Introduction

Large scale mobility and globalization have led to increased contacts between speakers of different languages and representatives of different cultures. As a result, educators must prepare their students for successful functioning in the contemporary world. Besides, the internationalization of education has become a way of preparing students for the challenges of a globalized world. In consequence, internationalizing the curriculum in higher education has received increased attention in recent years (Leask, 2015) and preparing students through an international curriculum provides a means to develop global awareness (Burnouf, 2004; Zhao, 2010). In other words, one of the objectives of higher education is to teach students about the complexity of global problems and to help them appreciate “the value and viability of worldviews different from their own” (Schultheis-Moore & Simon, 2015, p. 2), or to question “previous unchallenged assumptions and prejudices” (Walker, 2006, p. 47). Furthermore, it is essential that students have experiences that prepare them to thrive in a diverse world. This practice is needed to be successful in both college and the workforce in the age of global competition and collaboration (Wagner, 2014).

One way of preparing students for the contemporary challenges is to equip them with a set of skills to facilitate successful communication. Building effective communication skills in a globalized world requires not only language proficiency, but also intercultural competence (Dooly & O’Dowd, 2012). The latter is especially critical for foreign language learners “who might not be fully aware of how their intended intercultural meaning is going to be ‘read’” (Orsini-Jones, Conde, & Altamimi, 2017, p. 208). A new objective for language teachers is thus to help learners develop into “informed and engaged global citizens” (Godwin-Jones, 2015, p. 18) who are aware of their own culture and can critically examine similarities and differences when conversing with representatives of other cultures.

Virtual exchanges[5] provide a convenient platform for developing abovementioned linguistic and intercultural competences as they facilitate linguistic and cross-cultural contacts by utilizing Internet technologies (Helm & Guth, 2010; O’Dowd, 2018). Furthermore, several studies on virtual exchanges show how skills for global citizenship can be developed in these settings (Orsini-Jones et al., 2017; Orsini-Jones & Lee, 2018) and suggest that engaging students from globally diverse contexts in virtual exchanges may also lead to increased global awareness (Chun, 2015).

Both globalization and the widespread use ofEnglish as a global lingua franca have been exerting a tremendous impact on language learners’ identity construction. Ushioda (2011) claims that participation in the global community is important for English language learners nowadays, and what highly motivates them, is “self-representations as de facto members of these global communities” (p. 201), rather than identiï¬cation with traditional reference groups of speakers of the target language. Henry and Goddard (2015) pinpoint the role of globalization and English as a global lingua franca as a cause for hybrid identity construction. In their study, students enrolled in an English-medium program seemed to demonstrate a hybrid identity rather than bicultural identities due to immersion in the international learning environment. Furthermore, Kohn and Hoffstaedter (2017) point to a liberating effect of using pedagogical lingua franca in virtual exchanges on non-native speaker identity, demonstrated by increased satisfaction and self-confidence in the ability to communicate effectively among the non-native speaker participants.

Drawing on the potential of lingua franca communities and computer mediated communication on identity emergence (Block, 2009), this study seeks to explore how virtual exchanges can contribute to global awareness development and, consequently, if the increased global awareness can lead to emergence of facets of global identity among participants, such as better understanding of being a part of global community and developing responsibility to act.

Review of literature

Defining global awareness and global (citizenship) identity

Although the definitions of global awareness vary among authors, knowledge concerning both the world’s affairs and the interdependence between people seem to be the core elements of these definitions. For example, Hanvey (1976) uses the term global awareness and cites five dimensions that students need to learn about as they become more globally aware. Those five categories are: perspective consciousness, state-of-the-planet awareness, cross-cultural awareness, knowledge of global dynamics and awareness of human choices. The cross-cultural awareness dimension includes recognition that ideas and practices differ among societies. Next, Case (1993) describes global awareness as universal values and cultural practices, global interconnections (economic, political, ecological, technological), worldwide concerns and conditions, past patterns of worldwide affairs and future directions of worldwide affairs. In addition, people should be open-minded and resistant to stereotyping anticipation of complexity, empathy and non-chauvinism. Further, according to Kirkwood (2001), globally aware individuals are equipped with digital skills and are knowledgeable about the affairs of the contemporary world. They easily adapt to new surroundings and manifest a high degree of willingness to act. Finally, Byram’s (2009) notion of critical cultural awareness is related to global awareness by promoting the individual's engagement with people of other ideologies, seeking areas of agreement where necessary, but also embracing difference.

In their model of global citizenship, Reysen and Katzarska-Miller (2013), define global awareness as “knowledge of global issues and one’s interconnectedness with others” (p. 861). Moreover, global awareness is identified as an antecedent of a more complex construct that is global citizenship identity. In other words, the authors claim that both the individual’s global awareness and the endorsement of global citizenship given by people in one’s immediate surrounding environment are likely to predict the individual’s future identification with global citizens. Therefore, knowledge about the world’s affairs and one’s interrelatedness with others paves the way to identification with global community.

Scholars agree that the concept of identity is “multiple, changing, overlapping, and contextual, rather than fixed and static” (Banks, 2017, p. 5), consequently, clarifying the constructs of global citizenship identity, intercultural citizenship and global identity is difficult because of a multitude of definitions provided by scholars from several disciplines. While some authors use the terms correspondingly, others distinguish their different meanings (Mansoory, 2012; Reysen & Katzarska-Miller, 2013). For example, Byram’s (2009) notion of intercultural citizenship emphasizes competences, not identities and it adds a new dimension to language education by integrating it with political education in order to respond to internationalization. In this study, the concept of global identity will be regarded as a superordinate to global citizenship identity (Reysen & Katzarska-Miller, 2013).

