Think of a Pop quiz with the following questions. Can you play the piano? Can you ride a bike? Your answers will express the level of expertise (competence) you are using to complete the task. If your answers are affirmative, this may mean that your attitude is positive because: a) you play the piano well; b) you learned how to by doing it, seeing others do it, or listening to it; or c) you are talented. If you answered no, it could mean: a) you have not performed the action well, or accurately; b) you have not learned how to do it; or c) you were not gifted with such a talent. In this way, a performance can be seen as something learned, or a talent as part of a competence - the ability to perform a specific task, action or function successfully. We can think of this situation as a basic competence or generic competence.

Playing the piano, for example, is the execution of an instrument to make music. If you play the piano, you are a competent player or a talented person. You have the ability to do it. This ability is due to two possible factors: a) an innate talent that allows you naturally to perform the task or b) you learned how to do the task when someone showed you, or commanded you to do it (that is, a disciplinary competence).

As English teachers in ESL/EFL classrooms, we are urged to show, illustrate, or command our students about the task(s) or action(s) required to communicate with others, and how to do so in order to properly complete a task successfully. Completing the task, requires students to use a basic skill such as listening/speaking, reading/writing (generic competence). They may also use disciplinary competencies such as knowing, comprehending, applying, analyzing, synthesizing, summarizing, apprehending, assessing, and so on. The question is whether our students are prepared to work competently in the classroom. Have they learned efficiently and effectively how to perform the task by themselves? Do they have the right kind of skills to handle the task? If students lack the skills to tackle such tasks, they will most likely fail.

Basic definition of competence

Chomsky (1965) coined the term competence to account for the unconscious knowledge speakers have of their language. Not only does it refer to the performance of specific tasks, but how the language relates to the grammatical or psychological aspects of itself and the mental representation of the language (Fromkin & Rodman, 1981). Thus, Chomsky refers to what other researchers call linguistic competence (O’Grady, et al. 1993) which discusses a psychological or mental property or function (Lyons, 1996). On the other hand, researchers such as Hymes (1974) propose the term “communicative competence” as the sociolinguistic usage of the language. A communicative skill is completed with a linguistic skill allowing students to interact not only in the classroom but also in the daily life activities of the second language.

ESL/EFL classroom teachers are requested to not only provide linguistic tools (e.g., grammar rules, vocabulary, phonics), but also the communicative tools needed to improve accuracy in students’ speaking abilities. Teachers must search for ways to perform tasks in a second language similar to those they would use in their mother tongue. That is, strategies from the former language can certainly support aspects of these strategies in the second language.

One example of a competency guideline is SCANS (Secretary of Commission on Achieving Necessary Skills) by the U.S. Department of Labor (1993). This program states that:

SCANS is made up of five competencies and a three-part foundation of skills and personal qualities needed for solid job performance. These competencies include: a) Resources including the allocation of time, money, materials, space, staff; b) Interpersonal Skills which involve working on teams, teaching others, serving customers, leading, negotiating, and working well with people from culturally diverse backgrounds; c) Information which requires acquiring and evaluating data, organizing and maintaining files, interpreting and communication and using computers to process-information; d) Systems which include understanding social, organizational, and technological systems, monitoring and correcting performance, and designing or improving systems; and, e) Technology which involves selecting equipment and tools, applying technology to specific tasks, and maintaining and troubleshooting technologies. THE FOUNDATION, on the other hand, includes: a) Basic Skills such as reading, writing, arithmetic and mathematics, speaking and listening; b) Thinking Skills such as thinking creatively, making decisions, solving problems, seeing things in the mind’s eye, knowing: how to learn, and reasoning; and c) Personal Qualities such as individual responsibility, self-esteem, sociability, self-management and integrity. (SCANS, 1993, p. 6)

Another program is CASAS (2003) which states:

Programs can use the CASAS competencies in developing a standards-based curriculumthat better meets learner, community, and program needs and helps fulfill federal, state,and local reporting requirements. CASAS assessment measures competencies in functional contexts. Items measuring the same competency can be targeted to one or more instructional levels. (p. 2)

Test items can also be presented in a variety of task types. These may include forms, charts (e.g., maps, consumer billings, matrices, graphs or tables), articles, paragraphs, sentences, directions, manuals, signs (e.g., price tags, advertisements or product labels), and measurement scales or diagrams (CASAS, 2003). Such ways of working (CASAS or SCANS) to improve a language, mother tongue or a second language, would be intended in the English classes programs from the Centro de Bachillerato Tecnológico Industrial y de Servicios (CBTIS) courses to promote a better way of learning or acquiring a foreign language. Neither CASAS nor SCANS has been taken into consideration to fulfill English program courses from Dirección General de Educación Tecnológica Industrial (DGETI).

