Introduction

Project-based language learning (PBLL) is a comprehensive, enriching pedagogical approach that can engage and empower students by developing academic skills such as planning, researching, analyzing, synthesizing, producing, and reflecting, all while developing language and content knowledge. Research on PBLL suggests that participating in projects can build decision-making skills and foster independence while enhancing cooperative work skills, challenge students’ creativity, and improve problem-solving skills (Beckett & Slater, 2018a). Used in second language teaching, PBLL’s student-centered approach offers learners opportunities to learn and produce language authentically in real-world contexts, work collaboratively, and focus on what they are interested in and needing to learn (Alan & Stoller, 2005; Habók & Nagy, 2016). Participating in PBLL can also provide natural contexts for the learning of appropriate technology for authentic purposes. PBLL is a sound pedagogy through which learners can use language as a medium to learn language form, content, and sociocultural knowledge. This article combines two frameworks for PBLL to detail a project that develops language through the content topic of applying for American graduate schools; this project is presented in the Appendix for readers to use.

PBLL is based on John Dewey’s experiential learning philosophy as well as multiple frameworks that are reflected in social constructivist learning theories that consider knowledge construction as social practice (Vygotsky, 1978). Following this view and working within a systemic functional linguistic perspective, Mohan (1986) adopted the concept of a social practiceor activityas his unit of analysis and explained how content, language, and key visuals are integrated through participation in social practices. Mohan provided a knowledge frameworkfor an activity (described below), showing how this could serve as a heuristic for unit planning within PBLL and other teaching contexts.

Despite research findings showing that students enjoy doing projects and learn a great deal of language, many reports have suggested that students have difficulty seeing how language is being developed through this approach (e.g., Beckett, 1999; Tang, 2012). Consequently, Beckett and Slater (2005) advocated for a framework to conceptualize how projects can develop language. They built on Mohan’s work to create The Project Framework, which included a classification visual and a project diary that could help students understand how participation in this type of social practice could help them learn content and language while honing their academic skills. Here we blend Beckett and Slater’s Project Frameworkwith Mohan’s knowledge framework to describe a PBLL unit teachers can use as is or as a model for future units.

Our unit provides a detailed example to argue that looking at PBLL as a social practice, as conceptualized from Dewey and Mohan, can be instrumental in planning a variety of project-based language teaching units that can provide transparency for the development of language, content, thinking skills, and technology. Our PBLL plan engages students in language development and content learning while examining the use of various technological affordances. We have highlighted the learning and use of technology not only in response to Finch and Daegu (2012), who called for the infusion of technology into PBLL, but also for a variety of other reasons. First, there is a considerable amount of research showing that the inclusion of technology in projects is motivating for students (see, for example, Beckett & Slater, 2018b) and results in higher achievement (e.g., Darling-Hammond, Zielezinski, & Goldman, 2014). Second, students have reported that they believe the inclusion of technology in project-based curricula to be useful and relevant to their future education and careers (e.g., Mosier, Bradley-Levine, & Perkins, 2016). Third, the use of technology within a PBLL approach has been seen to improve students’ disciplinary literacy (e.g., Hafner, 2014). Fourth, just as there have been reports of students not clearly seeing the value of projects for language learning, as mentioned above, there have been similar findings concerning the use of technology in these classes (e.g., Terrazas-Arellanes, Knox, & Walden, 2015). Thus, our unit plan suggests technology that can explicitly facilitate the learning of content and technology while developing the language needed for the various tasks.

Below, we provide a description of both Mohan’s knowledge framework and Beckett and Slater’s (2005) Project Framework and blend them to show how teachers can ensure their students learn language and understand how project participation aids this process. These descriptions will be followed by our suggestions for lessons that explicitly reflect these frameworks. Because the topics in the PBLL approach must relate to students’ real-world motivation, needs, and goals as suggested above, the topic we have chosen to detail here aims to address a very cultural practice that may be of interest and importance to many students in EFL contexts, using English and technology to apply to American graduate schools.

