Language teaching is a complex field. Over the years, research and classroom practice have both challenged commonly held conceptions of what is effective. In fact, initial methods in English language teaching (ELT) responded to this need of finding what was best in the classroom in accordance to research. Part of this constant quest for the effective and the “research-sound” is the study on grammar teaching. Teachers and second language researchers have dedicated time to carefully explore and analyze current practices in grammar teaching. In an attempt to conceptualize grammar teaching, Ellis (2006) says that:

Grammar teaching involves any instructional technique that draws learners’ attention to some specific grammatical form in such a way that it helps them either to understand it meta-linguistically and/or process it in comprehension and/or production so that they can internalize it. (p. 84)

For many, grammar teaching is the foundation of language teaching, whereas for others, it is just an artifact, a nonessential element. However, regardless of the view one may have on grammar, it is almost an undeniable fact that its research has a special space in language research, therefore, making it an important area of concern within instructed second language acquisition. Ellis’s (2006) definition, though, comes with an underlying assumption, which is the fact that grammar teaching in general is conducive to second language (L2) learning. Positions on this topic have divided the research field for years and they will be discussed later in this study.

Grammar teaching has embodied many forms throughout the years. First, with the grammar-translation method which used a deductive teaching of grammar (Richards & Rodgers, 2016). Then, swinging the pendulum to more communication-focused approaches, as the communicative approach, grammar has always had a presence in ELT, regardless of its extent and treatment. Thus, the current study endeavors to explore and contrast the different approaches adopted by Dominican English teachers in five different contexts where English is taught as a Foreign Language (EFL). The value of this research is to have a clearer understanding of the practices used by Dominican practitioners in the teaching of grammar, and most importantly, the subtle reasons underlying their instructional decisions.

Review of Literature

Advocating for English Language Teaching in general

In order to discuss grammar teaching, the issue of the effectiveness of classroom teaching practices arises. As a result, learning a language submits to the perspectives that either agree on the positive impact of instruction or diminish its value, making teaching an oblivious business. Therefore, one question needs to be answered: Should language be taught at all? Or should we simply learn it in a native environment? Krashen (1987) suggests language is so complex that it cannot be simply acquired in the classroom; hence, he made the distinction between learning and acquisition. Many other researchers, though, do agree that the classroom experience does provide learners with comprehensible input, and exposes them to the variables required for language acquisition. Current debates on the usefulness of language teaching have resulted into a somewhat new sub-field in second language research, which is called “instructed second language acquisition” (ISLA). Loewen and Sato (2019) define ISLA as a classroom-based academic field combining scientific knowledge to gauge into what works in instructional contexts. This field in applied linguistics argues for the value of classroom teaching by explaining how explicit knowledge (e.g., information about the language and rules) can be transformed into implicit knowledge (i.e., skills retrievable at any moment). In doing so, three positions have been adopted. The first is the “noninterface position” (agreed on by Krashen & Terell, 1983), arguing for the existence and difference of the two types of knowledge, dedicating special attention to how implicit knowledge is an essential requisite for language acquisition which cannot be provided in the classroom. Second, Ellis (1993, as cited in Ellis, 2005) proposes a weak interface perspective suggesting that explicit knowledge (through classroom teaching) provides with the necessary principles that lead to acquisition. Third, there is a strong interface which believes explicit knowledge can become implicit (Loewen & Sato, 2019). Instructed Second Language Acquisition (ISLA) is based on the strong interface position and agrees on the body of research suggesting the classroom environment as a place rich of acquisitional principles which support the learner. Prabhu (1987, as cited in Richards & Ellis, 2002), for example, is one of the many authoritative voices in language research who defends classroom instruction through the use of meaning-focused tasks. Ellis (2002) corroborates this claim stating that classroom teaching, in the aspect of grammar, “does aid L2 acquisition” (p. 167).

Grammar Teaching

Once the usefulness of classroom instruction has been established, attention should be placed on the teaching of grammar as part of the language system. Celce Murcia and Larsen-Freeman (1999) describe grammar in a non-structural way, paying special attention to how its definition informs its teaching. Thus, they suggest grammar to be a system divided in three levels: subsentential level, dealing with the morphological aspects of the language; sentential levels, addressing the syntactical patterns; and lastly, suprasentential, dedicating attention to how we form discourse. Such a definition allows researchers and practitioners to see grammar in a more holistic way, and aids language education by categorizing grammar in sub-fields. Grammar teaching, on the other hand, is supported by Schmidt’s noticing hypothesis, which is believed to play an important role in learners (Nassaji & Fotos, 2004). Evidence has also shown that since learners cannot process meaning and form from input simultaneously, grammar comes as an aid in dealing with both (Skehan, 1998, Tomassello, 1998 as cited in Nassaji & Fotos, 2004). Subsequently, support to grammar teaching is also based on the lack of accuracy in meaning-based approaches. Additionally, Ellis (2006) and Long and Ortega (1983) all agree on the need for grammar teaching in the acquisition process. Another classroom-based argument for grammar is the fact that students tend to fossilize mistakes if no instruction or noticing is provided (Zhang, 2009).

