Introduction

English as a Lingua Franca (ELF) is used by speakers from different linguistic and cultural backgrounds who do not share a common language (Jenkins, 2009). The complex relationship between ELF and identity makes it worthwhile to conduct further research (Sung, 2014b; 2015). Some previous studies contain inquiries related to identity such as L2 learners’ identity (Gu, 2010; Henry & Goddard, 2015), accent and identities (Ren et al., 2016; Sung, 2013; Sung, 2016), ELF and students’ identities (Baker, 2016; Sung, 2014a; 2014b; 2014c; 2015; Virkkula & Nikula, 2010), EFL and identity construction (Meanard-Warwick et al., 2013; Salinas & Alaya, 2018), identity and positioning (Dagg & Haugaard, 2016; Gu et al., 2014; Søreide, 2006) and lecturers’ subjectivities (Wahyudi, 2018b). However, these previous studies do not address Indonesian EFL learners’ identity constructions as the representation of their subjectivities and their positioning toward English from the ELF context. This gap in the literature requires further investigation.

As an Expanding Circle country (see Kachru, 1990; 2011) with more than 700 local languages (Wahyudi, 2018b), English functions as a foreign language in Indonesia (EFL). However, there has been criticism of Kachru’s theory (Bruthiaux, 2003) stating that the circles only encourage certain varieties of language and seem to ignore the localities, especially when the gap between those who master English and those who do not, is huge. Meanwhile, this theory might contradict the principle of ELF that includes linguistic diversities and use pluricentric approaches (Jenkins, 2002; 2015). Therefore, English use in Indonesia should consider the multilingual and multicultural contexts. The sociocultural conditions make English users in Indonesia multilingual (Wahyudi, 2018b), as is the case for our respondents. It is also relevant to discuss the notion of the multilingual subject proposed by Kramsch (2006) who emphasizes that by focusing on the symbol of a multilingual subject, language learning opens the possibility to construct someone’s multiple identities. In communicating in more than one language, Indonesians tend to have multi-identities and changing subject positions, e.g., from a global to a local identity (Walshaw, 2007).

Theoretical Framework

Addressing the gap, this study aims to explore EFL university students’ identity options seen from Sung’s (2014b) analytical framework of global, local, and glocal identity, as well as Walshaw’s (2007) work on Foucault’s (1980) subject positions and subjectivity, as well as Norton’s (2013) identity theory to enrich the analysis.

Literature Review

There are many scholars, such as Gass (1998), Weedon (1987) and Norton (2013), among others who have studied the issue of identity. Gass (1998) focused on identity research which affects second language acquisition, while Weedon (1987) emphasized the identity constitution through language between the individual and society. In this study, we use Norton’s (2013) notion of identity since this includes identity construction in language learning and the teaching process. We also combine Norton’s (2013) theory of identity with Sung’s (2014b) study of global, local, and glocal identity since Norton’s classification of identity is referred by Sung (2014b).

Identity

Norton (1997) sees identity as the way people understand their relationship to the world, how it is shaped across time and space, and how people understand their future possibilities. Inspired by post-structuralism, this author defines identity as dynamic, contradictory, complex, multifaceted, and implicated in power relationships (Norton, 2000; 2006). Norton (2013) re-conceptualized identity into three points: 1) “Identity as non-unitary and contradictory” (she explains it as diverse, contradictory and dynamic); 2) “Identity as a site of struggle” (the situation when a person might resist the available subject position, or create a counter-discourse to assume a more powerful position); and 3) “Identity as changing over time” (It changes over historical time and social space) (pp. 161-166).

Also inspired by post-structuralist understanding of identity, Sung (2014b) classified three identities in viewing the spread of English: global, local, and glocal identity in Hong Kong (ELF context). The study showed that some L2 learners tend to show their global identity, some of them tend to maintain the local identity, and the rest tend to show both (glocal identity). Zacharias (2012) conducted a study on multilingual English identities of EFL students in Indonesia discovering that the participants’ Multilingual English User (MEU) experiences related to language, culture, and identity regarding their multilingual narratives. The result of the narratives showed that many participants considered their non-native speakers status as their drawback. It led to a suggestion of the inclusion of multilingual narratives in pre-service teacher education as a stepping stone for MEU to recognize issues regarding identity, language, and culture. The current study applies a more complex lens through the incorporation of Foucault’s subject positions, subjectivity (Walshaw, 2007), in addition to Norton’s (2013) identity theory and Sung’s (2014b) study.

Subjectivity and Subject Positions

Danaher et al. (2000) and Walshaw (2007) emphasize Foucault’s subjectivity as the identity of the self as the product of social construction, self-governing, different discourses, ideology, and institutional practices. In the context of EFL learners, institutions may have particular rules that regulate practices where subject positions are set up. As Walshaw (2007) contended, “subject positions are set out for learners and teachers within curriculum policy texts” (p.65). Accordingly, policy is one of the main ways to regulate behaviors and to enhance productivity in the population.

According to Walshaw (2007), the subject position is offered in different discourses since subjective experience is constructed by constantly changing social, cultural conditions, and circumstances. The available subject positions might be accepted, claimed, or resisted by individuals, and subject positions appear and are recognized from particular discourse. The discourse constructs subject positions and the positions offered become available to students. Therefore, regulations achieve their goals if learners decide to identify themselves with the subject positions offered.

In this study, the researchers used curriculum document policies as the ‘written discourse’ to track the participants’ subjectivities and subject positions. Ball (1994) considers curriculum document policy as a way to track someone’s subjectivity. As Walshaw (2007) argues, through discourse analysis, it is possible to interrogate part of the written text of curriculum document, to explain and to comprehend how the policy texts are implemented to the learners. Thus, subjectivity and subject positions are produced and established by the discourse. Foucault (1977) defined discourse as “practices that systematically form the objects of which they speak. Discourses are not about objects; they do not identify objects, they constitute them and in the practice of doing so conceal their own invention” (p. 49). Foucault’s notion of discourse is useful for analyzing the participants’ interviews and university curriculum documents whether or not this discourse relates to their subjectivity construction. It also helps to find the respondents’ tendency of global, local, and glocal identities as the portrayal of their subjectivities

Participants’ subject positions reflect their identities and subjectivities. Identity and subjectivity are two related concepts. In this study, EFL students’ subjectivities and subject positions are investigated to capture EFL learners’ identity concerning Sung (2014b) global, local, or glocal identity.

The History of English in Indonesia

English was first taught in Indonesia in 1914 when junior high schools were created (Lauder, 2008). It became a compulsory subject for the elite along with Dutch (Mistar, 2005). After independence and the establishment of a Republican government on August 17, 1950, the government focused their attention on social and cultural matters including education. Dardjowidjojo (2003a) observed that the choice of English is usually used by newly independent states to create their language policies in bilingual or multilingual societies. Nevertheless, English has never been an official language in Indonesia, but rather coexists with the national language since the British and Americans almost have no political business with Indonesia (Dardjowidjojo, 2003b). Lauder (2008) emphasizes that English in Indonesia could never be widely accepted in daily life, or become the second official language. Rather, it should be “the first foreign language”. It is in line with Dardjowidjojo (2000) that “the status of English as the first foreign language remains today and guides the government in determining policy” (p. 23).

The English curriculum developed beginning with the 1945 curriculum which used the grammar translation approach; in the 1968 curriculum, the oral approach was adopted; the 1975 curriculum, was based on the audio-lingual approach; the 1984 curriculum used a meaning-based curriculum (1994), which ten years later was changed into a competency-based curriculum (2004-2005). Soon after, a school-based curriculum (2006-2012) was adopted including a communicative approach (1984-2012), and, finally, in 2013 a curriculum using religious, productive, and innovative approaches has been used (Wahyudi, 2018b; Widodo, 2016). The grammar translation approach mostly used British textbooks in the teaching and learning process, while the oral approach focused on directly speaking to foreigners. The audio-lingual approach was concerned with receptive skills (reading and listening), and the communicative approach emphasized communicative competence in spoken and written English. The 2013 curriculum has placed the focus on the scientific approach which comprises observing, questioning, exploring, associating, and communicating (Wahyudi, 2018b; Widodo, 2016).