Mohan’s knowledge framework

A knowledge framework (KF), is a heuristic of a social practice or activity, a chart that can help teachers organize their unit’s lessons, tasks, and content to ensure they address not only content learning objectives but also language goals. Mohan described an activity as “a combination of action and theoretical understanding” (Mohan, 1986, p. 42), thus emphasizing the concepts of doing (action) and knowing (theoretical understanding). In educational practice, we acknowledge this as a connection between the tasks students undertake and the content and linguistic knowledge they need to complete these tasks. Mohan’s simple heuristic of a knowledge framework with its six boxes is expanded in Table 1 to list the knowledge structures and the thinking skills, key visuals, and characteristic language associated with them.

Table 1: The knowledge structures, thinking skills, key visuals, and language of Mohan’s knowledge framework (based on Early, 1990, and Mohan, 1986)

As shown in the column on the left, the KF consists of six of what Mohan calls knowledge structures (KSs). Each of these KSs has thinking skills and language associated with it, and each has common key visuals or graphic organizers that show the structure multimodally. Classification,for example, involves classifying, defining, and examining part-whole relationships and can be visualized using tree diagrams, webs, and tables. Linguistically, it involves verbs such as beand haveand lexis such as type, sort, divide, comprise, classify,and group.Descriptionis similar in its verb use but makes wide use of adjectives and other attributive words as well as comparative words, and can utilize visuals such as pictures, Venn diagrams, and pie charts. The KS of Sequenceinvolves the ordering of events or things and can be visualized through a timeline, list, or comic strip. The language associated with this KS includes most notably adverbs such as first, then, after, before,and finally,but sequence also involves many action verbs such as send, go, prepare, write,and readas well as verbs that explicitly show a sequence, such as start, finish,and continue. Examples of nouns that clearly denote a sequence are beginning, end, summary,and conclusion. Certain adverbial clauses also fit this KS, such as when-clauses or phrases that state when and even where something occurs (e.g., in summer, on the Internet). The thinking skills that make up one of the most important KSs for graduate school, Principles, have to do in part with explaining, testing and hypothesizing, and establishing causes, effects, means, and ends. Its visual options are often cause/effect chains and problem/solution graphics. The lexis that builds the thinking skills of this KS are terms such as cause, effect, result, produce, consequently, due to, and if-clauses. Finally, Choiceand Evaluationconcern decision-making and evaluating. The former uses lexis such as opt, choice, select, prefer,and the question word which, whereas the latter suggests more evaluative words such as rank, approve, value, best, boring,and even the ubiquitous like.

These KSs occur across a wide variety of topics and activities and can therefore be considered cross-curricular. The language that is used to construct each KS, regardless of the content area, is similar and uses much of the same key vocabulary and grammar. This offers teachers and their students a valuable toolbox for learning and using the language of these KSs across any content area. To offer a concrete example, regardless of whether an instructor is teaching students the timeline for submitting application documents or how to bake cookies (dramatically different content areas), each lesson naturally encourages students to use the language of sequence alongside vocabulary relevant to the content (e.g., application, CV, letters of recommendationv vs. chocolate chips, flour, sugar). It may thus be in the best interest of the instructor to exploit this connection to teach new and perhaps more academic language that constructs each KS, rather than leaving their students to use only what they already know, focusing only on vocabulary or random grammar exercises, or simply leaving the language-learning process up to incidental acquisition and adding to students’ confusion about how the project assists them in their language development.

