006). At the same time, she uses the three levels of liminality for TCs (mimicry, attempts at understanding, troubled misunderstanding) (Meyer & Land, 2005) to determine to what extent her pre-service teachers understood effective teacher talk as a tool to promote language learning in classrooms.

Although a methodological design was not explicitly reported in this article, Skinner (2017) used stimulated recall interviews, commonly used in naturalistic studies (Lyle, 2000). Her participants were nine MA TESOL student teachers. Five were non-native speakers of English (NNSs) and four were native speakers (NSs). All of them were taking a unique kind of course in a British MA program: a six-week teaching practice placement in the European mainland. She interviewed these students using two recorded 30-minute teaching practice sessions as stimuli for the interviews. Student teachers were asked to select two 10-minute modes/phases in each lesson and the interview took place around those sections (Walsh, 2006).

Skinner (2017) found that four participants 'three NNSs and one NS 'remained in the pre-liminal stage. They did not link their teacher talk with pedagogical purposes and were mainly concerned with their personal performance as language users. They focused on linguistic aspects, such as accuracy, the volume of their voice, and clarity. For the three NNSs, their understanding of effective teacher talk related to their own use of English as NNSs in charge of a group of other NNSs of English who may or may not judge their L2 proficiency. Conversely, the three participants in the liminal stage and the two participants in the post-liminal stage did see a link of their teacher talk with pedagogical purposes. The participants in the liminal stage 'one of them an NNS 'realized the importance of teacher classroom discourse for the dynamics of their teaching but this was troublesome because this meant challenging their teaching techniques. In particular, the NNS in this stage experienced conflict due to the differences between ETT and what he had believed to be effective techniques in his teaching context, Bangladesh. Finally, those student teachers in the post-liminal stage, two NSs of English, realized how ETT was appropriate for pedagogical purposes and understood how specific kinds of questions can promote interaction among students. According to Skinner (2017), these two teachers felt good about the results they obtained and changed the way they perceived the use of speech in the classroom. What Skinner's (2017) results mean for language teacher education is that liminality can be prolonged when teachers' beliefs about what constitutes good practice are deeply rooted in their prior teaching experiences and are challenged by new knowledge.

In addition, Devitt and McKendry (2014) sought to identify TCs in a sample of 17 mid- to late-career practicing language teachers in both Northern Ireland (nine) and the Republic of Ireland (eight). The languages they taught included Irish, German, French, Spanish, and Italian. Although the authors do not report adhering to a specific design, they do provide their inclusion-exclusion criteria and label their data source and analytic approach. To be included, teachers had to have at least five years of experience in a variety of school types. The selected participants were interviewed, and the resulting transcripts were analyzed using semi-open thematic analysis. As a result of the analysis, the authors identified two TCs in the participants' interviews: real language use and learner autonomy. Subthemes in the former included a focus on meaning, using the target language, using authentic materials, structuring opportunities for meaningful language use, and establishing connections with other courses. Subthemes in the later included 'building learner confidence and motivation, fostering error tolerance, scaffolding learners' strategy use, target setting' (p. 3). Of note is the finding that 'most of the participants identify 'seeing what works' as the major catalyst for change over their career' (p. 3).

Another theme that emerged was the role of contextual factors as supports or barriers for conceptual change and for enacting TCs in the classroom. Among the supports were dialogue with peers, curriculum or assessment changes, involvement with research, and continuing professional development. The barriers encompassed the prevalent modes of assessment, absence of peer support or dialogue, school culture (exemplified by parental pressure and student expectations), and 'logistics and time' (p. 4). An important conclusion drawn by Devitt and McKendry (2014) in connection with the TC features of liminality and irreversibility is that

The tensions between knowledge, beliefs and practice identified here and in the literature suggest that knowledge must be sustained and validated by practice. In the absence of this, the teachers experience frustration and possibly even a sense of impostorship where there is a gulf between idealised and actual practice (Brookfield 2006). Taking the threshold metaphor, they re-experience the liminal, pre-threshold space with its characteristics of frustration, limitation and mimicry, using the discourse but not following through in action. In this sense, concepts may be irreversible but their associated practices are not. (p. 5)

An implication of these findings is that teachers cannot be assumed to automatically and easily transfer the TCs learned in their formal education or training even if they have internalized them deeply. Rather, contextual factors mediate the possibility of such transfer. Teacher educators and policy makers should be mindful of this and equip teachers and contexts with the necessary tools for teachers' knowledge base to transform their actual practice in meaningful ways.

