Introduction

Traditionally, literacy has been conceptualized as monolithic, a set of universal, decontextualized cognitive skills, usually taking the form reading and writing (Auerbach, 1995; Kalantzis & Cope, 2000). Street (1984) called this traditional conception of literacy, autonomous literacy, and challenged it by introducing the alternative concept of ideological literacy, which views literacy in terms of concrete social practices and the ideological positions that are embedded within them. From this perspective, literacy is no longer viewed as something possessed as a skill, but something done or performed within particular sociocultural contexts, which has led to the concept of multiple literacies (Cope & Kalantzis, 2000; Barton, Hamilton, & Ivanic, 2000). This model of literacy is often referred to as a social practice model of literacy, largely developed under the aegis of the New Literacy Studies (Gee, 2008; Street, 1993). Such a model is critical in that it recognizes literacy as a technology that cannot be extricated from the structures of power in which it always operates (Brandt & Clinton, 2002). However, conceptualizing literacies as contextualized social practices, in some ways, obfuscates what ‘being literate’ actually entails. As such, further discussion of how multiple literacies may be conceptualized merits further discussion.

Attempting to further develop the social practice model of literacy, Gee (2008) conceptualizes a model of multiple literacies as distinct Discourse(s). Gee (2008) makes a distinction between Discourse (with a capital “D”), which refers to Discourses that are associated with the social practices of a particular community of practice and discourse (with a lower-case “d”) as a general, encompassing category that all Discourses fall under. Gee (ibid., p. 155) explains that:

a Discourse is composed of distinctive ways of speaking/listening and often, too, writing/reading coupled with distinctive ways of acting, interacting, valuing, feeling, dressing, thinking, believing, with other people and with various objects, tools, and technologies, so as to enact specific socially recognizable identities engaged in specific socially recognizable activities.

Gee’s definition of Discourse(s) (i.e. literacies) is particularly significant due to its emphasis on multimodal resources such as “objects, tools, and technologies” as well as a focus on values, beliefs, and (inter)actions, all of which come together at specific sites to engender recognizable identities engaged in social action. Such a broad definition of literacies takes into consideration the multimodal, action-oriented, and social nature of ‘being literate’ (or not) within a particular affinity group (Bhatia, 2004). A Discourse, then, involves being—doing a particular identity within a situated social context (Gee, 2008), which may include, for example, being—doing an English teacher or English learner. According to Gee (2008), “literacy is always plural” (p. 176) because he defines literacy as, “[m]astery of a secondary Discourse” (p. 176), which he distinguishes from a primary Discourse. A primary Discourse is acquired within a person’s “primary socializing unit early in life” and provides a person with an “enduring sense of self and sets the foundations of our culturally specific vernacular language” (ibid., p. 156). On the other hand, secondary Discourses are acquired later in life “within a more public sphere than our initial socializing group” such as “religious groups, community organizations, schools, businesses, or governments” (ibid., p. 157) and “share the factor that they require one to communicate with non-intimates” (Gee, 1998, p. 56). As defined above, there are as many literacies as there are secondary Discourses. Importantly, however, Gee (ibid.) points out that because “Discourses are intimately related to the distribution of social power and hierarchical structure in society, control over certain Discourses [dominant Discourses] can lead to the acquisition of social goods (money, power, status) in a society” (p. 52). Mastery of a dominant Discourse can be thought of as a dominant literacy (ibid., p. 56), which are privileged in mainstream societies.

A major criticism of a social practice model of literacy stems from the notion that it “exaggerat[es] the power of local contexts to set or reveal the forms and meanings that literacy takes” (Brandt & Clinton, 2002, p. 338). Brandt and Clinton (2002) propose instead that “literacy is neither a deterministic force nor a creation of local agents. Rather it participates in social practices in the form of objects and technologies” (p. 338), which have “a capacity to travel…to stay intact…to be visible and animate outside the interactions of immediate literacy events. These capacities stem from…its material forms, its technological apparatus…its (some)thing-ness” (p. 344). Here, literacy in its material forms is recognized as a social actor which can mediate interactions with other times and places (Kress, 2000; Brandt & Clinton, 2002). Just as human agents mediate literacy practices, often recrafting and imbuing them with local meanings in order to resist their hegemonic currents and fulfill local needs, objects can also be “active mediators—imbuing, resisting, recrafting” (Brandt & Clinton, 2002, p. 346). By recognizing the role that objects play in social interaction, Brandt and Clinton (2002) suggest that we can bridge “the macro and micro, agency and social structure, the local and the global” (p. 346). Hence, this perspective of literacy emphasizes the need to account for the role that imported material Discourses (Gee, 2008) play in the dialectic process of glocalization (see Kumaravadivelu, 2008), stressing that “figuring out what things are doing with people in a setting becomes as important as figuring out what people are doing with things in a setting” (Brandt & Clinton, 2002, p. 348).

With the issues discussed above in mind, the current article presents a partial report from a larger study that analyzed the manner in which a group of classroom participants (teacher and learners) utilize distinct literacies in order to navigate through the diverse situations encountered within an EFL classroom lesson. The larger study performed a multimodal, critical classroom discourse analysis (Jewitt, 2008; Kumaravadivelu, 1999) in a lower-intermediate level EFL classroom. The study took place in a language faculty of public university in Central Mexico. The language faculty’s primary function is to prepare future teachers of EFL to give classes in the Mexican context. The study sought to explain classroom culture and the multiple literacies required to successfully participate within this often ritualized environment (Prabhu, 1992). Through a detailed analysis of interactional patterns, the different roles and identities that are enacted within the classroom context are explored, providing insights into how the classroom as a culture and its multimodal interactions provide differentiated opportunities for learning (Gee & Green, 1998). Particular attention was given to the manner in which classroom artifacts, especially the EFL textbook, influence classroom practices as well as how classroom participants strategically utilize these artifacts in order to accomplish their particular goals within the classroom culture (Green & Weade, 1990). In order to explore these issues, the larger study addressed the following research questions:

- What literacies are enacted by classroom participants during the lesson under investigation in order to accomplish their social goals?