The Project Framework Applied

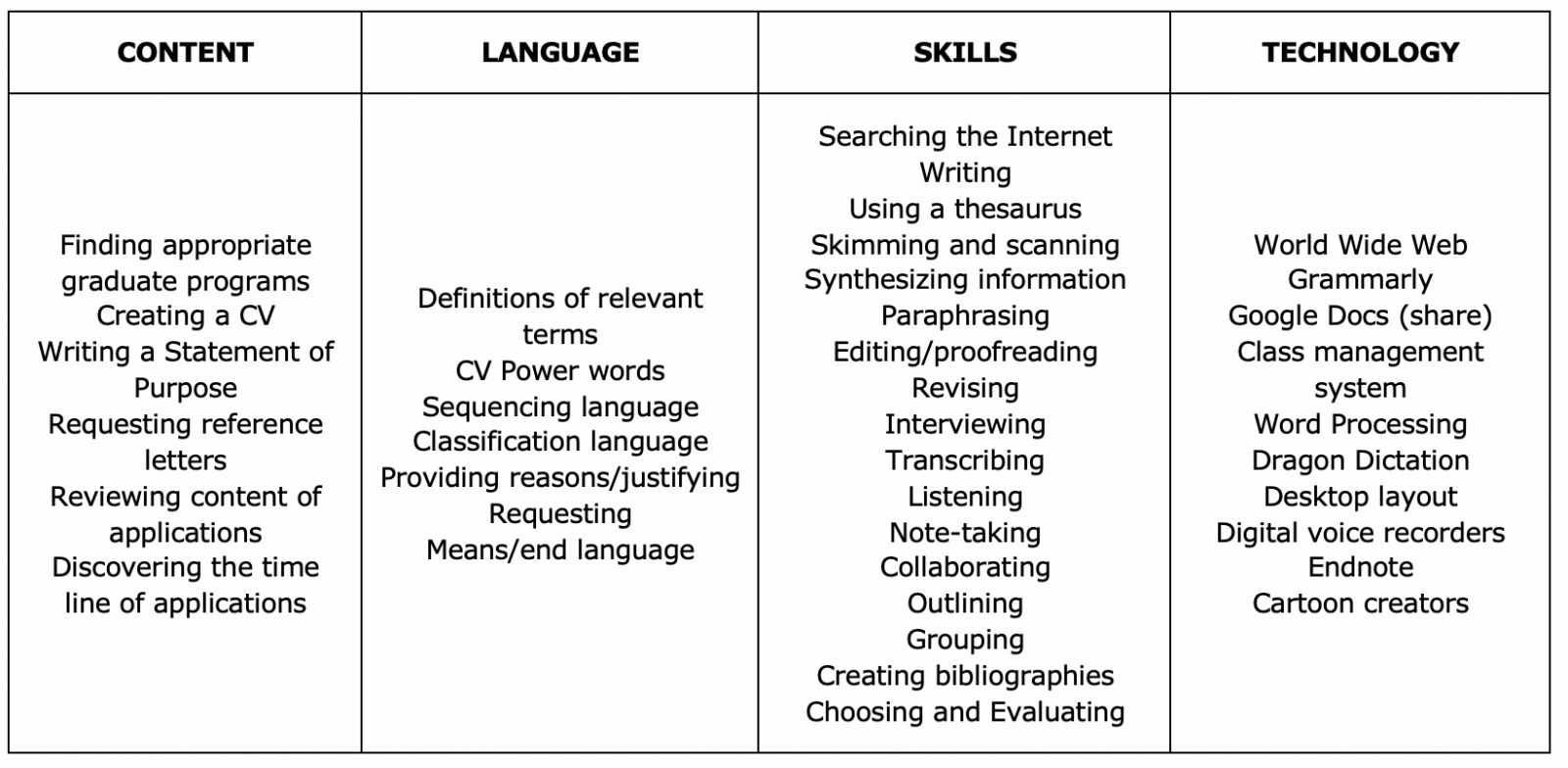

Beckett and Slater (2005) advocated for the creation of a framework that would help students envision a new way to look at language learning and provide an explicit way to illustrate how engaging in project work on any topic allows for the simultaneous development of language, content, and skills. The Project Framework has two components: the planning graphic and the project diary. In Table 2 below, we cite Beckett and Slater’s (2017) revised planning graphic as it has been applied to the graduate school application unit. This graphic includes the development of technology knowledge (note that instructors can teach other tools beyond what is suggested). The Framework allows for brainstorming and planning the types of knowledge the instructor wishes to focus on, use, or teach during the unit, and should be considered the first step in creating the unit plan once the overall content area has been determined.

