Introduction

The motivation behind this study was the need to improve a teaching approach, by implementing effective techniques to develop the learning of English as a Foreign Language (EFL), in a public, socio-economically challenged institution which faces a lack of resources and opportunities to advance students socially and academically. However, the principle factor behind the study was the desire to examine the students’ lack of interest when learning English. In my setting, it had been noticed that students showed interest to learn when realia, arts (painting and theater) and task-based learning activities were implemented in class. Because of this, the researcher decided to implement a mixed approach as an interactive process that embedded meaningful activities which challenged thinking skills.

Considering this idea, when using innovative alternatives for EFL teaching and learning, Brookes (1997) carried out a qualitative research in the United States, with 14 third graders (aged 8-10, mixed gender, chosen at random) and the data showed that through the implementation of the arts framework, English language improvement was a result. Language goals, content goals, and student’s likes were taken into account when planning the lessons. What is more, the researcher mentions that:

Students who had attention problems could learn through the arts (e.g. painting) to stay on track for unbelievable lengths of time in order to achieve realistic drawings the students automatically learned to focus, concentrate, and problem solve. With motivation at its peak, teachers witnessed peak learning of course content. (p. 15)

Brookes (1997) also highlights that:

After a year of using the Arts program, school districts began reporting a 20 percent increase in reading, writing, and math scores. I watched the same phenomenon occurs when teachers integrated music, movement (e.g theatre), visual games, journal writing, and other artistic fields of study into their lessons. (p. 17)

This was also the main reason for this research to work with two disciplines of the arts: theater and painting, in order to explore the impact upon fifth graders’ communication and its role towards generating a positive EFL learning environment. The objective was to meaningfully engage students in the process of learning English by using activities that motivate and challenge them in order to develop a specific task outcome.

Integrating Arts in the EFL setting

Theater and Painting

One of the vital conditions of learning a language is that students should have a genuine interest in the activities, and materials to meet the teaching dynamics of our demanding world. Thus, teachers should explore a variety of different areas that may bring out the creative part of students. Two disciplines of theater and painting within the arts were chosen as tools to teach English in a creative manner by using activities that can motivate students in the learning process and help them engage with others. Following this intent, Wright (2001) states that the arts represent, firstly, a human dimension inherent to culture and to the social environment and, secondly, a natural activity that children do and where language can be used meaningfully and playfully.

Regarding how paining was incorporated into language classes, O’Malley, Chamot, Stewner-Manzanares, Russo, and Küpper (1985) conducted a quantitative study with a group of high school students in Philadelphia. This study incorporated painting with language learning strategies with students, and afterwards, the researchers trained students to implement some cognitive strategies by reflecting upon the impact of such teaching activities. The conclusion of the study found that most students performed better in the language class using learning strategies including the use of the arts.

Similarly, Chamot (2005) conducted a project in a Spanish class implementing theater using role plays. From this study, she concluded that performing role plays when learning a language helped students to be more engaged in the learning process. This research was significant because it relied on important aspects, such as creativity and innovation. Chamot’s study was a basis for this study using theater and painting in English classes.

Furthermore, another study was carried out by Pirie (2002) who researched the use of drama (i.e., theater) to teach French. In his study, Pirie tapped into the learners’ interest in drama to teach the language. Similarly, Pirie (2002) stated: “drama activities invite students to step into the role and combine what they know (from their own lives in the ‘real’ world) with the new or the fictional framework offered by the theatre unexpected fluency may result” (p. 22).

Along these lines, White (2001) conducted a qualitative research project with a group of 25 fifth graders in a public institution in Western Australia, which incorporated the arts with English. The results showed how students improved their language ability, using the following ideas:

- High-order thinking skills and the ability to articulate ideas– through a comprehensive arts and language program studies have also shown that integrating the arts into language instruction helps improve students’ self-concept, cognitive development, critical-thinking abilities, attention and social skills.

- Writing– for example, the use of drama and drawing as strategies for rehearsing, evaluating, and revising ideas before writing begins.

- Speaking– practice is acquired as a result of students’ participation in theater and poetry programs.

