Introduction

Learning a second language (L2) opens avenues to new expression, cultural understanding, social interpretation, and perception of the world. Acquiring an L2 is the key to communicating effectively among diverse cultures and unifying people toward respect and tolerance in a world of misunderstandings (Morgan, 1993). Language learners seek the “holy grail” of language acquisition in hopes to bridge gaps and connect with our vast world on a human and communicative level (Yang, Crain, & Zha, 2011). Learning a second language, however, is no simple task. It is a unique process that requires dedication, tenacity, time and exposure. Educators around the globe continue to develop various methods and strategies to help second language learners acquire a foreign language effectively, providing sufficient exposure for maximum results (Nunan, 1999). Although language educators’ philosophies vary from teacher to teacher, our experiences in our pedagogy courses have examined, critiqued, borrowed from and built upon the ideals of acclaimed linguists such as Krashen (1987), Saussure (1959), Piaget (1936) and Vygotsky (1978) as well as their beliefs that L2 learning is based upon and acquired through comprehensible input, experiential learning, and, most importantly, interaction in social environments.

During a study abroad experience, total immersion in the foreign country becomes possible when an individual learns the culture and language spoken in that country simultaneously (Magnan & Back, 2006, 2007), however it is not always a realistic option for L2 learners. As practicing teachers who have organized study abroad experiences for our students, not only may students face problems of time commitment, but also a trip abroad usually comes with a variety of costs. Therefore, many students learn an L2 in a classroom setting, without having the opportunity to study abroad. Fortunately now in the 21st century, technological advancements have made it easier for people around the world to connect via a variety of mediums. In order to create a borderless classroom, international telecollaborative projects are now possible in which language learners in one location can virtually connect with parallel language learners in another location, anywhere in the world. Through this telecollaborative exchange, a form of collaboration where students from both classes work together via online tools, researchers hope to reveal the ways in which L2 learners participate and negotiate meaning in asynchronous and synchronous activities. An explanation of asynchronous and synchronous activities will be provided in the literature review.

Literature Review

With ever-expanding access to technology, simply through the click of a button, the student learning environment has expanded (Bohinski, 2014). Changes in approaches to teaching and learning an L2 have resulted in great part from this rapid development of technological advances that quickly replace existing technologies.

These types of internet-based collaborations provide authentic social interactions for students via technology. Depending on the type of technology tool that is integrated into course planning, students can communicate either synchronously or asynchronously with partners from around the world. In synchronous communication, students are virtually connecting in real-time (for example, live online chat and video conferencing) while in asynchronous communication, students are not communicating in real-time (for example, blogging and email) (Healey, 2016; Helm & Guth, 2010).

Through this virtual communication, Kern, Ware, and Warschauer (2004) state that online language learning accomplishes three main goals for a learner. First, the emphasis of the learning is placed on culture. Second, context is broadened from the local setting of the classroom, allowing for broad discussion on any subtopics that may arise from conversation. Lastly, inquiry is encouraged for communicative purposes, which in turn, can promote negotiation of meaning. Through online collaboration, L2 learners have a unique platform for linguistic maturation and cultural exchange that allow students to bridge gaps and make connections between language and culture, all while communicating to negotiate meaning and reach understanding (Helm & Guth, 2010).

As educators, it is clear that the efficacy of any language learning method is relative to the learner, as no two individual learners interpret or perceive language in the same way, and therefore associate their own unique significance to new language utterances, syntax and lexicon. In the same way, no two learners are alike when it comes to technology (Chen, 2013). Although learners have a preference with available technology tools, in a recent study (Bohinski, 2014) with sixty-six L2 learners in French and Spanish introductory courses levels I and II, almost 90% of student participants indicated that they benefited from using technology in their language course. Not only did it help reinforce course material, but it also helped hearing native speakers via authentic materials helped in the learning process. Furthermore, in telecollaborative studies (Archbold & Chami, 2015; Bohinski & Leventhal, 2015a; George & Montelongo, 2015; Hartwiger & Moore, 2015; LeSavoy, Pearlman, & Lukovitskaya, 2015; Runyan, Marchand, & Stoll, 2015; Simon & Yervasi, 2015), learners have benefitted from being able to connect with parallel learners in geographically distinct locations by being able to make deeper connections to their own coursework and to learn about culture topics from a culture other than their own. During the telecollaborative process between L2 learners, meaning from one’s existing understanding of language and culture is linked and applied to new information, or the comprehensible input, that one receives. Therefore, theL2 learner can adapt and assimilate to the new language and culture that is being experienced. Liddicoat and Scarino (2013) agree that as part of learning any additional language, the learner inevitably brings more than one language and culture to the processes of meaning-making and interpretation. That is, there are inherent intercultural processes in language learning in which meanings are made and interpreted across and between languages and cultures, in which the linguistic and cultural repertoires of each individual exist in complex interrelationships.

An L2 learner’s approach and strategy to this process of meaning making and interpretation, or negotiation of meaning, occurs naturally and out of necessity in interactions. According to interactionist theories (Gass, 1997; Long, 1996; Pica, 1991, 1994), traditionally, face-to-face (F2F) interaction, which normally includes negotiation of meaning, promotes second language learning. According to Lee (2008), negotiation of meaning generates corrective feedback and requires various approaches to reach understanding that may include checking for understanding, exchange of vocabulary and synonyms, circumlocution and assistance from other speakers in the conversation.