Table 2: Revised Project Framework (Beckett & Slater, 2017)

Once the knowledge and content goals have been categorized as above, the next step is to consider questions that can be asked around the content itself. These questions should reflect the information the teacher would like students to learn. In our unit, for example, questions that may be asked are what kinds of US graduate programs are available and appropriate for these students? What past accomplishments compel students to apply for programs? What types of requirements do students need to meet to be accepted into a program? When are the deadlines and what needs to be submitted by these deadlines? These types of questions can be brainstormed with students when filling out the initial Project Framework, as in Table 2 above, or they can originate from the instructor. The important aspect is organizing these ideas prior to setting up the unit plan.

Blending the Two Frameworks

The brainstormed questions from above can be classified according to the language used to construct them, because the wording suggests specific knowledge structures, as we show in the knowledge framework in Table 3 below. Having the various questions in a KF format allows teachers to emphasize the focus on language, as each knowledge structure has language that constructs it, as stated earlier.

Table 3: A knowledge framework of questions for graduate school applications

Taken together, the Project Framework and the knowledge framework as we have described above provide guidance in creating the unit with its individual lessons and tasks, in that the target knowledge in the Project Framework (content, language, skills, and technology) can be combined with the knowledge-structure questions from the KF, allowing for explicit connections to be made between language and content. Appropriate technology tools such as the ones suggested in Table 2 above can be adopted to help students find the content information they need as well as read, construct, and practice language with those tools, and the skill development that is targeted can inform the type of work (reading, group work, information gap tasks, etc.) that teachers incorporate into the lessons.

The outcome of the project is a successful application to a graduate school in the United States, and this requires several subtasks including creating a CV, choosing the best institution(s) to apply to, writing a statement of purpose, and requesting reference letters, as noted in the content column of Table 2. Each lesson in some way must lead to the successful completion of these tasks, but because the students are in a language-learning environment that also teaches technology, each lesson must also explicitly show how it focuses on language and skill development (academic, personal, and technological). The unit plan thus blends the columns from the Project Framework with the integrated language and content knowledge structures of the KF.

An illustration of practice: The organization of our unit

Based on the combination of Mohan’s KF and Beckett and Slater’s Project Framework, what follows are suggestions for eleven lesson plans, in recommended order, although the unit (as shown in Appendix A) may be expanded.

1. Establishing the sequence for applying

2. Determining needs and wants

3. Identifying important elements of a CV

4. CV: Telling a life story

5. Creating a CV: From your life story to a CV

6. Finishing up the CV: Publication records

7. Examining program characteristics of your top choices

8. What programs offer

9. Describing yourself academically and professionally

10. Writing your statement of purpose

11. Requesting letters of recommendation

Each detailed plan in Appendix A states learning outcomes and includes potential tasks that aim to address them. Along with these suggested tasks, each plan identifies relevant technology and the linguistic knowledge structure(s) in focus (all KSs will occur naturally in all lessons, but each lesson should highlight the development of a limited number of KS language resources). Although the language level can be adjusted because all knowledge structures have various linguistic resources that can be used, our suggestions acknowledge that students applying for graduate schools already meet or are close to meeting basic TOEFL requirements. We believe also that these students would be interested in, and thus motivated by, this unit to hone their language ability while learning how to submit a successful application.

Assessment of the blended frameworks project

Assessment should be both formative and summative. The instructor can proofread the final product prior to students sending it out to universities, and through this determine an acceptable summative evaluation. Formatively, we recommend a “project diary” for students, as advocated in Beckett and Slater (2005), so that students themselves see the value of doing project work for learning. Instructors should also pay close attention to the learning outcomes of each lesson and keep notes on whether the students have met these.