Instead, English programs from DGETI are based upon the Canadian Language Benchmarks (2000) and, accordingly, to the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages Learning, and Teaching, Assessment. This attempt demonstrates a way in which to model an educational trait from outside and adapt/adopt it to improve the teaching practice of English teachers in Mexico. An example of a generic competency from the English courses is competency # 4: listen, interpret and issue relevant messages in different contexts by utilizing media, codes and appropriate tools (escucha, interpreta y emite mensajes pertinentes en distintos contextos mediante la utilización de medios, códigos y herramientas apropiados) where students apply different strategies in order to acquire the required competency(ies) (see Table 1, COSDAC, 2012).

Table 1. Generic competency example

The vehicle to perform such development of a competency is a “didactic sequence” which is a tool to be used with the task(s) involved in acquiring the specific competency(ies). This didactic sequence is related to the scope and sequence used in the American educational system. Therefore, the didactic sequence becomes a possible reference to work within the lesson plan of the teaching practice in Mexico. For this reason, this tool or instrument is the one used in the DGETI planning to allow the performance of items such as competencies. In this way, it is hoped that students will carry out certain specific competency(ies) according to the required performance(s). These performances are regulated in such guidelines as SCANS, CASAS, and others.

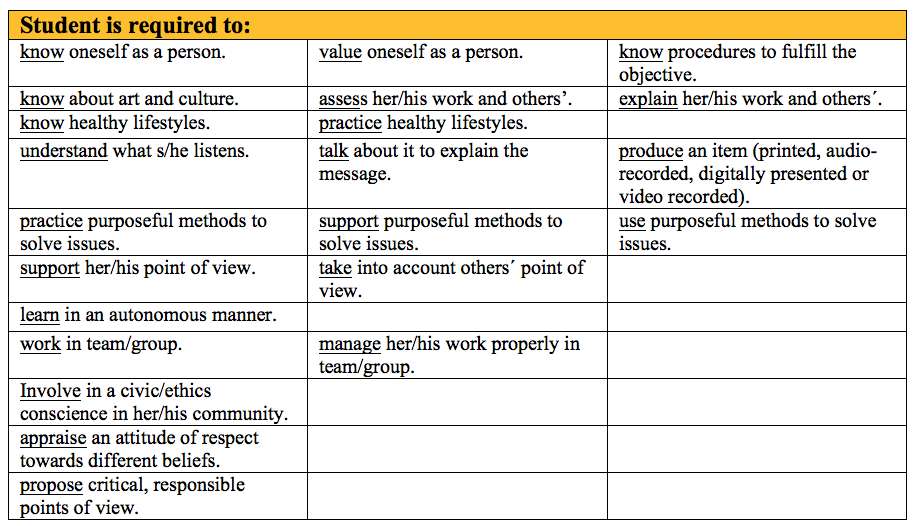

In this way, generic competences are related to what the student is going to develop during the different courses. Table 2 below shows the different skills each student should learn. Each skill suggested is expressed as an action (a verb) in accordance with Bloom’s Taxonomy. In this sense, teachers should consider each competency to be related to different language skills (see Appendix 1):

Table 2. Skills needed by students

Competencies suggest what students should learn which include: being a self learner; working cooperatively, collaboratively and effectively; and learning content in a second language to communicate successfully.

Competence vs. Performance

What is the ideal strategy to use within the ESL/EFL classroom for a teacher? As English teachers, we are committed to making students perform tasks using daily life facts/or activities. Students must perform tasks which are similar to the ones in their first language (Spanish), in order to pick up such skills for the second language (English). Competency # 7 - Student learns initiative and self-interest throughout life--would be an example of these daily life tasks. Students must understand that they are dealing with daily life issues in a second language. That is, students need to be aware of the most common vocabulary in use in daily life activities. For example, are students aware of the term “toilet tissue?” What is it in Spanish? Are they familiar with polite and formal ways of requesting information? Do they know the polite use of “May I…?”