Moroney et al. (2016) reported a 2-phase, TC case study in Ireland focusing on the transition from novice to veteran language teacher. The authors framed their study with the concept of adaptivity (Hammerness, et al., 2007), which refers to internal or external prompts for change, as a vital feature for language teachers throughout their teaching career. They also considered Borg's (2006) concept of teacher cognition. In the first phase, the authors interviewed 8 in-service Irish language teachers on core topics which they connected with 'good teaching practices'. During their interviews, these teachers, directly or implicitly, identified real language use and fostering learner autonomy as threshold concepts in their professional practice, concepts that were transformative even for themselves. This is consistent with the findings in McKendry and Devitt (2014). Moroney, et al. (2016) also reported that almost all in-service teachers expressed that curricular principles may constrain their ability to enact their TC-grounded beliefs on good teaching practices. Example of these constraining curricular principles were the connection between the exam system and the use of target language.

In the second phase, the authors worked with 3 pre-service French language teachers in order to keep track of their experience acquiring the TCs previously reported by the in-service teachers. The data collection took place while the participants were taking a one-year Initial Teacher Education (ITE) program. The student teachers had to send reflective journals via e-mail every 2 or 3 weeks, reporting challenges and improvements in their pre-service practice. A one-on-one semi-structured interview was conducted with each participant after the end of the ITE program in order to have access to their sense of progression and factors connected with it.

Moroney et al.'s (2016) findings suggest that both groups, in-career and pre-service teachers were 'open to learning and adaptation'. Although it was not possible to determine whether the pre-service teachers would be able to move to a status of adaptive experts, it was possible to identify the role of the placement tutor as 'a driver of change' (Moroney, et al., 2016, p. 316). Therefore, their study has shed light on factors that both hinder and help the learning of TCs.

The paragraphs below review a series of action-research studies conducted by Marina Orsini-Jones. All of them issued from the same project and there was admitted overlap between the data presented in the different publications, but each publication presented data from different cohorts too. In all cases, the participants were undergraduates in a BA in Modern Languages program, many of whom intend to become language teachers, either of English as a Foreign Language or other European languages as foreign languages in Britain (Orsini-Jones & Jones, 2007; Orsini-Jones, 2008, 2010). The studies can thus be said to have focused on pre-service teachers. The focus of the project has been on investigating grammatical rank scale, or grammatical constituent analysis, as a TC, and facilitating its acquisition through careful scaffolding in a blended-learning environment.

Orsini-Jones and Jones (2007) laid out three goals for their action-research paper. The first was to show that a constructivist assessment task designed to increase motivation and autonomy could promote learning of the target TC. The outcomes of this task were the design of a web site to explain grammatical categories and a presentation of this web site. The second was to show that the virtual learning environment (VLE) can help pre-service teachers overcome their reluctance to reflect on their learning; this VLE included discussion forums where students could discuss their questions and insights about rank scale analysis, as well as online grammar explanations. The third was to show that there can be mismatches between students' self-reported learning of the target TC and their actual performance in grammatical analysis tasks. Through qualitative analysis and the use of quantitative performance data from two cohorts (N=128), they demonstrated that their intervention accomplished the first two goals, and they also built a case for the third goal. In the interviews, many pre-service teachers claimed they had mastered the TC, but performance data showed that they had not. Conversely, many pre-service teachers reported not having mastered the TC, but their performance in the assessment task showed that they in fact had. They concluded that online interaction with peers and mentors facilitated the acquisition of the TC and that qualitative studies based on self-reports needed to be supplemented with performance data.

Orsini-Jones (2008) analyzed the same pre-service teachers but had a different focus: describing in detail the liminal stage that the pre-service teachers went through. In addition to the interview material from the previous study, the author also analyzed pre-service teachers' learning journals and online discussion forums. She found that some pre-service teachers struggled not only with the general concept of rank scale, but also with the concepts for the different parts of speech, especially the concepts of morpheme and clauses; the latter tended to be confused with phrases and vice versa. The author labeled these as 'troublesome components' of the TC and adds that, while some pre-service teachers could identify parts of speech easily, they still had trouble identifying how the connections among them worked to create a sentence. Among the factors hindering their progress were the refusal to engage with new terms and a semantic way of analyzing syntax, their incorrect understanding of grammatical categories (sometimes based on previous schooling), interindividual variation in the kind and quality of previous grammar learning, the leadership shown during groupwork by pre-service teachers with conflicting or incorrect understandings of grammar, not asking instructors for help, and lack of motivation. While only a few pre-service teachers were able to fully cross the threshold, most experienced improvement. The pre-service teachers that crossed the threshold reported that 'the realization that the rank scale unlocked the hidden architecture of a sentence transformed their perception of language learning and language analysis' (pp. 223-224). Nevertheless, the author also found that some pre-service teachers were able to analyze L2 sentences correctly using rank scale analysis but could not successfully analyze sentences in their L1 (English). The author concludes that this finding calls into question the integrative and irreversible nature of the TC in focus.