- Total reading ability, reading vocabulary, and reading comprehension– increased proficiency through role-playing, improvisation, and story writing. (White, 2001, p. 3)

Many teachers in different settings have implemented the arts to teach language in order to increase their learners’ motivation and attention as well as to achieve the goals proposed in their lessons. As a result, this research was conducted in the same manner using the arts, yet it is not often to find the arts used in a public school system in Colombia.

Regarding the association between the arts and the language teaching, it is important to mention that White (2001) points out that“The connection between language and the arts is a rich one, yet this connection has traditionally been underutilized in the classroom. As vehicles for exploration, creation, and self-expression, the two disciplines [theatre and painting] have a great deal in common” (p. 3). In this manner, it can be said that the arts which include drama (theater) and the visual arts (painting) can contribute to the development of communicative skills while exposing students to a wider range of experiences.

The arts can give teachers a dynamic set of tools to use in the language classroom. Techniques or activites, such as role plays, painting, drawing, storytelling, photography, sculpture and dance, are powerful tools and significantly impact student learning through the process of conveying meaning to others and enhancing their understanding. In fact, the arts provide a vehicle for students 1) to build their own creative productions using drawings, and 2) to design theater based role plays. Through the arts, learners can also express and explore their emotions in a safe context. These features have been found to increase children’s understanding of and attention to the activities they are involved in.

Allen (2004) also believes that bringing the arts to students is a motivating and an effective strategy that should be taken into consideration in schools due to the positive results that come from this kind of instructional implementation. He states, for example, that the Woodrow Wilson Arts Integrated School, through a partnership with the New York City Opera, had professional opera performers who conducted workshops and performances of Don Pasquale in-house with third and fifth grade students. From the participation in this experience, students showed an improvement in their critical reading skills because they were required to study and memorize their lines from various scenes before the presentation. Additionally, they felt the responsibility to memorize their portions of the script, which demonstrated their sense of responsibility and increased their autonomy as they needed to arrange time outside of workshop sessions to study their lines.

To briefly conclude, the implementation of different disciplines of the arts, such as theater and painting in the language classroom, is an innovative and effective strategy that is widely put into practice in diverse contexts across a variety of countries. For this reason, it is necessary to explore the value of applying these kinds of projects in the Colombian educational system due to the successful results of the studies depicted previously.

Methodology

This qualitative study aimed to answer the question: What features emerged from the implementation of arts in the disciplines of theater and painting among fifth grade students in a Colombian EFL public school setting? According to Merriam (1998), qualitative research is “an intensive, holistic, description and analysis of a single instance, phenomenon, or social unit” (p. 9). Along the same lines, Barbour (2008) asserts that qualitative research helps researchers to gain a deep understanding of the motives behind human behavior. Wallace (2002) mentions that qualitative research is the key to describe data, which are often subjective. All three descriptions of a qualitative reserach reflect the nature of this study.

Participants and Context

The participants involved in this study were a group of seven fifth grade students in a public school. Their English level is A2, according to the levels of the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages: Learning, Teaching and Evaluation(CEFRL) and at this level, learners are able to function in routine short social situations that require the use of simple everyday language. Participants ranged in age from about 10 to 12 years old. They were three males and four females. The participants of this study had two hours of English learning per week. Students at this institution were from both rural and urban backgrounds and they faced a lack of resources at school and at home, due to the lower socioeconomic conditions where they live. This research study took place in a public school in Usme, Bogota, Colombia, whose vision is to promote among its learners: 1) an awareness of being citizens for changing the world, and 2) learners responsible for their own decisions in their social settings. The approach used to teach English was often grammar-based. Given such little class time, it was expected that students would work autonomously outside of class.

In order to collect information, a written consent form (Appendix A) was signed by thirty students and their parents in which each one accepted to participate. Although all the pedagogical activities were implemented with all thirty students, seven students were selected to collect data from and to analyze their experience to be able to better delimitate the large amount of data from the students. Participants were selected randomly, because the randomization technique ensures that all students had an equal opportunity in the study. In this sense, randomization helped to eliminate selection bias. Students’ real names were not used for confidential purposes.

Techniques

Artifacts. According to Lankshear and Knobel (2004) artifacts correspond to the physical and concrete production of what participants carry out in a context or pre- established task. Student artefacts were collected at the end of each session and then processed during the data analysis process. They were also valuable to have a better understanding of the results of this study.