Global identity

Global identity has been defined in different ways and has been a segment of larger studies. Erikson’s (1967) work on identity used the label universal identity to ensure that the adolescents he worked with include global concepts in their lives and to emphasize humanism as a fundamental component in the identification of global contexts. Global identity is outlined by Karlberg (2008) as individuals moving away from competition and committing to the interest of the collective especially when making decisions. Once people have an established a sense of global identity, they may then act as global citizens realizing the impact of their actions beyond the local environment. Global identity has been explored in environmental sustainability (Cornelius & Robinson, 2011), adolescence (Goossens, 2001; Mansoory, 2012), technology readiness (Westjohn, Arnold, Magnusson, Zdravkovic, & Zhou, 2009), and virtual teams in management (Erez et al., 2013), but it is under-explored in education. Researchers recognize that education can be a venue for promoting global identity in students and it is, therefore, a venue in need of exploration. In addition, previous studies, such as the ones in environmental sustainability, call for a relationship to be established between global identity and other fields (Cornelius & Robinson, 2011).

Mansoory (2012) examined how adults defined their identity and if their established global identity led them to take action. The dichotomy of “us” versus “them” in the way people identify themselves drove the inquiry of the study. Participants were interviewed to categorize their global identity including how they feel they belong with other people. Thematic analysis revealed twenty-two themes related to global identity. The first topic, which is the most relevant for the present study, was “global identity” defined as the division in a person’s identity when they are focused on themselves versus situating themselves with others. Within that topic there were two themes: 1. Global belongingness (I am part of the world) and 2. Significance in relation to humanity (Me and the world). Although there is a continuum of where a person can fall when expressing their identity and their global outlook, the separation starts with a personal “I” being important in the world versus “we” when someone describes themselves among others. Based on these results, the author defined global identity as “... a sense of belonging to the entire human race. Identical to global identity, global belongingness was an important aspect of world citizenship, illustrating a possibly close relationship between the concepts” (p. 18). The study concluded that humans have the capacity for developing their global identity and this is facilitated through education and socialization.

In order to focus people on environmental issues such as climate change Cornelius and Robinson (2011) used global identity to see if it correlated with participants’ efforts to reduce greenhouse gasses. One hundred fifty-two high school students completed a Likert-scale survey and then completed it again after seven weeks. The survey asked them about how they were related to the world and how their behaviors related to attitudes and actions on climate change. The authors concluded that global identity was positively associated with actions such as turning off devices to save electricity and to reduce the use of cans and bottles. The authors felt this was important as environmental sustainability behaviors in young people can be strengthened with more local and global identity. They suggested that it was beneficial to promote increased global identity as a way to support activities that focus on the environment. Similarly, when studying global identity as related to technology, Westjohn et al. (2009) have explored self-service technologies. These technologies are those that allow consumers to get services without the need for human interaction such as paying and getting a movie ticket at a touch screen kiosk. Participants from both the U.S.A. and China collaborated in testing technology use in two different cultural contexts. Four hundred eighty-six people were given a survey to measure such constructs as cosmopolitanism, global identity, technology use and technology readiness. The results showed that global identity was related to technology use in that those who utilized self-service technologies and had a propensity towards globalization. Because of the close ties between language and identity (Mu, 2015) these studies showed that growth in global identity results in important considerations for the foreign language education so that students see themselves as members of the global community.

Results from Erez et al.’s (2013) study showed that team trust was important in the virtual exchange and supported global identity. Experience working in multicultural teams was cited by the authors as an opportunity to enhance global identity. Data in this study was gathered from 1,221 MBA graduate students from seventeen universities over four years. The participants were surveyed in part to measure their global identity in a project they did in class over a four-week period. The aim of the project was to have a virtual exchange in a global management course. Students had an international work experience as they collaborated on a project that was graded as one and counted as the final project for their respective class grade. Individual Likert-scale surveys to measure constructs such as cultural intelligences, local identity, team trust and global identity were given to the students.

In sum, several studies have contributed to the definition of global identity and development of global identity in people and is an important consideration especially in education. Previous studies have shown that when students become more globally aware, they have a stronger connection to the world and articulate the value of interacting with other people. Education is a setting for virtual exchanges focused on tasks that promote global awareness and can lead to global identity for students. In the past virtual exchange between different groups of students in foreign language classes have not been studied. To this end, the present study is framed in global identity because virtual exchanges are used as a platform to develop global belongingness as students are pushed to incorporate global ideas and their connections to the world since they continue to develop their identity. The ultimate goal is, through language education, to have participants incorporate a global perspective as a part of their identity.

Developing global awareness in virtual exchanges

Recent literature has highlighted participants’ global awareness development in virtual exchanges within education and teacher education. Through many configurations, researchers have underscored the value of these exchanges in the curriculum. For example, Thirunarayana and Coccaro-Pons (2016) researched teachers in a graduate program and their K-12 students as the teachers communicated with teachers in other countries. This study involved only the teachers as participants; however, it was part of a larger unique project that included teachers and their students with the goal of increasing global awareness for both groups. The teachers in the study sought out international classrooms where teachers around the world were interested in exchanges for their students as part of their course work in an instructional technology course. Journal entries of seventeen teachers were analyzed and coded into seven categories by two researchers. The study found that both the teachers and their students learned from this telecollaborative project. K-12 students broadly learned that their peers in other countries may have less resources than they do which led them to a better understanding of social and economic issues in a different culture. The teachers learned about implementing technology, specifically a virtual exchange and these types of exchanges and their benefits and drawbacks. Being virtually connected allowed for the exchange of ideas quickly and supported the exchange of first-hand information between students in different countries.

In a similar vein, Wang, McPherson, Hsu and Tsuei (2008) aimed to develop teacher global awareness through an exchange between the United States and Taiwan during graduate level teacher education programs. These teachers had the goal of including global awareness in their K-12 curriculum. Open-ended questionnaires and analysis of the dialogue between teachers along with the survey data were used. Twelve participants form the US and eight from Taiwan participated in the study. Also, the instructors of the courses were interviewed. T-test analysis showed significant attitude changes in the pre- and post-survey when the teachers collaborated with one another. The authors were able to demonstrate how exchanges via technology can promote cultural understanding as teachers share ideas. Five themes emerged from the qualitative data. The teachers were able to articulate the similarities and differences with their partners, they considered the idea of working with their partners in the future, they shared the importance of global learning to education, they shared their perceptions of using blogs, wiki and emails for their project, and they noted the language differences were a barrier to successful communication for the project. The teachers’ understanding of globalization, which includes the knowledge to be able to use it in their own classrooms, improved. The teachers noted, however, that they did need more technological skills in order to feel comfortable using technology as a way to support cross cultural projects in their curriculum. Their knowledge of blog and wiki use did increase as a result of participation in the course activities. Some of the teachers reported that they did subsequently implement activities to engage their students in global collaboration.

