Introduction

School plays an important role as the institution where integration first occurs for child migrants (Beck, Corak & Tienda, 2012; Hamann & Zúñiga, 2011). For students who have been in schools in more than one country, integration can mean managing two (or more) education systems and languages, as well as cultures and subcultures. Transitioning to a new country, getting established in a new community and dealing with whatever family matter precipitated the move in the first place (e.g., economic difficulty, deportation, death or illness of a family member) are stressful life-events, further intensified by having to negotiate the changing language contexts of school and community.

The focus of the work presented here is on the particular challenges of elementary, middle, and high school students (ages 8-17) of Mexican heritage in Mexican public schools who have returned (or have arrived for the first time) from the US. In spite of proficiency and experience in English, transnational students (TSs) are required to take English as a Foreign Language (EFL) class with all other students of their grade level. This investigation seeks to understand how TSs experience English class in Mexican schools.

A large and growing number of Mexican families who have been living in the US are returning to Mexico. The Pew Research Center Hispanic Studies reports that “[f]rom 2009 to 2014, 1 million Mexicans and their families (including children born in the US) left the US for Mexico” (González-Barrera, 2015, p. 5). The rate of return migration in almost every municipality in Mexico increased in 2010 when compared with 2003 (CONAPO, 2012). Approximately half a million children born in the U.S. were living in Mexico during the 2010 census (Alba, 2013). As a result, the number of students currently enrolled in Mexican schools who have been partly or wholly educated in the United States is substantial and increasing.

With wide-ranging proficiency levels in English and Spanish, these students encounter linguistic challenges that teachers of English are potentially well-suited to meet. The purpose of this paper is to determine how TSs experience English class in Mexican public schools. This examination also includes the way TSs perceive the class and EFL teachers. Discussion will include how English teachers might support TSs’ learning and participation in Mexican public schooling.

This research is undergirded by the conviction that students’ perspectives and experiences have merit and that their ideas regarding their own education warrant not only the attention of researchers, but also of decision-makers in the educational systems of which they are part. Accordingly, students’ own words will be considered in answering the following research questions.

RQ1: What is the experience of English-speaking transnational students in English class in Mexican schools?

RQ2: How do transnational students perceive their learning in English class?

RQ3: What role do (and could) English class and specifically English (EFL) teachers play in the educational experience of transnational students?

Methodology

As part of a larger study in which TSs were interviewed regarding their language (English and Spanish) use, ability and school experience, students were asked to talk about their experience in English class in Mexican primary, secondary, and high schools and about being English speakers in the context of Mexican schools. Interviews were conducted in English, Spanish or some combination, according to the wish of the interviewee. All the participants had at least one year of schooling in the United States prior to moving to Puebla, Mexico where they now reside and attend public schools.

After confirming that they had an English class, TSs were prompted to respond to something like: “Tell me what English class is like for you” and/or “what do you do in English class?” I also asked them if the other students knew that they spoke English and had lived in the United States. The interviews took place during the academic year of 2010-2011 and then every summer from 2012 to 2016. In 2015, I had more time with students who were taking a workshop that my students and I were offering. (See Tacelosky, 2017 for workshop description and outcomes.) Thus, I was able to request suggestions for how school teachers and administrators could support students who were coming to Mexican schools after having been educated in the U.S. (When you came to school in Mexico what would have been helpful for you with your adaptation to Mexican school?) All interviews were recorded, transcribed and analyzed for common themes.