Researcher’s field notes. According to Mills (2011), field notes are defined as ¨the written records of participant observers¨ (p. 11).The main purpose of this technique was to record events, thoughts, and attitudes of the participants from the researcher’s point of view (see Appendix B).

Student journals. At the end of each session, students completed a form with three questions regarding their learning and their likes and dislikes of every class. These provided valuable information about their learning process, opinions and questions about the class activities (see Appendix C).

Data Analysis

Institutional permission was sought and granted to proceed with the study.The information elicited from the techniques were triangulated with the purpose of having different perspectives on the same topic. Burns (2010) believes that this technique helps to organize multiple features that emerge from a situation that is studied, which in the end acts as a way of validating a research study. Through data analysis, it was possible to identify patterns and relationships among different concepts.

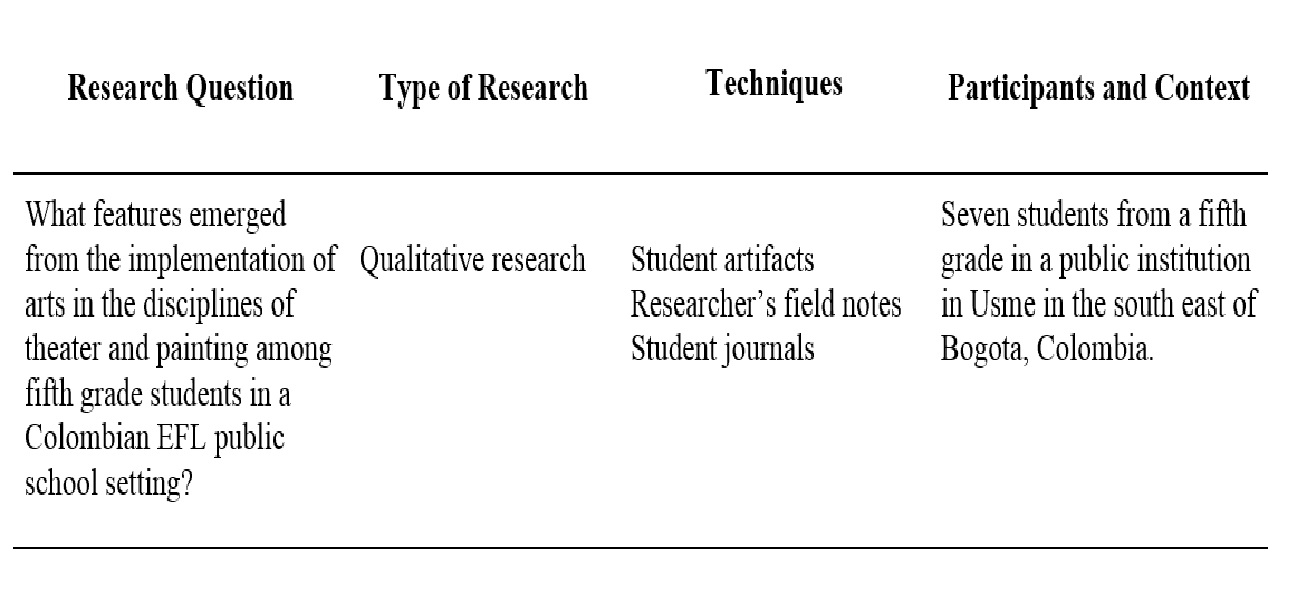

In the following chart, the research design is summarized. It contains the main question, type of research, techniques, participants, and context.

Table 1. Research design.

Regarding the data analysis, Merriam (1998) suggests three steps to follow for the process of meaning construction. The first step begins with the reading of all the data collected with their respective annotations, observations and comments. The second step is to organize those observations in separate lists or memos.The final step is to revise the techniques (student artifacts, researcher’s field notes and student journals) again to corroborate the existence of the identified groups of elements and compare those with the first list. From this revision, patterns emerged and formed the categories in the study.

Results

From the data analysis, two categories were identified: 1) Students’ enthusiasm in this study and 2) students’ responsibility through cooperative learning in this context.