Furthermore, in Maguth’s (2014) study on raising global awareness in teacher candidates, twenty-six pre-service teacher candidates in a social studies methods course were partnered with a secondary social studies class of twenty-four students in Thailand. A global learning project was set up for the teachers to develop lessons on the topic of American imperialism with the Thai students. The teacher in Thailand chose a lesson and delivered it to her students and the recording of that lesson was reviewed by the pre-service teachers. Then, the pre-service teachers and the Thai students had a video conference to discuss their experiences. In the end, the pre-service teachers gave positive reviews to this authentic teaching opportunity which allowed them to consider global learning in their future curriculum development.

Furthermore, Grant (2006) demonstrated that engaging elementary-age students into an online cross-cultural project resulted in their increased global awareness. One hundred twenty-six students from elementary schools in the U.S.A., Mexico and Turkey took part in the project. Results demonstrated that the participants had overly positive perceptions of the projects and liked learning about global matters from their peers. The qualitative analysis revealed that they developed global awareness and that degree of global awareness was related to changes in participants’ social comfort zones.

There has also been some interest in exploring how intercultural virtual exchanges contribute to intercultural and global learning. Zong (2009) investigated the development of teacher candidates’ understanding of global education as a result of their participation in a computer-mediated multicultural communication project. Project reports submitted by fifty-nine pre-service teachers who communicated with students and teachers from twenty-six countries all over the world for the period of three semesters were analyzed qualitatively. The results suggested that the participants appreciated authentic online communication with peers from various countries. Evidence of empathy and willingness “to act to make positive changes” (Zong, 2009, p. 621) was reported. Further, the analysis showed that the participants’ understanding of global education developed in six categories. They found global education to be the means to learn about cultural diversity, tolerance, important global issues and challenges, cooperation between countries.

Overall, the findings of the studies utilizing online intercultural exchanges suggest that these types of projects are conducive to development of global awareness and the participants largely appreciate the opportunities to learn about the world from their peers living in other countries.

Research questions

Although research on virtual exchanges has shown to provide opportunities for global awareness development, there is a scarcity of studies that explore the development of global identity in the field of foreign language education. Nonetheless, education can be a platform to promote global identity. For these reasons, this study focuses on virtual exchanges in the language learning classroom with the goal of global identity development and answers the following research question: In what ways do virtual exchanges help develop global awareness, more specifically as an antecedent of global identity, among foreign language learners?

Methodology

Data collection instruments

The present study used both quantitative and qualitative data. In addition to a pre-survey, participants also completed a post-survey after the virtual exchange. Statistical analyses were conducted on responses to Likert-scale items utilizing SPSS, while data from open-ended responses and final group projects was coded using NVivo. The purpose of utilizing both types of data was to gain better understanding of the development of the research problem (Sandelowski, 2003).

Likert-scale type questions with seven levels (1 strongly disagree; 7 strongly agree) were used on surveys. In these questions, participants self-rated their agreement to a particular statement regarding global awareness using Reysen and Katzarska-Miller’s (2013) survey. It was adapted by the researchers in two ways. First, by asking only the questions related to the participants’ ratings of global awareness. Second, in the study by Reysen and Katzarska-Miller (2013) the survey was distributed only once, but the participants of this study completed the same survey before and after the virtual exchanges. As per Reysen and Katzarska-Miller (2013), four items (i.e., “I understand how the various cultures of this world interact socially,” “I am aware that my actions in my local environment may affect people in other countries,” “I try to stay informed of current issues that impact international relations,” “I believe that I am connected to people in other countries, and my actions can affect them”) were combined to form a global awareness variable. Participants also answered one open-ended question, “What is global awareness?” on both the pre- and post-surveys.

Participants

There was a total of eighty-four foreign language learners (n = 84) that made up forty-seven groups during the virtual exchange. These 2-3 people groups were formed based on participants’ availability out of class. Participants were registered undergraduate and graduate students in one of seven second language (L2) courses at one of four universities that participated in the virtual exchange project (two in the United States, one in Mexico, and one in Poland). The virtual exchange was a required component of all of these L2 courses and all students participated in exchange activities. However, only 84 students consented to having researchers use their coursework for data analysis. Therefore, researchers utilized convenience sampling (Gall, Gall, & Borg, 2003).