Orsini-Jones (2010) reported on a new iteration of her action-research cycle, with a different population: 24 self-selected volunteers from a total of 69 students in two cohorts of pre-service teachers majoring in French, Spanish, or English, many of whom planned to become teachers of those languages (EFL in the case of the English majors). As with the two previous studies, this one used a virtual learning environment and a constructivist, collaborative, grammatical analysis task. Changes resulting from previous cycles were a heavier emphasis on and scaffolding of metacognition, peer and mentor tutoring, more varied explanations of troublesome components, and highlighting underlying grammatical principles across the three languages. The study used a mixed-methods approach, with interviews and analyses of the pre-service teachers' test results. The focus was on liminality, identifying barriers and supports to crossing the threshold, and (dis)confirming the nature of the rank scale as a TC. The following troublesome components were identified: complex sentences, clauses, phrases (confusion with clauses), word classification (adverbs and prepositions). Collaborative work, diagnostic tests, tailor-made materials and metacognition activities were found to help. An important finding was that non-British pre-service teachers found grammatical analysis easier, which the author attributed to their more extensive grammar instruction since elementary school as compared with their British peers. The author wondered whether this adds a cultural dimension to the nature of the TC. Clauses, adverbs and prepositions remained troublesome components. Metacognitive scaffolding such as providing samples of reflective discourse were helpful; in particular, many students reported feeling that they knew what to do to improve their understanding of grammar even if they weren't always successful at grammatical analysis. The author interpreted this as an effect of the ability to reflect on the pre-service teachers' readiness to cross the threshold: even if they don't cross it, enhanced metacognition can help them to be ready for 'the ontological shift that can lead to the 'eureka' moment of grasping the concept' (p. 293). As in prior studies, some pre-service teachers were able to analyze rank scale successfully in one language but not in another, which called into question the TC's irreversibility. Nevertheless, the author concluded that rank scale is indeed a TC for linguists 'and, we would add, language teachers 'as it is troublesome, transformative, integrative, and bounded, even if it is not irreversible. The implications of these studies by Orsini-Jones are that a) rank scale is a very difficult concept for language teachers, b) some of its components are more difficult than others and need to be given greater attention, and c) its learning can be facilitated by careful metacognitive scaffolding.

Discussion and conclusion

As seen above, the following TCs have been identified in language teacher education: interlanguage, effective teacher talk, real language use, fostering learner autonomy, and grammatical rank scale (constituent structure). The preferred design used by TC studies has been action research, and the methods have included interviews (with or without stimulated recall) and observations. A feature of all the studies we reviewed is that the identification of the threshold concept in focus in each paper seems to have been driven by an individual author's intuition that a certain disciplinary concept possesses all or some of the features that would make it a threshold concept per Meyer and Land (2003, 2005). When we use the word 'author,' we refer only to the authors of the papers included in this review (i.e., Marina Orsini-Jones, Moisés Perales-Escudero, and so on), not to other authors who have researched the same or similar topics using other lenses, such as language ideologies or attitudes. Each one of these authors has then sought empirical confirmation by implementing some kind of intervention and studying it through action research. Designs involving input from several experts in the field and/or education specialists have been absent so far in the TC published literature. The specific authors of the papers we have reviewed above have also tended not to report whether they consulted the vast literature on teachers' identity, attitudes, beliefs, ideologies and their effects on teaching methods and language practices in order to inform their choice of a concept to probe whether the concept in focus in each of their papers was a TC. Thus, a next and necessary step is to conduct research using such designs and literature reviews since they would help to enhance the rigor and relevance of findings. The existing literature offers plenty of concepts ripe to be interrogated as potential TCs using such methods. Examples include functional grammar, in particular the notion of grammar as a system of communication-motivated choices (Swierzbin & Reimer, 2019), considering linguistic and cognitive aspects when providing corrective feedback (Vásquez & Harvey, 2010; Gómez et al., 2019), seeing language as discourse and seeing language-as-discourse as constitutive of content (Belz, 2005; Burns & Knox, 2005), and transferring phonetics and phonology knowledge to teaching (Gregory, 2005).