Conclusion

This article has recommended the blending of two frameworks, Beckett and Slater’s (2005) Project Framework and Mohan’s (1986) knowledge framework, to illustrate how a project-based approach to language teaching and learning can be adopted to explicitly highlight the complex teaching and learning goals of language, content, skills, and technology use. The unit plan as suggested here is by no means inclusive of all ideas that an instructor could use to teach students about applying to American graduate school programs, but we believe it illustrates how the two frameworks can be blended to ensure that students are developing language, content, skills, and technological savvy as they work through the various lessons. This unit plan provides a model for future units as well, particularly those that revolve around teaching and learning academic content. Because the use of projects in language classrooms targets not only language acquisition but the learning of content and various other skills as we have concluded from our examination of the research literature, we argue that by explicitly blending the Project Framework with Mohan’s knowledge framework, students and teachers together will see how this type of PBLL approach can be both educational and transformative.

References

Alan, B., & Stoller, F. L. (2005). Maximizing the benefits of project work in foreign language classrooms. English Teaching Forum, 43(4), 10-21.

Beckett, G.H. (1999). Project-based instruction in a Canadian secondary school’s ESL classes: Goals and evaluations. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). University of British Columbia, Canada.

Beckett, G.H., & Slater, T. (2005). The project framework: A tool for language, content, and skills integration. ELT journal, 59(2), 108-116. doi: https://doi.org/10.1093/eltj/cci023

Beckett, G.H., & Slater, T. (2017, March). A synthesis of project-based language learning: Research-based teaching ideas. Paper presented at TESOL2017, Seattle, Washington, USA.

Beckett, G. H., & Slater, T. (2018a). Project-based learning and technology. In J. I. Liontas (Ed.), The TESOL encyclopedia of English language teaching (pp. 1-7). Oxford, UK: Wiley Blackwell. doi: 10.1002/9781118784235

Beckett, G. H., & Slater, T. (2018b). Technology-integrated project-based language learning. In C. Chapelle (Ed.), The encyclopedia of applied linguistics (pp.1-8).Oxford, UK: Wiley-Blackwell. doi: 10.1002/9781405198431.wbeal1487

Darling-Hammond, L., Zielezinski, M. B., & Goldman, S. (2014). Using technology to support at-risk students’ learning. Scope: Stanford Center for Opportunity Policy in Education.

Early, M. (1990). Enabling first and second language learners in the classroom. Language Arts, 67, 567-574.

Finch, E., & Daegu, G. (2012). Projects for special purposes: A progress report. World Journal of English Language, 2(1), 2–13. doi: https://doi.org/10.5430.wjel.v2n1p2

Habók, A., & Nagy, J. (2016). In-service teachers’ perceptions of project-based learning. SpringerPlus, 5(83). doi: 10.1186/s40064-016-1725-4

Hafner, C. A. (2014). Embedding digital literacies in English language teaching: Students’ digital video projects as multimodal ensembles. TESOL Quarterly, 48(4), 655-685. doi: 10.1002/tesq.138

Mohan, B. A. (1986). Language and content.Reading, MA: Addison-Wesley.

Mosier, G. G., Bradley-Levine, J., & Perkins, T. (2016). Students’ perceptions of project-based learning within the New Tech School model. International Journal of Education Reform, 25(1), 2-15.

Tang, X. (2012). Language, discipline or task? A comparison study of the effectiveness of different methods for delivering content-based instructions to EFL students of business studies. (Unpublished doctoral dissertation). Durham University, Durham, UK.

Terrazas-Arellanes, F. E., Knox, C., & Walden, E. (2015). Pilot study on the feasibility and indicator effects of collaborative online projects on science learning for English learners. International Journal of Information and Communication Technology Education, 11(4), 31-50. doi: 10.4018/JICTE.2015100103

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Interaction between learning and development (M. Lopez-Morillas, Trans.). In M. Cole, V. John-Steiner, S. Scribner, and E. Souberman (Eds.) Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes (pp. 79-91). Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.