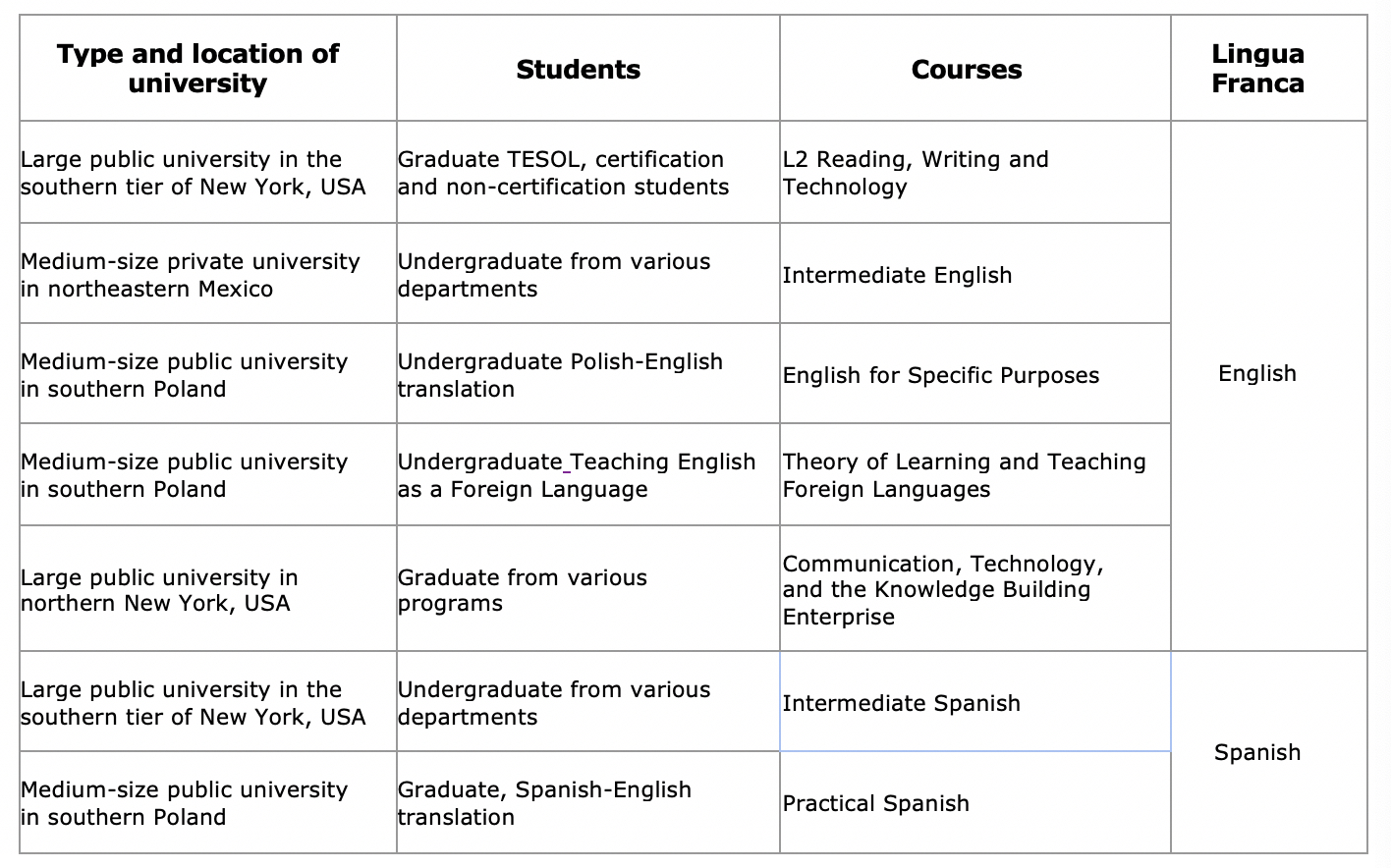

All participants were partnered with at least one international partner from one other university and were instructed to synchronously meet, via Zoom, with partner(s) for six weeks and to communicate in English or Spanish as the pedagogical lingua franca. This virtual exchange was a required part of participants’ coursework (Erez et al., 2013) and was clearly stated in each course’s objectives. The average age of participants was 23.3 years old (SD = 5.9). Table 1 summarizes partnering institutions, courses, and languages used for virtual communication.

Table 1. Partnering institutions and course details

Data Collection

Data for the study were collected at the beginning and at the end of the project when participants completed a pre-survey prior and post-survey after the exchanges. For six weeks, the participants met with their partner(s) via Zoom videoconferencing (https://zoom.us) (Bohinski & Mulé[6], 2016; Lenkaitis, 2019; Lenkaitis, Calo, & Venegas Escobar, 2019), to synchronously discuss weekly topics as it has shown to facilitate participation in group work (Lenkaitis & English, 2017). They met for at least a 15-minute session and used a pedagogical lingua franca (English or Spanish) in order to share ideas regarding the weekly topics using a common language.

For the four weeks following introductions in Week 1, groups met to discuss weekly topics and current event photos, piloted and chosen by authors, in order to promote interaction in task-based L2 learning (González-Lloret, 2003). Weekly topics included sports and patriotism (Week 2), advertising (Week 3), crime (Week 4), and natural disasters (Week 5). Finally, in Week 6, group members synchronously met to work together in constructing a final project. There were no explicit instructions related to global awareness as authors wanted to see what development occurred as a result of unstructured synchronous meetings. Nonetheless, participants were asked to record their Zoom sessions and upload them to a shared Google folder so that they could be reviewed.

Results

Overall, after reviewing the recorded synchronous sessions uploaded by participants, the study’s participants met, via Zoom, for 273 individual sessions totaling over 118 hours over the course of the 6-week virtual exchange. Each of the 84 participants synchronously communicated with their partner(s) for over eight hours over the course of the 6-week virtual exchange.

Quantitative analyses

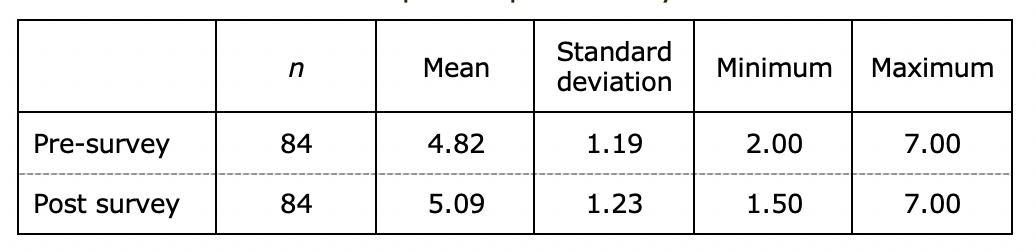

Statistical analyses were complete on the pre- and post-survey Likert-scale questions using IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0. The 4-question pre-survey (4 items; α = 0.80) and post-survey (4 items; α = 0.88) that were used was found to be very reliable. These results show a high level of internal consistency and satisfy the generally accepted reliability threshold of about 0.70 (Nunnally & Bernstein, 1994). A nonparametric Wilcoxon sign-rank test was used to analyze the ordinal data obtained from the pre- and post-survey Likert-scale questions using IBM SPSS Statistics 25.0. The test was run to find out if global awareness among students changed after their participation in the virtual exchanges. Table 2 provides descriptive data on the comparison of participants' ratings of global awareness before and after the virtual exchanges. As seen in Table 2, the mean values increased from the pre- to post-survey.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics in global awareness ratings.