Addressing such potential threshold concepts with rigor would help to tackle the field's current need to increase its social relevance. According to Kubanyova and Feriok (2015), one of the ways to address this need involves identifying how teacher education can best promote teacher learning. As established above, a TC approach focuses on enhancing learning by identifying troublesome, transformative concepts and using them explicitly in curricular design. Therefore, it seems ideally poised to address the goal set forth by Kubanyiova and Feriok (2015).

In addition, several features of threshold concepts seem to fit well with the three programmatic directions for language teacher education research advocated by Kubanyiova and Feriok (2015) in order to increase the field's relevance. These directions, or shifts, are 1) studying teacher cognition as 'emergent sense-making in action' (p. 445), which involves focusing on emotions, cognitions and context simultaneously, 2) 'adopting bottom-up approaches to identifying salient dimensions of [pre-service] language teachers' inner lives' (p. 436), and 3) 'recognizing the pivotal role of context in the study of language teacher cognition' (p. 445). With regard to the first direction, we agree with Beaty (2006) that the TC approach is valuable in addressing questions such as 'how shifts in understanding are caught up inextricably with affective factors and with shifts in the learner's identity' (p. xi). As to the second direction, the central focus of threshold concepts on pre-service teachers' experiences constitutes a bottom-up approach as illustrated by the studies reviewed above. Finally, boundedness is a feature of threshold concepts that may help address the third dimension, especially if seen as focused on practice (Brunetti et al., 2014). In particular, TC scholars in language teacher education may need to approach the threshold quality of concepts less as a general feature valid across contexts and more as a context-embedded feature. In other words, it is possible that certain concepts may act as threshold for some groups of pre-service teachers in some contexts at sometimes, but the same concepts may be lacking this threshold quality for other groups, in other contexts at other times. It is also possible that the threshold quality holds generally for other concepts, but this is a matter for empirical research.

Research in threshold concepts in language teacher education offers the potential to explore a little-examined aspect of language teacher identity, namely that which focuses on disciplinary identity. Disciplinary identity refers to a teacher's affinity with one or several of the different disciplines that underpin language teaching (Pennington, 2015). Of course, there are other aspects of teacher identity, such as professional, vocational, sociocultural, global, and local, that have been extensively researched (Pennington, 2015). However, teachers' identity affiliations or disaffiliations with (rather than knowledge of) different bodies of disciplinary knowledge (i.e., cognitive linguistics, Systemic-Functional Linguistics, SLA, psychology, education) have been less researched We think such research is especially important in light of the interdisciplinary, soft-applied nature of language teaching as a field of practice (Pennington, 2015), its recent professionalization in countries such as Mexico (Davies, 2011; Ramírez Romero, 2013; Toledo Sarracino, 2014; Ruiz Esparza Barajas & Lengeling, 2016), and recent concerns about its increasing fragmentation and devaluation, specifically in Mexico (Perales-Escudero, Sánchez Hernández, Lengeling & Ariza Pinzón, 2019; Salas Serrano, 2018).

In particular, Salas Serrano (2018) showed that the Mexican teachers in her sample viewed their professional identity in terms of positive emotional dispositions and skills, rather than knowledge, and perceive that their profession is not valued. There is also evidence that students in undergraduate programs, graduate programs, and even graduates from Master's degree programs see the identity of language teachers as primarily that of an orchestrator of games and a purveyor of fun (Perales-Escudero et al., 2019; García Verdugo, 2019).[1] At the same time, otherwise extremely valuable studies on Mexican ELT teachers' identity (e.g., Crawford, Lengeling, Mora Pablo & Heredia Ocampo, 2014; Lengeling, 2010; Mora, 2017; Mora Pablo, Rivas Rivas, Lengeling & Crawford, 2015) have not focused on the knowledge-identity relationship. We suggest that the ELT profession will not gain the recognition and social relevance it seeks unless it can show specific, concrete ways in which training leads to specialized, technical and distinct ways of conceptualizing and addressing the phenomena targeted by the field. By 'distinct' we mean different from those of general educators (i.e., graduates of general education programs taught in teachers' colleges [Escuelas Normales in Mexico]), linguists, and laypersons. In achieving this ambitious goal, identifying threshold concepts and organizing ELT programs around a threshold concepts approach to deep learning may be of assistance.