Participants

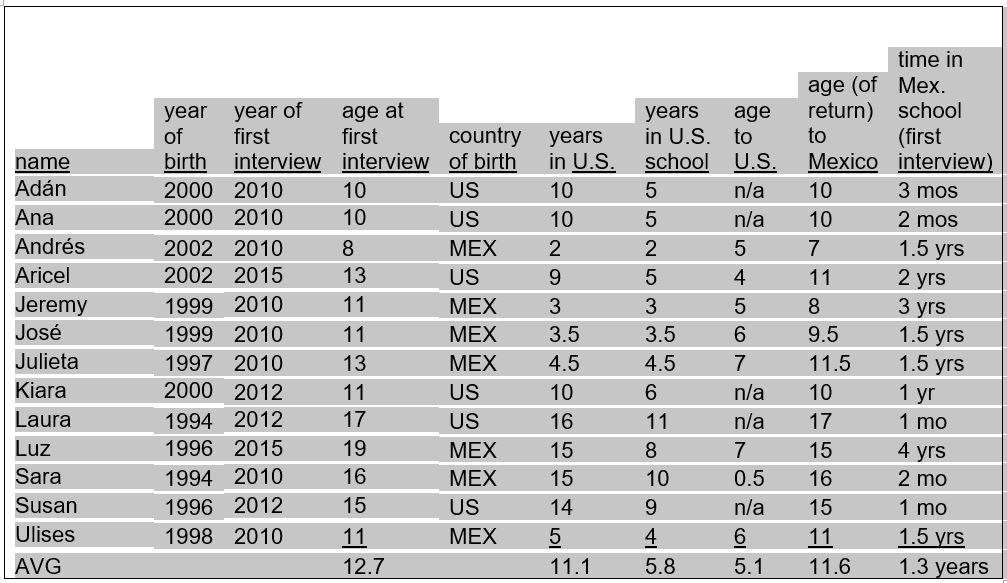

The purposeful, homogeneous sampling implemented in this study, warranted when the people under study are sought for their commonalities (as opposed to a random sample) (Palinkas et al., 2015) yielded thirty individuals. The only requirements were that students have one or more years of schooling in the United States and be enrolled in a public school in Mexico. The age range at the time of the initial interview was 8-17 (average 12 years and 8 months). Not all students were available every year and not every student had English class at the time of the interviews. Thus, the voices here are those of 13 students (see Table 1), seven of whom were interviewed on more than one occasion. The average number of years of US schooling for the participants was six (5 years and 10 months). The time (back) in Mexico at the time of the first interview ranged from two months to two years, but obviously that number changed as the years went by and participants continued to attend school. There were six girls and seven boys. Six of the participants were born in the US and seven, in Mexico. Of those born in Mexico, the average age at which they were taken to the US was five (ranging from six months to seven years). Therefore, the school experience in the US began in elementary, although three of the participants had had some primary school in Mexico. Any names used in this article are pseudonyms, often chosen by the students themselves. Students and parents signed consent forms.The study was found to be exempt from Institutional Review and of minimal risk by the Lebanon Valley College Institutional Review Board.

Table 1. Participants

Background: English Instruction in Mexico

Historically, English was not offered as a regular part of the public primary school curriculum, but rather started in secundaria (seventh, eighth and ninth grades). Spanish-English bilingual primary education was a privilege of those who could afford to attend private schools. In the public system, various governmental initiatives over the years have meant irregular offerings in English for the students I interviewed.

In 2009, the year before the field work for this project began, the SEP (Secretaría de Educación Pública/Ministry of Public Education) launched the Programa Nacional de Inglés en Educación Básica (PNIEB), or National English Program in Basic Education (NEPBE), the pilot of which was to take place in 2009-2010 (SEP, 2016). The goal of the initiative was to begin teaching English in preprimaria (nursery school and kindergarten) and to continue English-language instruction until the end of secondary school education. Although the program was intended to offer 2.5 hours per week of English language instruction (Ramírez-Romero, Sayer, & Pamplón Irigoyen, 2014), the students in the research presented here reported considerably less or none at all.

For example, Andrés said he did not have English in his primary school that year, (2012-2013) when he was in fifth grade, but that he had had it the year before (2011-2012) in the same school. Jeremy, talking about 2009-2012, indicated he had a different teacher each year and each from a different English-speaking country (e.g., Canada, US, Australia). These appear to have been native English-speakers from nearby universities doing international internships who were sent to selected schools. Those classes were held one day a week for one and a half hours. Kiara, currently in high school, confirmed that she had English class every year since she arrived in Mexico in 2012: One hour per week in sixth grade (2012-13); two hours a week in secundaria (2013-2016); and four hours a week now that she is in preparatoria (2016-2017)[1].

Results

The research questions stated above are treated in turn in this section and analyzed in the discussion section. The categories and the discussion were informed by poststructuralist and sociocultural views of language learning and identity. Thus, interpretations of culture and language as locally grounded and fixed in the individual (Schumann, 1986) are discarded. Social constructivism holds that language is not only fundamental to individual identity, but it “is the place […] where our sense of selves is constructed” (Weedon, 1997, p. 21, emphasis in original). Thus, individuals’ identities evolve as they continue to learn and develop as language users (Duff, 2007; Heath, 1983).

Additionally, relevant to this analysis is how learners are positioned into a group in terms of discursive practices. Positioning is understood as, “the discursive process whereby selves are located in conversations as observably and subjectively coherent participants in jointly produced story lines” (Davies & Harré, 1990 p. 48). Whether done by one’s self or by others, the positioning is “not necessarily intentional” (Davies & Harré, 1990 p. 48). For example, Palmer, Martínez, Mateus, & Henderson (2014) demonstrated how teachers in a dual-language program positioned students as bilinguals by affirming their abilities in two languages.