Students’ enthusiasm in this study

During the development of the activities and the communicative language tasks, students followed the teacher’s instructions. Some students laughed, showing their orientation towards the language. They touched each other, and they used visual signals and verbal language to communicate. The majority of the time, the effort of the students to express themselves in English was observed. Moreover, the activities focused their attention on communication while also focusing their attention on the materials presented in class, rather than being focused on grammar and prescriptive use of English and/or being self-conscious of their spoken use of English among peers. These observations are corroborated through the following excerpts:

Through the development of theater and painting activities I found a previously unseen quality when students participated with their closest companions, interacting all the time, looking for answers and establishing patterns of enthusiasm while they developed the task outcome during the lesson. Also, I could see that students ‘saw things differently’ making references to one country and to another. The observed appreciation of seeing the world around them as something they should explore through art was exciting as students were able to express, respect their feelings. (Researcher’s field notes, Week 1, February 10)

Me gustó mucho la clase de pintura en inglés, profe, pero más cuando actuamos y nadie se burló de nuestro grupo.

[I liked the painting in the English class very much, teacher, but what I liked the most was when we had to act and no one laughed at us.]

(Participant 3, Week 2, Student journal, Feburary 17)

Participant 2, a student with mental disabilities who normally sat in his chair just writing things, today was smiling all the time. I asked him about the activity. He looked at me, then smiled and continued playing his role with other students. (Researcher’s field notes, Week 4, March 3)

The previous excerpts show how students were engaged in the activities while learning English. It is believed that the impact of the arts through theater and painting enhanced their self-confidence when students had the chance to create observable task outcomes from the activities according to their creative desires. Brown (2004), Hall and Austin (2004), and Coyle, Hood, and Marsh (2010) argue that when students are given the opportunity to make decisions about the type of work they prefer, their performance dramatically increases because it provides them a comfortable environment to accomplish a task successfully. It was noticed that group work emerged through the development of the painting activities, as students participated with observed tolerance within the group by sharing knowledge cooperatively.

Students were eager to know how much time they had left to complete the tasks in order to be able to accomplish all of them. Then, it was observed that all the students worked cooperatively and were excited about seeing the results of their tasks. This also contributed to fostering students’ attention because the painting activities engaged students all the time, making them active in the learning process. It was seen that students were highly motivated, as students participated willingly in collaborative learning. This immersed students in reflecting on their task creation by asking others their opinions. At the beginning, students began with facts and ideas and then, they moved on to applications, instead of being distant observers of questions and answers, or problems and solutions. Students became immediate practitioners giving them a rich context for learning. Students were able to experiment with and develop higher order reasoning and problem solving, which improved their skills and attention span.

Additionally, students developed the capacity to tolerate and resolve differences, coming to agreements that honored all the voices in the group. The students took care of how others were doing in the activities and in fact, these abilities are of outmost importance for students. The development of these values and skills are related to life skills outside of school and showed their construction of personalities. In that sense, interaction with the world was built using language as the linking vehicle. Another positive aspect was to see how students cultivated teamwork and community building, while participating in tasks assigned in class. These activities increased leadership skills, which are genuine and valuable aspirations for students who need to succeed in every single lesson and in life tasks outside of the classroom. For the teacher, it was valuable to observe how the activities were able to catch the students’ attention and expand the class dynamic through activities that are normally in extracurricular settings.

Students’ responsibility through cooperative learning in this context

The children generally arrived to class eager to undertake the tasks. It was noticed that the training and their performance helped them gain self-confidence in organizing their ideas, as well as improving their knowledge and skills. At the same time, it was helpful to carry out out-of-class activities related to the arts because all of the students were eager to be ready for the next session. They wanted to explore by themselves what the art activities could add to the learning process. This was a unique outcome that came from this study because autonomous learning emerged in students as well as motivation. This is validated through the following excerpts:

Students brought some materials to class on their own accord. Additionally, they mentioned to me some ideas they had in order to improve the performances when they acted. This showed that students became active participants in their own learning process. (Researcher’s field notes, Week 3, February 24)

During the analysis of the information, it was possible to find out that motivation promoted active learning throughout the expansion of previous knowledge when students wanted to do more tasks than the ones in regular classes. In general, this was because students connected the activities to enjoyment, challenge and success in their active participation in class dynamics. As an example, Participant 1 stated:

Profe, yo quiero hacer una obra maestra de pintura para el salón la próxima clase, mis papás me ayudan ¿puedo? Pero me ayudas con la descripción en inglés ¿sí?