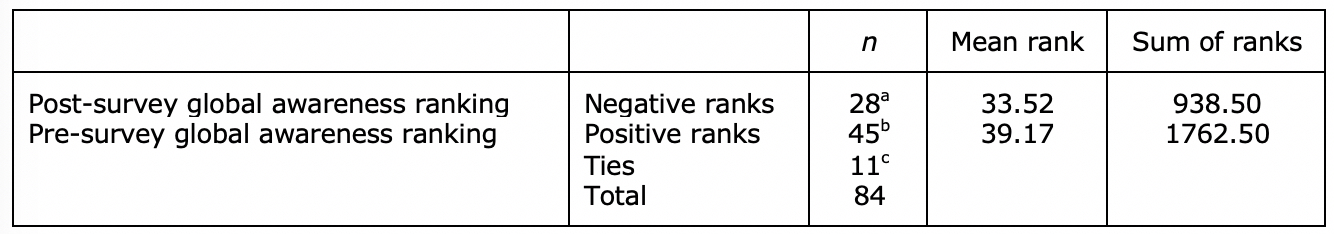

Table 3 provides data on the comparison of participants' ratings of global awareness obtained from the pre- and post-survey. Forty-five participants ranked global awareness higher in the post-survey than before their experience of virtual exchanges. However, twenty-eight participants ranked global awareness higher before the project and eleven participants saw no change in their ratings of global awareness.

aPost-survey -global awareness ranking < Pre-survey - global awareness ranking

bPost-survey -global awareness ranking > Pre-survey - global awareness ranking

cPost-survey -global awareness ranking = Pre-survey - global awareness ranking

Table 3. Ranks

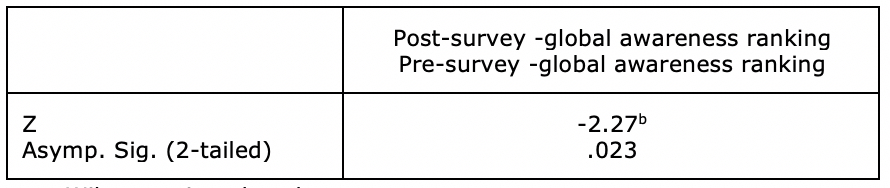

As seen in the Test Statistics Table 4, the difference in the ratings of global awareness obtained in the pre- and post-surveys is statistically significant (Z = -2.272, p = 0.023).

aWilcoxon signed-ranks test

bBased on negative ranks

Table 4. Test statisticsa

To conclude, the Wilcoxon signed-rank test showed that a 6-week virtual exchange project did elicit a statistically significant change in global awareness ranking among the participants (Z = -2.27, p = .023).