- How does the classroom context support and constrain particular literacy events?

- How do literacy events enable participants to establish classroom roles and identities during the lesson under investigation?

- What classroom rituals (or moves) are followed during the lesson under investigation?

In addressing these questions, the larger study examined multiple data sources including video footage of an EFL lesson, transcripts of the lesson, photographs, interviews, field notes and classroom artifacts. Due to constraints on space, the current article cannot provide a complete account of the data analysis. As such, only a small sample of literacy events that occurred during the EFL lesson under investigation will be presented, and the conclusions presented will be hedged accordingly. Constraints on space also prevent a complete review of the relevant academic literature which might provide a thorough backdrop for the analyses and discussion presented. Therefore, brief reviews of relevant literature will be integrated into the different sample analyses presented in the article. However, there are certain theoretical concepts that are of particular importance to this investigation, meriting a brief review of relevant academic literature below.

Multimodal critical classroom discourse analysis

Kumaravadivelu (1999, p. 454) reminds us that

classroom is the crucible where the prime elements of education—ideas and ideologies, policies and plans, materials and methods, teachers and the taught—all mix together to produce exclusive and at times explosive environments that might help or hinder the creation and utilization of learning opportunities.

Such a characterization of the classroom makes “the task of systematically observing, analyzing, and understanding classroom aims and events…central to any educational enterprise” (ibid., p. 454) Gee and Green (1998) point out that by studying the discursive activity within classrooms, “researchers have provided new insights into the complex and dynamic relationships among discourse, social practices and learning” (p. 119), which has increased understandings of how:

knowledge constructed in classrooms…shapes, and is shaped by, the discursive activity and social practices [or literacies] of members; patterns of practice simultaneously support and constrain access to the academic content of the ‘official’ curriculum; and how opportunities for learning are influenced by the action of actors beyond the classroom setting (e.g. school districts, book publishers, curriculum developers, legislators, and community members) (p. 119).

Jewitt (2008) adopts a similar view while discussing the importance of multimodality within a framework of critical classroom discourse analysis (CCDA). Multimodality refers to the manner in which meanings are made and interpreted “through the situated configurations across image, gesture, gaze, body posture, sound, writing, music, speech, and so on” (ibid, p. 246). Jewitt (2008) points out that “from decades of classroom language research, much is known about the semiotic resources of language; however, considerably less is understood about the semiotic potentials of gesture, sound, image, movement and other forms of representation” (p. 246). This paucity of research on multimodal classroom literacy practices is of consequence because mode can affect both what meanings are available within the classroom context as well as how those meanings are realized (Kress, 2000). This leads Jewitt (2008) to claim that,

to better understand learning and teaching in the multimodal environment of the contemporary classroom, it is essential to explore the ways in which representations in all modes feature in the classroom…and the learning potentials of teaching materials and the ways in which teachers and students activate these through their interaction in the classroom (pp. 241-2).

Gee and Green (1998) propose that when performing CCDA, the classroom must be viewed “as a type of community of practice” (p. 148) where “members…are continually defining and redefining what counts as community through the norms and expectations, roles and relationships, and rights and obligations constructed” (p. 148; also see Luke, 1995; Wenger, 1998). Within such communities of practice “individual members are afforded access to particular events and spaces; thus, they have particular opportunities for learning and acquiring the social and cultural processes and practices of group membership” (Gee & Green, 1998, p. 148). Gee and Green (1998) point out that within classroom communities, “members have agency and thus take up, resist, transform, and reconstruct the social and cultural practices afforded them in and through the events of everyday life” (p. 148), and the manner in which classroom participants practice such agency (or not) is an important focus of this study.

The characterization of classrooms presented above places demands on what CCDA should entail. According to Gee and Green (1998; but also see Kumaravadivelu, 1999), CCDA should address:

The moment-by-moment, bit-by-bit construction of texts (oral and written), the chains of concerted actions among members, the role of prior and future texts in connecting these ‘bits of life,’ and what members take from one context to use in another…[in order to]…build a grounded view of the cultural models, social practices, and discourse practices that members draw on (p. 149)

An approach to CCDA, as discussed above, would optimally involve longitudinal, ethnographic study, which is what Gee and Green (1998) call “the ideal case” (p. 149). However, they go on to claim that “it is possible to examine a ‘slice of life’ from this perspective to obtain an emic perspective on social participation” (p. 149) within a given classroom. Due to time and space constraints, this “slice of life” approach to CCDA was adopted for the current study as a single lesson is the object of analysis.

The classroom as culture

Central to this investigation’s approach to the study of literacy practices during a language lesson is the view of the classroom as culture (Breen, 2001; Green & Weade, 1990). The classroom is a social situation (Goffman, 1964) that people enter into for a particular period of time for particular purposes, and assume a set of (often asymmetrical) institutional roles (Breen, 2001; Prabhu, 1992). It is a social contract that entails particular rights and obligations as participants construct life together over time (Prabhu, 1992; van Lier, 2001). The various formations of social encounters that members engage in (whole class; small group; teacher/student; student/student; student/group) establish “patterned ways of acting and interacting together” (Green & Weade, 1990, p. 328) and “cultural rules establish how individuals are to conduct themselves, and…socially organize the behavior of those in the situation (Goffman, 1964, p. 135). Prabhu’s (1992) observations about the culturally organized, ritualistic and multimodal nature of the language lesson are worth quoting at length:

the ritualisation may or may not take the form of dress regulations, standing up to show respect, the use of honorifics, first names or last names, not speaking unless asked to, procedures for assignment and submission of work, procedures for punishment and reward, opening and closing moves for the lesson as a whole or for any phase of it, and so on; but there is at least a set of shared notions about the different phases of a lesson, legitimate and deviant behaviour, the extent of teacher’s authority and learner’s right, and duties and obligations on both sides (p. 228).