In conclusion, we would like to point out that a TC approach can and should extend beyond language teacher education to encompass the experiences of language learners themselves. In other words, as suggested by the work of Orsini-Jones, TCs can be identified in language learning, not only in language teaching. Finally, we suggest that TCs can also be sought in the intersections and interstitial spaces between the experiences of language learners and those of language teachers in real contexts of practice.

References

Abreu, L. (2015). Changes in beliefs about language learning and teaching by foreign language teachers in an applied linguistics course. Dimension, 136'163. http://www.scolt.org/wp-content/uploads/2019/08/Dimension-2015_FINAL_4-29.pdf

Barcelos, A. M. F. (2003). Researching beliefs about SLA: A critical review. In P. Kalaja and A.M.F. Barcelos (Eds.), Beliefs about SLA: New research approaches, (pp. 7-33). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4020-4751-0_1

Barcelos, A. M. F. (2007). Reflexíµes acerca da mudaní§a de crení§as sobre ensino e aprendizagem de línguas [Reflections on change in beliefs about language learning and teaching]. Revista Brasileira de Lingüstica Aplicada, 7(2), 109-138. http://dx.doi.org/10.1590/S1984-63982007000200006

Barradell, S. (2013). The identification of threshold concepts: A review of theoretical complexities and methodological challenges. Higher Education, 65(2), 265'276 https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-012-9542-3

Bartels, N. (2005). Researching applied linguistics in language teacher education. In N. Bartels (Ed.), Applied linguistics and language teacher education, (pp. 1-26). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-2954-3

Beaty, L. (2006). Foreword. In J. H. F. Meyer & R. Land (Eds.), Overcoming barriers to student understanding. Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge (pp. xi'xiii). Routledge.

Belz, J. (2005). Discourse analysis and foreign language teacher education. In N. Bartels (Ed.), Applied linguistics and language teacher education, (pp. 341-364). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-2954-3

Bernstein, B. (1999). Vertical and horizontal discourse: An essay. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 20(2), 157-173. https://doi.org/10.1080/01425699995380

Borg, M. (2005). A case study of the development in pedagogic thinking of a preservice teacher. TESL-EJ,9(2), 1'30. https://www.tesl-ej.org/wordpress/issues/volume9/ej34/ej34a5

Borg, S. (2001). Self-perception and practice in teaching grammar. ELT Journal, 55(1), 21'29. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/55.1.21

Borg, S. (2003). Teacher cognition in language teaching: a review of research on what language teachers think, know, believe, and do. Language Teaching, 36(2), 81-109. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444803001903

Borg, S. (2006). Teacher cognition and language education: Research and practice. Continuum.

Borg, S. (2012). Current approaches to language teacher cognition research: A methodological analysis. In R. Barnard & A. Burns (Eds.),Researching language teacher cognition and practice: International case studies (pp. 11'29). Multilingual Matters.

Brunetti, K., Hofer, A., & Townsend, L. (2014). Interdisciplinarity and information literacy instruction: A threshold concepts approach. In C. O'Mahoney, A. Buchanan, M. O'Rourke, & B. Higgs (Eds.), Threshold concepts: From personal practice to communities of practice. Proceedings of the National Academy's Sixth Annual Conference and the Fourth Biennial Threshold Concepts Conference, Dublin, Ireland, June 27-29, 2012 (pp. 89-93). National Academy for Integration of Research, Teaching and Learning (NAIRTL).

Burns, A. & Knox, J. (2005). Realisation(s): Systemic-Functional Linguistics and the language classroom. In N. Bartels (Ed.), Applied linguistics and language teacher education, (pp. 235-260). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-2954-3

Burns, A., Freeman, D., & Edwards, E. (2015). Theorizing and studying the language-teaching mind: Mapping research on language teacher cognition. The Modern Language Journal, 99(3), 58'601. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12245

Busch, D. (2010). Pre-service teacher beliefs about language learning: The Second Language Acquisition course as an agent for change. Language Teaching Research, 14(3), 318'337. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168810365239

Clark, C. M. & Peterson, P. L. (1986). Teachers' thought processes. In M. C. Wittrock (Ed.), Handbook of research on teaching (pp. 255'296). Macmillan.

Crawford, T., Lengeling, M., Mora Pablo, I., & Heredia Ocampo, R. (2014). Hybrid identity in academic writing: 'Are there two of me?'. PROFILE: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 16(2), 87'100. https://doi.org/10.15446/profile.v16n2.40192

Dankić, I. (2011, May). Student 'resistance' to reflection: Pre-service teacher training at the Mostar University, Bosnia and Herzegovina. Paper presented at 1st International Conference on Foreign Language Teaching and Applied Linguistics, Sarajevo, Bosnia and Herzegovina.