Qualitative analyses

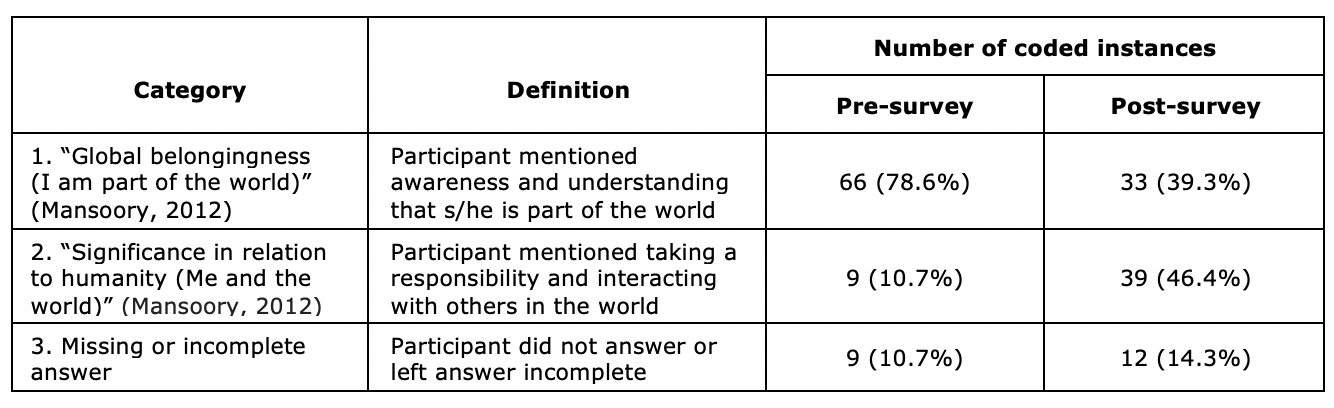

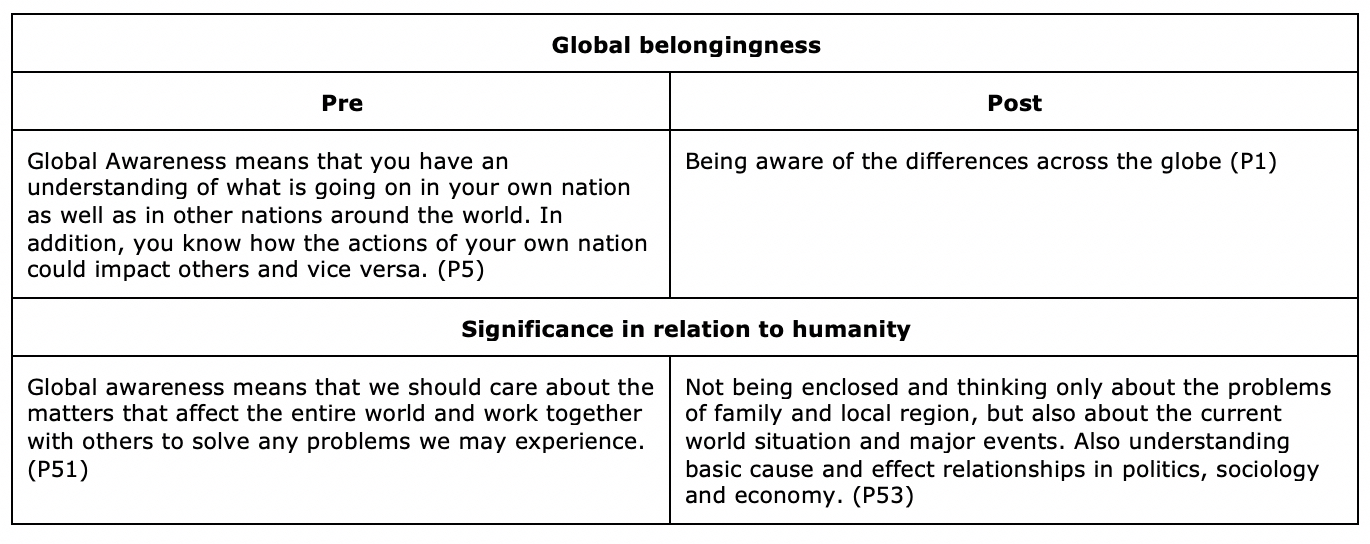

The open-ended responses on the pre- and post-surveys to the question: What is global awareness? were coded using NVivo 12 for Windows. In order to analyze these answers for the emergence of global identity, the answers were coded into one of the three categories, two of which were categories from Mansoory (2012), the third category included missing or incomplete answers. The Global belongingness and Significance in relation to humanity categories were chosen as they were the only ones indicated as subcategories under global identity in Mansoory (2012). Two researchers coded the data independently. A 90.7% agreement was achieved (Kappa = .55 with p < 0.001), but the researchers worked together to reconcile any differences. Table 5 lists the three coding categories, their definition and the coding breakdown for the pre- and post-surveys while Table 6 lists examples of coded open-ended survey responses. Specific participant examples are abbreviated P for participant.

Table 5. Coding categories and pre- and post-survey breakdown

Table 6. Examples of open-ended survey responses

Coding shows that before the virtual exchanges, sixty-six of the eighty-four participants indicated a sense of Global belongingness while in the post-survey there was thirty-three participants. Because of this decrease in Global belongingness, there was an increase in the identification with Significance in relation to humanity from the pre- to post-survey. When looking at individual participants, thirty-two out of eighty-four participants (38%) identified with Global belongingness in the pre-survey but in the post-survey identified with a Significance in relation to humanity in the post-survey. Fifty-one percent of all participants identified with the same global identity category in both the pre- and post-survey.

Analysis and discussion

The impact of virtual exchanges on global awareness development among foreign language learners

Drawing on the results of the pre- and post-survey, it can be concluded that the virtual exchanges conducted by the participants made a significant impact on their development of global awareness among participants. Two inherent elements of virtual exchanges have contributed to this finding. First, because of direct contact with peers living in geographically remote countries, the participants had a chance to learn new information related to the weekly topics from the perspective of their partner(s) culture through the pedagogical lingua franca. The first-hand accounts of the events and problems typical to their partner’s culture made the participants feel more knowledgeable about the world, therefore their self-reported level of global awareness increased significantly. Although they knew “that there are differences in culture,” participants realized that they “can bridge those differences” by “find[ing] common ground” (Participant 27).

Participants became “informed about what's happening in the world” (Participant 26) and understood “the cultural, societal, economic, political, etc. variations between peoples and regions, and how they are constantly changing.” (Participant 31). This explanation resonates with the findings reported by Thirunarayana and Coccaro-Pons (2016) who demonstrated that participation in the virtual exchanges made teachers and learners more aware of issues pertaining to education in other parts of the world. Secondly, by being engaged in collaboration with foreign peers, the participants were able to better recognize their affinity with humans who live in other parts of the globe, as cooperative learning in general promotes “interconnectedness with others” (Reysen & Katzarska-Miller, 2013, p. 868). As Participant 23 stated “That we, people, are aware of others living in this world and that we respect each others [sic].” In the telecollaborative settings, the positive impact of virtual exchanges on the change of participants’ attitudes was also demonstrated by Wang et al. (2008).

Virtual exchanges and development of global identity

It is evident that the virtual exchanges provided students with the opportunity to develop their global identity. After the exchanges, participants felt a greater responsibility to humanity (Mansoory, 2012). In post-surveys, participants realized that there was a connection between them and the world and saw themselves as part of it. They no longer had an “I” mentality but a “we” one as can be exemplified by Participant 5’s open-ended response that “We need to collaborate, and learn from other cultures. In addition, we need to support them when appropriate.” Although participants expressed that there were differences between them and other parts of the world, these differences did not stop them from changing their mentality to include other parts of the world. Because participants established a sense of global identity, they realized that their actions had an impact beyond the local environment (Cornelius & Robinson, 2011) and had “a recognition and appreciation of the size, complexity, and diversity of the earth” (Participant 59).

This study shows that increased global awareness can lead to emergence of global identity among foreign language learners. By discussing the assigned topics with their partners from another part of the globe, the participants became more knowledgeable about the cross-cultural perspectives on these topics. When asked to define global awareness, developments in the students’ perceptions before and after the exchanges were identified. Before the exchanges, a majority of the foreign language learners (78.6%) demonstrated understanding that s/he is part of the world and after the exchanges, only a few foreign language learners (10.7%) mentioned taking a responsibility and interacting with others in the world. After the project, these proportions changed. Only 39.3% of participants expressed awareness and understanding of being part of the world. Almost a half of participants (46.4%) manifested a felt responsibility and a need to interact with others which has been coded as “significance in relation to humanity (Me and the world)” (Mansoory, 2012, p. 16). Although not all participants showed this connection to the global community, they still exhibited the emergence of global identity as seen by their open-ended responses. In this way, this study suggested that virtual exchanges could impact global identity development.