In other words, over time, classrooms develop into communities of practice (Gee & Green, 1998; Wenger, 1998) and construct cultural knowledge about “what to do (say), to (with) whom, when, where, under what conditions, and for what purpose” (Green & Weade, 1990, p. 328). As such, the group develops a common cultural model (Gee, 2008; Gee & Green, 1998) for guiding interpretations about what is possible and “how actions, interactions and artifacts that comprise life in this social group will be perceived” (Green & Weade, 1990, p. 328). Importantly, because the norms of a classroom are socially constructed within asymmetrical communities (Breen, 2001), access to cultural knowledge is unequal and contingent on opportunities for participation in valued social practices (Gee & Green, 1998). This adds heterogeneity to any community of practice as subcultures emerge and develop alternative ways of engaging in life within that group (ibid., 1998, p. 328).

Classroom communication

Classrooms are environments rich in multimodal communication where teachers and students make meanings in order to construct classroom life. The purpose of exploring classroom communication, in this research, is to shed light on what literacies classroom participants need in order to participate in the social events of the classroom. This is of consequence, as Barnes (1976) points out, because:

a curriculum as soon as it becomes more than intentions is embodied in the communicative life of an institution, the talk and gestures by which pupils and teachers exchange meanings…in this sense curriculum is a form of communication…we cannot make a clear distinction between the content and the form of the curriculum, or treat the subject matter as the end and the communication as no more than a means. The two are inseparable (p. 14).

Freebody (1991a) makes a similar point, stating that “regardless of our hopeful curriculum innovations and changing policies, the lived curriculum for the student has more to do with how the classroom operates as a participation system than with the packages or the rhetoric of curriculum-commodity-consumption” (p. 174). van Lier (2001) also recognizes the classroom as an “institutional setting [that] constrains the types of talk that can occur within its domain” (p. 90), making “the kinds of interaction the classroom permits…of great importance to research” (ibid., p. 90). The section that follows, then, will examine issues related to communication and participation structures within the classroom.

The three part exchange (initiation-response-feedback)

The teaching exchange is one of the most frequently occurring types of classroom communication, and is characterized by its three-part cycle: initiation, response, feedback (Freebody, 1991; van Lier, 2001). In this cycle, the teacher initiates (usually with a question), the student responds (normally with a declarative), and the teacher provides feedback (most commonly as an evaluation). Freebody (1991) claims that “the centrality of the role of the three-part structure as the ‘driving engine’ of classroom talk is a finding that enjoys striking prevalence in most systematic varieties of classroom research” (p. 73). van Lier (2001) agrees, emphasizing the versatility of the initiation-response-feedback (IRF) format since its pedagogic potential “occupies a continuum between mechanical and demanding” (p. 94) as teacher questions may place a range of demands on learners that include: recitation, display, cognition and/or precision (ibid.). Such wide ranging versatility “attests to the care with which teachers and students need to attend to one another in order to take part in the lesson” (Freebody, 1991, p. 73), and this is particularly true in the case of EFL lessons where classroom communication is commonly strained.

A “central feature of IRF is that the teacher is unequivocally in charge” (van Lier, 2001, p. 95) since they are always in control of the initiating and closing sequences, “making it extremely hard, if not impossible, in the IRF format for the student to ask questions, to disagree, to self-correct, and so on” (ibid., p. 95). As such, the IRF format allows teachers to structurally and functionally control the classroom discourse (ibid., p. 96) as they construct what is essentially a univocal exposition (Hargreaves, 1984). Goffman (1981) describes such exchange sequences as “not a state of talk but a state of inquiry” (p. 142). Barnes (1976) also questions the communicative authenticity of such exchanges, pointing out that a large part of learners’ time in school “is spent feeding back to teachers what the teachers have already given out…[they] communicate to the teacher that they are obedient pupils, that they ‘know the answers’”(p. 62). van Lier (2001) sums up the discussion succinctly:

In terms of communication, control, initiative, meaning creation and negotiation, message elaboration, and a number of other features characteristic of social interaction, the learner’s side of the IRF interaction is seriously curtailed.

The role of classroom artifacts in realizing social practices

Of particular relevance to the current study is the manner in which human participants draw upon material objects in order to realize social practices during classroom interactions. This study recognizes cultural artifacts within the classroom setting as social actors which can mediate interactions (Brandt & Clinton, 2002; Kress, 2000). Jewitt (2008) points out that “teacher’s and students’ interaction with the materiality of modes (an inextricable meshing of the physical materiality of a mode and its social and cultural histories)…shape the production of school knowledge” (p. 256). In fact, the strategic use of classroom displays, space, furniture and artifacts may actually realize versions of school subjects (ibid., 2008, p. 249). Baldry and Thibault (2006) make this particularly clear when claiming that the physical object “is itself a meaningful semiotic artifact; it has typical socially recognized uses and the participant roles that these entail. Its size, shape and colour, together provide cues as to how it is to be interpreted as a certain kind of social artifact which is imbued with social significance” (p. 176). It becomes important then to investigate what kinds of cultural artifacts are legitimated in different classroom spaces (Baldry & Thibault, 2006; Gee & Green, 1998; Jewitt, 2008).

Sample of analyses from the classroom lesson

The following sections provide samples of analyses of literacy events from the classroom lesson under investigation. Each sample analysis first presents a brief overview of the literacy event under analysis. Each literacy event is represented by four photographic images that were extracted from video footage of the lesson in order to capture the multimodal interactions that took place during the event, and are accompanied by transcriptions of the verbal interactions. These images are sequentially arranged according to the default Western reading path (right to left/top to bottom) (Kress & van Leeuwen, 2006). The following excerpts of literacy events were selected in order to demonstrate the range of literacies that were enacted and interpreted during the lesson under investigation.