Davies, P. (2011). Three challenges for Mexican ELT experts in public education. In A. R. Duran & R. D. Angel (Eds.), Memorias del XII Encuentro Nacional de Estudios en Lenguas (pp. 21'37). Universidad Autónoma de Tlaxcala. https://doi.org/10.11114/jets.v4i7.1513

Devitt, A. & McKendy, E. (2014). Threshold concepts in language teacher knowledge: Practice versus policy. 2014 American Educational Research Association, Annual Meeting, Philadelphia, Pennsylvania.

Entwhistle, N. (2003). Concepts and conceptual frameworks underpinning the ETL project (Occasional Report 3). Enhancing Teaching-Learning Environments in Undergraduate Courses. https://www.etl.tla.ed.ac.uk/docs/ETLreport3.pdf

García Verdugo, L. (2019). Discursos, prácticas e identidades disciplinares en la escritura de estudiantes de licenciatura y posgrado en Física y Enseñanza de Lenguas Extranjeras [Discourses, practices and disciplinary identities in the writing of undergraduate and graduate students of Physics and Foreign Language Teaching] (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Instituto de Investigación y Desarrollo Educativo-Universidad Autónoma de Baja California, Ensenada, México.

Golombek, P. R. (1998).A study of language teachers' personal practical knowledge. TESOL Quarterly, 32(3), 447'64. https://doi.org/10.2307/3588117

Gómez, L., Hernández, E., & Perales Escudero, M. (2019). EFL teachers' attitudes towards oral corrective feedback: A case study. PROFILE: Issues in Teachers' Professional Development, 21(1), 107-120. doi.org/10.15446/profile.v21n1.69508

Gregory, A. (2005). What's phonetics got to do with language teaching? Investigating future teachers' use of knowledge about phonetics and phonology. In N. Bartels (Ed.), Applied linguistics and language teacher education, (pp. 201-220). Springer. http://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-2954-3

Hammerness, K., Darling-Hammond, L., Bransford, J., Berliner, D., Cochran-Smith, M., McDonald, M., & Zeichner, K. (2007). How teachers learn and develop. In L. Darling-Hammond & J. Bransford (Eds.), Preparing teachers for a changing world: What teachers should learn and be able to do, (pp. 358-389). Wiley and Sons.

Horii, S. Y. (2015). Second language acquisition and language teacher education. In M. Bigelow & J. Ennser'Kananen (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Educational Linguistics (pp. 313-324). Routledge.

Horwitz, E. K. (1985). Using student beliefs about language learning and teaching in the foreign language methods course. Foreign Language Annals, 18(4), 333'340. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1944-9720.1985.tb01811.x

Kamiya, N. & Loewen, S. (2014). The influence of academic articles on an ESL teacher's stated beliefs. Innovation in Language Learning and Teaching, 8(3), 205'218. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/17501229.2013.800077

Kubanyiova, M. (2012). Teacher development in action. Understanding language teachers' conceptual change. Palgrave Macmillan.

Kubanyiova, M. & Feriok, A. (2015). Language teacher cognition in applied linguistics research: Revisiting the territory, redrawing the boundaries, reclaiming the relevance. The Modern Language Journal, 99(3): 435-449. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12239

Land, R., Meyer, J.H.F., & Baillie, C. (Eds). (2010). Preface. Educational futures: Rethinking theory and practice. Threshold concepts and transformational learning, (pp. ix-xlii). Sense Publishers.

Lengeling, M. M. (2010). Becoming an English teacher: Participants' voices and identities in an in-service teacher training course in central México. Universidad de Guanajuato.

Li, L. (2017). Social interaction and teacher cognition. Edinburgh University Press.

Lo, Y.-H. (2005). Relevance of knowledge of second language acquisition: An in-depth case study of a non-native EFL teacher. In N. Bartels (Ed.), Applied linguistics and language teacher education, (pp. 135-158). Springer. https://doi.org/10.1007/1-4020-2954-3

Lyle, J. (2003). Stimulated recall: a report on its use in naturalistic research. British Educational Research Journal, 29(6): 861'878. https://doi.org/10.1080/0141192032000137349

Markham, P., Rice, M., & Darban, B. (2016). ESL teachers as theory makers: A discourse analysis of student assignments in a second language acquisition course. Journal of Language Teaching and Research, 7(2), 233'242. http://dx.doi.org/10.17507/jltr.0702.01