However, with the technologies that are available for the 21st century learner in a telecollaborative project, a variety of interaction, apart from the traditional face-to-face interaction, between L2 language learners is possible via synchronous and asynchronous environments. In efforts to be understood and to understand in the target language, L2 learners use their knowledge of their own native language and culture in tandem with the new language and culture in order to formulate a coherent, meaningful message. When the L2 speakers do not possess sufficient tools to express themselves as desired and as they would in their native tongue, in such situations, the L2 speakers must find their own methods in which they can relay their message, negotiating meaning along the way (Blake, 2000, 2005; Bower & Kawaguchi, 2011; Elola & Oskoz, 2008; Jepson, 2005; Smith 2009; O’Rourke, 2005; Wang, 2006; Yanguas, 2010; Yuksel & Inan, 2014).

According to Yanguas (2010), results that focus on oral computer-mediated communication (CMC) via Skype revealed that negotiation of meaning does occur in this context and have shown to be similar to the patterns during F2F communication. In addition, data from audio CMC showed differences in how participants negotiate meaning without the visual component. Furthermore, the findings illustrated that oral CMC “has the potential to become a very useful tool in L2 classrooms” (p. 86).

In Bower and Kawaguchi’s (2011) study, L2 learners of Japanese from Australia and L2 learners of English from Japan were grouped together in order to learn each other’s language and participated in text-based synchronous and asynchronous activities. After participants completed a text-based chat synchronous sessions, participants then were instructed to send emails post-chat regarding language corrections upon review of the chat log. Results showed that there were higher rates of corrective feedback in asynchronous text-based activities than in the synchronous ones, most likely due to the fact that 1) learners did not want to interrupt the flow of conversation during the synchronous chat and 2) participants were encouraged to provide feedback during the asynchronous post-chat emails.

Yuksel and Inan (2014) studied L2 English learners’ performance in a jigsaw activity via two types of communication: F2F and synchronous text-based computer-mediated. After completing the activities, participants were interviewed to examine the amount of noticing they did of instances of negotiation of meaning. Results indicated that participants produced more instances of negotiation of meaning during F2F interactions. The above three studies give a snapshot of the benefits of integrating synchronous and asynchronous communicative activities into an L2 classroom. Taking into consideration the role that synchronous and asynchronous computer-mediated activities can play in creating a borderless classroom and to my knowledge, the non-existence of studies examining oral CMC via Zoom, this study hopes to answer the following research questions (RQs):

RQ1: In what ways do participants negotiate meaning during synchronous Zoom and asynchronous Blackboard activities during the initial stages of a telecollaborative exchange?

RQ2: In what ways do participants stay focused on the weekly topic during synchronous Zoom and asynchronous Blackboard activities during the initial stages of a telecollaborative exchange?

RQ3: Are participation and negotiation of meaning impacted by the mode of communication, either synchronous or asynchronous, in the initial stages of a telecollaborative project?

Methods

Researchers both quantitatively and qualitatively analyzed data from the first two weeks of a telecollaborative exchange for this article. In addition to transcribing the Blackboard discussions and Zoom video sessions, all Spanish parts of both modes of communication were translated into English. After analyzing this qualitative data, research-created categories emerged from the data that were used to code the data using NVivo10. From this coding, quantitative data emerged in the form of percentages and were tallied to provide an overview of the initial weeks of the exchanges in terms of participation and negotiation of meaning.

Participants

Participants in this study participated in a Collaborative Online International Learning (COIL) exchange that partnered a Spanish 215 course (L2 learners of Spanish) at a public university in the United States (US) with a TOEFL (Test of English as a Foreign Language) Preparation course (L2 learners of English) at a private university in Mexico.

Although there were 16 partnerships created, this present article analyzes data from one particular partnership of three participants including one L2 learner of Spanish and two L2 learners of English. Since partnerships were formed before instructors knew who would be participating in the research, not all members of all partnerships consented to having their data collected. Therefore, the members of the partnership chosen for the present article were research participants and all members participated in both asynchronous and synchronous activities.

Instruments

For this telecollaboration, instructors used technologies to facilitate both asynchronous and synchronous activities. The following describes the technologies implemented.

Blackboard and Learning Management System.For the non real-time asynchronous activities, students used Blackboard, a Learning Management System (LMS), in order to create a written dialogue before and after each real-time synchronous session. Since all students were familiar with Blackboard as it was used at their individual institutions, this LMS was the likely choice. However, instructors needed to choose one institution’s LMS to use for all students so that all participants were able to take part in the same platform. Instructors decided to add Mexican students to the LMS of the US institution. Mexican students were then given login instructions to access this LMS.

Zoom.For the real-time synchronous activities, students used Zoom (http://www.zoom.us), a video conferencing tool, to meet F2F online in order to verbally discuss weekly topics. Not only did instructors like that fact that it was free, but it was a very user-friendly application for video conferencing. Videos were shared with instructors every week and the partnership student from the US institution had the responsibility to share the Zoom meeting invitation with everyone and then upload it as per instructors' directions. By making one person responsible, there was no confusion as to who was going to complete these tasks. Since the Mexican students already had to login to a different LMS as stated above, instructors thought it was fair to give the students from the US institution this responsibility.