The participants’ previous institutions used a ‘School-Based Curriculum’ or Kurikulum Tingkat Satuan Pendidikan (KTSP) (See Wahyudi, 2018b). School-Based Curriculum is an operational curriculum compiled and implemented in each education unit that adjusts to the region’s specific characteristics, the potential of the region, the education unit, and students (Badan Standar Nasional Pendidikan[1], 2020). It could be used as a reference for the institutions to create the regulation in subjects. Thus, these curricula might have a role in constructing participants' subjectivities when the respondents were exposed to it during their Junior and Senior High School study.

Research Questions

Based on the discussion above, this study is proposed to answer these following questions:

- What are the identities constructed by EFL learners?

- How are EFL learners’ identities constructed in their subject positions in relation to English as a global language?

- How do English as a global language in the curriculum document construct EFL learners’ identities and subjectivities?

Methodology

Participants

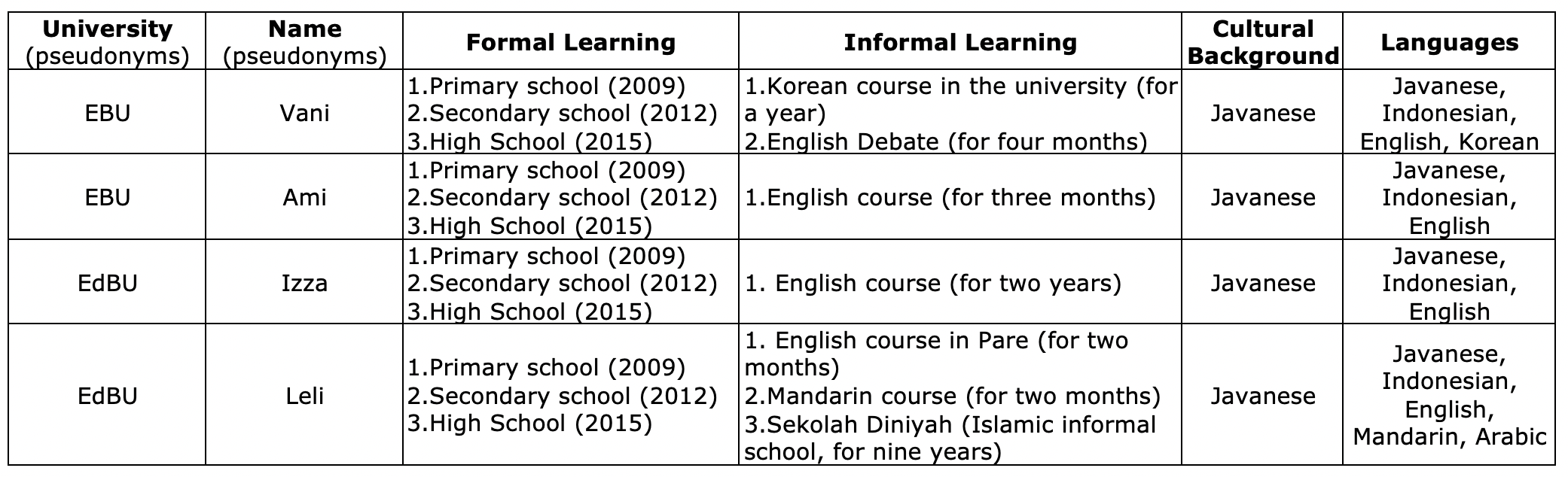

Four participants from two different state universities in Malang, Indonesia, were selected using convenient sampling (Given, 2008). The participants were all women, students in their final year. Vani and Izza (pseudonyms) were English language teaching students, while Ami and Leli were English language and literature students. Their two universities (whose identities have been disguised with pseudonyms) also have different emphasis. The first university emphasizes educational aspects (Educational Based University or EdBU). The second university emphasizes its entrepreneurial aspects (Entrepreneurship Based University or EBU). The English proficiencies of the participants were observed during the interviews. On average they were not very fluent in English and sometimes had difficulties explaining their answers.

Table 1: The participants’ multilingual background

Data Collection

The researchers conducted the semi-structured interviews from April to August, 2019, creating the audio recording, and organizing the curriculum documents as the data collections of this study. The semi-structured interview was used to obtain a deep understanding of the participants’ answers (see Wahyudi, 2018b). The researchers also used observation during the interview to obtain deeper understanding. The observations were made in order to understand participants’ activities in social media, their daily activities, favorite music or movies, as well as the expressions used in answering the questions, and the accents (e.g., British, American, etc.) they used while speaking English. Thus, both interview and observation were used to support the main data and, as Heigham and Croker (2009) emphasize, include multiple data collection methods. During the first stage, the researchers conducted a semi-structured interview with the four learners regarding their background knowledge and understanding of ELF. In the second stage, the researchers interviewed the participants about their identities. The observation of the accents and pronunciations was conducted by asking the participants to do a short exercise related to speaking English to a foreigner to find out their tendency to use a specific accent to help to reveal their identity classification based on Sung (2014b) and Norton (2013). Besides, the researchers also analyzed the curriculum documents of the universities to support the researcher obtaining additional data to reveal learners’ global, local, or glocal identity, subject positions, and subjectivities. Prior knowing participants’ identities, subjectivities and subject positions since it was important to understand the respondents’ past experiences as they are related.

Data analysis

The data analysis was done by looking at key terms in the curriculum policy documents and in the respondents’ interview answers which had already been transcribed (Walshaw, 2007). The transcription was done by listening to the recordings more than three times to ensure accuracy. Following that, we investigated participants’ subject positions based on Sung’s (2014b) global, local, or glocal identity. Then, we discussed the findings in relation to Foucault’s subjectivity and subject position as explained in Walshaw (2007). We also analyzed the data by referring to Norton’s (2013) identity categorizations. The first author consulted with second author, her supervisor (Ribut Wahyudi), to minimize misinterpretation.

Findings

The Analysis of Curriculum Document

Entrepreneurship Based University (EBU) is a university with the status of BLU (Public Service Agency which aims to be the leading university in the country with emphasis on global recognition of science and technology, industrial-based culture, and social welfare). The global recognition here signals the entrepreneur spirit of neoliberal discourse. At the faculty level, the values such as noble character, competences related to language, literary and culture, as well as global competition are accentuated. In addition, national cultures are also given primacy. The words ‘national cultures’ can be interpreted as a collection of local cultures (see Wahyudi, 2018b). It seems the university balances the desire to be part of a global community while still maintaining the locality by inserting national cultures. In other words, the university represents glocal identity (Sung, 2014b) or hybrid identity (Bhabha, 1994).

The second university, EdBU, focuses more on education. This university aims to be the excellent university in terms of science, technology and education. The vision of its departments shows the primary goal of being an Information and Communication Technology (ICT) based university demonstrating global responsiveness on education and English language teaching (ELT). The term ICT-based university reflects the phenomena of globalization in which people nowadays mostly use electronic media. Bunce et al. (2016) emphasize that English is identical with the modernity and progress which have impacted cultures worldwide and are linked with the global economy, media, and internet. It might point out its global identity (Sung, 2014b) since the university tends to show its role in the globalization phenomena.

These analyses reflect Ball’s (1994) argument that curriculum document policy functions as discourse since it exercises power through the production of truth and knowledge and could be used to track subjectivities. Walshaw (2007) emphasizes that discourse analysis can be used to interrogate part of the written text of curriculum document and trace the different discourses which can make up people’s subjectivities. Thus, discourse analysis helps to find out the subjectivity construction of the EBU and EdBU learners through the analysis of the interview to reveal the global, local, or glocal identity.

Interview Findings

It is worth noting that when the interviews were conducted the respondents answered sometimes in English and sometimes in Indonesian. When they responded in Indonesian, the first author (Noor Vatha Nabilla) translated the answers into English.