Maton, K. & Doran, Y. J. (2017). Semantic density: A translation device for revealing complexity of knowledge practices in discourse, part 1 ' Wording. Onomázein, Número especial LSF y TCL sobre educación y conocimiento, 46'76. https://doi.org/10.7764/onomazein.sfl.03

Meyer, J. H. F. & Land, R. (2003). Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge: Linkages to ways of thinking and practising within the disciplines. In C. Rust (Ed.), Improving student learning ' Ten years on. OCSLD. https://www.dkit.ie/system/files/Threshold_Concepts__and_Troublesome_Knowledge_by_Professor_Ray_Land_0.pdf

Meyer, J. H. F., & Land, R. (2005). Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge (2): Epistemological considerations and a conceptual framework for teaching and learning. Higher Education, 49(3), 373'388. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10734-004-6779-5

Meyer, J. H. F., & Land, R. (2006). Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge: An introduction. In J. H.F. Meyer and R. Land (Eds.), Overcoming barriers to student understanding: Threshold concepts and troublesome knowledge,(pp. 3-17). Routledge.

Mora, A. (2017). Writer identity construction in Mexican students of applied linguistics. Cogent Education, 4, 1-13. https://doi.org/10.1080/2331186X.2017.1365412

Mora Pablo, I., Rivas Rivas, L. A., Lengeling, M. M., & Crawford, T. (2015). Transnationals becoming English teachers in Mexico: Effects of language brokering and identity formation. GIST Education and Learning Research Journal, 10, 7-28. https://doi.org/10.26817/16925777.264

Moroney, D., McKendry, E., & Devitt, A. (2016). Knowledge, belief and practice in language teacher education: Integration and implementation of threshold concepts over a teaching career. In R. Land, J. H. F. Meyer, & M. T. Flanagan (Eds.), Threshold concepts in practice (pp. 309'320). Sense Publisher.

Orsini-Jones, M. (2008). Troublesome language knowledge: Identifying threshold concepts in grammar learning. In R. Land, J. H. F. Meyer, & J. Smith (Eds. ), Threshold concepts within the disciplines (pp. 213-226). Sense Publisher.

Orsini-Jones, M. (2010). Troublesome grammar knowledge and action-research-led assessment design: Learning from liminality. In J. H. F. Meyer, R. Land, & C. Baillie (Eds.), Threshold concepts and transformational learning (pp. 281'299). Sense Publisher.

Orsini-Jones, M., & Jones, D. (2007). Supporting collaborative grammar learning via a virtual learning environment. Arts & Humanities in Higher Education, 6(1), 90-106. https://doi.org/10.1177/1474022207072230

Pajarés, M. F. (1992). Teachers' beliefs and education research: Cleaning up a messy construct. Review of Educational Research, 62(3), 307-332. https://doi.org/10.3102/00346543062003307

Pennington, M. C. (2015). Teacher identity in TESOL: A frames perspective. In Y. L. Cheung, S. Ben Said & K. Park (Eds.), Advances and current trends in language teacher identity research (pp. 32-55). Routledge. https://doi.org/10.4324/9781315775135

Perales-Escudero, M. D. (2017). Conceptos umbrales y conceptos de trayectoria: El caso de los conceptos de interlengua y error en la formación de lingüistas aplicados y profesores de lenguas [Threshold concepts and pathway concepts: The case of interlanguage and error in the training of applied linguists and language teachers]. In F. Encinas (Ed.), Escritura y desarrollo cognitivo en un mundo intertextual: Diálogos con la obra de Charles Bazerman (pp. 123'141). Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla.

Perales-Escudero, M.D., Sánchez Hernández, V., Lengeling, M., & Ariza Pinzón, V. (2019, March). Scholarship, disciplinarity, and literacy in EFL teacher education. In V. Hernández Sánchez (Chair), Scholarship, disciplinarity, and literacy in EFL teacher education [Panel] presented in the 2nd Congreso Internacional de Formadores en Enseñanza de Lenguas, Benemérita Universidad Autónoma de Puebla.

Posner, G. J., Strike, K. A., Hewson, P. W., & Gertzog, W. A. (1982). Accommodation of a scientific conception: Toward a theory of conceptual change. Science Education, 66(2), 211'27. https://doi.org/10.1002/sce.3730660207

Ramírez Romero, J. L. (2013). Una década de búsqueda: Las investigaciones sobre la enseñanza y el aprendizaje de lenguas extranjeras en México (2000-2011) [A decade of inquiry: Research on foreign language teaching and learning in Mexico (2000-2011)]. Pearson.