Approaches to Grammar Teaching

Historically, teachers have taught grammar in many different ways over the development span of English language teaching worldwide. While addressing grammar in the classroom, a distinction needs to be made. Current treatments to grammar fall under three broad categories, namely, focus on forms, focus on form, and focus on meaning. Focus on forms is related to the teaching of grammar in an isolated, structural-like manner; deductive approaches are sometimes supported in this view. Second, focus on form allows teachers to draw students’ attention to different grammatical forms using a form-meaning nexus (Nassaji & Fotos, 2004). The latter is more pedagogically sound within the communicative approach. The same researchers agree that “such focus can be attained explicitly or implicitly, deductively or inductively, with or without prior planning, and integratively or sequentially” (Nassaji & Fotos, 2011, p. 13). Third, focus on meaning which emphasize fluent language use based on meaning, instead of forms. Meaning-focused approaches have sometimes neglected the accuracy involved in language fluency, thus, teachers adhering to such a view for grammar treatment usually fall short in fostering language accuracy in students.

Deductive & Inductive Approaches

Summarizing Widodo’s (2006) research on the matter, a deductive approach involves “rules, principles, concepts or theories,” which are presented first and then applied. One advantage of this approach is that it is instructionally time-saving, and favor learners with analytical leanings in language learning. A disadvantage, though, is how teacher-centered deductive teaching is, and how unlikely is the form to be remembered and used by students later. Contrastively, an inductive approach is concerned with subconscious learning processes, which emulate language acquisition. In this approach, learners “pick up” rules, it involves noticing, and a combination for meaning-form. An advantage in this approach is how this approach exploits learners’ critical thinking and cognition, through discovery and constant hypothesis-making; while, a disadvantage is how meticulously planned lessons should be so that learners pick up the right forms, and what they do with the input they are receiving.

In addition to these three approaches, Doughty (2003) discusses how explicit grammar teaching involves rule explanation, attention to forms, and explicit teaching. Implicit instruction, on the other hand, is more concerned to rule explanation as derived from examples. Also, students’ attention to form is not based on a formula but on actual language samples, which can clearly convey meaning to students. Additionally, research from Norris and Ortega (2000 as cited in Doughty, 2003) discusses how within the focus on form realm, 30% of teaching is implicit, while 70% is explicit. By now, it is important to summarize several things. First, grammar can be dealt with implicitly or explicitly, depending on how it is conceived in the instructional design of the class. This means that teachers could decide to include grammar in the lesson (explicit) or choose not to necessarily have grammar as part of the syllabus or instructional plan, and, instead, have it dealt with incidentally (implicit). Second, grammar teaching can be deductive, as to how it is presented within a lesson, deductive teaching generally involves formulas, or teaching can be inductive, which means students will be motivated to make out the rules on their own and focus on meaning first, and form later. Nassaji and Fotos (2004) provide a compelling overview of broader approaches to deal with grammar. These are as follows:

- Processing Instruction. Encourages initial exposure and processing activities to foster comprehension instead of production. Consciousness-Raising activities fit this criterion.

- Interactional Feedback. Emphasizes error correction, negotiation, feedback, clarification requests, and techniques alike are in charge of accuracy in the classrooms. Therefore, grammar is subsequent to sustained production and communication

- Textual Enhancement. Manipulates texts in order to expose students to notice different forms. A common strategy is input flood, in which students see the target form in numerous occasions.

- Task-Based Instruction. Uses communicative tasks, which have a focus on meaning, and can be adapted to draw learners’ attention to forms, thus, making these tasks “focused.” On the other hand, “unfocused” tasks are mainly used for communication (Ellis, 2003 as cited in Nassaji & Fotos, 2004).