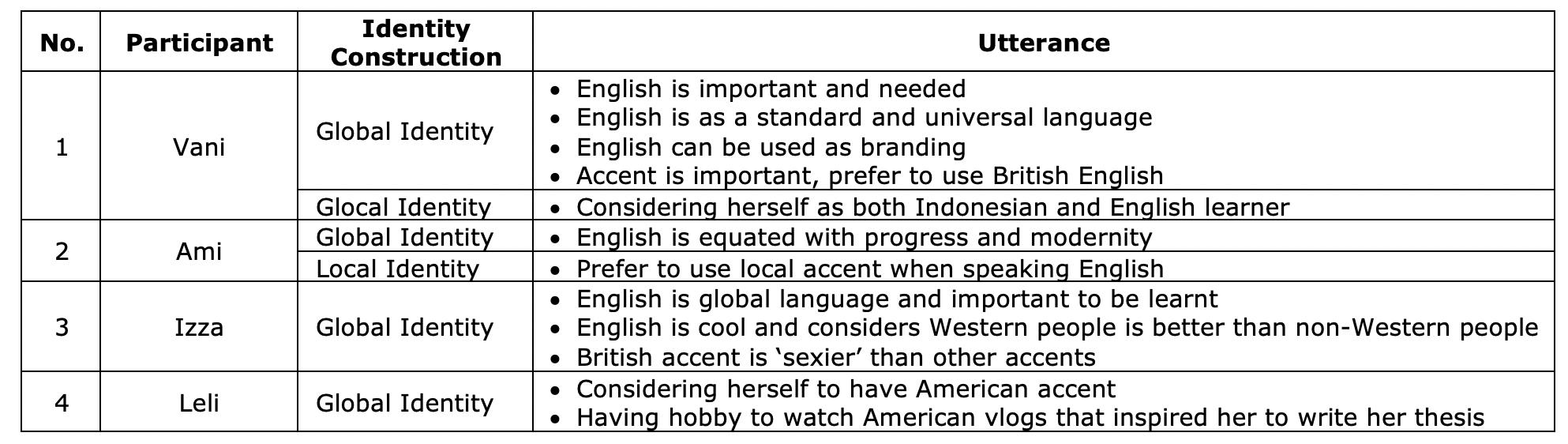

Table 2: The interviews

Participant 1

Vani, a student of English Language Teaching in EBU was asked about her understanding in describing English. She explained that English is important and needed in this globalization era:

[…] Ee (a spoken filler), for me, English is important because as time goes by ee in globalization era, everyone must need English that is already worldwide. It’s like, how I explain it, I confuse how to describe it. (8/4/2019, Initial interview, emphasis added)

The researcher did the follow-up interview to dig up the term ‘globalization’ mentioned by Vani:

Ee about globalization, for me, for me, globalization is a global process. So, it is where one world, ee, become one. So, all access is opened to one world. All countries can communicate to each other, cooperate with each other, like that, connect to each other. […] That's what I think about globalization. And, because English is this, as a standard. Ee, English, a language that, as a language that can be used for communication from all countries. Like, the universal language. (27/6/2019, Follow-up interview)

From that statement, Vani mentioned the words ‘must need’. This phrase indicated that people could not live without English, and it is compulsory to learn. It may reflect the vision of the English Department at EBU to have an international standard in education, research, and community service in English education. Moreover, she also mentioned the word ‘globalization’ and ‘worldwide’ in the initial interview. She elaborated her understanding of globalization by saying the word ‘standard’ and ‘universal’ in the followed-up interview. O’Farrell (2005) explained that Foucault consistently resisted the notion of 'universal' categories which became the source of how people understood the world. The ’universal’ term associates with unchanging or a fixed truth, which might be contradictory with the post-structuralist perspective. Besides, Foucault regarded truth as a historical category (O’Farrel, 2005) meaning that truth is bound to history and therefore, it is not ‘universal’ (Wahyudi, 2018b). Walshaw (2007) emphasizes Foucault’s notion about the ‘truth’ as a social product of its regime of truth and what is considered ‘true’.

Vani’s understanding of English resonates with her department vision written in the curriculum document. The word ‘international’ in the vision of the department related with Vani’s words of ‘globalization’, ‘worldwide’, ‘universal’, and ‘standard’ in “English is important because as time goes by ee in the globalization era, everyone must need English that is already worldwide” and “And, because English is this, as a standard. Ee, English, a language that, as a language that can be used for communication from all countries. Like, the universal language.” In another statement, Vani considered that the ability to speak English could be a ‘branding’:

ee, this is it, I think, using English can be used as branding too. Identically, People who learn English are usually people with more knowledge, like that. They can speak a foreign language, like that. They can speak the global language; everyone in this world knows it. Surely, they have plus points. Well, I consider that is branding. So, if whether we use English in social media, write by using English all the way, the caption is all in English, we have a plus point. We have more knowledge about language. […] The advantage I can get, maybe, I feel proud. […] (27/6/2019, Follow-up interview)

Her statement above indicated that people who can speak English would be seen as quality people. She developed this idea through social media and daily communication, such as writing a caption or inserting English while communicating with her friends. She explained the term ‘branding’ as the image of people who had ‘more knowledge’ and ‘plus point’. Therefore, it evidenced the feeling of ‘pride’ because she could speak English. It indicates that she considers English a prestigious thing and worth being proud of when she could use it well. The feeling of ‘pride’, having ‘more knowledge’ and ‘plus point’ might relate to Bunce et. al. (2016) who said that people wanted to become proficient in English so that they could obtain pride and prestige. The key terms show that the hegemony of English as a ‘prestige’ language had been constructed in her mind.

The tendency of global identity shown by Vani was emphasized with her answer when she was asked about the usage of American, British, or Australian English:

British English is really formal and also the pronunciation is different. I think, it’s okay to make British English as the standard. Americans sometimes pay attention to the grammar, but they have slangs that make them do not care about their grammar. (8/4/2019, Initial interview)

Her statement of ‘it’s okay’ might point out that she admitted English used by American and British as ‘standard’. Vani mentioned American and British English only which might indicate the ‘standard of truth’ for her. Foucault (1980) states “’Truth' is linked in a circular relation with systems of power which produce and sustain it, and to effects of power which it induces and which extend it a 'regime of truth’” (p. 133). However, she mostly uses American pronunciation in the conversation (The transcript of the pronunciation uses the Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary (Oxford University Press, n.d.):

Okay, halo, Tata. My name is Vani /oʊˈkeɪ/ /ˈheɪloʊ/ /tata/. /maɪ/ /neɪm/ /ɪs/ /vani/

Now I’m currently studying in Entrepreneurial Based University /naÊŠ/ /aɪm/ /ˈkÊŒrÉ™ntli/ /ˈstÊŒdi.ɪŋ/ /ɪŋ/ Entrepreneurial Based Universit

I think that’s not right /aɪ/ /θɪŋk/ /ðæt's/ /nÉ’t/ /raɪt/

Although Vani mostly uses American pronunciation, she also uses British pronunciation in some words such as /ˈkʌrəntli/ and /nɒt/. In another data, Vani has explained her thought about the usage of accent:

ee, for me, accent is not so important. The important one is the right pronunciation. […] It is because in our daily life, we use Indonesian and Javanese. It’s different from the native speakers. I prefer to use my accent, local accent. (8/4/2019, Initial interview)

She mentioned that the usage of a certain accent was ‘not so important’. It meant accents did not matter to her. Also, she said that she preferred to use her accent in the last sentence of the data. However, at the same time, she also mentioned ‘the right pronunciation’. It contradicts (see Norton, 2013) when she said accent was ‘not so important’ but ‘the right pronunciation’ was important. People usually checked how to pronounce words in the dictionary where most of dictionaries use American, British, or Australian English. It can be seen in the transcript of her pronunciation that uses American and British English. It shows that the hegemony of American and British English had constructed Vani’s subjectivity in understanding the globalization of English. This finding strengthens the previous study conducted by Wahyudi, (2018b).