Procedure

Prior to the semester of this COIL exchange, both course instructors worked together for several months to create activities that students would complete over the course of a six-week period via telecollaboration. Activities explored culture and university life in both their country and in the country of the partnering institution.

Ice-Breaker.Prior to the partnership and group activities beginning, students completed an ice-breaker activity so that they could get to know one another and instructors would be able to share initial information on the COIL exchange.

Weekly Activities. After the ice-breaker activity, the following five weeks of activities had three parts: pre-task, task, and post-task. Students were assigned activities that were posted on the Blackboard LMS to complete throughout the week (Monday – Friday). Since the US students were learning Spanish as an L2, their activities were posted in Spanish while the Mexican students worksheets were posted in English since they were learning English as an L2.

Pre-task. In the pre-task, students posted answers in their L2 to instructor-created general questions about the topic to trigger background information on Monday. Students then needed to react to posts from other classmates’, either in their partnership or group, on Tuesday. The pre-task set the stage for what was going to be complete during the task phase.

Task. During the task, students needed to read an authentic article(s) and/or watch authentic videos from the country of the partnering institution, which were chosen by instructors. These authentic materials gave information on the weekly topic and students were able to compare this information with the answers that they had formulated in the pre-task. After reading and/or watching these authentic materials, students met with their partner(s) on Zoom for a forty-minute video conference. During this meeting, which was due on Wednesday, students were to ask their partner(s) the instructor-created questions about the authentic materials as a springboard for more discussion. Students were also instructed that twenty minutes of the session were to be in English and the other twenty minutes in Spanish to allow for all students to practice the L2 that they were learning for twenty minutes and to be the language expert for the other half of the session (Brammerts, 2003).

Post-task. The third part of the weekly activity was the post-task. Like the pre-task, it was broken up into two parts. On Thursday, students needed to post a paragraph in their L2 about what they learned from the articles and/or videos as well as their Zoom session. Then on Friday, in order to facilitate written dialogue, students needed to react to posts from other classmates’, either in their partnership or group.

Weekly Topics.Weekly topics were chosen so that students would be able to reflect on the topic in both their country and in the country of the partnering institution. The weekly topics for Weeks 1 and 2 used for the analysis of this present article were 1) work and labor and 2) the educational system.

Data Analysis

For the analysis of the present article, the researchers’ intent was to focus on the initial stages of a telecollaborative project in order to analyze how a partnership begins and develops through participation and negotiation of meaning. After translating Spanish discussion posts into English and transcribing video sessions entirely into English, this partnership’s Blackboard Discussions and Zoom video sessions were coded using NVivo 10 for Windows, a software for analyzing and detecting patterns in qualitative data, so as to gain a more nuanced understanding of the participation and negotiation of meaning of these participants during their Week 1 and 2 activities. Using an inductive approach, all input was coded by both researchers by units of “instances” from themes that emerged from the study’s data. An instance consisted of a word, a phrase, a sentence, or group of sentences.

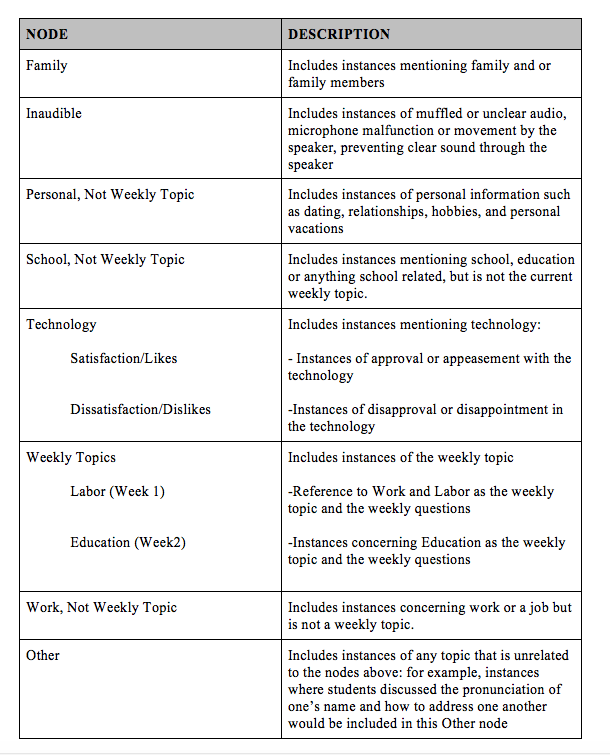

Following a careful reading of the Blackboard discussions and analysis of Zoom recordings and transcripts for the three participants, both researchers created seven principal categories in order to evaluate participation, some of which contained sub-categories, as shown in Table 1.

Table 1.Category Nodes for Evaluation of Student Participation.