What is intended, in this case, is that students practice and acquire basic common polite ways of speaking as if they actually were native speakers. Students’ skills in L1 are the background with which a learner helps to solve her/his own needs in the ESL/EFL classroom. In other words, they determine what a student can express, reflect or develop in a second language just as a student might do in her/his native language This allows students to understand that competencies are the same for both native and second languages. They learn this: a) by using the terms, b) in a certain context, c) acquired as if they were from the native context, and d) are learned explicitly within the classroom.

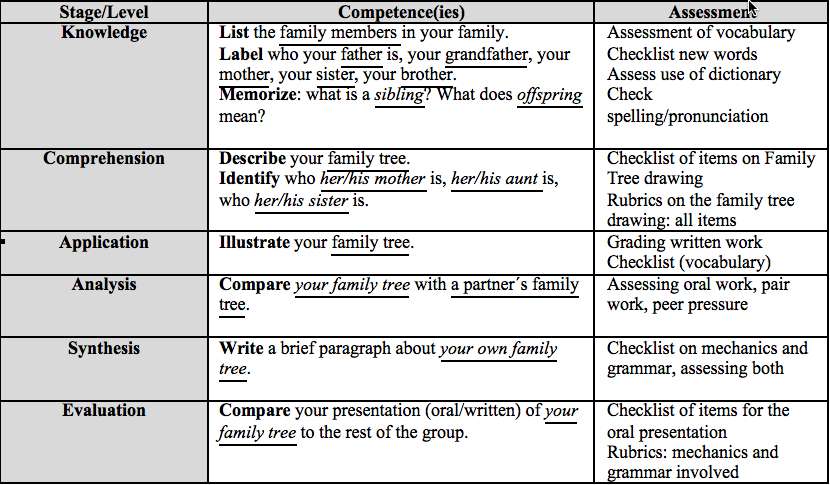

Basic skills, as well as higher order thinking skills, are viewed as the pattern to make students capture such linguistic/sociological items. Competencies, as viewed in the DGETI programs, show the elements involved in teaching by using students’ own skills to improve new strategies to learn a second language. Benjamin Bloom (1956) developed a classification of levels of intellectual behavior which are important in learning (Office Port, 2002). He identified six levels of cognitive domain: knowledge, comprehension, application, analysis, synthesis, and evaluation. Each level is described by verbs representing what students should be able to do to perform each task at a given level. Each level also contains question categories with those intellectual schemes students must practice and assume. In this way, actions go from the basic skills to more complex (see Table 3). Students must demonstrate the competency(ies) not only in a mechanical way, but they are also able to demonstrate the skills required by each category.

Table 3. Bloom’s (1956) Levels of Cognitive Domain

What is expected in the ESL/EFL classroom is that students complete the tasks and at the same time, produce something new as a result of their own learning. It is no longer sufficient simply to memorize material, read and repeat scripted dialogs in texts, or perform multiple choice tests. This new approach requires students to activate higher order thinking skills and to actually be able to use the language in real contexts based on the knowledge they have gained through classroom study. Bloom’s Taxonomy Verbs Wheel provides an illustration of what students need to produce at each level of thinking (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. Bloom’s Taxonomy Verbs Wheel (Ferlazzo, 2009)

The domain, represented by the innermost circle, refers to one of the specific skills outlined in the table above. In the knowledge stage, students must recall, recognize and remember. At this level, students would know how to translate vocabulary words from one language to the other. In the comprehension stage, students must demonstrate an understanding of the facts. Here, they go beyond recall and recognition to beginning to use the language by, for example, being able to summarize information in a chart or graph. In the application stage, students apply knowledge to actual situations by using their own skills to develop learning strategies. For example, a student might have to make a complaint about a health problem using knowledge of vocabulary, rules of politeness, grammar, and linguistic conventions.

From here, thinking transitions into higher order thinking skills. In the analysis stage, students must break down objects or ideas into simpler parts and find evidence to support generalizations. Here, students are asked to analyze an argument or a point of view in order to understand it better. This could involve, for example, deciding which plan for a party is the best one. In the synthesis stage, students must compile component ideas into a new whole or propose alternative solutions. This skill requires a very high level of critical thinking ability. An example of such a task might be to have students study a particular social problem and then propose an effective way to deal with the situation. Finally, in the evaluation stage, students must make and defend judgments based on internal evidence or external criteria. This represents the highest level of critical thinking and requires students, for example, to study a topic, understand it, and defend the position to others who may not share this point of view. This could include students deciding on who is the best music group and then defending that view.