In the ESL/EFL classroom, positioning of students as experts is usually associated with those who have lengthy classroom experience. That is, they become experts at English, at least in part, through participation in the classroom experience. By contrast, the newcomer position is associated with less familiarity with English. However, in the case of the EFL classroom in Mexico, the newcomers (recent arrivals from the US) are often the ones with some level of linguistic expertise due to exposure to the language. Thus, the position of newcomer is juxtaposed with that of expert. As “[n]ewcomers to a social group [they] become socialized in the group’s culture through […] language-mediated social activity” (Morita 2000, p. 281). This puts TSs in the distinct position of not knowing the discursive practices of the local setting – the English language classroom in a Mexican school – while at the same time having expertise and experience in English. This dual positioning is revealed in TSs’ interviews as they share their mixed experience as advanced English speakers and reactions to English class.

Results of the interviews are presented here in response to each of the three research questions (RQ) articulated in the Introduction section. Then, following Kayi-Aydar (2015) the discussion section includes applying “Positioning Theory as an analytical lens” (2015, p. 137), to look at how learning is supported or threatened.

RQ1: What is the experience of English-speaking TS in English class?

Skills and Knowledge Ignored

TSs’ skills, most notably their English language abilities, are ignored. When asked what they do during English class, TSs say, “kind of do nothing” (Adán) and “I just sit and listen to the teacher” (Laura). Others report that they “sit quietly and do not say anything” (Luz) or “just copy what the teacher writes on the board” (Ulises). While it is quite possible that other students in the class may have similar reactions to language learning, the reasons that TSs provide are related to their prior experience with English.

When teachers ignore TSs’ experiences and knowledge and teach to the monolithic message of monolingualism and heterogeneity, not only do they risk insulting the intelligence of students, but also the students do not learn. Drawing on the work of others (Barbier, 2002; González, 2001; Gutierrez, 2005), Ramírez-Romero and Pamplón Irigoyen (2012) suggest that competence improves when English “is contextualized into students’ own cultural framework” (p. 48).

TSs conceal skills and experiences

More deleterious perhaps than being ignored, some TSs deliberately hide their own knowledge and experience. In other words, they pretend they do not know English and are reluctant to reveal that they have lived in the US. There are several reasons for which students may not wish for others to know: concern that others will deride them; distress that classmates will try to cheat during exams or homework; admonition from family members; and a sense of responsibility for other students’ learning. Each of these explanations is treated individually below.

Fear of ridicule. Students indicate that out of fear of derision or the desire to fit in they feign ignorance.

Sometimes I do that [pretend I don’t know English]! Because I don’t want them to say that I know everything. Like last month they were like “You know everything. You have ten on your tests.” So yeah. Sometimes I like pretend that I don’t know English. (Aricel)

Cheating. Several students indicated that if others knew about their ability, their classmates would want to cheat off of them. For example, a high-schooler who had confided in a good friend that she knew English said:

I told one of my friends “don’t tell nobody” ‘cuz if they tell, then in the exams they want me to help them. And then - I don’t know how they knew … so everybody now in the exams is like, “Help me! Help me!” Suddenly I have all the classmates [sitting] in back of me. (Julieta)

Family pressures. Another reason people may not want to share their knowledge is because of family pressures. One student told me that his mother warned him that if people found out they had lived many years in the U.S. they would think they were rich. Hence, he and his brother were advised not to speak English outside of the home. Kiara reported that in her first year of secundaria (grade seven) her classmates discovered late in the year that she had had experience in the US and was proficient in English. I asked her if she was hoping they would not find out. She indicated that her grandfather had admonished her not to boast about her abilities, “He always told me don’t like ‘no presumas eso”. And, well, that it is what I did.”

Concern for classmates’ learning. Finally, some students feel as though they are taking away from the learning experience of others. Ana, only 10 years old at the time, felt the pressure of other students watching her during class activities.

[…] everyone copied me on Simon Says. Everyone copies me, so like I try to make mistakes. So they can learn by themselves. If I do it right then everyone´s gonna copy me […] no one´s gonna learn nothing. […] I really like to participate in everything, but not with everyone copying me… I don´t feel good… (Ana)

TSs seem to recognize the value of knowing English and are genuinely concerned when classmates take actions that ultimately thwart their own learning.

RQ2: How do TS perceive their learning?

Minimal Learning and Boredom

When asked, “What did you learn/are you learning in English class?” TSs report frustration and boredom with the level of English. They relate feeling like they are in “kindergarten or first grade again” (Ulises). Several reported that it’s “the same thing year after year.” Interestingly, these are almost the same words that another researcher heard from an English teacher, “Repetition of the same [material] year after year in the school system” (Borjian, 2015). Julieta told me:

You don’t learn that much. You only learn the basic stuff like ‘Hi, how are you. How you been?’ And you always keep the same [level].

When asked what they are learning in English class, several students simply said, “Nothing.”

RQ3: What role do English teachers play in the educational experience of TSs?

TS as Teacher, Model or Helper

TSs report that sometimes they are asked to teach the class. Kiara, who is now in high school, told me that when she was 11 and in her first year of Mexican schooling ever, she was asked to teach:

Well, it was kind of weird because I was in 6th and my [English] teacher used to like to walk away, and she was like, ‘Take care of the class.’