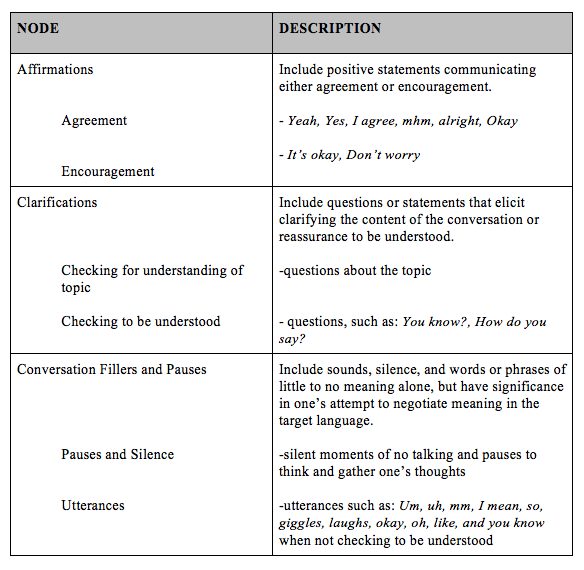

In addition, both researchers coded Blackboard discussions and Zoom video sessions in terms of negotiation of meaning. Three researcher-created categories emerged, including affirmations, clarifications, and conversation fillers and pauses, each of which had two sub-categories. All categories, along with sub-category explanations, are detailed in Table 2.

Table 2. Category Nodes for Evaluation of Negotiation of Meaning.

Using these established categories, both researchers independently coded the Blackboard discussions and Zoom video sessions for both participation and negotiation of meaning. Initial results indicated that raters had a 96.7% agreement rate (Kappa = 0.81 with p < 0.001). In order to reconcile the difference, both coders worked together to reach a 100% agreement rate.

Results

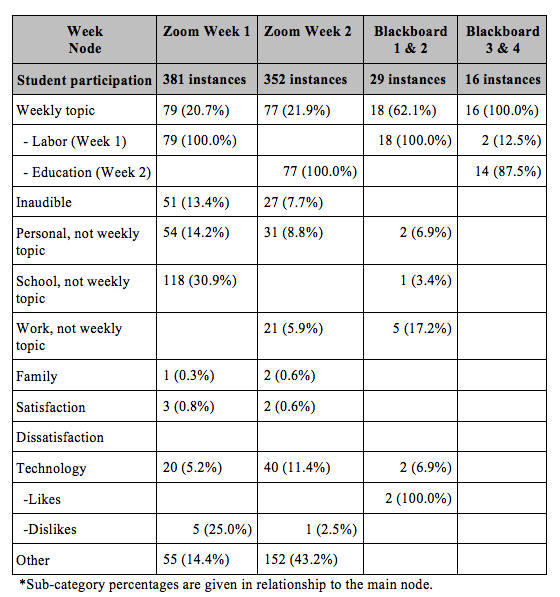

The three participants were analyzed in both asynchronous and synchronous activities so as to monitor consistencies and adaptations for both their participation in writing (asynchronous) and speaking (synchronous) and the ways in which they negotiated meaning for understanding in both mediums. Blackboard discussions 1 and 2 (pre- and post-tasks for Week 1) correspond with Zoom session 1 (task for Week 1) while Blackboard discussions 3 and 4 (pre- and post-tasks for Week 2) correspond with Zoom session 2 (task for Week 2). Within the four Blackboard discussions that correspond to two weeks of Zoom video conferencing sessions, participants’ involvement varied by week and by topic. By specifically analyzing Weeks 1 and 2 of their telecollaborative exchange, researchers were able to breakdown of the process of student participation and negotiation of meaning of this particular partnership in the initial weeks of a telecollaborative exchange. Table 3 shows an analysis of the group’s participation for the two weeks for both asynchronous and synchronous communication.

Table 3. Participation Distribution by Node*.

Among the 29 instances of participation in Blackboard discussions 1 and 2, 18 (62.1%) instances of the participants’ input related to the weekly topic of labor (Table 3). In direct relation to the weekly topic, one L2 English student commented (errors have not been corrected):

I agree that United States has better economy than México, but the economy impact in the rating of places or opportunities of work and that makes the difference of United States and México. Although in my opinion, the economy has nothing to do on the level of happiness or satisfaction. These factors are separate . . .I am really concerned about the level of unhappiness and work satisfaction and I would like to know what the solution of this problems is. . . Do you believe that a good work environment and interest in work are the solution of the problem? If it isn’t , what do you think that can solve this dilemma?

In addition, students also discussed school (3.4%), technology (6.9%), personal work (17.2%) and additional personal information (6.9%). While first becoming acquainted in the first Blackboard Discussion, the L2 Spanish participant stated (in Spanish, but given in our English translation) “I really like the activity too. Everyone is studying different subjects. For me, the audio was not clear but after listening another time, I could understand it.” Throughout the Zoom session for Week 1, there were 381 instances of participation, 79 (20.7%) of which related to the weekly topic and 118 (30.9%) pertained to school. The following exchange in English demonstrates the shift and connection among these topics in this study’s partnership.

A: Um, so, um, what, do you want to talk about? Maybe what jobs you would be looking for soon or after you finish your education? We could talk about that?

B: Uh. Do you have a job?

A: Do I have a job? I do not have a job.

B: I do, heh! I mean, I have practice. I am working at uh, a kind of uh, wood?

C: Madera?

A: Carpentry?

B: Yeah, a carpentry. And I’m working at one of those. I mean, I’m not working with wood in some, but I’m working with a design of the, of the kitchens and more rooms and etcetera.

During Week 2, Blackboard discussions 3 and 4 reflected a shift to 16 instances of participation for which 14 occurrences (87.5%) related to the weekly topic of education and 2 (12.5%) related back to the topic of labor. In Blackboard discussion 4, a L2 English participant posted two comments for the weekly topic. The first example maintains direct relevance to the weekly topic of education, and the second ties into the notion of child labor in Mexico.