From this, it is possible to see that students must go beyond simply memorizing grammar rules or vocabulary. Instead, they must be able to use the language in context. They must be able to apply those grammar rules and that vocabulary in a way that makes sense in the second language situation. This engages the students thinking skills and moves toward a greater understanding and more effective use of language.

What competencies are supported in my English course?

An English course should be based upon the four functions of the language: listening-speaking, reading-writing. In Trends (Llanas, 2010), the English course I am working with right now, there are six generic competencies. The first is Me which refers to evaluating her/himself and her/his place, expressing her/his emotions accurately, and being able to react (acceptance). The second, Communicate, refers to giving the strategies needed to express both oral and written ideas. The next, Think, refers to understanding grammar. Collaborate refers to promoting the ability to work in teams and involves the idea of cooperative learning. Learn refers to developing the ability to formulate rules from the understood grammar (scaffolding). The last one, Act, refers to giving the learner global awareness and encouraging her/him to respect others´ ideas/beliefs.

All these generic competencies are suggested to provide a way to interact with the teacher, but also with other students, and other faculty members as well, within/outside the classroom. The students’ performance in the second language will require the student to activate first language (and cultural) skills along with second language skills in order to complete any given task. These competencies differ from the generic competencies given by SEP, Reforma Integral (Comprehensive Reform) because Trends competencies are expressed as action verbs.

This provides an environment where students are able to do, see others do, or listen to what they do. English teachers must commit themselves to developing strategies with which students not only listen, speak, read, write but also evaluate, express, understand, cooperate, formulate, encourage, and interact, and so on (disciplinary competencies). In other words, students must move from lower order thinking skills and performances to those higher order thinking skills, reflected in the taxonomy above.