It can thus be concluded that because of the exchanges, the foreign language learners progressed from awareness and understanding of being part of the global community towardsan increased felt responsibility to act and interact with others in the world as thirty-two out of eighty-four participants (38%) had demonstrated such a change. This finding also resonates with the model of global citizenship suggested by Reysen and Katzarska-Miller (2013) who pointed to global awareness as an antecedent of identification with global citizens and claimed that knowledge about the world’s affairs and one’s interrelatedness with others paves the way to identification with global community. Due to the ways in which foreign language learners began to develop global awareness and an overall global identity, incorporating virtual exchanges into coursework should be done in order to prepare L2 learners for the 21st century (Helm & Guth, 2010).

Conclusion

Postman (1995) claimed that preparing learners for global citizenship takes place through teaching them to be globally aware. Not until learners become globally aware can they form a global identity. Therefore, global identity is dependent on global awareness. Through the virtual exchanges, foreign language learners in this project recognized how people are interconnected. This interconnectedness and sense of belonging and being part of the global community allowed them to begin forming their global identity. As a result of these exchanges, not only it was evident that the participants’ development of global awareness and global identity were impacted, but also that the field of foreign language education provided a platform to promote this growth. While this study lays the groundwork as the first virtual exchange that explored the global identity construct, it is imperative that further studies be done to fully understand the opportunities that virtual exchanges provide.

Acknowledgements

In carrying out this study, the authors received assistance from their colleagues Carlos Fernando Dimeo Álvarez, Kayla Roumeliotis, and Salvador Venegas Escobar.

References

Banks, J. A. (2014). Diversity, group identity, and citizenship education in a global age. Journal of Education, 194(3), 1–12. https://doi.org/10.1177/002205741419400302

Block, D. (2009). Second language identities. London, UK: Bloomsbury Publishing.

Bohinski, C. A. & Mulé, N. (2016). Telecollaboration: Participation and negotiation of meaning in synchronous and asynchronous activities. MEXTESOL Journal, 40(3), 1–16. http://www.mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=1489

Buchan, N. R., Brewer, M. B., Grimalda, G., Wilson, R. K., Fatas, E., & Foddy, M. (2011).Global social identity and global cooperation. Psychological Science, 22(6), 821–828. https://doi.org/10.1177/0956797611409590

Burnouf, L. (2004). Global awareness and perspectives in global education. Canadian Social Studies, 38(3), 1–12. https://eric.ed.gov/?id=EJ1073942

Byram, M. (2008). From foreign language education to education for intercultural citizenship: Essays and reflections. Clevedon, UK: Multilingual Matters.

Case, R. (1993). Key elements of a global perspective. Social education, 57(6), 318–325. http://www.socialstudies.org/sites/default/files/publications/se/5706/570607.html

Chun, D. M. (2015). Language and culture learning in higher education via telecollaboration. Pedagogies: An International Journal, 10(1), 5–21. https://doi.org/10.1080/1554480X.2014.999775

Cornelius, M., & Robinson, T. N. (2011). Global identity and environmental sustainability: Related attitudes and actions. Retrieved from https://web.stanford.edu/group/peec/cgi-bin/docs/behavior/research/global%20identity%20manuscript%20final.pdf

Dooly, M., & O'Dowd, R. (2012). Researching online foreign language interaction and exchange: Theories, methods and challenges. Oxford, UK: Peter Lang.

Erez, M., Lisak, A., Harush, R., Glikson, E., Nouri, R., & Shokef, E. (2013). Going global: Developing management students' cultural intelligence and global identity in culturally diverse virtual teams. Academy of Management Learning & Education, 12(3), 330–355. https://doi.org/10.5465/amle.2012.0200

Erikson, E. H. (1967). Memorandum on youth. Daedalus, 96(3), 860–870. https://www.jstor.org/stable/20027079

Gall, M. D., Gall, J. P, & Borg, W. R. (2003). Educational research: An introduction (7th ed.). Boston, MA: Allyn and Bacon.

Gibson, S., & Reysen, S. (2013). Representations of global citizenship in a school environment. International Journal of Education Research, 8(1), 116–128. http://link.galegroup.com.libproxy.temple.edu/apps/doc/A352490719/AONE?u=temple_main&sid=AONE&xid=8d20e9bd

Godwin-Jones, R. (2015). The evolving roles of language teachers: Trained coders, local researchers, global citizens. Language, Learning and Technology, 19(1), 10–22. http://dx.doi.org/10125/44395

González-Lloret, M. (2003) Designing task-based call to promote interaction: En busca de esmeraldas. Language Learning & Technology, 7(1), 86–104. http://dx.doi.org/10125/25189

Goossens, L. (2001). Global versus domain-specific statuses in identity research: A comparison of two self-report measures. Journal of adolescence, 24(6), 681–699. https://doi.org/10.1006/jado.2001.0438

Grant, A .C. (2006). The development of global awareness in elementary students through participation in an online cross-cultural project. Retrieved from LSU Doctoral Dissertations (4058). https://digitalcommons.lsu.edu/gradschool_dissertations/4058

Hanvey, R. G. (1976). An attainable global perspective. New York, NY: Center for Global Perspectives in Education.

Harper, N. J. (2018). Locating self in place during a study abroad experience: Emerging adults, global awareness, and the Andes. Journal of Experiential Education, 41(3), 295–311. https://doi.org/10.1177/1053825918761995

Helm, F., & Guth, S. (2010). The multifarious goals of telecollaboration 2.0: Theoretical and practical implications. In S. Guth & F. Helm (Eds.), Telecollaboration 2.0: Language, literacies and intercultural learning in the 21st century (Vol. 1) (pp. 69–106). Bern, CH: Peter Lang.