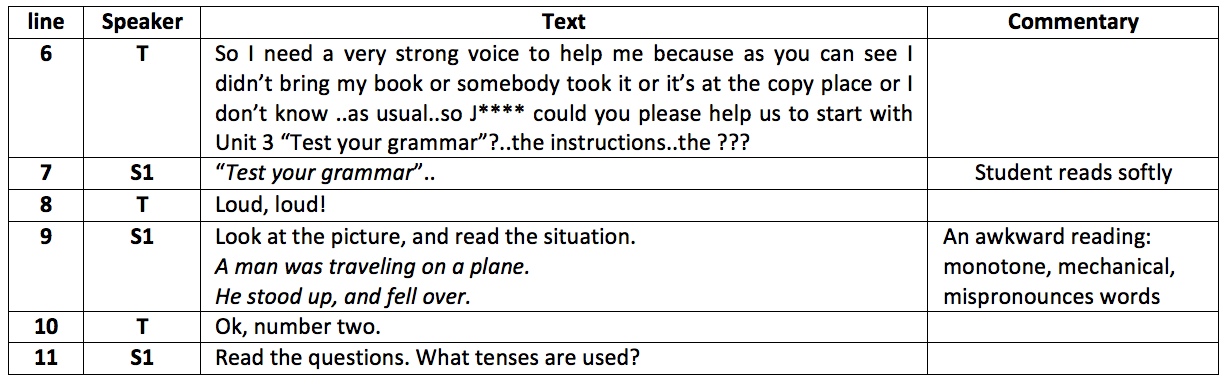

Animating the textbook

Below, Figure 1 depicts various moments of a literacy event that involved the teacher drawing the students’ attention to an activity within their textbook. This was the first activity of the classroom lesson. The textbook activity required students to identify various verb tenses in sentences. The teacher begins by asking a student to read the instructions for the activity. He then moves into an IRF exchange, eliciting the correct answers for the activity from the group as a whole. This literacy event (Fairclough, 1992) and the particular moments depicted in the figure are discussed further below.

Figure 1: Animating the textbook

Table 1: Animating the textbook

The first image above shows the teacher engaged in a deictic gesture co-occurring with speech (Norris, 2004). The gesture also functions as a speech act (Searle, 1969), ‘designating’ a student to read the instructions for Task 1 (see line 6, excerpt 1 above). The student complies, reading the textbook language slowly in a monotone, soft voice (see lines 7-11, excerpt 1 above). It is clear from the student’s prosody (Gumperz, 1982) that he is only animating the textbook, taking no responsibility for the unfamiliar words he speaks (Goffman, 1981). The gaze of the surrounding students makes clear that the textbook, not the student, has the floor (Goffman, 1981). All eyes are focused on the textbook page, whose language is being interposed into the classroom environment with the help of a human host. Lemke (2001) calls such textbook discourse, external text dialog, claiming that functional roles in classroom dialogue that are normally filled by human participants can be filled by imported texts. In Bakhtin’s (1981) terms, this is direct quotation (Kamberelis & Scott, 1992), which implies that the speaker is not at all invested in the words s/he speaks. It could be argued that the student animator is distancing himself from these words by employing a prosodic strategy since he is not reading them under his own volition. It may be just as likely, however, that he has not mastered the literacy of being—doing an English student sufficiently to manage the unfamiliar discourse of the textbook (Gee, 2008; Bhatia, 2004).