Kiara went on to say that the teacher sometimes would ask her to stand in front of the class and “Tell them something you know.” This girl had had all of her schooling up until that point in the US and was trying desperately to adapt and fit in. She reported that being singled out like that made her feel…

…like that separated me even more from the class because they were like, ‘Oh, she know[s] English and they were treating me like sometimes different […] it was like the spotlight was on me, so that was difficult.

Years later, this girl’s mother confided in me that she had to seek psychological help for her daughter to cope that first year.

Another student said,

My teacher always told me to pronounce it – English - and almost do all the work with the kids...and that’s uncomfortable. (Aricel)

For Jeremy, interpreting from Spanish to English for a Canadian teacher who did not understand what his students were saying in Spanish, made him feel helpful. Others report not wanting to feel singled out by being asked to pronounce words or serve as a model for other students. Luz’s older sister, Violeta, who was not included in the participants’ list because she was no longer in school, mentioned that her teacher asked her for help in “how to do his class,” which made her feel “good.” Other students reacted negatively to the attention and the pressure.

Well, I first got here well it was like my first experience in Mexico and […] the teacher was like ‘Can you help me with this?’ or “Can you explain this?’ and I was like, whoa, I’m only 11 or 12 and it was kind of like a lot of pressure. (Kiara)

Sometimes the teacher or classmates ask TSs for help with classwork or homework.

Other kids bother you, asking how to say words in English […] And that’s like not that comfortable. (Aricel)

Discussion

In this section, discussion is based on the results provided above. The section that follows this one provides suggestions for English teachers.

Skills and Knowledge Ignored

TSs, like all students, deserve “cultural and linguistic validation” (Borjian & Padilla, 2010, p. 319) and to have their background, experience and funds of knowledge (Gonzalez, Moll & Amanti, 2005,) honored, not ignored. Funds of knowledge are those skills that students bring to the classroom context from their life experiences. For example, TSs are experienced international travelers. They have negotiated living in and going to school in a country whose school language is different from their home language. They have had to accomplish learning English well enough to succeed in the US and then adapt to academic Spanish. They have life and academic skills that have served them in social interactions inside and outside of school and could be an asset to the other students in the class. The challenge is to support TSs and their funds of knowledge without inadvertently threatening their sense of identity so that they will not want to suppress what they know.

TSs conceal skills and experiences

TSs know they are different from their monolingual classmates. What they perceive intuitively is supported by research. All the students in this study learned Spanish in their homes from parents or other family members. They encountered English at school in the US and began their bilingual and bicultural lives. Having two distinct domains of use – Spanish for home and English for school – does not mean that there are two separate mental systems at work. The linguistic systems of multilingual individuals are not two unrelated entities that work separately (Cook, 1994), but rather parts of a whole. Using the term translanguaging, García (2009) has demonstrated that multilinguals, rather than choosing one language or another, draw on their full linguistic repertoire to express themselves and to learn. That means that sometimes Spanish/English bilinguals use Spanglish or switch from one language to the other as means for expression and comprehension. Furthermore, use of the two languages allows students to continue to associate themselves with varying speech communities (Ellwood 2008, cited in Wang & Mansouri 2017).

The monolingual prescriptivist view, that “here we speak Spanish” for example, sometimes espoused by teachers and administrators, forces students to choose just one language and one experience, which leaves students confused and struggling. For many TSs, English is not separate from Spanish; the languages are inextricably entwined in their identity and their minds. Wang & Mansouri (2017) support a “balanced and flexible” (p. 409) approach in which all available linguistic resources are supported in the learning process. In the English language classroom, this means that students’ success requires allowing for both English and Spanish to be accessed. If teachers (and others) treat transnationals and other bilinguals as the whole people that they are and not monolinguals that are somehow lacking (Grosjean, 1989), then perhaps they would not seek to hide a part of themselves and thus have better school success.

If TSs decide to share with friends and classmates that they have experience with English, they regularly have to prove their linguistic identity. Classmates often ask them to say words in English, sometimes as a novelty, but also to demonstrate their proficiency. Several TSs reported that others did not believe them. One student told me that when she did not understand a teacher whose pronunciation was unintelligible to her (she was diplomatic, as many TSs are, about not criticizing), the teacher said, “If you are from the US why don’t you understand English?” (Luz). A direct challenge from a teacher is not only a criticism of ability, but is a threat to identity. In the language classroom, identity is in continuous flux. “[E]very time language learners speak, they are […] constantly organizing and reorganizing a sense of who they are and how they relate to the social world. They are, in other words, engaged in identity construction and negotiation” (Norton, 1997, p. 410). When students hide the fact that they know English, they are not simply masking a characteristic of their personality, they are suppressing part of who they are.