Vani mentioned that British English is more formal than American English which has a lot of slang. American English also has formal and informal language. She argued that “it’s okay to make British English as the standard and American sometimes pay attention to the grammar, but they have slangs [sic] that make them do not care with [sic] their grammar” which seems to indicate that she prefers British English more indirectly. However, the transcript above shows that Vani mostly uses American English and less British English. It might show that it is hard to have only one variety of English as she was exposed to different varieties in different contexts such as her exposure to English debate and her hobby listening to songs. She explained that she had taken a debate course in her university for two months and learned American and British styles:

I had joined debate for two months. [...] So I had learnt two kinds of debate style which are American and British styles. (8/4/2019, Initial interview)

Moreover, she likes listening Ariana Grande, Paramore, and Dua Lipa songs:

I usually listen to Ariana, Paramore, and Dua Lipa. (8/4/2019, Initial interview)

She listened to different singer nationalities such as Ariana Grande and Paramore (from the US) while Dua Lipa is British. These exposures constructed her use of different varieties of English. This part of the analysis suggests that Vani tends to have a global identity, which shows her desire to be part of a global (Sung, 2014b).

In the same interview session, Vani also showed different identities when asked whether she would accentuate her status as Indonesian who can speak English or as an English learner globally:

For me, I can be both, I’m Indonesian and also English learner. Perhaps, I will introduce my culture to them, but I will still learn English there. (8/4/2019, Initial interview)

In this statement, Vani explained that she would emphasize both as Indonesian and also a global English learner. She tended to show her glocal identity in this part of the interview. This subjectivity might relate to her department rule that required that every Thursday be English Day. The students must speak English in their faculty area using terms such as canteen, class, and toilet among others. On English day, they also must wear Batik (the National costume of Indonesia, originating with the Javanese tribe):

In my department, every Thursday is English day. All of English Language Teaching students must use English even though they are on canteen or everywhere in my faculty area, they must use English. […] So, in English day, English Language Education students must speak English and also wear Batik. It’s as a balancer, although we speak in English but we still maintain our culture. (8/4/2019, Initial interview)

In the last sentence, Vani explained that although it is an ‘English day’, the students must wear Batik ‘as the ‘balancer’. The combination of wearing Batik while speaking in English might indicate that her department regulation supported her to foreground glocal identity that blended the local culture and global activity (Sung, 2014b). This analysis is categorized as ‘identity as multiple and contradictory’ and ‘identity as shifting across the time’ (Norton, 2013). Vani seems to change her identity from global to glocal identity and tends to have more than one identity. Norton (2013) has argued that if identity is not a fixed category, non-unitary, changing over time, and is a site of struggle. Moreover, her statement about ‘correct structure’ and ‘right pronunciation’ when speaking English (showing her global identity) is opposed to 'English day' activity. Wearing batik suggests local culture and global activity (speaking dominant English) in the ‘English day’ (showing her glocal identity). Furthermore, the shifting of Vani’s identities from global to glocal identity shows that identity shifts across time (Norton, 2013).

Vani explained that every student who speaks other languages instead of English would be fined by paying five hundred rupiahs each word:

The dean has signed the regulation. Every student who do not obey they rule, in the old regulation when I was still active in the campus, students must pay five hundred rupiahs each word. The money will be given to the assemblage. [...] (8/4/2019, Initial interview)

Walshaw (2007) emphasized it as a discipline and punishment method. The fine must be paid as a form of punishment so that the students could be disciplined. Grant (1997) argues that “Students are the subject to the institution regulations which understand the meaning of being a 'good' student from their 'conscience'” (p.110). This is in line with Walshaw (2007) that policy is one of the main ways to regulate behavior.

Vani also mentioned “in the old regulation when I was still active in the campus [sic]”, meaning that she had participated in English day many times. It suggested that the regulation of the department also had partly constructed her subjectivities. This analysis matched that of Danaher et al. (2000) and Walshaw (2007) which emphasized Foucault’s notion of subjectivity to explain oneself as the product of social construction, self-governing, and institutional practices. Moreover, Vani also shows the shifting of her subject position by changing her identity from global to glocal identity. The changing to glocal identity seems to be happening because of the regulation of the department. It might be in line with Walshaw (2007) who states subject positions emerge and are constructed from particular discourses and as the bearers of power or knowledge.

Participant 2

The second participant is Ami, a student from English Language and Literature at EBU. The researcher asked the same question about her understanding of describing English:

Ee, my opinion about English is, ee, important. If, actually in Indonesia, English is not a second language but foreign language. So, it is not an urgent thing to be learnt. […] (15/4/2019, Initial interview)

In this part, Ami seemed to be unsure when she explained the importance of English. It could be seen from the repetition of saying ‘ee’. It might indicate that she was thinking, rethinking, or hesitating. However, she did the opposite behavior when she explained that ‘English is important’. At the same time, she also said English was not an urgent thing to be learnt for Indonesians. It might indicate that there was a contradictory thought in her understanding of English. It is in line with post-structural thinking that is dynamic and contradictory (Grbich, 2004, Norton, 2013). Moreover, it contrasts with her status as an English student. The researchers then asked her to explain why she took English major study while she mentioned that ‘English is not an urgent thing to be learnt’:

Because nowadays, technology and everything is increasingly developing. Automatically, human resources also must develop, and one of them is by learning English. […] It is not difficult to learn English anywhere and anytime because it is easy to be obtained from the internet or books. […] (20/8/2019, Follow-up interview)

Ami’s statement above explains that human resources must ‘develop’ by ‘learning English’ that can be learnt from the ‘internet’. This point might indicate that she becomes consistent with her statement ‘English is important’ since she explained the importance of learning English to use technology and access the internet. Those key terms implicitly could indicate that she relates ‘learning English’ is as ‘progress’ to ‘develop’ human resources. She also mentioned that ‘the internet or books’ are one way to learn English easily and the word ‘technology’ might represent modernity. As Bunce et al. (2016) argue, English is equated with modernity and progress as it is linked to the media and the internet in the global context. Relating to Sung (2014b), Ami tends to show her global identity as part of a global world in this analysis.

Ami’s understanding about ‘English is international language’ is shared below:

ee I think English is used to ee, the formal thing, for example, there are countries, between countries, what is it, bilateral relations or international relations; usually, they use English. [...] Well, that's what I mean by international language which the international community recognizes for us to communicate between countries even though they might use, their own language. But it is still translated into, the interpreter translates it into English. (28/6/2019, Follow-up interview)

Ami had mentioned that English is used to communicate in ‘international relations’ which means that there are many countries with different languages. Indirectly, she had explained the English use as Lingua Franca. Cogo (2012) and Sung (2014b) state that ELF is a contact language used by speakers with a different linguistic and cultural background who do not share a common first language. It might indicate that the status of the students as ELF users is used to fulfill the desire to be a globally recognized university. It points out that the subject position can be seen in the construction of the institutional basis of discourses constructed in texts (Walshaw, 2007).

Another part of the interview found out Ami’s tendency to identity. The question was about the usage of American, British, or Australian accent. Ami also emphasized that the accent is not so important. She explained that her view on accent was constituted when she heard her speaking lecturer did not use American, British, or Australian accent but local accent:

It’s not American or Australian accent, but it’s Indonesia. So, it’s like ‘medhok’ (Javanese accent). (15/4/2019, Initial interview)

Then, the researchers asked Ami about the impact on her when she found out that her lecture was not concerned about certain accents:

I realized that actually lecture does not too concern with the accent. The important thing is that communication can run well. It doesn’t matter with the accent. It seems like someone has said it. We are as Indonesian, if they want to follow a certain accent, it’s their preference whether they want to use American or Australian accent, but it’s not a necessity. The important one is communication can run well. That’s it. It seems someone has said it but I forgot. (15/4/2019, Initial interview)

In the initial interview, Ami only mentioned two varieties of English: American and Australian accents. It might be as the department only provides American Studies and Australian Studies courses that makes her only refer to those two English varieties. Moreover, her answer about the usage of the local accent indicated that she emphasized local identity (Sung, 2014b). It could be seen when she said, ‘it doesn’t matter with the accent’ and ‘it’s not a necessity’ because English in Indonesia is a foreign language, not a second language.

It also reflected the definition of Expanding Circle by Kachru (1990) and Darjowidjojo (2003) that English could never be widely used in daily life, or become the second official language. Still, rather it should be “the first foreign language”. It is an attempt to protect the local languages and cultures of Indonesia and maintain its identities. This analysis has indicated that Amy shows two identities (global and local) which resonates Norton’s (2013) reconceptualization of identity: 1) contradictory and multiple, and 2) changing from time to time. It is multiple identities since Amy shows two identities; global and local. Also, the changing identity from global to local might indicate that identity changes from time to time (Norton, 2013).