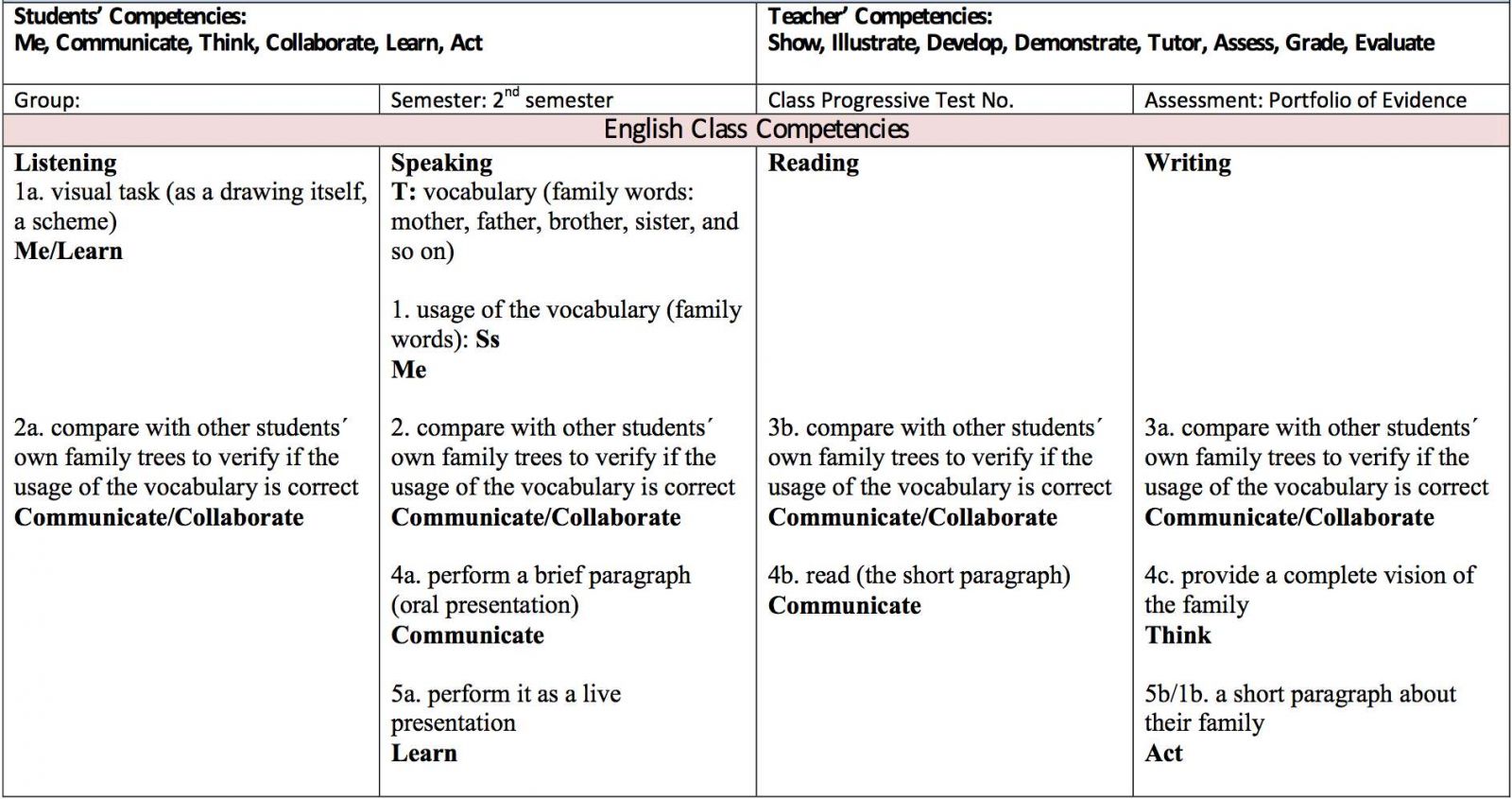

An example of my current course, reflecting both basic and higher order thinking skills, appears in Figure 2 below (Llanas, 2010).

Figure 2. Textbook Examples of Competencies

Working with competences in the ESL/EFL classroom

The educational policies in Mexico have reorganized the way English classes are taught. Mexico´s educational policies have used different benchmarks including the Canadian Language Benchmarks 2000 (Paulikoska-Smith, 2000). Sosa and Toledo Hermosillo (2004) consider another benchmark from Spain or Argentina, which is not clearly defined, and is vaguely based upon the works of José Bleger (1983). The highlights of this proposal refer to the attitudes and values that students must consider when practicing the language. The benchmark related to this update involving the Common European Framework of Reference for Language Learning was taken from the Centro Virtual Cervantes (1997) in Madrid. It describes the skills necessary to attain a given level of proficiency. As a result, English classes in the High School system have transitioned from a more traditional grammar-translation focus to a more communicative one reflecting the move from basic skills (knowledge and comprehension) to higher order skills (analysis, synthesis, and evaluation). The focus of the methodology is based upon getting students to gain the ability to actually use language in context and to produce real authentic language. The goal is to let students interact with a variety of materials (e.g., oral/recorded presentations poems, comic strips, short stories, pamphlets, dioramas) in the second language by using their mother tongue as a reference.

In a communicative English course, students listen, speak, write, read, as well as evaluate, express, understand, cooperate, formulate, encourage, and interact with facts related to the target language. Students practice what they can do by using the skills from their native language. The purpose is to help students develop a second language (and the tasks emerging from this learning such as answering the phone, interacting in a conversation, or completing any printed form as questionnaires, surveys, and so on) and also to learn the necessary linguistic elements to communicate appropriately and transform the results obtained from the learning itself or the tasks completed as their own way of communicating in a second language effectively. In this way, students practice their generic skills as well as their higher order thinking skills.

Jeremy Harmer (1987) suggests that teachers must show students the topic (a presentation). The methods of illustration could include a chart, a dialogue, a “mini-situation” a text for contrast, or a text for grammar explanation, or visuals for situations (pp.17-24). In the example below, I use a poster of a family tree in order to represent what students may learn about family. As an introductory activity, students draw their family tree. By doing this they are relating information previously known from their mother tongue into the second language understanding and using vocabulary such as mother, father, brother, sister. This is a knowledge skill. They also perform a visual task by actually drawing the tree expressing those family relationships. Here, we move into the comprehension area of the taxonomy as students create a diagram. However, in order to complete the competency and assess it, students must check the adequacy of their vocabulary, compare with other students´ own family trees to the accuracy of their vocabulary use, and deliver an oral presentation of their family tree. They must not only show visual information (the family tree diagram) but also create a structured piece of writing in the form of a paragraph. Students may then either read their paragraph or deliver an oral presentation without reading the scripted paragraph. Here students begin to transition to the higher order skills of application and evaluation. The oral presentation may include the use of a variety of tools including PowerPoint or audio recording tools (e.g., voxopop, voicethread, vocaroo) to leave recorded messages with or without illustrations. In this way, students learn the skill of creating illustrations and written messages with a minimum outlay of time and energy. In other words, they learn how to effectively use and manage their time.