Example 1: I agree with you. I think that any education system is not perfect. The United States education system has things to improve, but the important thing is that the government or the society is doing something to improve it and that is too important.

Example 2: It is difficult to say or deny to the children to stop working when they live in poverty, they need to provide money for buy things or food when the wage of the fathers are low and can't complete the basic needs of their sons. I'm not a big fan of the idea that children can work, but sometimes is necessary and if you put a rule very strict that ban children from working they wouldn't listen to you because the needs are bigger than the idea of follow the law.

Complementing the written discussions in Blackboard, students continued to discuss their weekly topic of education in the Zoom Week 2 with 352 occasions of participation. Among their input, 77 instances (21.9%) related to education, while 152 (43.2) instances were categorized as other. Participants discussed a variety of topics in English, such as the weather, wealth, and maternal leave, for approximately 18 minutes before mentioning anything in respect to education. In the following, Student A is shown discussing weather patterns of her area with another student in the partnership.

A: This winter actually hasn’t been that bad. Um, most days in January are in the negatives or they feel like they’re in the negatives, so I guess that would be around negative twenty degrees Celsius. Um, yeah, but now it’s in the, so now it’s forty, I forgot what we said that was, four degrees?

C: For us, that is too cold.

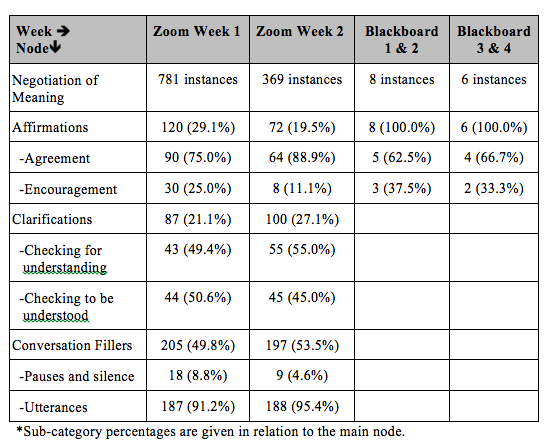

Contrary to the instances of participation, the data gathered from Zoom video session transcripts demonstrated a wider variety of instances of negotiation of meaning in oral discourse for the same two weeks. In Zoom Week 1 alone, there were 781 instances of negotiation of meaning for which 120 instances (29.1%) were affirmations, 87 instances (21.1%) were clarifications, and 209 instances (49.8%) were conversation fillers. Affirmations included agreements and other positive statements such as, “yeah,” “yes,” “mhm,” “that’s very cool,” “oh wow,” shown underlined in the quotes that follow. In English, while Student A discussed future plans to be a doctor and concerns regarding the process of applying to medical school, Student B provided some affirmations in the form of words of encouragement, as bolded below.

A: Yeah, so um it’s very competitive, and it depends on the school and sometimes, like, you may be qualified but some year you may have like, for some, that specific year, there may be a lot of very competitive students applying, and so just your luck, you’ve got a bunch of prodigies applying at the same time and you don’t get in. So, um, yeah, I may not get in at all.

B: No, you will see, you will get in . . . You’re gonna make it.

Zoom Week 2 data shows that among 369 instances of negotiation of meaning, 72 instances (19.5%) constituted of affirmations, 100 (27.1%) instances were clarifications and 197 (53.5%) instances were conversation fillers. Clarifications included several questions posed to check for understanding and to be understood in discourse. In the following exchange in English (errors have not been corrected), students asked numerous clarifying questions to discuss the weather.

A: ... How do you say wind chill?

B: A what?

A: A wind chill?

C: That’s where an idiom? Or an expression?

A: Yeah a wind chill is that. It’s basically that, it’s just um moving air that’s colder than the actual air temperature. So it’s actually like, it’s actually like, you know, say fifteen degrees Fahrenheit outside but we have a wind chill, like a cold wind, then it makes it feel like it’s negative five degrees Fahrenheit.

C: It’s cold!

With less opportunity to negotiate meaning in writing, Blackboard sessions 1 and 2 constituted solely of eight instances and Blackboard 3 and 4 were comprised of six instances, for which 100% were affirmations during both weeks. Specific affirmations used in the Blackboard sessions included “I agree”, “You’re right”, “I really like the activity too”, and “I’m happy too”. A detailed breakdown of all instances of negotiation of meaning per Blackboard discussions and Zoom sessions is shown in Table 4.

*Sub-category percentages are given in relation to the main node.

Table 4. Negotiation of Meaning Distribution by Node.

Discussion

Through this study, it has become furthermore evident that an L2 learner’s input in the target language greatly affects the outcome of their exposure and growth with the language (Kern, Ware, & Warschauer, 2004). Beyond the value of practicing one’s written language skills through online Blackboard discussions lies the invaluable experience of the one-on-one interaction through the synchronous CMC through spontaneous conversation in Zoom video sessions. Although Yanguas (2010) revealed the benefit of utilizing Skype in the L2 classroom, Zoom has not been studied as a technological tool for language learning. Like Skype, this study revealed that there are a myriad of opportunities to integrate Zoom in the L2 classroom.