Prior to meeting her speaking instructor (lecturer), Ami was concerned with the accent (American, British, or Australian) as seen below:

I realized that actually lecturer does not too concern with accent. […] (15/4/2019, Initial interview)

The researcher asked her reaction after finding out that her speaking lecturer did not concern with the accent:

The impact is (about her lecturer who does not concern in accent) I also don't care too much about accents that mean you have to use a British American accent or an Australian accent. The important thing is it is clear, and maybe, I’m more concern about the stressed and unstressed part (28/6/2019, Follow-up interview)

After she found out that her speaking instructor used a local accent, she also considered that certain accent was not so important. Devine (2003) emphasized that the teacher is the active agent to construct the students’ identities or subjectivities. Wahyudi (2018b) has revealed that the lecturer’s subjectivities have contributed to student’s subjectivity formation. It might indicate that her subjectivities mostly were created from the self-governing, different discourses, and institutional practice (Walshaw, 2007). In this part, Ami points out the shifting of subject position from global to local identity. Her lecturer has a role in her construction of local identity since her lecturer does not match a certain accent when she speaks in English. This situation might correspond with Walshaw’s (2007) explanation that subject positions emerge and are constructed from particular discourses.

In the follow-up interview related to the use of accents, she still mentioned that she is more concerned about the ‘stressed and unstressed’ part. The ‘stressed and unstressed’ of a word is seen from the dictionary, whether it is American, British, or Australian dictionary. It seems to show that she still uses Inner Circle English varieties as the references (Kachru, 1990). It means that Inner Circle English varieties still hegemonize the countries in which the status of English is as a foreign language (see Wahyudi, 2018b).

Participant 3

Izza was a student of the ELT department at EdBU. When the researchers asked her about understanding of English, she explained that English was very important and it was a basic thing to be learned by young learners:

Ee, it is very important, emm, because, ee English is a global language now, ee, to, emm, a language as connector between ee a human with another human, [...] it starts to be learnt as early as possible because it is very important, so that emm so that we are as prospective, prospective educators must learn it deeper because emm because ee most of young learners or teenager nowadays already use English ee as the most basic thing. [...] (8/4/2019, Initial interview)

The researchers tried to delve deeper into her understanding of ‘English as a global language’:

The global language used by all of us now is English. We have seen from the colonial era that English controlled almost all of the world. Ee, then British colonized America, which now America is as a big country. America is strong that makes other countries dependent on America. […] Well, ee because the countries in the world need help from America, so inevitably, all those countries must be able to speak English. […] A strong country means that the country used as the reference, such as technologies. It also comes from there. (2/7/2019, Follow-up interview)

By mentioning ‘English is a global language’, it indicated that English’s hegemony had created her understanding of the language. Izza still has a thought that America and Britain dominate among others. In the follow-up interview, she gave an example of America as the reference of ‘technology’ in the sentence “A strong country means that the country used as the reference, such as technologies.”

The word ‘technology’ is actually in accordance with EdBU vision and also the ELT department’s vision. This might emphasize that the university focuses on the use of ‘technology’ as a response to the ‘global advancements’ in educational matters. It also seems to indicate that EdBU tends to emphasize its global identity at this point. The university may have a sense of being part of global so that it tends to show its global identity (Sung, 2014b).

The discourse ‘English as a global language’ above had created pride in her. Izza mentioned that English was ‘cool’ and explained in detail that the Westerns who use English as their language are more than the people who do not speak English:

It is cool because nowadays we are required to be able to speak English. [...] Well, and we see the outside world (Western) is more than us, the people are more than us. [...] English will make it easier for you to interact with foreign people who are better than us.

In the excerpt above, Izza stated that ‘(Western) is more than us, the people are more than us’ and ‘foreign people who are better than us’. In this context, ‘Western’ and ‘foreign people’ represent the people who use English as their daily communication or native speakers. Those statements by Izza might indicate that she is ‘Western-minded’ since she argued that they are more than us (Indonesian or non-native). The discourse of English domination has hegemonized her. KarakaÅŸ (2019) emphasized that the use of certain accent works beneath the hegemonic ideologies and from the doctrines of prevailing ideologies. She might also assume that the ‘privilege’ given to the dominant language could give a ‘higher’ status. Phillipson (1992) states that this phenomenon is called as ‘English linguistic imperialism’. It discussed the domination of English internationally, which maintains continuous reconstruction of structural and cultural inequalities between English and other languages (Phillipson, 1992; Phillipson & Skutnabb-Kangas, 2013).

Talking about accents, Izza admitted that she wanted to have a British accent:

In fact, I want to use the British accent. I don’t know. I think that’s sexier. [...] But, we study English since in Junior or Senior High School. It makes us use our own accent. So, it’s difficult for us to speak like a native speaker. But, I truly attempt to how I can speak like a native speaker. (8/4/2019, Initial interview)

It could be seen in the spoken English exercise (The transcript of the pronunciation uses Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary (Oxford University Press, n.d.):

I think that’s more sexy /aɪ/ /θɪŋk/ /ðæt's/ /mÉ”Ër/ /ˈseksi/

I think that how they speak /aɪ/ /θɪŋk/ /ðæt/ /haÊŠ/ /ðeɪ/ /spiËk/

Indonesia has five big island /ˌɪndəˈniËÊ’É™/ /hæz/ /faɪv/ /bɪɡ/ /ˈaɪlÉ™nd/

The transcript of the pronunciation from the interview shows that Izza uses American English even though she wants to speak British English. However, based on the researcher's observation, she attempted to use British accent in spelling the words ‘sexy’, ‘that’, ‘speak’, and ‘five-big island’ although it was not the same. Foucault (1997) names it as ‘disciplining of oneself’, which means “allowing the self or others to operate their conducts, thoughts, and way of behaving to be changed in aims to obtain certain state of happiness, purity, wisdom, and perfection” (p. 225). By ‘attempting’ to be native-like even though it is ‘difficult to speak like native speaker’, Izza just has ‘operated’ her ‘thoughts, conduct, and way of being’ to be like a native speaker. This technology of the self also might be the production or the extension of one’s subjectivity (Harwood, 2006; Wahyudi, 2018b). Moreover, Izza explained that her attempts to have a British accent was related to watching movies and listening to music and that these already had become her hobby:

[…] I started it from Harry Potter. This movie is so British. I started from that movie. So, I realized that American and British accent are different. When I started to speak English a little bit fluently and most people use American accent, I found out an accent cooler than that. Finally, I try to put in British accent when I speak English. […] Every day, I listen to music. I like Adele, Avril, Coldplay, Queen, and many more. (8/4/2019, Initial interview)

Knowing her hobbies and other efforts indicated that she really wanted to imitate how the British were speaking. In this part of the interview, she emphasized her global identity because she tried to speak like one of the Inner Circle Countries English (Sung, 2014b). By admitting that Izza ‘attempts’ to have ‘British accent’ since it is ‘sexier’ than other accents, it means she tends to show her global identity as an EFL learner by having the desire to be native-like. As Sung (2014b) states that global identity indicates that someone wants to be part of a global world. It also matches Norton (2013) and Bucholtz and Hall (2005) in that identity is closely related to how people understand their relationship to the world and how they are constructed across time and space as in social interaction with other people. At the same time, it also proves that revealing someone’s subjectivity also reflects the tendency of identity (Danaher et al., 2000; Walshaw, 2007).