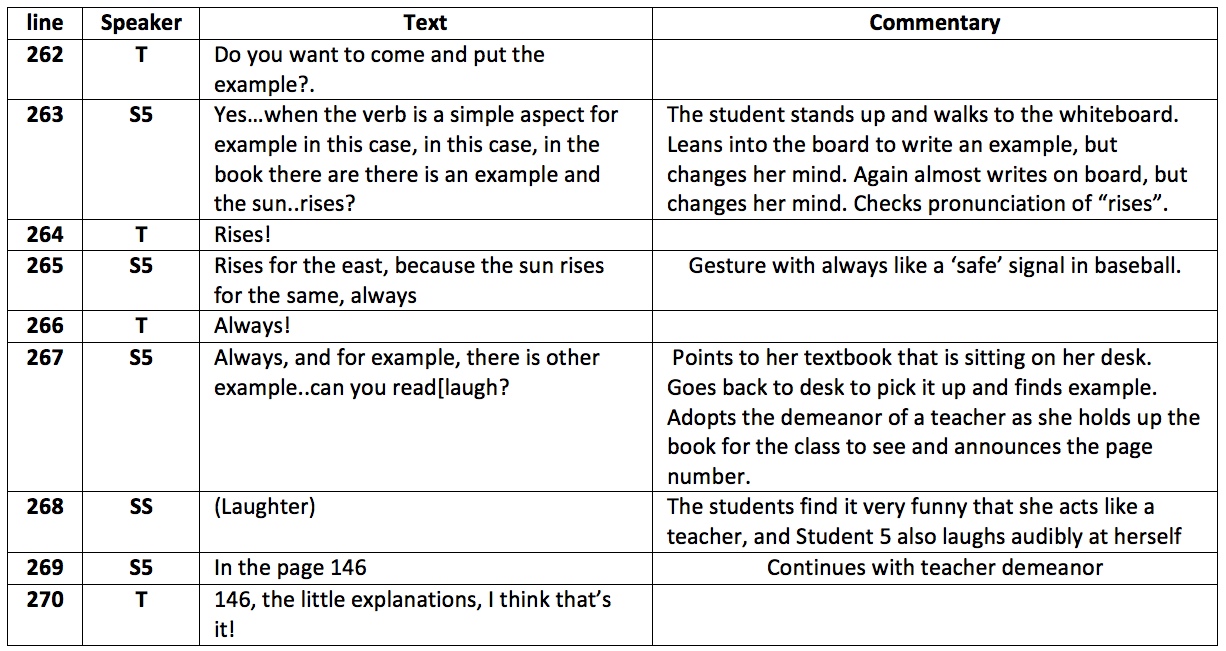

Table 2: IRF: the three part exchange

The third picture in figure 1 above depicts the teacher after he has taken over the floor (Goffman, 1981) and transformed the activity into an IRF exchange between himself and the entire class (see line 12-20, excerpt 2 above). The exchange never places demands on the learners beyond the level of recitation and display (van Lier, 2001) as learners are instructed to either read instructions or display knowledge about narrative tenses. The agility with which the teacher and students engage in the IRF format demonstrates that this is a ‘game’ (Barnes, 1976) that they are familiar with as they swing into the communication pattern without missing a step. The teacher is employing an iconic gesture (Norris, 2004) by holding up two fingers, which is co-occurring with speech as he says the words, “number two” with the rising intonation of a question. This gesture simultaneously functions as a deictic speech act as it designates a particular student to answer the question. The cup of coffee in the teacher’s hand is also salient, a privilege set aside exclusively for him and endowing him with symbolic capital (Bourdieu, 1991). In the fourth image, the teacher has taken up a relatively closed posture (Norris, 2004), positioning one hand on his hip while the other crosses in front of his body. In Mexico, this body positioning is indicative of a serious emotional state, and in this case, it seems to complement the teacher’s role as ‘evaluator’ in the IRF exchange (van Lier, 2001). This stance, in combination with the coffee cup, conveys to his addressees that he is speaking as a principal (Goffman, 1981), with all the institutional authority that accompanies his role as teacher. This literacy event testifies to the vast amount of multimodal activity that is constantly occurring in a multifarious manner within any classroom setting. In only 2 minutes and 37 seconds, various human classroom participants appropriated distinct roles/identities, including: students as reciters, knowers, and (non)participators; teacher as designator, evaluator, institutional representative, and authority. The textbook was given voice, and a host of modal resources were employed in order to realize these social practices (or literacies). The excerpt demonstrate the complex system of literacy options that are available for classroom participants to enact within the classroom context as well as the complex manner in how they may be enacted (Jewitt, 2008).

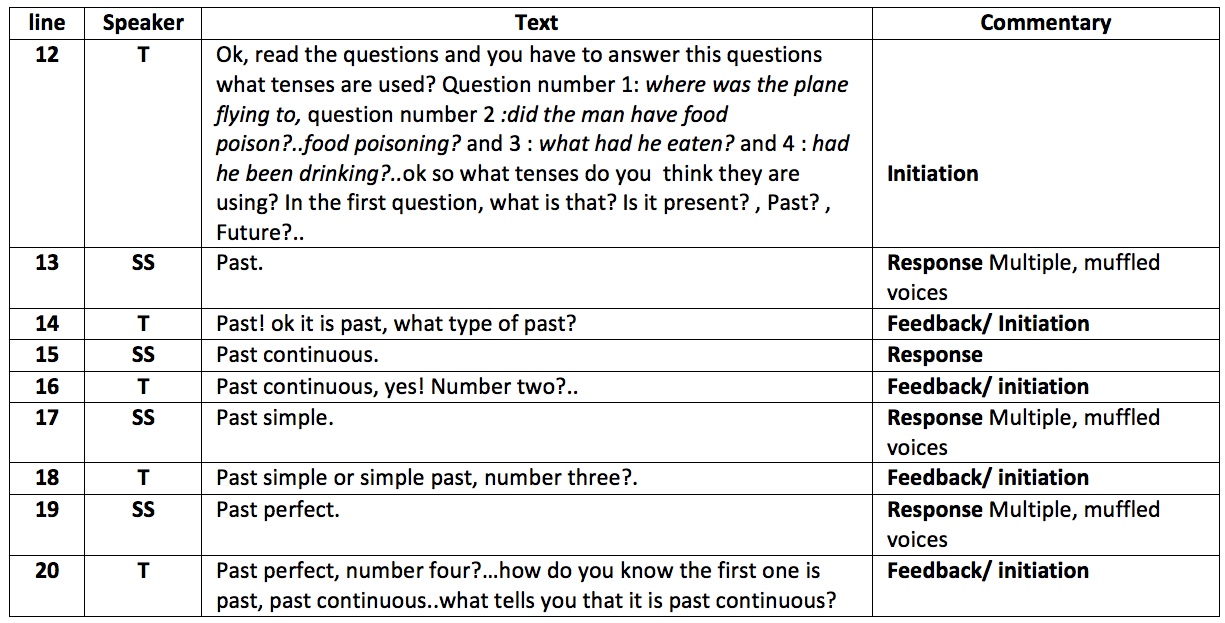

Questioning/appealing to authority

Below, Figure 2 depicts various moments of a literacy event in which the normal flow of an IRF exchange gets interrupted. This interruption causes a disturbance in the routine, ritualized nature of the classroom culture. The point of contention between the teacher and student who interrupts the IRF exchange is over the correct answer within a textbook activity. In this literacy event, we see the teacher’s authority as “Knower” called into question as the student appeals to the authority of the text book in order to provide support for her disagreement. Further discussion is provided below.

Figure 2: Questioning/appealing to authority

The first image from Figure 2 depicts Student 5 immediately after she provides a response to an IRF sequence that does not conform to group opinion (see line 255, excerpt 3). It is worth pointing out that Student 5’s nonconformist response, “no”, was not overly assertive in regard to volume, stress, pitch or tone (Gumperz, 1982); nonetheless, it seemed to ring out like a dissonant note within the group’s harmonizing chord. The teacher immediately responds with his first call for precision, the most demanding end of the IRF continuum (van Lier, 2001), by asking, “why not?”. As seen in the first image above, Student 5 becomes quite nervous, placing her hand on her head as she attempts an explanation (see lines 257-259). In the meantime, the teacher has taken up a strikingly similar posture to the final image of figure 1, when he overtly adopted the role of evaluator/ principal (Goffman, 1981; van Lier, 2001). In this case, his show of institutional authority is probably somewhat defensive (Baldry & Thibault, 2006) as Student 5 is indirectly (and unknowingly; see below) challenging his ‘teacher-as-knower’ role (Breen, 2001). The challenge becomes particularly threatening as she appeals to the authority of the textbook in line 259, deferring the responsibility to explain and illustrate (van Lier, 2001) to Headway’s grammar appendices. In the third image, Student 5 recalls the metalanguage for which she is searching, and in a ‘eureka moment’ points to the teacher and exclaims, “It’s the simple aspect” (see line 261). She is using the gesture to signal her willingness to turn over the floor (Goffman, 1981), fully expecting the teacher to bestow a positive evaluation upon her as if she were engaged in a typical IRF exchange. Student 5 reported that she expected the teacher to respond positively to her participation in an informal interview when she said, “I saw the grammar explanation at the end of the book. I thought the teacher understood me. I think I didn’t understand though.”However, at the moment of the exchange, it seems that Student 5 was caught in a frame mismatch (Goffman, 1997), perceiving the moment completely differently from the teacher and her fellow students. Having contradicted the teacher twice in less than a minute, the rest of the group clearly believe that she has violated the classroom norms, as demonstrated by their thrilled facial expressions, some of whom are focusing their gaze on Student 5, while others focus on the reaction of the teacher (see final image of figure 2 above).