TSs as Teacher, Model or Helper

Language educators have studied language acquisition, theory and pedagogy. They/we plan lessons and prepare activities. No child or teen, or even adult, should be asked to take on the role of the teacher by “teaching the class” while the teacher leaves the room.

That said, well-meaning teachers might try to position TSs as experts, which could be a way of validating the students. While on the surface, asking TSs to read aloud, serves as a model for pronunciation or helping classmates and may be perceived as a way to honor their funds of knowledge, such a request can be counterproductive as it puts students in a position of having to perform under pressure and sometimes decide, on the spot, what to do and say.

Furthermore, when students are mostly or exclusively called on to serve as a model or expert, teachers run the risk of engaging in tokenism.Originally, the word tokenism was employed to describe the inclusion of women in traditionally all-male places of work (Kanter, 1977). However, the dangers of the practice can play out in the classroom environment. TSs are in the minority in the classroom, a fact of which they are acutely aware. When they are called on to serve as models of pronunciation or comment on what it is like to live in the United States, they are subject to “higher visibility” (p. 210) which increases pressure to perform. It also highlights “boundary heightening” (Kanter, 1977, p.221-222) or the differences between them and other students, which is the very thing they desperately want to minimize as they try to fit in and make friends. Finally, when the teacher calls on TSs to serve as experts or helpers, they may be pressured into playing a part, or in Kanter’s words “role encapsulation” (p. 230), thereby sending the message that in this class they are “helpers” or “experts.” The danger here is twofold. First, TSs might not feel prepared or willing for such roles; and second, it denies them an important, if not the central, role that they are ostensibly there for, namely learner of English. (For an alternative view of possible student roles in language classes, see Martin-Beltran’s (2013) provocative study of student positioning and participation.)

The above cautions notwithstanding, asking TSs to serve as a model or read aloud or share their story might be one way that funds of knowledge are recognized and esteemed. However, the TSs have to decide if and when they want to model or share. Some students like to be the center of attention; others prefer to take a background role. Any request of this kind has to be in consultation with the student. Thus, teachers would do well to discuss the matter privately with the TS and to be aware that their views regarding the matter may change over time.

Minimal Learning and Boredom

TSs do not perceive that they are learning in English classes. They are bored, frustrated and misunderstood. When students are not challenged in school, they are at risk of dropping out (Bridgeland, DiIulio & Morison, 2006). English, like any other language, is not simply a subject to be learned, it is a way of being in the world and knowing the world. When teachers teach “through rote memorization and translation, teaching isolated vocabulary” (Quezada, 2013, p. 9), as many of the students in this study reported, there is a disconnect between what teachers are implying and what TSs know to be true. English is not a series of irregular verbs or sentences to be copied. TSs know a lot of English speakers and none of them uses English to make lists of isolated sentences in the past tense. English is a means of communication in place where they went to school, made friends, went to the mall, etc. TSs’ identity is in some part – large or small – wrapped in English.

There is no intent here to give the impression that TSs have nothing to learn in English class. On the contrary, many of them recognize their need for more rigorous and regular engagement with English. They perceive that their skills are stagnant or slipping. Elsewhere (Tacelosky, 2013) I have reported on students’ concerns regarding forgetting or “losing” the English skills they feel they once had. TSs desire to be challenged and to learn more. In fact, when asked what would have been helpful or what would be helpful, students suggested making the class “a little bit harder” and to include “stuff that I don’t know and talk more English in all the class” (Aricel). Max, who had recently arrived to Mexico and attended the 2015 workshop, but his name is not in the participant list because he did not have an English class, told me that he would like to have a special class where all of the students who had previously studied in the US met together and “shared stories” or “read one book all together and then write […] what did we understand from that book.” While having an English class especially designed for TSs in Mexico might be a goal to work toward (as has been Spanish for Heritage speakers in the U.S.), the practical implications might be prohibitive for the moment. Thus, ideas for engaging TSs in the current English class requirement follow in the next section.

The important role of English teachers in classrooms with TSs

“Within a professional stance that understands language as a social practice, teachers need to ensure that students are provided with opportunities to go beyond what they already know and to learn to engage with unplanned and unpredictable aspects of language” (Scarino & Liddicoat, 2009).

Hard–working English teachers have many classes, many students in each class and a host of requirements to fulfill from the national curriculum. Recognizing that individual attention to a few students may be impractical, there are some simple, but potentially powerful actions and attitudes that instructors can adopt that might make a difference to the education and well-being of a TS. The suggestions that follow are not specific to a certain age, grade or level, but rather serve as general guidelines.