Participant 4

The last participant is Leli, a student of the ELL department at EdBU. She was also asked about her understanding and description of English as the first question. She stated that:

In my opinion, English is a foreign language, but, it has been no longer as a foreign language to anyone, people in the world, including in Indonesia. It is indeed a foreign language, but from the young kids, they can speak English, even though it is not their mother tongue. (25/4/2019, Initial interview)

The researchers asked Leli to give an example about her statement that although ‘English is a foreign language, it has been no longer as a foreign language for anyone’:

Even though English is a foreign language, but, in our life, English is actually no longer a foreign language. For example, in some restaurants or cafes, the menus are written in English. [...] Nowadays, if there are western songs, Junior High School, Senior High School, and even Primary School students enjoy the song even though they don't understand the meaning. And also in Indonesia, vlogs spread very widely. The Indonesian vloggers also often use mixed language (Indonesian and English). Moreover, on YouTube, children can also see vlogs from other English-speaking countries. (28/7/2019, Follow-up interview)

In the excerpts above, Leli stated, “English is a foreign language, but, it has been no longer as a foreign language” twice in the initial interview and follow-up interview. She argues that since English is widely used in restaurants’ menus and vlogs, it is no longer a foreign language. Her statement contradicts Lauder’s (2008) argument that states the status of English in Indonesia could never be widely used in daily life, or become the second official language. Rather, it should be “the first foreign language”. It contradicts facts since Indonesian L1 is mostly the local language and the L2 is Bahasa Indonesia. However, Leli explained that “English is not a foreign language anymore” since English nowadays has been used in public places such as restaurants, cafes, and used by many (privileged) Indonesians. However, the status has not changed to not being a foreign language since there has not been a policy yet to change the status and also due to the fact that English is not used in daily communication in most contexts. Dardjowidjojo (2000) emphasized that English became the first foreign language in Indonesia after independence until today.

Another statement is that vlogs are widely spread in Indonesia, whether the vloggers are from Indonesia or Western countries. However, she mentioned that although the vloggers are Indonesian, they often mix their language (Indonesian and English). Moreover, watching vlogs also becomes Leli’s hobby. She explained that she often watches a food vlogger from America:

I don’t really listen to music, it's more like watching at vlogs. [...] I often see American vlogs about food or beauty vlogger. […]And it's inspired me to write my thesis, it is about vlogs. It is Grice's cooperative principle, conversational maxim. So, I analyzed it. Then, I differentiate between American and Indonesian vlogger. [...] (25/4/2019, Initial interview)

Leli’s statements about ‘song’, ‘vlog’, and even used ‘vlog’ as the data for her thesis, are actually related to media and technology. Moreover, she mostly uses media and technology related to the use of English too, for example, ‘Western songs’ and ‘American vloggers’. The use of vlogs as her research reflects the supporting competencies point of her department policy which states that the alumni of undergraduate students of the ELL department should be able to use ICT-based research in their studies of literature and language.

Leli has integrated and employed ICT-based (the vlogs) to the field of ELL by analyzing the conversation using Grice's cooperative principle along with the conversational maxims, as Walshaw (2007) states that “Subject positions are set out for learners and teachers within curriculum policy texts” (p.65). It appeared that Lely occupied the subject position offered by the university.

Related to America, Leli also mentioned that she tended to have an American accent. The researchers asked whether or not she used an American, British, or Australian accent while speaking in English. She said that:

I don't choose one of them. But, I think 'my tongue' is more into American (accent). It’s because I can listen more to people with an American accent. It is hard to understand people who speak with a British accent. (25/4/2019, Initial interview)

As Leli said that she had an American accent, the researchers asked her to speak in English (The transcript of the pronunciation uses Oxford Advanced Learner’s Dictionary (Oxford University Press, n.d.):

I come to Malang for college by bus or train /aɪ/ /kÊŒm/ /tu/ /MalaÅ‹/ /fÉ”Ër/ /ˈkÉ’lɪdÊ’/ /baɪ/ /bÊŒs/ /É”Ër/ /treɪn/

It will take three to four hours /ɪt/ /wɪl/ /teɪk/ /θriË/ /tu/ /fÉ”Ër/ /ˈaÊŠÉ™rs/

We are surrounded by our relatives /wi/ /É‘Ër/ /səˈraÊŠnded/ /baɪ/ /ˈaÊŠÉ™r/ /ˈrelÉ™tɪvs/

In the excerpts above, Leli admitted that she is more into an American accent. She also emphasized that she could hear people with an American accent better than the British accent. It might be caused by watching American vlogs rather than vlogs from other countries. It could be seen from the transcript of the pronunciation such as /fÉ”Ër/, /É”Ër/, /É‘Ër/, and /ˈaÊŠÉ™r/. American English emphasized the sound ‘/r/’ at the end of the words. However, she still uses British pronunciation in the word ‘college’ (/ˈkÉ’lɪdÊ’/). It might show that it is hard to claim to have just one variety of English.

The analysis of pronunciation has shown that she still uses British English, although she said that it is not familiar for her. Furthermore, it seems to indicate that the hegemony of American and British English ‘unconsciously’ has become a ‘pleasure’ for her since she said she ‘did no efforts [sic]’. However, the facts show that she has American English pronunciation and accent, and she always watches American vloggers. In this part, Leli tended to have a global identity because she shows the desire for being part of a global community (Sung, 2014b) by admitting that she has an American accent. Also, her global identity could be seen by her daily activity that mostly watched American vlogs used for her thesis topic, which made her became ‘American English-centered’.

Sung (2019) also argues that constructing one’s identity relates to specific contexts and is mediated by the possibility ofestablishing a good return on the investments. In the interview, she admitted that her habit of watching American vlogs had inspired her to write her thesis project in the statement of ‘It's (American vlogs) inspired me to write my thesis, it is about vlogs’. Here, Leli’s activities on the media related to the use of American English has contributed to constructing her identity to be ‘American English-centered’ which she might consider has given a ‘good investment’ to her thesis project which discusses American vlogs. It is in line with Norton and Gao’s (2008) statement that the learners seem to look on the investment as symbolic and material sources in a broader space which is possible to increase the value of their cultural capital. Leli’s activities regarding media, technology, the use of English while using it, until using vlogs for her thesis project might reflect the ELL department’s vision and mission which aim to promote ICT-based learning through global development and engagement.

Discussion

In this study, global identity (Sung, 2014b) is shown by the four participants supporting a previous study by Menard-Warwick et al. (2013) about how participants oriented to global contexts in an EFL Internet Chat Exchange. It also supports Gao et al. (2016) about participants’ construction of multiple kinds of global identities in their involvement with ELF. However, those previous studies used different theories to analyze the global identity of the participants. This study employs Norton’s (2013) identity theory and Sung’s (2014) study. Although the methods they used were different: we used semi-structured interviews. Moreover, those previous studies focused on politics and educational issues from global perspectives through the Internet Chat Exchange and participants’ participation in business practices. This study emphasized EFL learners’ activities in their institutions and its role in constructing learners’ identities and subjectivities.

Also, one of the factors to have a global identity is the desire to use a certain accent of the Inner Circle English as shown by Izza and Leli. It is in agreement with Sung (2013), Ren et al. (2016), and Sung (2016) whose findings show that through the use of an accent, it is possible to construct someone’s identity. Previous studies investigated L2 learners who were bilingual speakers, however, this study involved multilingual EFL learners. The different participant’s background language might provide different analysis of how their identities were constructed since their culture, society, and living background were also different. Moreover, this study’s findings show that their tendency of global identity might be constructed from the subject position of their institution, which also reveals participants’ subjectivities (see Danaher et al., 2000; and Walshaw, 2007).

In contrast, Izza has the desire to have a British accent by practicing and imitating native speakers, listening to British songs, and watching British movies. Those activities are in line with the notion of technology of the self (see Foucault, 1997) that contributes to the construction of her global identity. She also admits that the British accent is ‘sexier’ than the others. Leli feels she could have an American accent since her habit is watching American vlogs in daily life. It might construct her identity to be ‘American English-centered’ and consider that American vlogs could become a ‘good investment’ for her thesis project topic (Norton and Gao, 2008; Sung 2019). In addition, Vani shows her global identity since she assumes that the ability to speak English could give her ‘branding’ which shows her as a person who has ‘more knowledge’ and get ‘plus point’ from the environment. Ami expresses her global identity by relating English as a ‘progress’ to ‘develop’ human resources since English is an international language that nowadays could be learnt everywhere from the internet. This might indicate that she equates English as ‘progress’ and ‘modernity’ (Bunce et. al., 2016). However, previous studies do not provide any other specific factors that might be possible to construct participants’ global identity.