Henry, A., & Goddard, A. (2015). Bicultural or hybrid? The second language identities of students on an English-mediated university program in Sweden. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 14(4), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2015.1070596

Karlberg, M. (2008). Discourse, identity, and global citizenship. Peace Review: A Journal of Social Justice, 20(3), 310–320. https://doi.org/10.1080/10402650802330139

Kohn, K., & Hoffstaedter, P. (2017). Learner agency and non-native speaker identity in pedagogical lingua franca conversations: Insights from intercultural telecollaboration in foreign language education. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 30(5), 351–367. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2017.1304966

Kirkwood, T. F. (2001). Our global age requires global education: Clarifying definitional ambiguities. The Social Studies, 92(1), 10–15. https://doi.org/10.1080/00377990109603969

Leask, B. (2015). Internationalizing the curriculum. London, UK: Routledge.

Lenkaitis, C. A. (2019). Technology as a mediating tool: Videoconferencing, L2 learning, and learner autonomy. Computer Assisted Language Learning. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2019.1572018

Lenkaitis, C.A., Calo, S., Venegas Escobar, S. (2019). Exploring the intersection of language and culture via telecollaboration: Utilizing videoconferencing for intercultural competence development. International Multilingual Research Journal, 13(2), 102–115. https://doi.org/10.1080/19313152.2019.1570772

Lenkaitis, C.A. & English, B. (2017). Technology and telenovelas: Incorporating culture and group work in the L2 classroom. MEXTESOL Journal, 41(3), 1–20. http://www.mextesol.net/journal/index.php?page=journal&id_article=2514

Maguth, B. (2014). Digital bridges for global awareness: Pre-service social studies teachers’ experiences using technology to learn from and teach Students in Thailand. Journal of International Social Studies, 4(1), 42–59. http://iajiss.org/index.php/iajiss/article/view/115

Mansoory, S. (2012). Exploring global identity in emerging adults (Master’s thesis). Retrieved from http://www.diva-portal.org/smash/record.jsf?pid=diva2%3A549930&dswid=-6385

Mu, G. M. (2015). A meta-analysis of the correlation between heritage language and ethnic identity. Journal of Multilingual and Multicultural Development, 36(3), 239-254. https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.2014.909446

Nunnally, J. C. & Bernstein, I.H. (1994). Psychological theory. New York, NY: McGraw-Hill.

O’Dowd, R. (2011). Online foreign language interaction: Moving from the periphery to the core of foreign language education?Language Teaching, 44(3), 368–380. https://doi.org/10.1017/S0261444810000194

O’Dowd, R. (2018). From telecollaboration to virtual exchange: State-of-the-art and the role of UNICollaboration in moving forward. Journal of Virtual Exchange, 1–23. https://doi.org/10.14705/rpnet.2018.jve.1

Orsini-Jones, M., Conde, B., & Altamimi, S. (2017). Integrating a MOOC into the postgraduate ELT curriculum: Reflecting on students’ beliefs with a MOOC blend. In K. Qian & S. Bax (Eds.) Beyond the language classroom: Researching MOOCs and other innovations (p. 71–83). Dublin, IE: Research-publishing.net

Orsini-Jones, M., & Lee, F. (2018). The CoCo telecollaborative project: Internationalisation at home to foster global citizenship competences. In M. Orsini-Jones & F. Lee (Eds.), Intercultural Communicative Competence for Global Citizenship(pp. 39-52). London, UK: Palgrave Macmillan.

Postman, N. (1995). The end of education: redefining the value of school. New York, NY: Knopf.

Reysen, S., & Katzarska-Miller, I. (2013). A model of global citizenship: Antecedents and outcomes. International Journal of Psychology, 48(5), 858–870. http://dx.doi.org/10.1080/00207594.2012.701749

Sandelowski, M. (2003). Tables or tableaux? The challenges of writing and reading mixed methods studies. In A. Tashakkori & C. Teddlie (Eds.), Handbook of mixed methods in social and behavioral research. (pp. 321–350). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage.

Schultheis-Moore, A., & Simon, S. (2015). Introduction: globalization in the humanities and the role of collaborative online international teaching and learning. In A. Schultheis-Moore & S. Simon (Eds.), Globally Networked Teaching in the Humanities. Theories and Practices. (pp. 13–22). New York, NY: Routledge.

Thirunarayanan, M. O. & Coccaro-Pons, J. (2016). A global information exchange (GIE) project in a graduate course. TechTrends, 60(3), 289–298. https://doi.org/10.1007/s11528-016-0051-6

Ushioda, E. (2011). Language learning motivation, self and identity: Current theoretical perspectives. Computer Assisted Language Learning, 24(3), 199–210. https://doi.org/10.1080/09588221.2010.538701

Wagner, T. (2014). The global achievement gap: Why even our best schools don't teach the new survival skills our children need and what we can do about it. New York: Basic Books.

Walker, G. (2006). Educating the global citizen. Suffolk, UK: John Catt Educational.

Wang, J., Peyvandi, A., & Coffey, B. S. (2014). Does a study abroad class make a difference in a student’s global awareness? An empirical study. International Journal of Education Research, 9(1), 151-162.

Westjohn, S. A., Arnold, M. J., Magnusson, P., Zdravkovic, S., & Zhou, J. X. (2009). Technology readiness and usage: A global-identity perspective. Journal of the Academy of Marketing Science, 37(3), 250–265. http://dx.doi.org/10.1007/s11747-008-0130-0

Zhao, Y. (2010). Preparing globally competent teachers: A new imperative for teacher education. Journal of Teacher Education 61(5), 422–431. https://doi.org/10.1177/0022487110375802

Zong, G. (2009). Developing preservice teachers' global understanding through computer-mediated communication technology. Teaching and Teacher Education, 25(5), 617–625. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.tate.2008.09.016

[6] Prior to a name change due to marriage, Chesla used her maiden name, Bohinski, for publications.

[5] The term virtual exchange is becoming the term commonly used when describing an exchange among partners from different cultural contexts and geographic locations. Other terms under the virtual exchange umbrella include telecollaboration, online intercultural exchanges, and teletandem (O’Dowd, 2018).