The analysis of Zoom transcripts led to the detection of ways in which the students negotiated meaning in initial stages of telecollaboration, naturally giving resolution to RQ#1. Students experienced the need to use a range of strategies in order to negotiate meaning in the target language without all of the necessary skills to do so. The ultimate goal of reaching understanding was met through a series of verbal cues, involving utterances to gather one’s thoughts, questions for clarification, and statements of affirmation where L2 learners both reassured and encouraged one another throughout their discourse during synchronous CMC via Zoom.

Unlike Bower and Kawaguchi (2011), the present study revealed that participants’ instances of negotiation of meaning were higher in synchronous video meetings. This contrast in data answered RQ#3, proving that the type of communication in which students participated directly impacted their ability to negotiate meaning, with significantly more instances of such in synchronous communication. Since participants were not told to explicitly mention corrections to their partners during this study’s asynchronous activities, more than likely they focused on the content of weekly topics. However, since Zoom video sessions simulated F2F interactions, participants had the opportunity to take the conversation in various directions, expanding their exposure to new syntax and lexicon and encouraging the need to negotiate meaning (Gass, 1997; Lee, 2008; Long, 1996; Pica 1991, 1994).

Within the very first Zoom session, participants used encouragement in order to reinforce their international partner to continue their best efforts to express themselves in the target language. For example, in Spanish (our English translation is given), Participant A struggled to answer a question posed by Student C about the layout of the university, but was provided with support and encouragement from Student C.

C: Is it very big?

A: Mhm. Uh, so, uh…

C. Don’t worry. It’s okay!

The study suggests that due to the novelty of the technology for the students and the newly intimate setting within the group’s first Zoom video session, the instances of negotiation meaning were significantly high (781) as students were motivated to best understand their partners and be understood by them as well. Although the data showed fewer instances (369) of negotiation of meaning in Week 2, the percentage of clarifications constituted 27.1% of their conversation and was higher than the 21.1% during Week 1.

As new vocabulary and grammar were incorporated into conversation by native speakers, the L2 speakers demonstrated the need to ask more questions to check for understanding and clarify the understanding of the message being conveyed. Several clarifications included questions like, “no?”, “right?”, “A what?”, “Hm?”, “Is the idiom that?”, “Can you say that in Spanish again?”, and “Yeah?”. Based on the results of the study, it can be arguedthat students continued to maintain the motivation and desire to understand their peers and be understood in return.

Unlike Zoom sessions, in Blackboard discussions, students solely provided encouragement or agreement with what other students posted, but did not ask for clarification or check for understanding. Only a small number of instances for the Blackboard discussions were coded as negotiation of meaning. In spite of the fact that during asynchronous communication participants could have provided corrective feedback and negotiated meaning with their partners, participants were not encouraged to provide feedback as in Bower and Kawaguchi’s (2011) study. Participants overwhelming chose to focus on the weekly topics via the asynchronous CMC. It appears that since the Blackboard discussions did not replicate F2F communication, participants’ need to negotiate meaning was far less (14 instances) than the synchronous video sessions (1150 instances) over the initial two weeks of this telecollaborative exchange.

Similar to the results of the participants’ instances of negotiation of meaning, the participation instances over the course of the study’s two-week time period in Zoom sessions (733) were significantly higher than in the Blackboard discussions (45). During the first two weeks of the telecollaboration project, participants relied on the weekly topic during Zoom sessions as a main focus, but also as a spring-board to broader conversation topics in which they were able to share more about themselves and their experiences with their respective universities, which often carried cultural relevance and led to discussion of other topics. With various types of personal input, participants also inevitably compared and contrasted their cultures, further enhancing their intercultural competence. Beginning with the weekly topic of labor, discussion evolved into the topic of grocery chains, as shown in the following dialogue in English between participants A and C.

C: And the competition of Walmart? Nothing?

A: Not right now. I mean, there are some businesses that are better. We have businesses like Costco, which is similar, except like we have a lot of, what’s big now is grocery stores that sell in bulk.

C: Yes, we have Costco too here but just like three, or something like that. There are more Walmarts than Costco.

A: Oh there are Walmarts in Mexico too?

Participation instances both dropped in both Zoom sessions and Blackboard discussions from Week 1 to Week 2. However, participation via the asynchronous CMC decreased by almost 45%, but in Zoom sessions, participation instances dropped approximately 8%. This slight decrease in synchronous CMC suggests that interaction between speakers is more likely to occur in a simulated F2F environment.

However, the data related to asynchronous CMC showed that students’ input was more directly related to the weekly topic whereas participants did tend to deviate more from the weekly topic during synchronous CMC, shedding light on RQ#2. Participants discussed the weekly topic of labor, but reverted back to the topic of school, as they tended to fall back on the most relevant topic in their lives in the very beginning stages of getting to know one another.

In Blackboard discussions, almost 100% of all input was related to the weekly topic, however, the input varied tremendously in Zoom sessions. Participants discussed the weekly topics, but reverted back to other topics such as school and technology. This tendency to speak off the weekly topic, focusing on topics of personal important to participants, suggests that participants were being very spontaneous in their synchronous CMC and focusing more on building a relationship and rapport among their partnership in the initial stages of this study’s telecollaborative exchange. As participants were beginning to get to know one another and learn about each other’s culture, this data suggests that during synchronous CMC, participants chose to speak frequently about the topics that were common ground among everyone. In addition, according to interactionist theories (Gass, 1997; Long, 1996; Pica 1991, 1994), this interaction in this simulated F2F environment led to more negotiation of meaning. Thus, indicating that with increased participation, there is increased negotiation of meaning so that participants’ can strengthen their understanding of the messages that they are exchanging between one another.