The tendency of local identity (Sung, 2014b) is only revealed on Ami’s identity. The use of certain accent in the previous discussion shows Izza’s and Leli’s global identity, yet Ami decides to maintain her local accent while communicating in English. This finding seems to resonate Sung’s (2014c) study about how the participants expressed the importance of maintaining their cultural identities as Hong Kong or Chinese speakers of EFL contexts. The role of local accent in the construction of Amy’s local identity might also be in line with Sung (2013), Ren et al. (2016), and Sung (2016). Previous studies revealed that participants’ local identity was mostly constructed by the desire to maintain their sociocultural identity as Hong Kong and Chinese people. They are concerned that local accents are related to the perceived relationship between accent and identity. However, a lecturer’s subjectivity plays a role in Ami’s construction of local identity. The findings show that Ami’s local identity is constructed since her lecturer prefers to use local accents while teaching. As Devine (2003) said a lecturer is an active agent to construct the students’ identity or subjectivity. Wahyudi, (2018b) argued that lecturers contribute to shaping students’ subjectivities.

Finally, glocal identity (Sung, 2014b) was only reflected in Vani. In the findings, Vani admits that she could be both an Indonesian and an English learner at the same time, which is in line with Henry and Goddard’s (2015) findings about the emerging of hybrid identity. The findings showed that the participants constructed glocal identity from participating in identity-defining youth cultural practices that used English and had a transnational contact network. Vani’s construction of glocal identity has been triggered by the department’s regulation of ‘English Day’ practice to speak English while wearing Batik at the same time. It is a form of blending global practice and local culture. The construction of Vani’s glocal identity is integrated to the subject position available constituted by the department (see Walshaw, 2007). The curriculum document analysis also supports Ball’s (1994) statement that discourse exercises power through the production of truth and knowledge.

Conclusion

This study has indicated each EFL participants’ global, local, or glocal identities (Sung, 2014b). Two of the participants have shown different identities. Vani tends to have global and glocal identities concurrently indexing her university background. ‘The ability to speak English as branding’ and ‘using the right pronunciation’ might point out her global identity. Moreover, the department regulation about ‘wearing Batik in English day’ seems to reflect Vani’s desire to be both ‘as Indonesian and as English learner’ which shows her tendency to a glocal identity. Besides, Ami shows her local and global identity in the finding. ‘English is equated to progress and modernity’ (Bunce et. al., 2016) seems to point out her global identity. Furthermore, she did prioritize the certain Inner Circle as inspired by her teacher. This local accent suggests her local identity. Izza tends to show a global identity since she directly admitted that she wanted to have a British accent. She states that the British accent is ‘sexier’ than other accents. Furthermore, Leli has shown global identity in the findings by admitting that she tends to have an American accent. Besides, American English seems to be her part of daily activity since she usually watches American vlogs. The results seemed to be in line with the critics of Kachru (1990; 2011) about the classification of English circles since the circles show linguistic diversities and use pluricentric approaches (Jenkins, 2002; Jenkins, 2015). This could be indicated by the different aspects of each participant in their global identity.

The different aspects of global, local, and global identities as well as the construction of each participant might be partly connected to their exposures in their previous institutions, e.g., schools. All of their previous schools used a school-based curriculum that made the institutions had a chance to adjust the learning materials based on region’s specific characteristics and potential aspects. This kind of curriculum emphasized developing communicative competence (speaking and writing). Speaking and writing materials given by the institution might still use American or British standards as the benchmark since the institutions offered practical activities such as having an English course in Pare for two weeks and an English course for TOEFL test preparation. Moreover, the informal learning done by the participants such as joining another language course, daily life activities, hobbies (e.g listening to American or British musicians and watching American or British movies/vlogs) might partly have a role in constructing participants’ identities and subjectivities. However, the identities shown by the participants are not fixed and changeable based on time and space (Norton, 2013). Also, the participants who only show their global identity might not always indicate that their identities are unitary. The situation, time, and the other aspects at the time when the researcher collected the data might constraint respondents’ choices of identity options.

The University regulations, visions, and missions along with constituted subject positions in the students’ code of conduct might partly construct students’ subjectivities. The vision and mission of EBU which still maintain locality seem to be embedded in Vani and Amy’s subject position to have glocal and local identities besides their global identity. Moreover, EdBU vision and mission emphasize the ‘international standard’ which might shape Izza’s and Leli’s global identity. Therefore, the participants’ identities seem to be constructed by many factors such as the use of the background of the study, former schooling including curriculum, hobbies, daily life activities, and university regulations. All these factors contribute to students’ subject positions towards global, glocal and or local identities.

Acknowledgement

This article is a summary of Noor Vatha Nabilla’s unpublished undergraduate thesis.

References

Badan Standar Nasional Pendidikan. (2020). Panduan Penyusunan Kurikulum Tingkat Satuan Pendidikan Jenjang Pendidikan Dasar dan Menengah [Guidelines for primary and secondary education curriculum design]. https://bsnp-indonesia.org/tentang-bsnp-2

Ball, S. J. (1994). Education reform: A critical and post-structural approach. Open University Press.

Baker, W. (2016). Identity and interculturality through English as a lingua franca. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 26(2), 340–347. https://doi.org/10.1075/japc.26.2.09bak

Bruthiaux, P. (2003). Squaring the circles: Issues in modeling English worldwide. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 13(2), 159–178. https://doi.org/10.1111/1473-4192.00042

Bucholtz, M., & Hall, K. (2005). Identity and interaction: A sociocultural linguistic approach. Discourse Studies, 7(4-5), 585-614. https://doi.org/10.1177%2F1461445605054407

Bunce, P., Phillipson, R., Rapatahana, V., & Tupas, R. (Eds.) (2016). Why English? Confronting the Hydra. Multilingual Matters.

Cogo, A. (2012). English as a Lingua Franca: Concepts, use, and implications. ELT Journal, 66(1), 97–105. https://doi.org/10.1093/elt/ccr069

Dagg, J., & Haugaard, M. (2016). The performance of subject positions, power, and identity: A case of refugee recognition. European Journal of Cultural and Political Sociology, 3(4), 392-425. https://doi.org/10.1080/23254823.2016.1202524

Danaher, G., Schirato, T, & Webb, J. (2000). Understanding Foucault” A critical introduction. SAGE.

Dardjowidjojo, S. (2000). English teaching in Indonesia. In Sukamto, K. E. (Ed.), Rampai bahasa, pendidikan dan budaya: Kumpulan esai Soenjono Dardjowidjojo (pp. 83-91). Yayasan Obor Indonesia.

Dardjowidjojo, S. (2003a). The role of English in Indonesia: A dilemma. In Sukamto, K. E. (Ed.), Rampai bahasa, pendidikan dan budaya: Kumpulan esai Soenjono Dardjowidjojo (pp. 41-50). Yayasan Obor Indonesia.

Dardjowidjojo, S. (2003b). The socio-political aspects of English in Indonesia: A dilemma. In Sukamto, K. E. (Ed.), Rampai bahasa, pendidikan dan budaya: Kumpulan Esai Soenjono Dardjowidjojo (pp. 51-62). Yayasan Obor Indonesia.

Devine, N. (2003). Pedagogy and subjectivity: Creating our own students. Waikato Journal of Education, 9, 29-37. https://doi.org/10.15663/wje.v9i0.383

Foucault, M. (1977). The archaeology of knowledge. Tavistock.

Foucault, M. (1980). Truth and power. In C. Gordon (Ed). Power/knowledge: Selected interviews and other writings, 1972-1977. (pp. 109-133). Pantheon Books.

Foucault, M. (1997). Technology of the self. In P. Rabinow, (Ed.). Ethics: Essential works of Michel Foucault (1954-1984) (pp. 223-251). Penguin Books.

Gao, Y., Ma, X., & Wang, X. (2016). Global and national identity construction in ELF: A longitudinal case study on four Chinese students. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 26(2), 260–279. https://doi.org/10.1075/japc.26.2.05gao

Gass, S. (1998). Apples and oranges: Or, why apples are not orange and don’t need to be a response to Firth and Wagner. The Modern Language Journal, 82(1), 83–90. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.1998.tb02597.x

Given, L. M. (Ed.) (2008). The SAGE encyclopedia of qualitative research methods. SAGE.