Razfar, A. (2012). Narrating beliefs: A language ideologies approach to teacher beliefs. Anthropology and Education Quarterly, 43(1), 61-81. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1548-1492.2011.01157.x

Ricketts, A. (2010). Threshold concepts: 'loaded' knowledge or critical education? In J. H. F. Meyer, R. Land, & C. Baillie (Eds.), Threshold concepts and transformational learning. (pp. 45'60). Sense Publisher.

Ruiz Esparza Barajas, E. & Lengeling, M. M. (2016). Histories of English as a Foreign Language Teacher Development in Mexican Public Universities. University of Sonora.

Salas Serrano, L. A. (2018). Defensa de la profesión: El discurso de una CoP de maestros de inglés [Defending the profession: The discourse of a community of practice of EFL teachers]. Lenguas en Contexto, 9, 69'80. http://www.facultaddelenguas.com/lencontexto/app/revista/DIGITAL/9sup/revista-9sup.pdf

Sandoval Cruz, R. I., Navarro Rangel, Y., & González Calleros, J. M. (2019, June). Variación de experiencias de aprendizaje colaborativo en un contexto de b-learning [Variation of collaborative learning experiences in a b-learning context]. In J. M. González Calleros (Chair), V Jornadas Iberoamericanas de Interacción Humano-Computador 2019, paper presentedat the 2019 meeting of the Jornadas Iberoamericanas de Interacción Humano-Computador, Puebla, Mexico.

Schwartzman, L. (2010). Transcending disciplinary boundaries: A proposed theoretical foundation for threshold concepts. In J. H. F. Meyer, R. Land, & C. Baillie (Eds.), Threshold concepts and transformational learning (pp. 21'44). Sense Publishers.

Selvi, A. F. & Martin-Beltrán, M. (2016). Teacher-learners' engagement in the reconceptualization of second language acquisition knowledge through inquiry. System, 63, 28-39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2016.08.006

Shanahan, M., Foster, G., & Meyer, J. H. F. (2010). Threshold concepts and attrition in first-year economics. In J. H. F. Meyer, R. Land, & C. Baillie (Eds.), Threshold concepts and transformational learning (pp. 207'226). Sense Publishers.

Skinner, B. (2017). Effective teacher talk: A threshold concept in TESOL. ELT Journal, 71(2), 150'159. https://doi.org/https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccw062

Song, S. Y. (2015). Teacher beliefs about language learning and teaching. In M. Bigelow & J. Ennser'Kananen (Eds.), The Routledge Handbook of Educational Linguistics (pp. 263'275). Routledge.

Svalberg, A. M.'L. (2015). Understanding the complex processes in developing student teachers' knowledge about grammar. Modern Language Journal, 99(3), 529'545. https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12241

Swierzbin, B. & Reimer, J. (2019). The effects of a functional linguistics-based course on teachers' beliefs about grammar. Language Awareness, 28(1), 31-48. https://doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2019.1598423

Toledo Sarracino, D. G., (Coord.) (2014). Panorama de la enseñanza de lenguas extranjeras en México. Universidad Autónoma de Baja California.

Valencia Cabrera, M. (2017). The construction of teacher candidates' imaginaries and identities in Canada, Colombia, and Chile: An international comparative multiple narrative case study (Doctoral dissertation). University of Toronto. http://hdl.handle.net/1807/80946

Vásquez, C., & Harvey, J. (2010). Raising teachers' awareness about corrective feedback through research replication. Language Teaching Research, 14(4), 421-443. https://doi.org/10.1177/1362168810375365

Walsh, S. (2006). Talking the talk of the TESOL classroom. ELT Journal, 60(2): 133'41. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/cci100

Weekly, R. (2018). 'English is a mishmash of everything': Examining the language attitudes and teaching beliefs of British Asian multilingual teachers. Critical Inquiry in Language Studies, 16(3). 178-204. https://doi.org/10.1080/15427587.2018.1503936

Young, A. S. (2014). Unpacking teachers' language ideologies: Attitudes, beliefs, and practiced language policies in schools in Alsace, France. Language Awareness, 23(1-2), 157-171. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/09658416.2013.863902

[1] As an aside, we note that this fun-focused identity contrasts sharply with that of many of the Canadian, Chilean and Colombian English teachers in Valencia Cabrera (2017), who tend to see teachers as 'beings whose job is to make students suffer and to eradicate fun' (p. 218) and who are themselves deprived of the possibility to have fun.