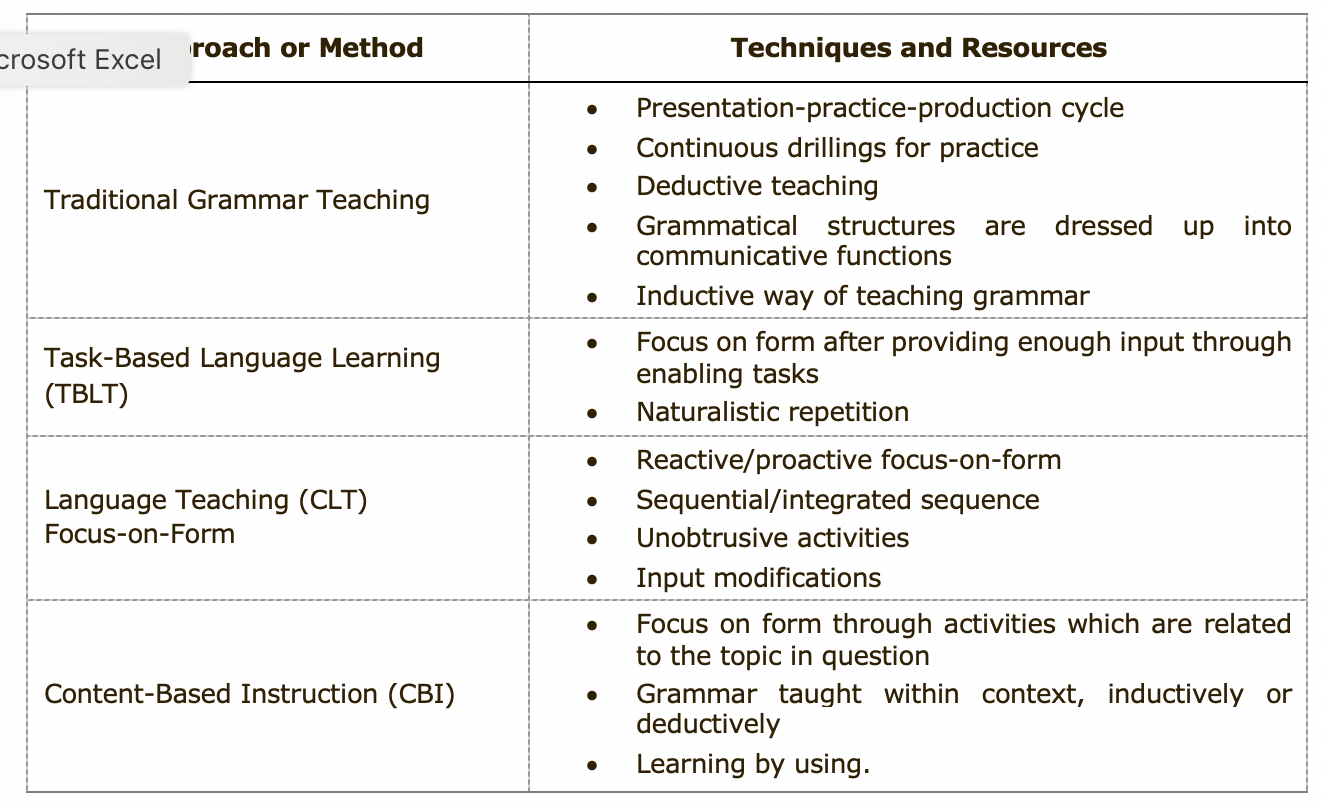

Furthermore, under the scope of the communicative approach implementation, as contrasted with traditional grammar teaching approaches, Rama and Agulló (2012) summarize what has been implemented over the last years in the ELT field. Their findings are presented in Table 1 as well.

Table 1: Current approaches to grammar teaching (Adapted from Rama & Agulló, 2012)

Teachers and Grammar Teaching

The study of grammar teaching cannot neglect what and how teachers think about grammar. In fact, as active agents in the teaching-learning process, teachers’ decisions deserve a thorough analysis since the rationale behind those ideas reveal as much as the actions themselves. Önalan (2018) reflects on such importance stating that teachers make instructional decisions, which align to their own practical theories. He goes on to say that “teacher cognition, which mainly focuses on identifying what teachers think, know and believe, is essential to understanding teachers’ cognitive framework as it relates to the instructional choices they make” (p. 1). While surveying key literature on the matter, one may assert that teachers’ complex belief system influences their decision-making and their approach choice. For instance, it is generally believed that the teacher’s personal language experience can also have an effect on the methodology chosen. Additionally, it is said that teachers who studied on a grammar-translation method, or with strict, deductive grammar teaching, are likely to replicate the same style in their own teacher. Farrell and Lim (2005) studied teachers’ cognition on grammar and argued that teachers do consider grammar teaching essential to developing accuracy in (at least) written work. Additionally, Önalan (2018) noted that “evidence suggests that how teachers handle grammar is strongly influenced by their views about language learning, their beliefs about their students’ needs and wants, and other contextual factors such as time” (Farrell & Lim, 2005 as cited in Önalan, 2018, p. 2). A study on teacher’s cognition demonstrated the following beliefs:

- Teachers should present grammar to learners before expecting them to use it;

- Learners who are aware of grammar rules can use language more effectively than those who are not;

- Repeated grammar practice allows learners to use structure fluently;

- Grammar should not be taught separately but integrate other skills. (Önalan, 2018)

Farrell and Lim (2005) extend the discussion by explaining how teacher’s enthusiasm toward new and alternative methods to grammar teaching does not translate into classroom practice due to the “emotions and attitudes attached to traditional grammar teaching and learning” (Richards, Gallo & Renandya, 2001 as cited in Farrell & Lim, 2005, p. 10). Again, complex teaching beliefs about grammar teaching and learning are the ultimate filter through, which a specific approach is adopted or preferred by a certain language teacher.

General Objective

Identify the different approaches to grammar teaching adopted by teachers in the Santo Domingo’s EFL context.

Specific Objectives

- To explore Dominican teachers’ beliefs on teaching grammar.

- To identify which grammar teaching approaches and techniques are currently applied in different types of EFL institutions within the Dominican Republic.

- To contrast how grammar teaching practices differ from one institution to another and its implications in lesson outcomes.

Methodological Framework

Type & Approach

This study is exploratory in nature and follows a mixed-method approach to second language acquisition research. Both quantitative and qualitative data were used to research teachers’ treatment to grammar. First, a survey was sent to teachers which aimed at describing teachers’ underlying beliefs about grammar teaching in general. The survey items were adapted from a previous exploratory research paper carried out by Önalan (2018). Questions were simplified in language, and asked participants to answer by using criteria spanning from Strongly Agree, Agree, Neutral, Disagree, andStrongly Disagree. A total of 55 participants from varied contexts answered this survey. The number was randomized, not sampled. No demographic variable was used to filter participants’ answers, as this data was used to validate and provide a more general vision to the grammar lesson observations carried out. Survey items are available in the appendix.

Second, a case study composed by lesson observations to 5 teachers provide with the qualitative part of this research. According to Duff (2012), a case study is far-reaching as it focuses on a “small number of research participants (...), the individual’s behaviors, performance, knowledge, and/or other perspectives ” (p. 95) Therefore, in an attempt to see the lesson implications of teachers’ beliefs, these five grammar lessons were observed. These teachers were randomized in nature; however, their contexts were different. Teachers observed were from each a public university, a private university, a public school, a private school, and a private institute. The reason behind this selection was to maximize the reach of the exploration by covering different EFL contexts in the country. In order to protect the identity of these teachers no name will be used, instead they will be classified as follows in Table 2.

Table 2: Participants in the Study

Instruments and techniques for data collection

This study gathered answers from 55 different teachers around 5 different institutions through a grammar survey which helped us identify the general knowledge English teachers have on English grammar teaching, and then compared that data with class observation data. As explained before, two instruments were mainly used: surveys and lesson observations. Survey questions are included in the Appendix.

For the grammar lessons, observers were the actual researchers. Lesson observations sought to explain grammar lessons through the following five questions:

- How did the teacher introduce grammar?

- How did the teacher explain/present grammar?

- Which were the techniques observed? (e.g., elicitation, TPS, etc.)

- How did the teacher check for understanding?

- Would you consider the grammar lesson effective? Why? Why not?

Observation-based responses to these questions are blended in the analysis of the questionnaire answers in order to provide stronger data support to the findings.

Results

Survey Results

When asked questions that favored deductive/explicit teaching, it was evidenced how 93% of the participants believe students communicate more effectively by knowing grammar rules. This is also supported by the 72% of participants who answered that students use the language more effectively when they have conscious and sufficient knowledge about grammar. Though most teachers either agreed or strongly agreed with the importance that grammar has in developing communicative competence, only 32% favored knowledge about grammar terminology. In spite of the fact that the vast majority of teachers favored deductive instruction, only 25% of teachers favored its separation from other skills.