How can a teacher implement such skills into practice? As a pragmatic teacher, I am aware of the importance of giving my students daily life situations concerning factual information that they already know. Table 4 shows specific information related to the competencies from the ESL/EFL class. This chart helps to take into account what competencies are reflected for both the students and the teacher. At the end of the task, the teacher can review to see if students have completed the competency requested for each functional aspect. Teachers can also help themselves by using the below table when they are about to assess each student’s own work.

.jpg)

Table 4. Working with Competencies in the Classroom

In the example above, there is an effective pace with which students will be comfortable and, at the same time, I am willing to make them practice what they are interested in. In the example below, I consider my own practice. Table 5 shows the previous activity with the usage of Bloom’s levels of cognitive domain. Notice that the actions (actually, the verbs) reflect the competence required. Actions evolve from simpler to more intrinsically planned activities. A general assessment of the course is related to the complementary information in the shape of checklists and rubrics to evaluate, grade or assess each task performed by the students. Students can get involved in considering the different elements to assess when designing the checklists and rubrics. An example of items contained in a checklist and its corresponding rubric is shown below in Table 5.

Table 5. The family tree activity using Bloom’s Levels of Cognitive Domain

In this way, a checklist will include items which students must answer and will reflect the various levels of learning. Consider, for example, the following:

1. The knowledge dimension is represented by such skills as listing, labeling, and memorizing. The following questions provide examples of these skills. Do you live with your parents? Do you live with your brothers/sisters? How many family members do you live with?;

2. Comprehension involves the students’ ability to describe and identify their own families. These skills could be determined using the following questions. Is your family nuclear or extended (do you live with your parents and siblings? or do you live with grandparents, aunt/uncle?);

3. Application includes the ability to apply information to a specific situation. In this case, having a student illustrate his/her family tree using the key vocabulary words and locating people in the proper positions would indicate that this skill has been mastered.

4. Analysis requires students to compare their performance with others. This could be done asking students make comparisons between his/her family tree and that of a classmate.

5. Synthesis is the skill of being able to take information and, for example, determine patterns. It involves putting information together in new and original ways. Students could, as a demonstration of this ability, write a paragraph about their family which might show how it relates to other families or whether it conforms to “typical” family structures.

Finally, evaluation included the ability to assess. In this example, this might include an evaluation of the family structure or talking about different types or sizes of families and listing the strengths and weaknesses of each. In this way, we can clearly see that students have progressed through each of the thinking levels and that they have mastered the vocabulary to do so.

To help assess these abilities, a rubric should be created. Items for a rubric might include the following:

Table 6. Rubric for Evaluation

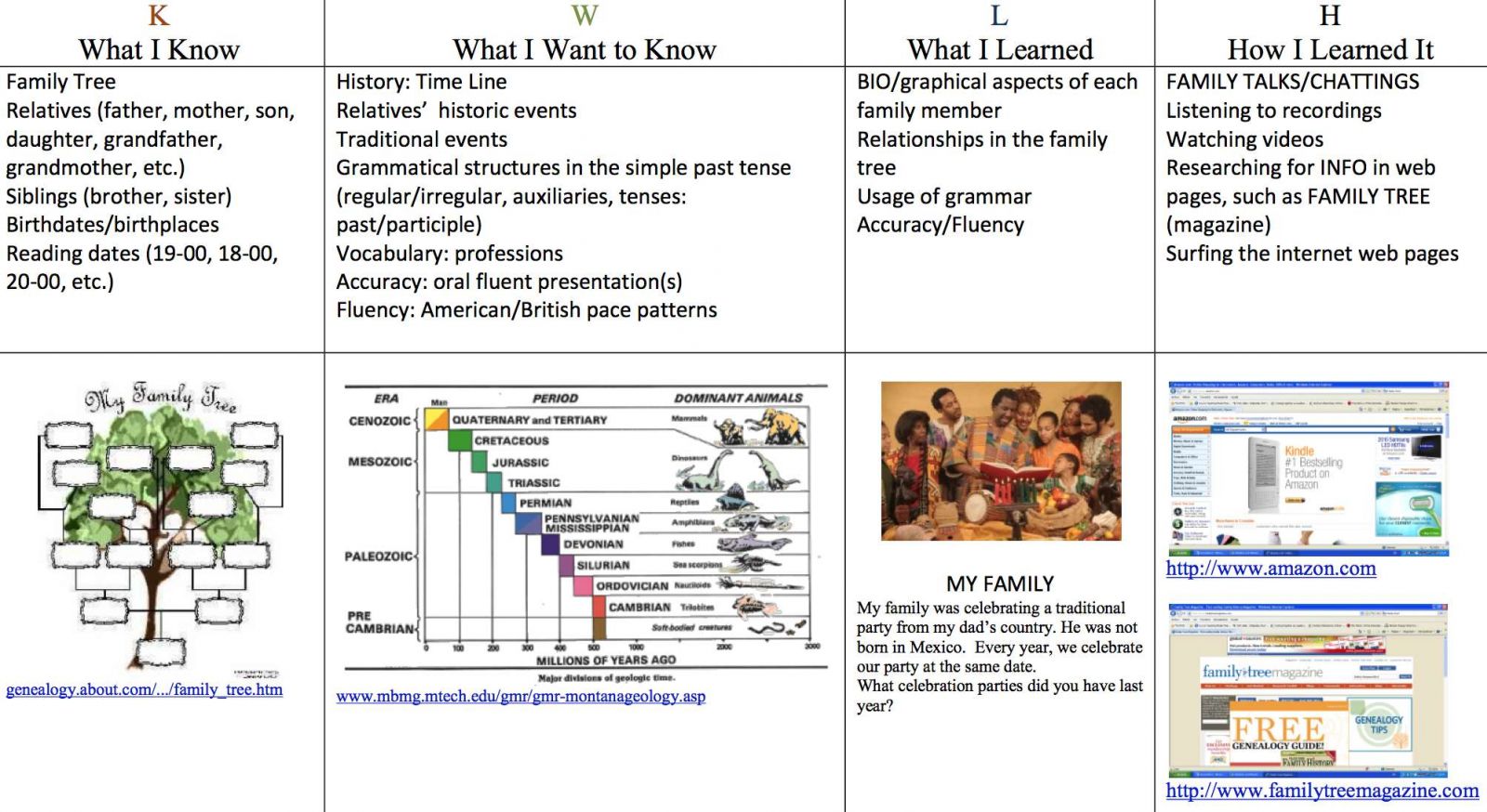

In a learning process, the task will not be finished, if the students´ work is not assessed significantly to complete their learning goals. This means that students have to show that they are competent in the use of such skills (or competencies). One way of doing this, is by compiling the information from the different resources, from a series of steps into a formal presentation. This is, in fact, showing the final product of the task. Students compile their more significant products in the shape of a portfolio. There are different representations of portfolios. The one I am using is a portfolio of evidence. In this kind of portfolio, students take their most significant products (an essay, a PowerPoint presentation, an audio/video recording, a reference from their blog or web page) with a brief description and a comment about how or why this represents an improvement in their work. In this way, the portfolio shows what issues are significant for the students and in what way(s) they are significant. According to Ogle (1986) teachers can use a graphic organizer such as the KWL+ chart to compile such information for the Portfolio of Evidence.

In a KWL+ chart, students record what they have learned and the information which was very interesting to them. In the chart, K stands for What I Know; W stands for What I Want to Know; L stands for What I Learned; and the sign plus (+) stands for How I Learned it. In this sense, each one refers to a step where students acknowledge any kind of information and scaffold it to a previous item or items learned. In the example below, some of the information is related to what the students knew about their families (former information, specifically from the mother tongue) and was linked to other situations or information given.

I can support my teaching and assessment with a variety of tools from the internet such as the webpage Family Tree (www.familytreemagazine.com) which contains information related to the family and family research. The final step in this learning process involves the demonstration of what students learned during the working time. Table 4 shows an example of what students learned during the time they were studying about their family trees. Competencies reflect not only the grammatical items students develop and perform, but also the content of the language(s) involved.

Students demonstrate specific conclusions such as the use of different grammatical, lexical, phonological or semantic aspects involved in the teaching/learning process of the language but they can also show what cultural aspects of the language they have learned and put into practice in the learning process of the language as well. Table 7 shows an example of what students learned during the process of acquiring a second language to describe their family and the issues they encountered in completing the task(s).