First, English teachers can recognize the value and experience of TSs, thus positioning them as knowledgeable experts. TSs are vulnerable. When they move to Mexico, they do not know what is going to happen to their English-speaking selves. They worry that they will lose their English. As I have already maintained, this is not simply a matter of forgetting a skill: knowing English and being an English-speaker is an essential part of who they are. In this sense, English class and English teachers have the possibility to play a central role in their lives. When teachers and other students are open to their story and do not encourage or allow name-calling and ridiculing, TSs are acknowledged for who they are, and the possibility of personal and academic success is improved.

Second, English teachers can create a classroom where students will want to share, not hide, who they are. In 21st century education much emphasis has been placed on teaching for intercultural competence (Deardorff, 2006), but in our multilingual and multicultural classrooms we must also teach with intercultural competence. That means being aware of the experiences of TSs and others (indigenous children, for example) whose life experience brings a diverse richness to the classroom. The classroom dynamic is in large part created, modeled and moderated by the teacher. Teachers can facilitate or aggravate any students’ school experience. When adaptation to school involves negotiating two language systems, language teachers can aid learning by creating a place where identity and competencies are respected, honored, and shared openly (Wang & Mansouri, 2017). Such an open and supportive environment will benefit not only the TSs, but all students in the class. Student after student in this study told me how they were made fun of. Why? Because they knew English and had lived in the US.

Additionally, English teachers would do well to proceed with caution about how to involve TSs in class, consulting students privately about their desire to serve as model and helper. One study suggested that calling on strong students was perceived by students as supportive and calling on weak students was putting undue pressure on them (Babad, 1990). Asking a student to help may be interpreted as a compliment or a threat, but in asking, we empower students. During this seven-year project, participants have gone from being children to young adults. Their views and their ability to express and reflect have changed. Even though shy, recent arrivals might not want to participate at first, in a month or a year their perspectives and wishes may change. Keep asking.

Finally, lessons for differentiated instruction can be designed with TSs in mind (Blaz, 2013). Every language classroom, indeed every classroom, has students at different levels of proficiency, motivation and ability. Consequently, activities in the classroom must provide varied learning opportunities so all can learn. One way to do this is to engage the whole class in metalinguistic awareness. For example, a teacher might ask the class, “What do you use Spanish for in your daily life?” The question may strike them as so obvious as to be laughable. But as a class, list a few: to say good morning, to play games, to buy school supplies and to text friends. Now we might ask, “What do you think people in the United States use English for?” Yes! To say good morning, to play games, to buy school supplies and to text friends. They do not memorize vocabulary lists and verb paradigms. And while it is true that the lexicon and verbal morphology will be part of what gets students to communicative competence, if they do not grasp early on that there is a bigger reason for these exercises than “a 10 on the test” they will soon lose interest.

Conclusion

This study included an examination of how students who had had U.S. schooling for an average of almost six years where English was the medium of instruction experienced English class in Mexican public schools. Their claims of frustration, boredom and discomfort in the learning environment present opportunities for the English teacher.

Not limited to the context of Mexico, the special role of the English teacher is as one who can tap into the life and language experience of students who bring to the classroom the social practices associated with the language being studied. Incorporating this knowledge and experience into the class is not a case of pandering to a few at the exclusion of the many (the rest of the class). On the contrary, it is a way to teach language that puts real meaning-making first. How many students would raise their hands if asked, “Do you know anyone who is living or has lived in the US?” With millions of immigrants in the US at any given moment, chances are the number would be high. The US is not unfamiliar to any student and is intimately known to those who have lived and attended school there. The presence of TSs in English classes is a gift, not because they can help with the class (although they may well do so), but rather because they can bring their relevant knowledge and experience to the discussion. Recognizing the strengths and varied experiences of individual students, even if they are in the minority, is beneficial to all students.

The results presented in this study, while contributing to an understanding of the experience of English-speaking transnational students in English classes in Mexican schools, have their limitations. The small sample size, while allowing for a certain depth of understanding, means limited breadth. Other students may have experiences that differ from those presented here. Furthermore, the students here were from only one region of Mexico (Puebla) and from a variety of US experiences. Extrapolating the voices and experiences of a few to other situations, must be done with caution and preferably following research that is more comprehensive. In the meantime, English-teaching professionals can begin to implement some of the suggestions made here and report on their successes and challenges in future publications.

Acknowledgements

This research was conducted with funding from the Fulbright Scholar Program and the Mexico-U.S. Commission for Educational and Cultural Exchange (COMEXUS) and from The Edward H. Arnold and Jeanne Donlevy Arnold Program for Experiential Education of Lebanon Valley College (LVC). I am very grateful to the transnational students and their families for sharing their stories with me and to my LVC students who helped with interviewing during several summers. Further, I would like to thank the librarians and at Lebanon Valley College for their timely, friendly and helpful research support. Finally, thanks to Marisela Chaplin for her overall support during the research phase and for editing assistance in the writing phase.