Similarly, 54% of teachers agreed that grammar should be presented to learners before expecting them to use it. Opposite arguments were obtained when prompted about fluency in a foreign language. Forty-five percent of teachers (44%) of teachers agree that grammar is necessary in order to speak a foreign language fluently while 38% disagreed. Lastly, 71% of the teachers were in favor of controlled grammar exercises. They argued that this type of exercise accounts for fluency. On the opposite side, when teachers were asked items that infer inductive teaching, their answers vary to those from the deductive teaching items. First, although teachers favored deductive teaching and presentation of rules prior to use, 71% of teachers favored students’ own discovery of grammar in context. In addition, 56% agreed that a focus on form should come after communicative tasks, while 41% either disagreed or were neutral. Lastly, 53% of the teachers disagreed with the idea that communicative tasks without a focus on form should be used in classrooms.

Teachers were also asked about techniques they use to assess learning. The results evidenced how traditional language teaching still takes place in classrooms. Eighty-five percent (85%) of the teachers surveyed answered that they have their students create sentences and complete exercises in the coursebook after grammar is presented. Similarly, it was also shown that 81% of the teachers use fill-in-the-blank and information gap exercises (as cloze texts) to assess learning. Contrastively, 78% of teachers stated they favor communicative tasks, but only 55% favor pair work. Even though teachers previously showed their disagreement with grammar separation from other skills, only a 49% of teachers integrate it with other skills as listening. Surprisingly, only 1 participant, accounting for 1.8% of the surveyed participants, favored role plays as assessment. Regarding lesson sequence, the predominant result is that teachers first present the grammar, then the grammar is practiced with the students, and teachers have students use it in context.

Observation Results

An amount of 5 different institutions were considered for this study. In order to understand and draw conclusions from the observations, patterns were observed.

Table 3: Observation results

Discussion

The study evidenced how predominantly teaching practices still take place in different institutions in Santo Domingo. Most of the participants favored deductive grammar teaching which provides supportive evidence to the results from a similar study carried out by a Language Institute in Texas (see Önalan, 2018) in that non-native -speaker teachers showed a tendency for deductive teaching. The observations showed that although teachers answered that they favored communicative tasks in grammar teaching, a lack of a production or fluent language stage use within their instructional design was evident in their teaching. This could be due to a lack of principles and informed teaching practice. It was also observed how teachers from different institutions show a tendency for teacher-centered classroom in which teacher-student interaction takes place most of the times. For controlled practice, it was evident how most teachers resorted to the use of worksheets and coursebook exercises for controlled practice. Teachers should consider a shift from coursebook and worksheet exercises to communicative tasks.

One significant result that emerged from the study is that only a handful of teachers agree that grammar terminology accounts for learning. However, it is evident how teachers from different context almost always use grammar terminology when presenting grammar. Teachers also seem to implement a straightforward approach to grammar presentation, being the use of the grammar the ultimate goal. This provides contradictory evidence to the results of the observation, in which a lack of production/fluent use stage was evident. Teachers seem to be aware of the goal of language learning but fail to implement communicative tasks in their teaching and only apply controlled grammar exercises.

Participant teachers from the study seem to consider grammar as a systematic process. Teachers’ approaches to grammar teaching do not seem to vary much from institution to institution. However, one pattern that was observed was the use of L1 in public institutions – as observed in the public school – and private university. One consideration that must be taken into account, however, is that teachers who commonly make informed instructional choices in the observations have a professional background, meaning formal studies in the field. Other teachers who may not have a strong educational background show beliefs and principles of lesson stages but at times fail to implement them in classrooms. Though deductive instruction is the predominant and only approach observed, inductive techniques were present in some of the classrooms. Whereas survey results show a tendency for pair work and group work, teacher-student interaction is what was mostly observed when scaffolding concepts and practicing grammar. Teachers mostly resort to worksheets and book exercises to check for understanding, and teacher-student elicitation follows them. In terms of communicative skills development, most lessons observed did not seem to account for it. Though few exceptions were observed, these happened because of the teachers’ educational background and informed teaching choices.

Conclusion

The results presented in this research paper suggests that grammar teaching is still a matter of discussion when being addressed by teachers, and that even though most of the practitioners in the study see it as an important part of language teaching, it is not treated consistently properly. Since grammar instruction is viewed as a complex process, many teachers find it difficult to engage students in the class when it comes to presenting a grammar point, as well as to motivate them to construct meaningful information based on previous instruction. Additionally, many of the grammar teaching approaches adopted do not necessarily align with innovative, research-based updates within applied linguistics and second language research. Therefore, teachers find themselves prompted to take the easy road and not to apply effective approaches and techniques that may help their grammar instruction be functional, which results in not obtaining the desired outcomes from students.