Conclusions

This study has shown that L2 learners are capable of participating in a telecollaboration exchange and to negotiate meaning in a variety of ways to reach understanding in both asynchronous and synchronous activities. When technology connects parallel learners from geographically different locations, L2 learners are exposed to the target language and its culture in a unique way that can easily be accomplished through the click on a button. By integrating online activities, instructors can allow their L2 learners to utilize the target language in interactions with native speakers and make deeper connections to their own coursework and learn about culture topics from a culture other than their own (Archbold & Chami, 2015; Bohinski & Leventhal, 2015a; George & Montelongo, 2015; Hartwiger & Moore, 2015; LeSavoy, Pearlman, & Lukovitskaya, 2015; Runyan, Marchand, & Stoll, 2015; Simon & Yervasi, 2015).

Although traveling to distant locations is possible through various types of transportation, studying abroad for all L2 learners is not always possible. Through telecollaboration, L2 students can have a possible study abroad experience in the comfort of their own home or classroom while still receiving some of the benefits of an immersion experience. However, careful planning of a telecollaborative exchange is necessary to receive the maximum results (Bohinski & Leventhal, 2015b; Bohinski & Venegas Escobar, 2015). Also as seen with this study’s results, synchronous CMC resulted in more participation and negotiation of meaning that asynchronous CMC. Therefore, time spent on asynchronous and synchronous activities must be considered by instructors in order to maximize participation and negotiation of meaning with a native speaker.

In a world where it is possible to create a classroom without “walls” it is crucial that instructors recognize the advantages of technology and the ways in which it can connect L2 learners with the language and culture that they are studying. By utilizing a video conferencing tool such as Zoom and an online discussion tool such as Blackboard, students are given the opportunity to have intimate interactions in a small group settingas well as make a strong interpersonal connection with native speakers across the world.

Limitations and directions for future research

Since this study’s focus was based on the first two weeks of a telecollaborative exchange to examine the ways in which these students managed communicating in their partnership and how the challenges of negotiation of meaning affected their written and oral participation during the initial part of the exchange, there are limitations to generalizability. The results of this study reported only on the first two weeks of a six-week treatment period. It did not show how this partnership participated and negotiated meaning over six weeks.

Therefore, future research should be done for the entire six-week time period in order to see if the patterns that existed in the initial stages of the telecollaborative process are similar or different for the middle and end of the telecollaborative exchange.

Acknowledgements

In carrying out this study, researchers received assistance from a colleague who deserves our thanks, Salvador Venegas Escobar.

References

Archbold, M. & Chami, D. (2015). Finding common ground: Human rights and cultural difference, a student perspective. In A.S. Moore & S. Simon (Eds.), Globally networked teaching in the humanities (pp. 169–179). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Blake, R. (2000). Computer-mediated communication: A window on L2 Spanish interlanguage.

Language Learning & Technology, 4(1), 120–136. Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/vol4num1/blake/default.html

Blake, R. (2005). Bimodal CMC: The glue of language learning at a distance. CALICO Journal, 22(3), 497–511. doi: 10.1558/cj.v22i3.497-511

Bohinski, C.A. (2014). Click here for L2 learning! In Pixel (Ed.) Conference proceedings: ICT for Language Learning (7th ed.),(pp.144–148). Padova, Italy: Libreriauniversitaria.it

Bohinski, C.A. & Leventhal, Y. (2015a). Rethinking the ICC framework: Transformation and telecollaboration. Foreign Language Annals, 48(3), 521–534. doi: 10.1111/flan.12149

Bohinski, C.A. & Leventhal, Y. (2015b). Why in the world would I want to talk to someone else about my culture? The Eurocall Review, 23(1), 11–16. Retrieved from http://www.eurocall-languages.org/wordpress/wpcontent/uploads/2015/04/No23_1.pdf

Bohinski, C.A. & Venegas Escobar, S. (2015). Teamwork, technology, and online collaborations. the FLTMAG: A magazine on technology integration in the world language classroom. 13 jul, 2015. Retrieved from http://fltmag.com/teamwork-technology/

Bower, J. & Kawaguchi, S. (2011). Negotiation of meaning and corrective feedback in Japanese/English eTANDEM. Language Learning & Technology, 15(1), 41–71. Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/issues/february2011/bowerkawaguchi.pdf

Brammerts, H. (2003). Autonomous language learning in tandem: The development of a concept. In T. Lewis & L. Walker (Eds.), Autonomous language learning in tandem (pp. 27–37). Sheffield, UK: Academy Electronic Publications.

Chen, H-I. (2013). Identity practices of multilingual writers in social networking spaces. Language, Learning & Technology, 17(2), 143–170. Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/issues/february2011/bowerkawaguchi.pdf

De Saussure, F. M. (1959). Course in general linguistics. New York, NY: Philosophical Library.

Elola, I. & Oskoz, A. (2008). Blogging: Fostering intercultural competence development in foreign language and study abroad contexts. Foreign Language Annals, 41(3), 454–477. doi: 0.1111/j.1944-9720.2008.tb03307.x

Gass, S.M. (1997). Input, interaction, and the second language learner. Mahwah, NJ: Lawrence Erlbaum.