References

Alba, F. (2013). Mexico: The new migration narrative.Migration Policy Institute. Retrieved from https://www.migrationpolicy.org/article/mexico-new-migration-narrative

Community-based service-learning as a way to meet the linguistic needs of transnational students in Mexico. Hispania, 96(2), 328-341.

Babad, E. (1990). Calling on students: How a teacher's behavior can acquire disparate meanings in students' minds. The Journal of Classroom Interaction, 25(1/2), 1-4. Stable URL: http://www.jstor.org/stable/23870574

Barbier, C. (2002). El uso de los textos literarios en la enseñanza del francés como lengua extranjera. (Unpublished master’s dissertation). CRAPEL Universidad de Nancy 2. France.

Beck, A., Corak, M., & Tienda, M. (2012). Age at immigration and the adult attainments of child migrants to the United States.The Annals of the American Academy of Political and Social Science, 643, 134–159. Retrieved from: http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/full/10.1177/0002716212442665

Blaz, D. (2013). Differentiated instruction: A guide for foreign language teachers. New York, NY: Routledge.

Borjian, A. (2015). Learning English in Mexico: Perspectives from Mexican teachers of English. CATESOL Journal, 27(1), 163-173. Retrieved from http://www.catesoljournal.org/wp-content/uploads/2015/05/CJ27.1_borjian.pdf

Borjian, A., & Padilla, A. M. (2010). Voices from Mexico: How American teachers can meet the needs of Mexican immigrant students. The Urban Review, 42(4), 316-328. Retrieved from https://link.springer.com/article/10.1007/s11256-009-0135-0

Bridgeland, J. M., DiIulio Jr., J. J., & Morison, K. B. (2006). The silent epidemic: Perspectives of high school dropouts. A report by Civic Enterprises in association with Peter D. Hart Research associates for the Bill & Melinda Gates Foundation. Retrieved from: https://docs.gatesfoundation.org/documents/thesilentepidemic3-06final.pdf

CONAPO (Consejo Nacional de la Población). (2010). Índices de intensidad migratoria México-Estados Unidos. México: Consejo Nacional de Población. Retrieved from http://www.conapo.gob.mx/swb/CONAPO/Indices_de_intensidad_migratoria_Mexico-Estados_Unidos_2010

Cook, V. J. (1994). The metaphor of access to universal grammar. In. N. Ellis (Ed.), Implicit learning and language, (pp. 477-502). New York, NY: Cambridge University Press.

Davies, B., & Harré, R. (1990). Positioning: The discursive production of selves. Journal for the theory of social behaviour, 20(1), 43-63. Stable URL:https://doi.org/10.1111/j.1468-5914.1990.tb00174.x

Deardorff, D. K. (2006). The identification and assessment of intercultural competence as a student outcome of internationalization. Journalof Studies in International Education, 10(3), 241-266. doi: https://doi.org/10.1177/1028315306287002

Duff, P. A. (2007). Second language socialization as sociocultural theory: Insights and issues. Language Teaching, 40(4), 309-319. doi:10.1017/S0261444807004508

García, O. (2009). Education, multilingualism and translanguaging in the 21st century. In A. Mohanty, M. Panda, R. Phillipson & T. Skutnabb-Kangas (Eds.) Multilingual Education for Social Justice: Globalising the local, (pp. 128-145). New Delhi, India: Orient Blackswan (former Orient Longman).

González, L. (2001). Diagnóstico de necesidades de formación y actualización docente de los profesores de los Cursos Generales de Inglés del Departamento de Lenguas Extranjeras de la Universidad de Sonora. (Unpublished bachelor’s dissertation). Universidad de Sonora. México.

Gonzalez, N., Moll, L. C., & Amanti, C. (Eds.). (2005). Funds of knowledge: Theorizing practices in households, communities, and classrooms. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum Associates.

González-Barrera, A. (2015). More Mexicans leaving than coming to the U.S.Pew Research Center. Retrieved from http://www.pewhispanic.org/2015/11/19/more-mexicans-leaving-than-coming-to-the-u-s

Grosjean, F. (1989). Neurolinguists, beware! The bilingual is not two monolinguals in one person. Brain and Language, 36(1), 3-15. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/0093-934X(89)90048-5

Gutierrez, M. R. (2005). Perceptions and experiences of Mexican graduate learners studying in the U.S.: A basic interpretive qualitative study. (Unpublished master’s dissertation). University of Ottawa, Ontario, Canada.

Hamann, E. T., & Zúñiga, V. (2011). Schooling, national affinity(ies), and transnational students in Mexico. In S. Vandeyar (Ed.), Hyphenated selves: Immigrant identities within education contexts, (pp. 57–72). Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Rozenburg.

Heath, S. B. (1983). Ways with words: Language, life and work in communities and classrooms. Cambridge, England: Cambridge University Press.