Moreover, the majority of the teaching centers observed are not providing the training teachers need in order to improve their grammar instruction specifically. This paper indicates that principals and coordinators from the different teaching centers in this research have not raised awareness among their teachers regarding grammar instruction; that is one of the reasons why the outcomes, as presented in the findings of this study, are not felt to be satisfactory and it suggests action needs to be taken to lower the lack of accuracy in grammar teaching.

Lastly, although there are limitations to the outcomes of the study, the results obtained are representative of how grammar is taught in the Dominican Republic in its different situational contexts.

Recommendations

In the light of the findings presented in this study and our reflections on these, the authors suggest the following steps in order to raise the quality of grammar instruction in our EFL context:

- Further professional development opportunities in order to raise awareness of the importance of developing communicative competence in grammar teaching, and the importance of having the students use the language they are to acquire;

- Instructional coaching and feedback are necessary in order to improve grammar teaching in the centers observed;

- Raise awareness of the different approaches to grammar teaching within the communicative approach.

- Periodical team meetings should be scheduled to discuss what is working or not regarding grammar instruction, as well as to analyze students Ì responses towards grammar teaching;

- Assessment of textbooks and teaching techniques in order to evaluate their effectiveness;

- Training on the use and creation of instructional materials and communicative tasks in the classroom, in an attempt to replace direct use of worksheets and textbook exercises;

- Exposure to research-based practices in grammar teaching and involvement in classroom action research as a way to awaken inquiry of learning results in the classroom; and

- Professional Learning Networks (PLN) as a means for sharing best practices in grammar teaching and critically evaluate teachers’ beliefs on grammar and its teaching in the classroom.

References

Celce-Murcia, M., & Larsen-Freeman, D. (1999). The grammar book: An ESL/EFL teaching course. Boston: MA: Heinle & Heinle.

Doughty, C. (2003). Instructed SLA: Constraints, compensation, and enhancement. In M. Long, & C. Doughty (Eds.). The handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 256-310). Malden, MA: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Duff, P. A. (2012). How to carry out case study research. In S. M. Gass & A. Mackey (Eds.). Research methods in second language acquisition: A practical guide (pp. 99-116). West Sussex, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Ellis, R. (2002). Methodological options in grammar teaching materials. In E. Hinkel & S. Fotos (Eds.), New perspectives on grammar teaching in second language classroom (pp. 155-179). Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

Ellis, R. (2006). Current Issues in the Teaching of Grammar: An SLA Perspective. TESOL Quarterly, 40(1) 83-107. https://www.jstor.org/stable/40264512

Farrell, T. S., & Particia, L. P. (2005). Conceptions of grammar teaching: A case study of Teachers' Beliefs and Classroom Practices. Teaching English as a Second or Foreign Language, 9(2), 1-13. http://www.tesl-ej.org/pdf/ej34/a9.pdf

Loewen, S., & Sato M. (2019). Instructed second language acquisition and English language teaching: Theory, research, and pedagogy. In X. Gao (Ed.) Second handbook of English language teaching (pp. 1-19). Switzerland, CH: Springer.

Nassaji, H., & Fotos, S. (2004). Current developments in research on the teaching of grammar. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 24, 126-145. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0267190504000066

Nassaji, H., & Fotos, S. (2011). Teaching grammar in second language classrooms: Integrating form-focused instruction in communicative context. New York, NY: Routledge.

Önalan, O. (2018). Non-native English teachers’ beliefs on grammar instruction. English Language Teaching, 11(5), 1-13. 10.5539/elt.v11n5p1

Rama, J. L., Agulló, G. L. (2012). The role of grammar teaching: from communicative approaches to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages. Revista de Lingüística y Lenguas Aplicadas, 7, 179-191. http://dx.doi.org/10.4995/rlyla.2012.1134

Richards, J. C., & Rodgers, T. S. (2016). Approaches and methods in language teaching. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Richards, J. C., & Renandya, W. (Eds.). (2002). Methodology in language teaching: An anthology of current practice. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press.

Widodo, P. H. (2006). Approaches and procedures for teaching grammar. English Teaching: Practice and Critique, 5(1), 122-141. http://citeseerx.ist.psu.edu/viewdoc/download?doi=10.1.1.615.3645&rep=rep1&type=pdf

Zhang, J. (2009). Necessity of grammar teaching. International Education Studies, 2(2), 184-187. https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/EJ1065690.pdf