Grant, B. (1997). Disciplining students: The construction of student subjectivities. British Journal of Sociology of Education, 18(1), 101-114. https://doi.org/10.1080/0142569970180106

Grbich, C. (2004). New approaches in social research. SAGE.

Gu, M. M. (2010). Identities constructed in difference: English language learners in China. Journal of Pragmatics, 42(1), 139–152. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.pragma.2009.06.006

Gu, M .M., Patkin, J., & Kirkpatrick, A. (2014). The dynamic identity construction in English as lingua franca intercultural communication: A positioning perspective. System, 46(1), 131-142. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2014.07.010

Harwood, V. (2006). Diagnosing ‘disorderly’ children: A critique of behaviour disorder discourses. Routledge.

Heigham, J., & Croker, R. (2009). Qualitative research in applied linguistics: A practical introduction. Palgrave Macmillan.

Henry, A., & Goddard, A. (2015). Bicultural or hybrid? The second language identities of students on an English-mediated university program in Sweden. Journal of Language, Identity, and Education, 14(4), 255–274. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2015.1070596

Jenkins, J. (2002). A sociolinguistically based, empirically researched pronunciation syllabus for English as an International Language. Applied Linguistics, 23(1), 83-103. https://doi.org/10.1093/applin/23.1.83

Jenkins, J. (2009). English as a lingua franca: Interpretations and attitudes. World Englishes, 28(2), 200-207. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-971X.2009.01582.x

Jenkins, J. (2015). Repositioning English and multilingualism in English as a lingua franca. Englishes in Practice, 2(3), 49–85. https://content.sciendo.com/downloadpdf/journals/eip/2/3/article-p49.xml

Kachru, B. B. (1990). World Englishes and applied linguistics. World Englishes, 9(1), 3-20. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1467-971X.1990.tb00683.x

Kachru, B. B. (2011). Asian Englishes: Beyond the canon. Hong Kong University Press.

KarakaÅŸ, A. (2019). Preferred English accent and pronunciation of trainee teachers and its relation to language ideologies. PASAA: A Journal of Language Teaching and Learning, 58(1), 262-292.

Kramsch, C. (2006). The multilingual subject. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 16(1), 97-110. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.2006.00109.x

Lauder, A. (2008). The status and function of English in Indonesia: A review of key factors. Makara, Sosial Humaniora, 12(1), 9-20. https://doi.org/10.7454/mssh.v12i1.128

Menard-Warwick, J., Heredia-Herrera, A., & Palmer, D. S. (2013). Local and global identities in an EFL internet chat exchange. The Modern Language Journal, 97(4), 965-980. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1540-4781.2013.12048.x

Mistar, J. (2005). Teaching English as a foreign language (TEFL) in Indonesia. In G. Braine (Ed.), Teaching English to the world: History, curriculum and practice, (pp. 71-84). Taylor and Francis.

Norton, B. (1997). Language, identity, and the ownership of English. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 409–429. https://doi.org/10.2307/3587831

Norton, B., (2000). Identity and language learning: Gender, ethnicity and educational change. Pearson.

Norton, B. (2006). Identity as a sociocultural construct in second language education. In K. Cadman & K. O'Regan (Eds.), TESOL in Context [Special Issue], 22-33.

Norton, B. (2013). Identity and language learning: Extending the conversation. (2nd ed.). Multilingual Matters

Norton, B., & Gao, Y. (2008). Identity, investment, and Chinese learners of English. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 18(1), 109–120. https://doi.org/10.1075/japc.18.1.07nor

O’Farrell, C. (2005). Michel Foucault. SAGE.

Oxford University. (n.d.). Oxford advanced dictionary. Retrieved January 14, 2021 from https://www.oxfordlearnersdictionaries.com

Phillipson, R. (1992). Linguistic imperialism. Oxford University Press.

Phillipson, R., & Skutnabb-Kangas, T. (2013). Linguistic imperialism and endangered languages. In T. K. Bathia & W. C. Ritchie (Eds.). The handbook of multilingualism and bilingualism (pp. 495-516). Wiley-Blackwell.

Ren, W., Chen, Y., & Lin, C.-Y. (2016). University students' perceptions of ELF in mainland China and Taiwan. System, 56, 13-27. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2015.11.004

Salinas, D., & Ayala, M. (2018). EFL student-teachers’ identity construction: A case study in Chile. HOW, 25(1), 33-49. https://doi.org/10.19183/how.25.1.380

Søreide, G. E. (2006). Narrative construction of teacher identity: positioning and negotiation. Teachers and Teaching, 12(5), 527–547. https://doi.org/10.1080/13540600600832247

Sung, C. C. M. (2013). Accent and identity: Exploring the perceptions among bilingual speakers of English as a lingua franca in Hong Kong. International Journal of Bilingual Education and Bilingualism, 17(5), 544–557. https://doi.org/10.1080/13670050.2013.837861

Sung, C. C. M. (2014a). English as a lingua franca and global identities: Perspectives from four second language learners of English in Hong Kong. Linguistics and Education, 26, 31–39. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.linged.2014.01.010

Sung, C. C. M. (2014b). Global, local or glocal? Identities of L2 learners in English as a Lingua Franca communication. Language, Culture and Curriculum, 27(1), 43-57. https://doi.org/10.1080/07908318.2014.890210

Sung, C. C. M. (2014c). Hong Kong university students’ perceptions of their identities in English as a Lingua Franca contexts: An exploratory study. Journal of Asian Pacific Communication, 24(1), 94–112. https://doi.org/10.1075/japc.24.1.06sun

Sung, C. C. M. (2015). Exploring second language speakers’ linguistic identities in ELF communication: A Hong Kong study. Journal of English as a Lingua Franca, 4(2). https://doi.org/10.1515/jelf-2015-0022

Sung, C. C. M. (2016). Does accent matter? Investigating the relationship between accent and identity in English as a lingua franca communication. System, 60, 55-65. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.system.2016.06.002

Sung, C.C.M. (2019). Investments and identities across contexts: A case study of a Hong Kong undergraduate student’s L2 learning experiences. Journal of Language, Identity & Education, 18(3), 190-203. https://doi.org/10.1080/15348458.2018.1552149

Virkkula, T., & Nikula, T. (2010). Identity construction in ELF contexts: A case study of Finnish engineering students working in Germany. International Journal of Applied Linguistics, 20(2), 251-273. https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1473-4192.2009.00248.x

Wahyudi, R. (2018a). Pengalaman studi doktoral di New Zealand: Antara idealisme akademis, tantangan, keuntungan dan dialektika keilmuan [The experiences of doctoral study in New Zealand: Between academic idealism, challenges, benefits and dialectic of sciences]. In A. Ghozi (Ed.). Mendialogkan Peradaban: Sebuah kajian interdisipliner (pp. 113-126). UIN-Maliki.

Wahyudi, R. (2018b). Situating English language teaching in Indonesia within a critical, global dialogue of theories: A case study of teaching argumentative writing and cross-cultural understanding courses [Unpublished doctoral dissertation], Victoria University of Wellington. http://hdl.handle.net/10063/7609

Walshaw, M. (2007). Working with Foucault in education. Sense.

Weedon, C. (1987). Feminist practice and poststructuralist theory. Blackwell.

Widodo, H. P. (2016). Language policy in practice: Reframing the English language curriculum in the Indonesian secondary education sector. In R. Kirkpartrick (Ed.). English language education policy in Asia (pp. 127-152). Springer.

Zacharias, N.T. (2012). EFL students’ understanding of their multilingual English identities. Electronic Journal of Foreign Language Teaching, 9(2), 233–244. https://e-flt.nus.edu.sg/wp-content/uploads/2020/09/v9n22012/zacharias.pdf

[1] Badan Standar Nasional Pendidikan (National Education Standards Agency) is an independent, professional and independent institution that has a mission to develop, monitor implementation, and evaluate the implementation of National Education Standards.