Table 3: Textbook as authority

The teacher’s reaction is quite unexpected, and is discussed in section 3.3 below. The brief exchange up to this point, however, warrants reflection, particularly in regard to the roles that different participants appropriate and how quickly a lesson can suffer a major cultural disturbance due to a moment of unintentional discord that interrupts a routine that van Lier (2001) describes as “mechanical” (p. 94). Student 5 is the first student to author (Goffman, 1981) her own words in the lesson, which means that she constructs creative and original ideas. She appropriates the voice (Bakhtin, 1986) of the textbook, and even defers responsibility to it at one point, but she is not limited to direct quotation and imitation (Kamberelis & Scott, 1992). If fact, she is able to disagree with the teacher by voicing the discourse of the textbook in a manner that combines varying degrees of direct quotation, imitation and her personal stylization. During this process, the interaction is transformed from teacher-whole group to teacher-student, with Student 5 taking equal control of the exchange. The other learners present become disbelieving bystanders (Goffman, 1981) as the usual social conventions that govern classroom life are flouted. Prabhu’s (1992) observation seems relevant:

The more recurrent the encounter, and the more numerous its participants, the greater need for a shared routine and a shared set of expectations. It is only with some notion of where one belongs and where others belong that one can engage in a repeated encounter with no great sense of threat.

As mentioned above, the exchange may have put the teachers’ institutional authority roleunder threat, as demonstrated by his defensive posture (Baldry & Thibault, 2006), yet the expressions on observing students’ faces seem to provide the most convincing evidence that a disturbance in the classrooms’ social order has occurred, shuffling participant roles so that they no longer conform to cultural expectations. In the post-lesson interview, the teacher confirms that this classroom exchange did not conform to the expectations of the classroom culture when he says:

No I didn’t expect it from anybody here because this is the first time I got… I don’t know what happened.. she was like kind of…I think she’s the type of girl that spends lots of time reading these explanations at the end [grammar appendices] and then she was kind of like ah..ah well! I gotta explain this to the students, to my classmates.