[Teacher, for the following class, I want to make a work of art, a painting for the classroom? My parents will help me do it, but can you please help me out with the description of it in English? Will you?]

(Participant 1, Week 4, Student journal, March 3)

The following picture is an example of an artifact from Participant 1.

.jpg)

Figure 1. Artifact of Participant 1 (week 6, March 10).

Allen (2004) states that through the use of theater activities and role plays, group work emerges in the classroom and facilitates group interaction where group processes are taught or reviewed for effective group work. From the data analysis, I believe that cooperative learning is a key element in group dynamics. where students worked using arts in their English class.

Moreover, the emergence of cooperative learning highlights the influence on children’s positive attitudes. Coyle, Hood, and Marsh (2010) state “Cooperative learning increases student motivation by providing peer support. As part of a learning team, students can achieve success by working well with others” (p. 27). In addition, Pirie (2002) points out that cooperative learning creates a situation in which the group members can achieve their goals if the group is connected and responsible for every single task assigned within a group. The following excerpts illustrate this dynamic.

Me gusta la clase de inglés porque todos mis amigos me quieren y hacemos todo juntos.

[I like the English class because all my friends love me and we do everything together.]

(Participant 3, Week 7, Student journal, March 17)

Me gusta jugar futbol y baloncesto, también la clase de inglés porque las actividades con mis compañeros me divierten y se acaba rápido la clase.

[I like playing football and basketball, as well as the English class because I enjoy the activities I do with my teammates a lot. Time flies in the English class.]

(Participant 3, Week 7, Student journal, March 17)

Today a group of students who did not participate in regular classes were involved in class and one of his classmates was assigned different responsibilities and surprisingly they agreed to work together. All the members of the group in general were focused on the others’ opinions and advice. (Researcher’s field notes, Week 9, March 31)

The above examples show various processes in terms of understanding the construction of a positive environment in an EFL classroom. The data reveals that the students were particularly accepting of each other’s thoughts, which was a result of the respect and interest other students showed in the process of working together.

Discussion

To begin with, the findings of this study demonstrate that when students felt comfortable carrying out tasks assigned in the EFL classroom, they invited others to participate in a harmonious way which led to a positive environment. Moreover, English became an important subject within the recent governmental program of Bogotá Bilingual. The English program is in a lower socio-economic region of the city and consists of only a few teaching hours per week with inadequate materials and resources. In the past, repetitive traditional teaching methods were often used and they did not tap into the interests of the students. However, this study offers some insight for the future.

One critical insight highlighted is the decisive motivation which is understood as the action students take at the moment of solving tasks and this includes individual and group work. A reflective and collaborative attitude was also needed for the learning process. In particular, it is common to find classrooms where the instruction, evaluation and assessment are the same for all learners. When students are not taught taking into consideration the interests of the individual or/and group, it is truly difficult for them to find a support system to bridge the learning gaps and to make meaningful connections to the new information acquired during the process. It is therefore complicated for them to be motivated and to actively engage in the learning process.

Another positive finding was the parents’ engagement in their children’s learning process.This was quite important for the development of positive attitudes towards learning English. For example, when students received enough support at home in completing activities out-of-class, they were able to help other participants in a respectful way, as they themselves were adequately prepared for class. Additionally, it was observed that students were resourceful and they learned from their parents how to accomplish unfamiliar school tasks at home. At the same time, those students gained more self-confidence with the extra-class activities with their parents’ support even though some parents sometimes forgot to send their reports or students did not let them know about the tasks for the next class session. As a result, further research is necessary to have more involvement of the parents as well as what they are expected to do with the tasks assigned to children for homework. Moreover, it is essential to motivate parents to participate in different ways to make this interaction even more meaningful.

Additionally, even though children received sufficent support at home when completing out-of-class activities, it was beneficial that they were also able to share the same experience inside the classroom. These students felt, therefore, more motivated to keep learning than the other students who did not belong to the target research group. As a consequence, I noticed that with this research, a positive attitude was developed and this influenced the classroom dynamics increasing the responsibility of the participants. This is a clear example of what can be replicated in the other groups. When students forgot materials needed for the painting activities, the group would decide to focus on theater activities instead as a solution. In this case, it is necessary to think about how to make students aware of how to hand in tasks on time and help them to bring the needed materials. To avoid these kinds of impediments in the future, flexibility and understanding are required by means of designing strategies and implementing more motivating elements to ensure student participation.