Table 7. KWL(H) + Chart (Ogle, 1986)

Conclusion

Students’ skills can be shown in the process of completing a task to develop a required competency. Such tasks can be shown or illustrated by a teacher and assessment expectations can be shown in a rubric or checklist for the student. Teachers should carefully create the checklists to represent each of the expected tasks and accomplishments. They should also show and discuss the rubric with students in order to provide a clear view of what students must do to successfully complete a task and demonstrate mastery of a given competency. Students must learn to do more than memorize and recall but to show some advance thinking skills, for example, higher order thinking skills as outlined by Bloom. With practice students will be able to acquire the skills necessary to achieve mastery.

Tools such as Bloom’s levels of cognitive domain, and the usage of the KWL+ provides ESL/EFL techniques/methods for teachers who want to add new methods for improving learning procedures. A good English teacher is actually one who searches for such techniques/methods to improve not only their own performance and delivery in class, but also helps students improve their competencies. The process of learning and demonstrating competency mastery involves five important steps. First, students must complete a task involving both generic and disciplinary competencies. Next, the tasks created for the students must involve different skills. These would include listening, speaking, reading, and writing, along with higher order thinking skills. Third, graphic organizers should be introduced as a way to show students what they are learning as well as to help them organize materials for successful task completion. Next, carefully constructed rubrics and checklists should be provided by the teacher. These help the teacher to accurately assess competency but they also help to guide the student. Students know exactly what is required for successful completion of a task and all of the components required to do so. Finally, students can provide a portfolio as a way of tracking their most significant work. The portfolio also allows teachers insight into individual student learning processes.

The new communicative English courses in Mexico now require the mastery of competencies across a wide variety of tasks. Students must demonstrate an ability to perform. It is no longer enough to fill in blanks or do scripted activities that may have little relevance outside the classroom. Instead, students need to show that they can actually communicate well enough to perform a real world task. These specialized tasks, examples or demonstrations are the reflection of what she/he has been learning from a communicative course.

References

Bleger, J. (1983). Temas de psicología (entrevista y grupo). Grupos operativos en la enseñanza. Ediciones Nueva Visión, México. pp.57 – 86.

Ferlazzo, L. (2009). Bloom’s Taxonomy [image]. From Doug Belshaw, Flickr, 2009. Retrieved 21 August 2014 from http://larryferlazzo.edublogs.org/2009/05/25/the-best-resources-for-helping-teachers-use-blooms-taxonomy-in-the-classroom

Bloom, B. S. (1956). Taxonomy of educational objectives - Handbook 1: Cognitive domain. London: Longman.

CASAS (2003). CASAS Competencies: Essential Life Skills for Youth and Adults. Retrieved on 21 August 2014 from http://www.learningace.com/doc/2798047/111ce539ddca61b1a54eadc90e38c2fd/casas_comp_list_2003_000.

Centro Virtual Cervantes (1997). Marco común europeo de referencia para las lenguas: aprendizaje, enseñanza, evaluación. Retrieved 21 August 2014 from http://cvc.cervantes.es/ensenanza/biblioteca_ele/marco.

Chomsky, N. (1965). Aspects of the Theory of Syntax. Cambridge, MA: The MIT Press.

COSDAC (2013). Programas de estudio del bachillerato tecnológico: Formación básica y propedéutica. Retrieved 21 August 2014 from http://www.cosdac.sems.gob.mx/programas.php#.

Fromkin, V. & Rodman, R. (1983). An Introduction to Language. New York, NY: Holt Saunders.

Paulikoska-Smith, G. (2000). Canadian Language Benchmarks. English as a Second Language for Adults. Centre for Canadian Language Benchmarks.

Harmer, J. (1987). Teaching and Learning Grammar. London: Longman

Llanas, A. & Williams, L. (2010). Trends I. Mexico: Macmillan.

Ogle, D.M. (1986). K-W-L: A teaching model that develops active reading of expository text. Reading Teacher, 39, 564-570

O’Grady, W., Dobrovolsky, M. & Aronoff, M. (1993). Contemporary Linguistics. An Introduction. New York, NY: St. Martin’s Press.

SCANS (1993). Teaching the SCANS Competencies. The Secretary´s Commission on Achieving Necessary Skills) by the U.S. Department of Labor.

Sosa, E. & Toledo Hermosillo, E. (2004). Reflexiones imprescindibles en el programa de estudios de Ciencia, Tecnología, Sociedad y Valores. SEP/SEIT México Pp. 7 – 16.