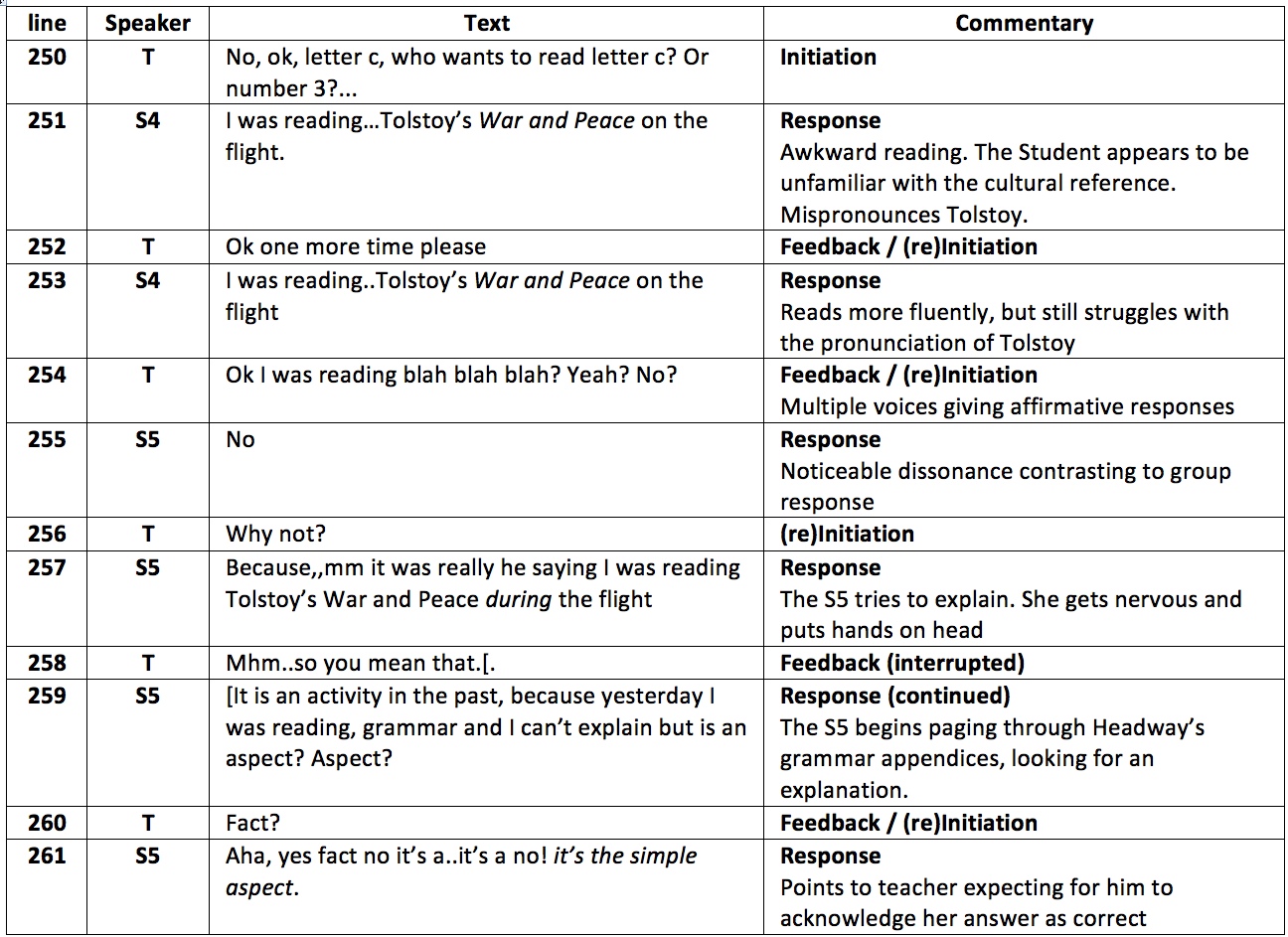

Being—doing the teacher

Below, Figure 3 continues with the depiction of the literacy event described in section 3.3 above. We see here that an unexpected response from the teacher provides unusual opportunities for the student to enact literacies that are not normally available for students within the classroom. Further discussion is provided below.

.jpg)

Figure 3: Being--doing the teacher

Table 4: Being—doing the teacher

The first image in figure 3 above depicts the teacher holding up the whiteboard marker as he says, “Do you want to come and put the example?” (see line 262 of excerpt 4). This iconic gesture co-occurs with speech (Norris, 2004) and functions pragmatically as an offer (Levinson, 1983) to take control of the whiteboard. In many ways this is a remarkable offer as the teacher is effectively relinquishing control of the lesson to a learner (albeit his to take back at any time) as well as granting access to the most salient and symbolically powerful cultural artifact in the classroom (Baldry & Thibault, 2006; Jewitt, 2008). Equally remarkable, Student 5 accepts the marker and immediately appropriates the Discourse (or literacy) and demeanor of a teacher as she begins her explanation (see image 2 in figure 3 and lines 263 above). The marker seems to function much like a scepter, endowing its user with the symbolic capital (Bourdieu, 1991) that is associated with its typical participant roles (Baldry & Thibault, 2006).

This transformation, however, cannot be accredited only to the marker in hand. During the following task, students are invited to write their answers on the whiteboard as a part of being—doing students, which provokes no change perceived classroom roles and identities (Gee, 2008). For student 5, actually employing the cultural tool (the white board marker) as its intended to be used also seems to be problematic. As Student 5 begins her explanation (see lines 263-265 of excerpt 4) she leans in to write on the whiteboard twice, placing the marker within centimeters of the surface, yet stops short both times (see image 3 of figure 3). Instead, she retreats from the prestigious semiotic zone around the whiteboard, and appeals again to the authority of the textbook sitting on her desk (see line 263 above). She holds it up in a ‘teacherly’ fashion and instructs her classmates to turn to the grammar appendices (see line 267-269). This act of directing her classmates into action seems to awaken Student 5’s sense of awareness that she has adopted a classroom role/identity that is not completely appropriate, and she laughs aloud, realizing that her literacy performance has reached excessive levels of theatrics or imitation (Kamberelis & Scott, 1992). Her laughter triggers boisterous laughter from the group, a semiotic expression which should be interpreted, in this case, as an act of solidarity rather than mockery.Student 5 confirms this interpretation in an informal interview two days after the lesson as she reports that “later my classmates congratulated me. They couldn’t believe that I could do it.”

This episode is illustrative of the symbolic power that different cultural artifacts are endowed with inside the classroom context (Baldry & Thibault, 2006). These artifacts serve as resources that offer affordances which can both enable and constrain not only meaning making practices, but the social roles and identities that are available within the classroom context. Student 5 was able to activate the meaning making potential of the whiteboard marker by using it in tandem with posture, gesture, prosody and proxemics while adopting an imitation strategy (Kamberelis & Scott, 1992) to appropriate a prototypical style of teacher Discourse (or literacy).

Discussion

The sample analyses above provide various insights into the workings of a classroom culture and the literacies that are available to be enacted by classroom participants within this sociocultural context. The classroom teacher was probably the most salient agent who afforded literacy opportunities within the classroom, as he generally allocated the floor, choose and ratified topic choices, and generally managed all classroom activity. It is important to remember, however, that the classroom culture and its history of literacy affordances both enables and constrains communication as classroom participants both cooperate with and struggle against one another in order to realize the relevant tasks at hand, which became evident in several of the literacy events examined in the analyses above.

The classroom context does offer a variety of participant roles and identities to classroom participants. The modal affordances of the classroom also play a part in determining what roles and identities are available to be enacted in the form of distinct literacies. Clear examples of different kinds of voice were appropriated by a variety of participants in the classroom, particularly by Student 5 and the teacher. The teacher, for the most part, maintained and occasionally defended his role as institutional representative and authority (Goffman, 1981), roles that he is able to employ simultaneously or shift back and forth between quite skillfully. However, he is also skilled at combining these roles with other identities/literacies such as teacher, evaluator, sympathizer, and even reconciler.

From students, we overwhelmingly saw the voiceless learner opting out (Barnes, 1976), what Kumaravadivelu (1999) describes as (possibly) being a form of “passive resistance” (p. 454). If fact, an audio narrative that was played at one point in this classroom lesson maintained the floor approximately 45 times more than the average student. There were also other forms of resistance present in the lesson. I would propose that Student 5’s overt testing/pushing of the norms and boundaries for ratified student roles and identities was a form of resistance. During an informal interview, I queried her about her motivations regarding her unusual and inspired classroom participation. She reported that she wanted to prove herself to her classmates because they could often be ‘cruel and ridiculing’ (reported in field notes). Surprised, I asked, “What about the teacher? Did you want to impress the teacher?” to which she replied, “no,” it was more for me and my classmates” (reported in field notes). Perhaps the lesson that can be learned from Student 5’s answer is that the EFL classroom provides many opportunities for inter-learner cruelty. Prabhu (1992) is insightful when claiming that learners, in a fierce, multilateral form engage in a play of personalities;

there are likes and dislikes, loyalties and rivalries, ambitions and desires to dominate, injured pride and harboured grudge, fellow and feeling jealousy, all creating a continual threat to security and self-image, and calling for protective or corrective action (p. 229).