Conclusions

The implementation of the arts using theater and painting was an appropriate strategy to encourage students to learn and also to build positive attitudes, such as responsibility, self confidence and motivation. Building on these values made students more receptive to practice the language and also to work cooperatively in projects that required time and a high level of interest from them.

Participants were engaged in using cognitive skills, such as grouping, associating, and linking concepts through activities provided by the teacher. The students enjoyed the English class activities. They took advantage of the topics that had been taught in other areas, which reinforced their background knowledge, and showed an understanding of current topics and made positive contributions to the class. English was used as a means of communication to accomplish the tasks and to learn the language itself. In this way, students were motivated and felt comfortable while exploring new topics and enhancing their knowledge. Furthermore, parents were involved in the extension of the out-of-class activities and were a valuable help in their children’s learning process.

The students were highly motivated in the English class and they improved their understanding of the concepts taught in this environment. Group work and peer interaction allowed the children to have more opportunities to have meaningful communication. Their background knowledge was enriched from interdisciplinary areas and it helped them to make significant contributions to the group. As a result, they felt better and contributed in any way they could to achieve academic success. The children tended to be critical of their own performance.

Participants increased their self-esteem and, consequently, they progressively changed certain behavioral attitudes related to some school-life activities. Students became more responsible agents in their learning. They realized that their success depended mostly on their personal efforts. As they made almost all of their learning materials, they brought the necessary tools need with them to work in class daily. When they lacked something, they asked for help to get this item before class.

In closing, this experience enriched not only the students, the institution, and the academic community, but also the teacher-researcher who conducted the study. In this sense, it was discovered that language and arts can be linked in numerous ways and that by using our autonomy and creativity, as teachers, we can introduce some reforms to the teaching practice instead of just following the specified curriculum and textbooks. In this sense, it is hoped that the results from this study can contribute to the area of teaching EFL and to raise critical questions about the integration of the arts across diverse disciplines in the EFL curriculum.

References

Allen, R. (2004). In the front row: The arts give students a ticket to learning. Curriculum Updates (ASCD), 1–3, 6–8.

Barbour, R. (2008). Introducing qualitative research: A student guide to the craft of doing qualitative research. London: Sage.

Brown, H. D. (2004). Language assessment: Principles and classroom practices. White Plains, NY: Pearson Education.

Brookes, M. (1997). Drawing with children: a creative method for adult beginners, too. Putnam, NY: Tarcher Putnam US. 8.

Burns, A. (2010). Doing action research in English language teaching: A guide for practitioners. New York: Routledge.

Chamot, A.U. (2005). The cognitive academic language learning approach (CALLA): An update. In P.A. Richard-Amato & M.A. Snow (Eds.), Academic success for English language learners: Strategies for K-12 mainstream teachers (pp. 87-101). White Plains, NY: Longman.

Coyle, D., Hood, P., & Marsh, D. (2010). CLIL Content and Language Integrated Learning. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Haley, M. H. & Austin, T. (2004). Content-based second language teaching and learning: An interactive approach. Boston, MA: Pearson Education, Inc.

Lankshear, C. & Knobel, M. (2004). A handbook for teacher research: From design to implementation. New York: Open University Press.

Merriam, S. B. (1998) Qualitative research and case study applications in education. San Francisco: Jossey-Bass.

Mills, G. E. (2011). Action research: A guide for the teacher researcher. Boston: Pearson.

O’Malley, J. M., Chamot, A. U., Stewner-Manzanares, G., Russo, R. P., & Küpper, L. (1985). Learning strategy applications with students of English as a Second Language. TESOL Quarterly, 19(3), 557-581. doi: 10.2307/3586278

Pirie, B. (2002). Teenage boys and high school English. Portsmouth, NH: Boynton/Cook.

Wallace, J. (2002). Action research for language teachers. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

White, B. (2001). Express, create, communicate – Merging English with the arts. Proceedings from AATE/ALEA Joint National Conference 2001: Leading Literate Lives. Hobart, AUS: AATE/ALEA. Retrieved from: http://www.proceedings.com.au/aate/

Wright, A. (2001). Art and craft with children. London: Oxford University Press.