Kanter, R. M. (1977). Men and women of the corporation. New York: Basic Books.

Kayi-Aydar, H. (2015). “He’s the star!” Positioning as a method of analysis to investigate agency and access to learning opportunities in a classroom environment. In P. Deters, X. Gao, E. R. Miller & G. Vitanova. (Eds), Theorizing and analyzing agency and second language learning: Interdisciplinary approaches. (pp. 133-153). Tonawanda, NY: Multilingual Matters.

Martin-Beltran, M. (2013). “I don’t feel as embarrassed because we’re all learning”: Discursive positioning among adolescents becoming multilingual. International Journal of Educational Research, 62, 152-161. doi: https://doi.org/10.1016/j.ijer.2013.08.005

Morita, N. (2000). Discourse socialization through oral classroom activities in a TESL graduate program. TESOL Quarterly, 34(2), 279-310. doi: https://doi.org/10.2307/3587953

Norton, B. (1997). Language, identity, and the ownership of English. TESOL Quarterly, 31(3), 409-429. Do: https://doi.org/10.2307/3587831

Secretaría de Educación Pública. (11 de julio 2017). Comunicado 184.- Presenta Nuño Mayer la Estrategia Nacional de Inglés, para que México sea bilingüe en 20 años. Gob.mx. Retrieved from: https://www.gob.mx/sep/prensa/comunicado-184-presenta-nuno-mayer-la-estrategia-nacional-de-ingles-para-que-mexico-sea-bilingue-en-20-anos

Palinkas, L. A., Horwitz, S. M., Green, C. A., Wisdom, J. P., Duan, N., & Hoagwood, K. (2015). Purposeful sampling for qualitative data collection and analysis in mixed method implementation research. Administration and Policy in Mental Health and Mental Health Services Research, 42(5), 533-544. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s10488-013-0528-y

Palmer, D. K., Martínez, R. A., Mateus, S. G., & Henderson, K. (2014). Reframing the debate on language separation: Toward a vision for translanguaging pedagogies in the dual language classroom. The Modern Language Journal, 98(3), 757-772. doi: https://doi.org/10.1111/modl.12121

Quezada, R. L. (2013). Transforming into a multilingual nation: A qualitative analysis of Mexico’s initiative to develop language teachers. MEXTESOL Journal, 37(3), 1-17. Retrieved from http://mextesol.net/journal/public/files/659c97150b834ed0a73f0b3d1d2a6617.pdf

Ramírez-Romero, J. L., Sayer, P., & Pamplón Irigoyen, E. N. (2014). English language teaching in public primary schools in Mexico: The practices and challenges of implementing a national language education program. International Journal of Qualitative Studies in Education, 27(8), 1020-1043. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/09518398.2014.924638

Ramírez-Romero, J. L., & Pamplón Irigoyen, E. N. (2012). Research in English language teaching and learning in México: Findings related to students, teachers, and teaching methods. In. R. Roux, A. Mora and N. Trejo (Eds). Research in English Language Teaching: Mexican Perspectives (pp. 43-62). Bloomington, IN: Palibrio.

Scarino, A., & Liddicoat, A. J. (2009). Teaching and learning languages: A guide. Melbourne, Australia: Curriculum Corporation.

Schumann, J. H. (1986). Research on the acculturation model for second language acquisition. Journal of Multilingual & Multicultural Development, 7(5), 379-392. doi: https://doi.org/10.1080/01434632.1986.9994254

SEP (Secretaría de Educación Pública) (2016). Evaluación de Diseño Programa Nacional de Inglés. México, SEP. Retrieved from https://www.gob.mx/cms/uploads/attachment/file/131975/S270_MOCyR_Informe_Final.pdf

Tacelosky, K. (2013). Community-based service-learning as a way to meet the linguistic needs of transnational students in Mexico. Hispania, 96(2), 328-341. Stable URL: https://www.jstor.org/stable/23608330

Tacelosky, K. (2017). Transnational students in Mexico: A summer writing workshop as a way to improve English writing skills. International Education Journal: Comparative Perspectives, 16(4), 89-101.

Wang, H., & Mansouri, B. (2017). Revisiting Code-Switching Practice in TESOL: A Critical Perspective. The Asia-Pacific Education Researcher, 26(6), 407-415. doi: https://doi.org/10.1007/s40299-017-0359-9

Weedon, C. (1987). Feminist Practice and Poststructuralist Theory. Oxford, England: Blackwell.

[1] The Secretaría of Educación in Mexico recently (July 2017) announced an ambitious initiative Estrategia Nacional de Fortalecimiento para el Aprendizaje del Inglés, which has the lofty goal of a bilingual populace in 20 years. The programs began in 2018 at the level of teacher preparation and will include six hours per week of classroom instruction and potentially six more for workshops and tutorials. (Nuño Mayer, 2017)