I propose that the textbook is a particularly important resource for both teachers and students within classroom context. It played certain roles within the lesson under analyses. At times, the text can appropriate a somewhat unwilling or hapless human host, at which time, it is the text animated. Other times the text is a resource for authoritative knowledge, or the text as authority. The text can also be used as a resource for being—doing certain literacies; for example being—doing English teachers and being—doing English learners.

Finally, we might call into question the rather dogmatic, negative characterization of the IRF exchange as reviewed in section 2.3 of this article above. As Student 5 demonstrated quite effectively, the IRF exchange does not necessarily prohibit students from taking initiative, creating and negotiating meanings, asking questions or challenging the notions that are presented during the exchange. We would do well to remember, however, that it was the teacher’s rather brave willingness to temporarily relinquish control of the classroom lesson, which provided the most significant learning opportunity as well as opportunities for students to enact literacies that are rarely available within the sociocultural context of the classroom.

By examining the literacies that are available to classroom participants and the classroom conditions that provide participants with opportunities to enact these literacies, we are provided with insights as to what kinds of learning opportunities become available to students as well as how all the classroom participants are able to achieve their particular goals within the classroom context.

References

Auerbach, E. R. (1995). The politics of the ESL classroom: Issues of power in pedagogical choices. In J. W. Tollefson (Ed.), Power and inequality in language education. (pp. 9-33). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Bakhtin, M. (1981). The dialogical imagination. Austin: University of Texas Press.

Baldry, A. & Thibault, P. J. (2006). Multimodal transcription and text analysis. London: Equinox.

Barnes, D. (1976). From communication to curriculum. Penguin Books: New York.

Barton, D., Hamilton, M., & Ivanic, R. (Eds). (2000). Situated literacies and writing in context. New York: Routledge.

Bhatia, V. K. (2004). Worlds of written discourse. A genre-based view. London: Continuum.

Bourdieu, P. (1991). Language and symbolic power. Cambridge, Mass.: Harvard University Press.

Brandt, D. & Clinton, K. (2002). Limits of the local: Expanding perspectives on literacy as a social practice. Journal of Literacy Research, 34(3), 337-356.

Breen, M. (2001). The social context for language learning: A neglected situation. In C.N. Candlin & N. Mercer (Eds.), English Language Teaching in its Social Context (pp. 122-144). Routledge: New York.

Canagarajah, A. S. (1999). Resisting linguistic imperialism in English teaching. Oxford: Oxford University Press.

Fairclough, N. (1992)b. Discourse and text: Linguistic and intertextual analysis within discourse analysis. Discourse in Society 3(1) 193-218.

Freebody, P. (1991)b. Research on classroom interaction, Part II: Linguistic approaches. Australian Journal of Reading. 14 (1) 69-76.

Gee, J.P. (1998). What is literacy? In V. Zamel & R. Spack (Eds.), Negotiating academic literacies (pp. 51-59). Mahwah, New Jersey: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates, Inc.

Gee, J.P. & Green, J.L. (1998). Discourse analysis, learning and social practice: A methodological study. Review of Research in Education 23(1), 119-169.

Gee, J.P. (2008). Social linguistics and literacy: Ideology in discourses (3rd Ed.). London: Routledge.

Geertz, C. (1973). The interpretation of cultures. New York: Basic Books.

Goffman, E. (1964). The neglected situation. American Anthropologist 66(6), 133-136.

Goffman, E. (1981). Forms of talk. University of Pennsylvania Press: Philadelphia.

Goffman, E. (1997). Frame analysis. In Lemert, C. & Branaman, A. (Eds.), The Goffman reader (pp. 153-166). Oxford: Blackwell.

Green, J.L. & Weade, G. (1990). The social construction of classroom reading: Beyond method. Australian Journal of Reading. 13 (4) 326-336.

Gumperz, J. (1982). Discourse Strategies. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Hargreaves, D. (1984). Teachers’ questions: open, closed and half-open. Educational Research. 26(1), 46-52.

Jewitt, C. (2008). Multimodality and literacy in school classrooms. Review of Research in Education 32 (1), 241-267.

Kalantzis, M. & Cope, B. (2000). Changing the role of schools. In B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures (pp. 121-148). London: Routledge.

Kamberelis, G. & Scott, K. D. (1992). Other people’s voices: The coarticulation of texts and subjectivities. Linguistics and Education 4(1) 359-403.

Kress, G. (2000). Multimodality. In B. Cope & M. Kalantzis (Eds.), Multiliteracies: Literacy learning and the design of social futures (pp. 182-202). London: Routledge.

Kress, G. & van Leeuwen, T. (2006). Reading Images. The grammar of visual design (2nd Ed.). London: Routledge.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (1999). Critical classroom discourse analysis. TESOL Quarterly 33(3), 453–484.

Kumaravadivelu, B. (2008). Cultural globalization and language education. New Haven: Yale University Press.

Lemke, J. (2001). Making text talk. Theory into Practice 28(2), 136-141.

Levinson, S. C. (1983).Pragmatics. Cambridge: Cambridge University.

Luke, A. (1995). Text and discourse in education: An introduction to critical discourse analysis. Review of Research in Education 21 (1), 3-48.

Norris, S. (2004). Analyzing multimodal interaction: A methodological framework. New York: Routledge.

Prabhu, N.S. (1992). The dynamics of the language lesson. TESOL Quarterly 26(2), 225–241.

Searle, J. R. (1969). Speech Acts: An essay in the philosophy of language. Cambridge: Cambridge Univ. Press.

Street, B. (1984). Literacy in theory and practice. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Street, B. (Ed.). (1993). Cross-cultural approaches to literacy. New York: Cambridge University Press.

van Lier, L. (2001). Constraints and resources in classroom talk. In C.N. Candlin & N. Mercer (Eds.), English Language Teaching in its Social Context (pp. 90-107). Routledge: New York.

Wenger, E. (1998). Communities of practice: Learning, meaning and identity. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.