George, E. & Montelongo, I.V. (2015). Voices from the periphery: The Victoria University and University of Texas at El Paso global learning community. In A.S. Moore & S. Simon (Eds.), Globally networked teaching in the humanities (pp. 97–109). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Hartwiger, A. & Moore, A.S. (2015). Cross-cultural negotiations of human rights in literature and visual culture. In A.S. Moore & S. Simon (Eds.), Globally networked teaching in the humanities (pp. 156–168). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Healey, D. (2016). Language learning and technology: Past, present and future. In F. Farr & L. Murray (Eds.), The Routledge handbook of language learning and technology (pp. 38–55). Abingdon, UK: Routledge.

Helm, F. & Guth, S. (2010). The multifarious goals of telecollaboration 2.0: Theoretical and practical implications. In S. Guth & F. Helm (Eds.) Telecollaboration 2.0: Language, literacies, and intercultural learning in the 21st century (pp. 69–106). New York, NY: Peter Lang.

Jepson, K. (2005) Conversations--and negotiated interactions--in text and voice chat rooms. Language Learning & Technology, 9(3), 79–98. Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/vol9num3/jepson/default.html

Kern, R., Ware, P., & Warschauer, M. (2004). Crossing frontiers: New directions in online pedagogy. Annual Review of Applied Linguistics, 24, 243–260. doi: 10.1017/S0267190504000091

Krashen, S.D. (1987). Principles and practice in second language acquisition. Upper Saddle River, NJ: Prentice Hall International.

Lee, L. (2008). Focus-on-form through collaborative scaffolding in expert-to-novice online interaction. Language Learning & Technology, 12(3), 53–72. Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/vol12num3/lee.pdf

LeSavoy, B., Pearlman, A.G. & Lukovitskaya, E. (2015). Negotiating sex and gender across continents. In A.S. Moore & S. Simon (Eds.), Globally networked teaching in the humanities (pp. 124–135). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Liddicoat, A. J. & Scarino, A. (2013). Intercultural language teaching and learning. Oxford, UK: Blackwell Publishing Ltd.

Long, M. H. (1996). The role of the linguistic environment in second language acquisition. In W. C. Ritchie & T.K. Bhatia (Eds.), Handbook of second language acquisition (pp. 413–463). New York, NY: Academic Press.

Magnan, S. S. & Back, M. (2006). Requesting help in French: Developing pragmatic features during study abroad. In S. Wilkinson (ed.), Insights from study abroad for language programs (pp. 22–44). Boston, MA: Thomson Heinle.

Magnan, S. S. & Back, M. (2007). Social interaction and linguistic gain during study abroad. Foreign Language Annals 40(1), 43–61. doi: 10.1111/j.1944-9720.2007.tb02853.x

Morgan, C. (1993). Attitude change and foreign language culture learning. Language Teaching, 26(2) 63-75. doi: 10.1017/S0261444800007138

Nunan, D. (1999). Second language teaching & learning. Boston: Heinle ELT.

O’Rourke, B. (2005). Form-focused interaction in online tandem learning. CALICO Journal, 22(3), 433–466. doi: 10.1558/cj.v22i3.433-466

Piaget, J. (1936). Origins of intelligence in the child. London, UK: Routledge & Kegan Paul.

Pica, T. (1991). Classroom interaction, participation, and negotiation. System, 19(4), 437–452. doi: 10.1016/0346-251X(91)90024-J

Pica, T. (1994). Research on negotiation: What does it reveal about second language learning conditions, processes and outcomes? Language Learning, 44(3), 493–527. doi: 10.1111/j.1467-1770.1994.tb01115.x

Runyan, A.S., Marchand, M.H. & Stoll, C. (2015). Crossing borders. In A.S. Moore & S. Simon (Eds.), Globally networked teaching in the humanities (pp. 110–123). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Simon, S. & Yervasi, C. (2015). Re-envisioning diasporas in the globally connected classroom. In A.S. Moore & S. Simon (Eds.), Globally networked teaching in the humanities (pp. 136–155). New York, NY: Taylor & Francis.

Smith, B. (2009). The relationship between scrolling, negotiation, and self-initiated self-repair in an SCMC environment. CALICO Journal, 26(2), 231–245. doi: 10.1558/cj.v26i2.231-245

Vygotsky, L. S. (1978). Mind in society: The development of higher psychological processes. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

Wang, Y. (2006) Negotiation of meaning in desktop videoconferencing-supported distance language learning. ReCALL, 18(1), 122–145. doi: 10.1017/S0958344006000814

Yang, S., Crain, S.P., & Zha, H. (2011). Bridging the language gap: Topic adaptation for documents with different technicality. AISTATS, volume 15 of JMLR Proceedings, 823 –831. Retrieved from http://jmlr.csail.mit.edu/proceedings/papers/v15/yang11b/yang11b.pdf

Yanguas, Í. (2010). Oral computer-mediated interaction between L2 learners: It’s about time! Language Learning & Technology, 14(3), 72–93. Retrieved from http://llt.msu.edu/vol14num3/yanguas.pdf

Yuksel, D. & Inan, B. (2014). The effects of communication mode on negotiation of meaning and its noticing. ReCALL, 26(3), 333–354. doi: 10.1017/S0958344014000147